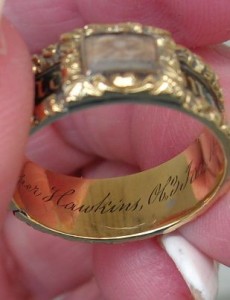

In Memory of a Beloved Child Gothic Revival Ring

Thomas Cooper Hawkins was born in 1822 and died on the third of January, 1825. This ring is a memorial to honour his memory and serves as a jewel to remind modern society about an era where love and sentimentality were part of fashion and social proprietary. From its construction, we can see elements of the Gothic Revival period within the design, particularly to the font and the edge, with the heavy floral motifs. In the centre, there is the hair dedication in a simple box weave. What this ring states from its sentiment of “In Memory of a Beloved Child” and its use of black enamel are two-fold; the ring is seemingly bespoke and it defies the conventions of the time for the use of white enamel in death.

Bespoke Sentiments

The 1820s, with its influence of the Gothic Revival as a fashionable cultural movement, led to the sentiment of the jewel becoming part of the fashion itself. The monument that the jewel created for a loved one became part of daily fashion when a person/family entered mourning. These affectations were either imposed by a society that required the presentation of mourning or the actual essence of the person that wanted to retain a memory of the loved one who passed on.

As the 1820s took back the values of earlier times, so it was with jewellery sentimentality. The statements of grief that would adorn a jewel were popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, but became part of the Neoclassical depictions in jewels by the latter 18th century. These sentiments created much of the lexicon in which the 19th century jewels would take their statements from. ‘In Memory Of’, being the most popular, was used back in the 17th century, but would become the grand statement of the 19th century; mass produced in catalogue jewels and understood as the primary statement of mourning. This ring, with its statement of ‘a Beloved Child’, requires that either the statement was created by the person who commissioned it, or that the jeweller had these rings in supply. Due to the nature of mourning rings being part of the bequeathment in a will and the high mortality rate, this ring leads towards the latter. This child had died at the age of three, in circumstances which could be understood to have been immediate, hence the parents required a mourning ring at short notice. It would not be difficult to assume that the ring was purchased and amended to accommodate the hair and inscription inside. As a method of creating mourning jewels, this is more common, rather than the ring being made specifically for the event.

The 1820s

In the 1820s, many influences upon society offered greater cultural flexibility within the social structure. The excesses of George IV and his investment in the arts bought new influences into the United Kingdom. From the death of Princess Charlotte who died in 1817, mortality was absorbed as a cross-cultural, kingdom-wide event, imposing values of the affectations of mourning on people which would resonate for the remaining 19th century. The values that were appropriated to show this in fashion led to the Gothic Revival being the identifier for grief and virtue, due to its return to religious values and simplicity that takes that pomp away from the fact of death.

The Gothic Revival period of the early 19th century is an extremely pronounced period of obvious consequences in art and architecture, but also heavily affecting in morality and cultural lifestyle. It is a period that overlapped other forms of mainstream style to eventually become the dominant visual presence, particularly in memorial jewellery and had left its mark for the greater part of the 19th century.

Firstly, we must look at this emerging style to conflict directly with the ideals of the Neoclassical period. Though the Neo-Gothic movement had begun c.1740, it took around sixty years for it to reach mainstream thought, a time when Neoclassicism was at its height.

Much of this thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

Much of the latter 19th century pieces had their origin in this Gothic Revival period, the bold styles with black enamel as well as being larger accommodated the evolution of female fashion, which heavier crinolines and cuffs, seemed to be a perfect fit. Styles didn’t automatically become larger due to the Gothic Revival influence, much of the older styles adapted Rococo acanthus designs and incorporated Gothic fonts into the lettering of the dedication in the pieces, which emerged around the c.1800-1810. By the 1820s this style was influencing brooches, rings, pendants and lockets more and more, until the 1830s when it reached its height, particularly in terms of diversity. Through the 1840s it had become the standard and into the 1850s, there was the Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys. Reflecting this upon the larger styles of female dress, pieces could be larger and lighter to wear, yet still give all the bold, gold and black enamel prominence of the pieces themselves.

Hair Sentiment

Using hair as a material and inside jewels was a sentiment that reached its heights in the 19th century

The custom of giving and receiving hairwork can be for mourning or sentimental purposes, but its singular theme is love. Rules apply in the giving of hairwork, it can be a grand statement of affection between two people and, in the past, there were rules to abide by. An unmarried girl could receive nothing from an unmarried man unless she was betrothed to him; however, a girl could give an admirer a lock of hair at his request and accept one, provided that neither was set in a jewel.

Trade of hair between family members was common, as was exchange of hair during the departure of a loved one for a period of time. Mourning pieces were often referenced in a will, with money left allocated for the chosen pieces. This could range from hairwork in rings to lockets. During the 19th century and the mass hairworking industry, inexpensive bands of woven hair (not always of the deceased), with pinchbeck fittings were a popular choice. Memorial pieces could also be commissioned by family members, in the shape of bracelets, earrings or whatever the wearer chose. This custom can be traced back to the late 16th / early 17th centuries, with notably William Shakespeare allocating mourning rings in his will (1616). There are many different reasons for the creation of hairwork jewellery and memorials, but at their inception, it is about love.

Prior to the rise of the hairworking industry and its prominence in mainstream jewellery, gifts of hair were considered tokens of affection and love between two people. Bury refers to The Relique (or The Relic) by poet John Donne (1571-1631) and its very early reference to a hair bracelet:

“When my grave is broke up againe

Some second ghest to entertaine,

(For graves have learn’d that woman-head

To be to more than one a Bed)

And he that digs it, spies

A bracelet of bright haire about the bone,

Will he not let us alone,

And thinke that there a loving couple lies”

Donne speaks in metaphysical terms about the unifying nature of spiritual love, as when he and his lover are dug up, they remain the symbol for holy and eternal love. From this, the poem is an excellent perspective on the sentimentality of hairwork at the turn of the 17th century. Wearing hair was an encompassing symbol of union and love between two people.

Donne wasn’t unique in his wearing of a hair bracelet, however, as Count de Grammont viewed several people wearing hairwork bracelets in the Court of the restored Charles II, circa 1660 1. This ties in with the rising prominence of other sentimental jewellery at that time. From love tokens, such as posy rings, to hair woven under crystal in slides, brooches, rings and other forms of jewellery, sentimental jewellery was rapidly evolving over the 17th century. Within these forms of sentimental jewellery, the use of hair became ever more prominent. Another example from 1647/8 of the popularity of hairwork within mainstream culture can be seen in Mary Varney’s letter to Sir Raplh Varney, asking to send locks of their daughter’s hair “to make bracelets? I know you could not send a more acceptable thing than every one of your sisters a bracelet”. At the time, Ralph was living in exile in France during the Protectorate. Hair tokens within families was the more common practice, but as jewels grew as a social device, so did their nature as a personal statement.

Royalty at the time also propagated the hairwork custom, exemplified by Queen Henrietta Maria (1609-69) wearing a hair bracelet as a token of affection. Factors such as these laid the groundwork for the hairworking industry that was to come. As discussed by Bury, in 1685 mourning lockets “are at least £6 in the making”. This was an extravagant price for a slide or locket of the time, leading to an increased allowance for mourning jewels in wills.

Evolution of hairwork over the 18th century was rapid and on a large scale. Jewellery changed with fashion, as the two are intrinsically linked. Smaller styles of jewellery that had grown with the 17th century began to disappear and by around 1760, and new, larger forms became the standard. Hairwork over this time was becoming more affordable and a craft which ladies could do at home (though not to the extent of the 19th century). A letter from the Duchess of Portland to Miss Catherine Collingwood, written on December 1st 1735, suggests that ladies were in the habit of working the hair, leading the goldsmiths to provide the gold settings 4. Pieces made to order became more and more popular in the first half of the 18th century, with lockets (especially in the popular heart motif) containing hair becoming increasingly common. As larger jewellery with glass replaced faceted crystal, simple weaves of hair could be placed underneath, without it being a speciality craft or as expensive.

By the 1760s, hair was reintroduced in mass produced memorial medallions and lockets (in England and on the Continent), as it was mixed in with sepia and painted on to ivory. Sepia / hair painting is a typical and very popular method from the 1760s to around 1810, with many pieces being a standard style (sometimes chosen from a hairworker’s catalogue) and tailored to the individual with the appropriate name and inscription. Chopped hair also was a common feature of memorial art on ivory (sometimes vellum), with scenes / symbolism assembled with hair and glue. Hair weaving was also in high demand, with everything from brooches to miniatures holding a compartment in which to place the woven hair. Hair weaving was becoming far more intricate, with hair being entwined with pearls and gold.

By the 19th century, the custom of hairwork had become ingrained in popular culture of the time, spanning Europe to America, and the hairworking industry hit its peak. The popularity of hairwork and its move from country to country was not a singular event, but reflects more upon society of the time. Hairworking industries along the Continent have their roots in hairwork as a folk art and female amateurs practicing the art in their home. Because of this, the popularity spread through Europe, especially prominent in France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and even across to Bohemia.

The American hairwork industry evolved in its own right, growing in prominence over the 19th century (particularly during the Civil War) and still exists in a small capacity even today. Hairwork lends itself easily to other forms of household practices, such as stitching and weaving, which makes it transcend many cultural barriers, and the sentimentality of it only adds to its necessity. As a mourning device, hairwork is a vital memorial statement within the family. Coupled with household art in the 18th to early 20th centuries, hairwork was another way to display the loved one’s hair. Samplers and hairwork memorials are prime examples of hairwork as a folk art.

Samplers vary from country to country, as do hairwork memorials, which can take the shape of flowers within wreaths, crosses and a variety of other memorial symbols. Especially in America, hair wreaths were a “popular parlor pastime like many other crafts” for women. German and Swiss hairwork memorials were often quite different from the American, as there was a greater use of depth and colour. French were more palette-worked (cut-work and sepia) and more darker, while German and Swiss hair is fairer with greater use of watercolour. German hair memorials often used two panes of glass with one being a painted background and the foreground applied hairwork. Again, regional variation within the hairwork paradigm is the prerogative of the creator or evolution within the household.

For a Child

In all, this ring is important for so many reasons, but none more so than the fact of it being for a child who died at three years old. The lack of white enamel (signifying a child/unmarried person), combined with the mourning statement and the Gothic Revival style show a progressive design for its period in time. It is a ring that resonates throughout time and continues to educate and inspire through its sentimentality today.

Further Reading:

> Gothic Revival Meets Rococo Revival in this Stunning Locket, 1834

> Holding on to a 19th Century Brooch

> Researching a Black and White Enamel 19th Century Brooch

> Mourning Band From 1770 Tells of Things to Come

> The Evolving Band in 19th Century Mourning Rings

> An 1818 Ring That Will Keep Thy Dear Remains

Courtesy: Barbara Robbins

Dedication: “In Memory of a Beloved Child / Thos Cooper Hawkins, Ob 3 Jan, 1825 AET 3 yrs.”