Mourning Rites in Victorian Britain

In 1871 James passed away and this mourning ring would have likely been one of several made for his passing. While woven human hair set into jewels was the most common practice of creating mourning jewels, many did not have human hair inside of them. This would be relegated to close friends and family, while rings such as this were produced in high volume.

By the 1870s mourning custom had reached its height, being integrated into British mourning practice for every level of society that could afford the trappings of mourning. Queen Victoria’s recommendations for the periods of mourning were widely publicised in ladies’ columns and newspapers internationally, reaching all areas of the United Kingdom. From the 1860s, the expectation for married women had changed dramatically, with a set of values being applied for the entire family unit, but with the matriarch of the family impacted the most.

- A widow… first twelve months.

- The widow’s cap must be worn for a year and a day.

- After another three months crape may be discarded.

- At the end of two years half-mourning may be worn for four or five months… the change to light grey and lavender being made gradually.

Prohibitive cost affected the desirability of the mourning industry during a time where new wealth, driven by the middle classes, challenged the established class system. Britain’s shift from a feudal styled system, to a commerce driven one, reacted against the heavy regulation of mourning custom, which effectively cut many people out of the social proprietaries that a family would need to represent themselves in mourning. It also was a statement of women to have some freedom in society, rather than be heavily regulated with rules that would apply to their social judgement. Taking several years of a lady’s life away because of the mourning regulations and the inherent cost was being frowned upon in the 1870s. Traditional land ownership was being threatened by the development of meritocracy, industrialisation, urbanisation and democratisation, shifting the focus of power from the gentry to the new wealth and the families which grew from it. Rules, while applicable for acceptable mourning practice, needed to change, as it had remained static over a period of 20 years since Victoria’s entrance into mourning.

A RESOLUTE endeavour is to be at length made to bring about a reform of our ridiculous, inconvenient, and costly mourning customs, so entirely unsuited to the habits of a time when the multiplied occupations of the living forbid the dedication of years to the dead.

Apart from the absurdity of clothing an entire family – including the servants and horses – in black for six months for a relative, not of the household, for whom the principal possibly cared little, and the domestics not at all, is the ruinous expense, and beyond the expense is the discomfort.

If it be the misfortune of a man to have many relatives, he is condemned to mourning for the greater part of his life. Take a case not uncommon. Suppose one to have six brothers and sisters who marry. There are then twelve near relatives, at the death of each of whom custom provides a “family mourning” for six months.

Then there are other twelve months for each of the parents of the heads of the family, and possibly two or three children of his own – to say nothing of all the nephews and nieces, and other casuals.

Here we have no less than sixteen years of life to be spent in black!

That is to say, one-half of the expectation of life is to be passed in discomfort and gloom, and at the cost of a small fortune, in obedience to an irrational custom of which everybody complains, but from which nobody has the courage to emaciate himself.

It has long been felt that the only means by which a more rational and convenient practice of mourning could be introduced will be by association. Many persons can do together what they could not or will not individually. Publication before the event that is the intended to depart from the bad custom when it does occur will effectively put to silence the whispers of Mrs. Grundy, which are really all that deter the many whose minds revolt against the mourning customers from at once abolishing them in practice.

A society has been established for the purpose of bringing about this most desirable reform. It proposes to accomplish that object by a few simple regulations as to mourning, which all the members will consent to observe. There will simply limit “mourning” to the heads of the family. Servants are in no case to be clothed in black, and children are to “mourn” only for their parents, brothers, or sisters. Mourning also may be indicated, as it is in the army, by crape round the arm with men, and a black sash or trimmings with women. The entrance fee is fixed at 2s only, for nothing more is required than will be sufficient to provide a fund to meet the small cost of attending its formations. Already, as we learn, great numbers have joined it, and all who approve its admirable purpose should do so at once, and especially for example’s sake should it be supported by those to whom the rare cost of “mourning” is not a consideration. The rules may be constrained on application by letter to Miss L. Whitey, Peckleston House, Hinkley, Leicestershire, who will also receive the names of members. – The Queen.

The Queen – Belfast News-letter, 1875.

A push for reformation of the mourning customs began to create a public groundswell of opinion, as can be seen in this petition to Mrs L. Whitey of Peckleston House, Hinkley, Leicestershire. She writes “apart from the absurdity of clothing an entire family – including the servants and horses – in black for six months for a relative, not of the household, for whom the principal possibly cared little, and the domestics not at all, is the ruinous expense, and beyond the expense is the discomfort.”

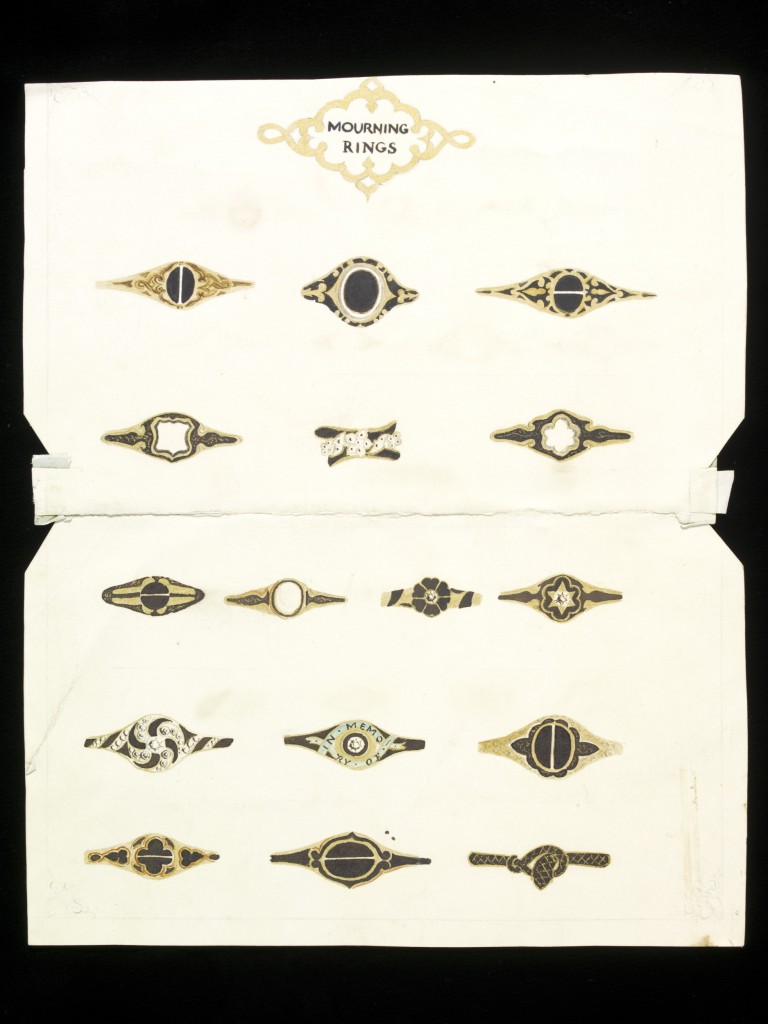

Rings that were produced for a funeral and gifted as tokens of memory were an important way of denoting the status of a family. The Hallmarking Act of 1854 allowed for the use of lower grade alloys in jewellery manufacture, which gave lower classes access to designs of higher classes in mourning jewellery. Despite this allowance, there is still a clear mark of elitism between those who could afford expensive materials in jewels and those who could not.

James’ ring is 18ct gold, elevating the status of the family during a time when 9ct and 15ct were far more common.

The design of this ring is intrinsically linked to Queen Victoria’s penchant for the serpent symbol. Serpents were made popular from the design of the engagement ring for Victoria that was given by Albert. The ring had rubies for the eyes, diamonds for the mouth, as well as a large emerald set at the centre, representing Victoria’s birthstone. Victoria and Albert were the primary influencers for Victorian symbolism. Symbols representing the hand through to the serpent were all generated by the sentimental jewels given to Victoria and they were replicated in high volume across all sentimental and mourning jewels.

Seen in the bottom right hand corner of this design study from the firm of John Brogden, the serpent, with its tail coiled around its neck (as a sentiment for eternity, much like the ouroboros, which eats its tail). Brogden was a jeweller of note, working from the 1830s to the 1880s. This design study was likely made between 1842 to 1864, where he was a partner in the firm of Watherston and Brogden (est. 1798), goldsmiths of 16 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. The second ring row from the bottom and in the middle shows the exact design heritage of this particular ring. The stylised serpent can be seen with the eyes painted, with the mouth elements open. In the ring for James, the serpent is entwined around the pearls, set in the same design. Victorian design of the latter 19th century became very economical in its elements, streamlining excess elements to become angular and simple.

Albert’s death in 1861 set Victoria in perpetual mourning and designers like Brogden were largely reinterpreting the popular styles of the 1840s and 1850s for the 1860 to 1880 period. This ring has a stylised serpent set around the 5 pearls (representing tears), an evolution of Victoria’s engagement ring and the popularity of the symbol in the second half of the 19th century.

Mourning customs may have been in decline during the 1870s, but its tradition of creating mourning products for funerals would last until the end of the generation who grew up under these customs had passed.

The ring featured in this article appears courtesy of Kalmar Antiques, who you can find on Instagram, Twitter and on their website.