Mourning Fashion & Jewels During George I & II

Between 1714 and 1760, the monarchy under George I and George II created a stable and viable mourning industry that utilised much of the talent from the Protestant influx through England and would eventually lead into the Industrial Revolution. With instability in the government, mourning fashion and jewels needed unity in identity to create a national understanding of what it was to be in mourning. Symbolism can unify a nation through identity, which jewellery and fashion can establish. Memorial and sentimental jewels were made to commemorate the birth, death or marriage of a monarch, held at their core values. Looking to the jewels of a monarch and the standardised jewels of the 18th century, one can see how Great Britain created the concept of mourning in daily life, along with the dress codes that established the stages of mourning.

Continuing from the previous article, Culture, Conflict & Mourning in the 17th & 18th Centuries, the Act of Union found England and Scotland unified the kingdoms into the Kingdom of Great Britain during the reign of Queen Anne. Whig politicians favoured succession of the crown from Anne to her nearest Protestant relative. The Tories preferred the Stuarts under hereditary right and parliament settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover and George I’s mother, as heir. Sophia’s health was waning and politicians began vying for power. Her death on the 28th of May, 1714, left George to be the direct heir. A Regency Council of members that would take power following Queen Anne’s death was revised by George and by the 1st of August, 1714, George was sworn in to be the King of Great Britain and Ireland. For the rest of his life, George was split between Germany and Great Britain.

By the 1730s, mourning ritual was bleeding through to lower levels of society in the early 18th century, which caused a reaction from higher classes.

“Women of inferior Rank, such as Tradesmen’s wives behind the Compter should make no Alteration of their Dress since it cannot arise… but from a meer Affection of the Mode at St James’s…” – Universal Spectator, 1731

Having the wealth to substantiate mourning customs in their various stages creates a line between society which cannot be crossed without upholding social standards. This acceptable presentation of oneself in society undermines the basic emotional point that mourning makes and pushes mourning into the sphere of fashion. Identity had changed a great deal since the Reformation, yet the social structure still maintained. Mourning is still a very primal reaction to death and there were those who wanted to follow mourning custom as much as possible. This involved dying their clothes through a professional silk dyer, who would dye the garment black with Indian logwood.

During his reign, George I faced rebellion through the Jacobite rebellion (“The Fifteen”), which sought to replace him with James Stuart. This rebellion was backed by disgruntled Tories and failed, leading the Whigs to gain political power for the following half century. Another Jacobite invasion through Scotland was supported by Spain in 1719, but only mustered around one thousand men, which the British defeated.

In this cameo of George I set in crystal, all the elements of the previous generation of fashionable sentimental jewellery can be seen. Crystals of the Stuart era had not disappeared with the change in monarch, but had evolved. Mourning jewellery was part of a growing industry that had begun through the rise in sentimentalism after the death of Charles I. Great access to jewels of sentimentality and artists who could produce a likeness of an individual in a portrait, or place a lock of hair under crystal or glass, meant that keepsakes were easier and cheaper to procure. What society was adapting to were figureheads of style and fashion. The upper classes generally drove what was fashionable, be it a fad, or a gem/material which had not been accessible before, or a foreign fashion that was replicated in a fashion plate or seen on a monarch. These are the things which drew attention and garnered interest in society. George I and II were more politically invested than they were for their fashionable influx. It would take future stability and colonial growth to have a monarchy that could invest in the arts to the extent of the Regency era, yet the fashions that were introduced into Britain between the years of 1714-1760 were not small.

Parliament was the key to power in Britain, with the king’s dual crowns of Hanover and and Britain showing stark contrast. On one side, he was absolute ruler, and the other, he was predominantly a figurehead. National debt and a stock market crash in 1720 created an economic crisis known as the South Sea Bubble (in relation to the South Sea Company offering to take £31 million of the nation’s debt in return for government security in stock) was managed by Sir Robert Walpole back to stability. Walpole essentially maintained power until George’s death on the 22nd of June, 1727. His son, George Augustus, was crowned on the 22nd of October, 1727.

George II was born in Hanover and was estranged from his mother, as she was denied access to her children. In 1705, George met Caroline of Ansbach under an assumed name ‘Monsieur de Busch’ at the Ansbach court and created a marriage contract with her soon after. The couple had eight children; Frederick, Anne, Amelia, Caroline, George William, William, Mary and Louisa. George was a popular figure, leading to a rift between himself and George I. He was given the title Prince of Wales in 1714, yet a confrontation between George and the Duke of Newcastle at a Christening led to George and Caroline being banished from St James’s Palace. The children remained with George I and they could only return to the palace by permission of the king, with a Regency Council being established to maintain power, rather than George Augustus, while George I was in Hanover.

Nationalism seen in sentimental jewels can be seen represented in this ring with cameo of busts of George II to the left and Caroline of Ansbach in profile to the right. The reverse of the bezel has the Garter motto in blue enamel: HONI SOIT QUI MAL Y PENSE (Evil to him who evil thinks). The Royal Collection details this ring perfectly:

“The cameos were probably executed in England before the death of Queen Caroline and the two cameos were mounted into the ring at a later date: the heavy gold band that unites them and the setting of the stones recall early 19th century Garter badges.”

The portraits in this ring originated from John Croker’s medal of 1732, although the images have been reversed suggesting the cutter was working from a printed source. The 1732 medal which shows the royal couple’s children on the reverse is thought to have been issued in response to a medal of James Francis Stuart which showed his two sons on the reverse. It is possible that these cameos were created at the same time as Croker’s work.

George I died in 1727 and George Augustus did not visit Hanover for the funeral. Sir Robert Walpole was retained through his popularity under George II, leading domestic policy. George faced family troubles with his son Fredrick, who he had left behind in Germany, while travel to Hanover made him unpopular in England. Allowance issues from the government didn’t help his popular opinion and in 1737, Caroline died.

Despite conflict with Spain and internal struggles with government, the Jacobites once more attempted to gain power. James Francis Edward Stuart’s son, Charles Edward Stuart, landed in Scotland and moved forces to the south of England. The French revoked support and Charles fled to France, leading the remaining forces to execution and ultimately crushing the Jacobite movement to restore the House of Stuart. The Seven Years’ War (1754-1763) was predominantly between France and Britain, yet involved the other great powers. This factored into much of George’s latter life and involved control of the American colonies. George passed away on October 25th, 1760 and was succeeded by his grandson, George William Frederick, who became George III.

In mourning jewellery, the memento mori style had been popular since the late 16th century. Memento mori, meaning ‘’remember death’ and remember you must die’ is a sign of mortality and final judgement. The concept of death being a factor that can happen at any moment is a message to the wearer or viewer of the symbol that life must be savoured in the moment and that final judgement awaits all. It is part an ecclesiastical statement as well as one of the intellectual and aristocratic, who could afford to adorn themselves with the memento moro symbolism. It is a statement that is ancient, with Roman depictions of memento moro joined with statements such as ‘Eat, drink, be merry, for tomorrow we die.’

Catholic domination during the middle ages utilised the memento mori symbolism greatly, instilling the values of being judged for the life you lead. Sentiments such as ‘Dye to Live’ inscribed within a memento mori ring adds to that statement, for the afterlife is the true essence of being.

Following the Restoration, Great Britain had suffered a shock to its primary values of religion and politics. In the space of three generations, the Catholic Church and the Crown had been destabilised, with the Restoration of the Crown building around a new society with new values of the ‘self’. This didn’t take away religion, but questioned the purpose of living, bringing back many of the life statements surrounding memento mori. Intellectuals and the aristocracy could wear jewellery with the memento mori symbolism and show their pursuit of a better physical existence.

With this affectation, the symbols also continued their meaning of mortality and their use in mourning jewels grew as the mourning industry grew. In the piece from c.1600, there is an early representation of the skull in an Elizabethan design. This is the nexus between the change of the symbols being decidedly mourning and previously for the statement of living.

It was the popularisation of crystal, commonly known as the ‘Stuart Crystal’ c.1603-1714 in England, during the 1680s, which popularised the look of memento mori symbolism. Seen most commonly in rings and ribbon slides (worn at the neck or cuff), oval shaped bezels with faceted crystals reflected the light in the same way as a faceted diamond would. Underneath, gold wire cypher initials being flanked by memento mori symbolism and placed on top of hair, material or vellum was a way to display identity and relationship status through a jewel on the self.

Royalty is the leading example of what mourning status should be within a certain time period. From the deaths of Charles I through to today, much of the rituals that define a certain time period are captured in the rules and regulations following the death of a monarch. George II’s death led to public, or ‘general’ mourning following his passing on the 25th of October, 1760. From the diary of Parson James Woodforde, excellent primary sources show mourning and costume in real time. From the death of George II to the period of second mourning, the creation of mourning costume is captured:

“Oct 25. N.B King George the 2nd died this morning at nine o’clock, there being an Express just arrived from London here this evening at five o’clock.” – The Diary of a Country Parson, 1758-1802, James Woodforde

Note here the passing of the king and the delay between the actual construction of the suit, which came later on November 1st. Clothes were made and not simply purchased in a store, so the orders tailors received after George’s death created a great deal of business.

“Oct. 31. Went and saw King George the third proclaimed King of England in High Street.” – The Diary of a Country Parson, 1758-1802, James Woodforde

An interesting excerpt from the diary has the coronation taking place six days after George II’s passing. Once again, the assumption that any process, from mourning to accession could be automatic and not take great effort in coordination isn’t valid. This is important to note, as the more basic items of mourning could be created (such as black drapery or an arm band), but anything more elaborate would take a period of time after death.

“Nov. 1. Had a Suit of Mourning for the King brought home this very night.” – The Diary of a Country Parson, 1758-1802, James Woodforde

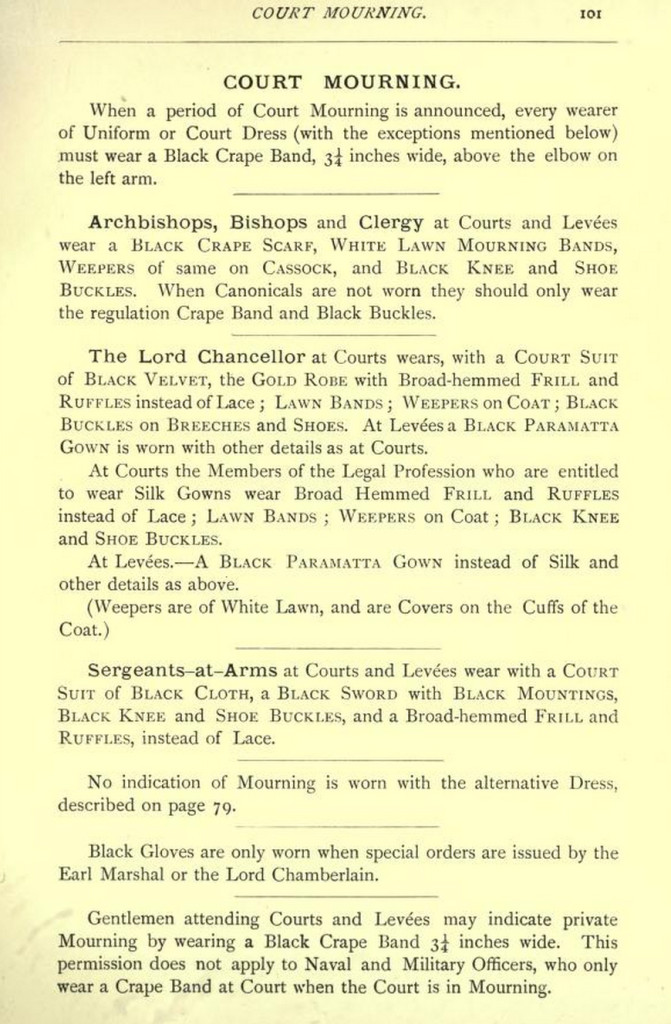

Here, the mourning suit is created and delivered in a period of seven days. One week since death, mourning costume is enabled. Consider this when even the dying of a dress was not a swift process; one must prepare for mourning or have time to prepare. First Court mourning required black woollen suits with no fashionable buttons on the pockets or the sleeves. Shirt frills were replaced with muslin or lawn cravats, while covers on the back of the cuffs of the coat (weepers) were lace. Accessories needed to follow requirements as well, asuch as black woollen stockings, gloves, crape hatbands and shammy shoes.

“Jan. 25. We went into second mourning for his late Majesty, King George the second.” – The Diary of a Country Parson, 1758-1802, James Woodforde

Three months after the death of George II and the second stage of mourning arrives. This part of mourning custom is one that is quite rigid and engrained within society. For this, Court Mourning allowed for fringed linen. Interestingly, this is not dissimilar to the Court rules of 1921.

Louis Mercer details 18th century mourning practice in ‘Le deuil: son observation dans tous les temps et dans tous les pays, comparée à son observation de nos jours’ (1877), in which he also covers mourning in antiquity and other religions. It is in the 18th century that the following insights are found in this rough translation:

“…the Court of France in the eighteenth century, as the result of an order published in 1765 under the title: Ordre chronologique des Deuils de la Court, all usual ceremonial observed in these circumstances is thoroughly described in this book:

One was the great mourning for father mother, grandfather and grandmother, husband and wife, brother and sister. They called great mourning those shared in three stages: wool, silk and Small mourning. Other shared grief do only two stages, black and white. We never draped in recent bereavement, and, whenever things not draped, women could wear diamonds, and the sword men and ball money.

The mourning of father and mother was six months. During the first three months we wore wool poplin or flush Saint-Maur,… with tapered hanging cap,… sleeved white crepe… If it was in a dress, it wearing hats… sleeves and… crepe… After six weeks we left the cap… The last six weeks were small mourning. It was black or white with brocaded gauze and similar amenities. We could then wear diamonds. Etiquette of mourning for grandfathers and grandmothers was the same, but the grief was only four months… For siblings, wool for three weeks: fifteen days silk, eight days of Small mourning. For aunts and uncles, mourning was three weeks and could wear silk… Mourning for cousins lasted fifteen days… For uncles fashionable Britain, eleven days: six black, five white. To cousins from a sibling, a week, five days in black, three in white.

Grieving husbands was a year and six weeks. During the first six months, widows wore wool Saint-Maur, tail dress turned up by a strap attached to the petticoat side, and which is brought out by the pocket; the folds of the dress were arrested in front and behind; both front joined by staples or ribbons; pagoda sleeves; the coiffiire batiste with large cuffs; a flat sleeves rank and large hem… handkerchief… a black crepe belt, stapled in front to stop the size of folds, the two loose ends to the bottom of the dress; a scarf pleated crepe from behind; the large cap black crepe; gloves, shoes… the sleeve coated flush Saint-Maur, without trim… The six other months were black silk sleeves and trim pancake white and black stones, if you wanted.

During the last six weeks, black and plain white… the choice of the widow… diamonds could be worn”

Mercer’s recording of the Order outlines a fundamentally important aspect of public mourning and how it was indoctrinated within society. Not only were the French the leaders of fashion in the time, but the rigid implementation of mourning periods filtered through all level of family. With such adherence to strict rule, it was considered the socially correct way to present the family within society and this would cost a great deal for the ordinary family of the 18th century.

A breakdown of this can be seen in the following table:

To the level of a second cousin, a family would need to reflect mourning at home. This was exploited in the 19th century, and as the industry grew. With further need to wear mourning so regularly, particularly with an average mortality rate of 37 in 1700, it’s not difficult to see how the silk and wool industries were growing by the year. Courtaulds, an English silk and crepe manufacturer, had their profit grow from £40,000 to £450,000 in the years of 1835 to 1885. Population density from the 18th century and the ability to manufacture high volumes of mourning material are all based on the need to wear such materials for social purposes.

Memento mori is the depiction of death in its most literal for. Showing the desecration of the body and the symbolism that surrounds the judgement of life after death; it truly is a statement of the wearer. Its inception bought about a new way of philosophers and the affluent to show their status of recognising that they will die, which would lead one to live life to its fullest. From the 16th century, the meaning of memento mori took these values on, representing Renaissance philosophy and the values of the Reformation.

In the rise of the mourning industry, following the 1680s, appropriation of the memento mori symbols as being representative of death and mortality for a loved one became highly popular. There was no interpretation of the symbolism, other than the nature of death itself.

This ring, but shows the elements of the perfect design for the post-1680, showing how much the memento mori design had fit into popular fashion through basic finger jewellery.

This skeletal ring dates from 1715; the absolute height of the memento mori style. It not only features the affectation of the ‘coffin’ shaped crystal, but it encapsulates the skeleton inlaid in black enamel around the band. Further to this, the element of the full skeleton inside the coffin crystal completes the sentiment. There is nowhere on the jewel that death is not represented. Its shovel and pick iconography below the skeleton’s feel around the band display a ring that was cleverly designed for its purpose.

Considering the stages of mourning with this ring, it is a memorial that latest the remainder of the life of the person whom it was commissioned for. The mourning jewel had entered the popular lexicon as being an acceptable token to be left in the will for creation upon the death of the loved one. As more money was left aside for the affectation of mourning in wills, the industry of mourning grew. A family needed to present themselves in mourning for a loved one and this required the right memento for a respectable period of mourning. In this context, it becomes about the quality of the mourning item that was produced for the family, in order for it to represent the wealth and prosperity of the family.

Developments in the cultural context of this ring show just how valuable the sentiments of mortality were. Not only were these in relation to the immediate family, but these identifiers of death remind people who see it that there is a natural outcome to dissent.

Symbols are important for holding a primary value in a culture. Without symbolism, everything can change. One common representation of death becomes a language that is understood between people. The symbol of the skeleton is so prominent in this jewel that there’s no variation for its meaning. It wants to tell you that you will die and you will decay.

Love and sentiment is important through every value of a mourning jewel. From a perspective of industry, intelligent business owners/jewellers could capitalise on these symbols which were at their height through political instability. High mortality rates and uncertainty in life choices made showing a ring with a skeleton inside and around it something which could be highly valuable and requested by the public. Mourning rings, written into wills, were swiftly becoming a popular method of donating a token of remembrance after death.

While the stages of mourning had changed to stabilise society, the mourning jewels became refined in their standardisation of death symbology. As the following Neoclassical period would show, the period of twenty years following the basic conceptualisation of a symbol, or at most a generation, was enough for it to be engrained in the popular mind of society. Once this had happened, it was up to the artisans to design the symbols that would be recognised by society and for the future generations to copy these from master moulds or primary designs styles. The biggest influences were the popular artistic and architectural styles that emerged from Europe.

Baroque influences upon these jewels began to enter through the 1680s, but became more common at the turn of the 18th century. Shapes became more rectangular in brooches, slides and bezels, with sharper facets between c.1700-1720. Memento mori symbolism was adapting to the new styles and were the main designs for mourning representation. Objects of the body or the afterlife to denote mortality were flanked with Baroque design elements through floral motifs, such as the acanthus entwining flowers. Much of this is a reaction to the dominant architectural styles seen in other physical designs, which leads the jewels to adapt to fashion.

This motif grew along with the memento mori style. It isn’t difficult to see the correlation between love above ground with that below. It is a symbol of offering a heart, the element of physical life itself, that could be worn or kept by a loved one. In the same way as a betrothal, it is a promise of love and one that still was relevant after death, for loving another goes beyond the physical realm. In this example, the style of memento mori can be seen combined with the heart. Using hair, woven over material, it only amplifies the love that the jewel offers. This can be seen in development through the Baroque period and into the Rococo, which simply added to the detail of the gold and gem embellishments.

In style, the crystal developed through the 1714-60 period, with the crystal element becoming smaller, then replaced by glass. Elements of death grew, as can be seen in the skeletal ring form 1728, but it’s simply an arranging of the different elements. Basic concepts of life and death hadn’t changed from the 17th century. Society was looking for more stability and that’s what having a greater political influence over the monarch was designed to bring. Fashion and the standards that followed only amplified the need for stability. Symbol usage grew, more areas of society could afford symbolic jewels and a government who could ordain periods of mourning held a set period of time for people to wear these symbols.

Following this, the Rococo period used the existing memento mori/Baroque styles and morphed them into a much more elegant and organic design. Bands became highly decorated and twisted into ribbon/scroll motifs, the infusion of greater floral elements was an adaptation of the dominating Baroque style and the bezels on mourning rings became smaller. It wasn’t until c.1765 and the introduction of the Neoclassical period that the greatest challenge to the memento mori style would essentially relegate it to become an anachronism.

Wearing a jewel to show that you will be judged and to live life for all its benefits is quite a grand statement during times with high mortality rates and a more feudal-based system of government, but during the 1670s-80s, there’s a strong shift to higher industry, specialised work and education. Mortality rates from the 17th century only maintained the need for understanding the fine line between life and death. In 1660, the Great Plague of London in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666 were major events that captured a moment in time for a population to maintain public mourning. The symbols of death could be appropriated for an industry that was reacting to the execution of a king and a subsequent civil war, it could pick up on the nuanced tokens of affection that became popular from this and it could produce a product that was relatively easier to produce and almost the same to sell.

As the above ring shows, the nature of the skeletal ring had become a popular enough design in mourning rings that it was enough to complement the popular crystal jewels. Symmetry of the design and the balance of the skeleton with memento mori motifs (hourglass (time flies/tempus fugit, hearts, shovel) all have the desecration of the body and body elements of love as their accepted design construction.

Basic messages of love were written inside the bands during this time, while they would appear outside the band in the later 18th century to become most popular in the early 19th century. Messages in basic writing were more difficult to do in a time that predates the dictionary, yet jewellery accommodated in different ways.

Connection between communities was advanced through the use of written language, particularly that within chapbooks. Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written in jewels, particularly inside posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content.

Society was at a point where events had overtaken the immediacy of global rule and communications that didn’t end at the limit of a village. Now, the world had opened up in ways which forced society to accept the relationships developed on a personal nature to be the truth, beyond religious or crown judgement.

In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

As the Protestant Reformation was such a reaction to the Catholic Church, the Baroque style was encouraged from the early 17th century as an emotive way of influencing and dominating art with religion. It is an imposing style, particularly in architecture, with an opulence and power that seems all pervasive, particularly when used in context of religious places of worship.

In this ring which has its origins in 1780, the memento mori motifs weren’t as common as they had been prior to 1760. The ring does not conform to its contemporary style, though it is an evolution of the previous style that had come before. Considering that barely a generation had passed between this and the previous memento mori rings, this piece shows all the elements of romanticised memento mori in a time that did not represent the decay of the body so literally.

As with all jewellery, what is presented is personal to what one had as their value system. If a religion presented one in mourning as being leaning closer to a Catholic, rather that a Protestant belief, than it was more typical for the jewel to have greater Christian allegorical designs. If, perhaps in this case, that the ring was designed for family values and much of the design comes from the attitudes of the person who had passed on, then the design overtakes fashion. What is most basic in the construction of these jewels throughout the 18th century is that death and taxes are two of life’s absolutes and lead to a good profit being made from the act of grief. As long as the requirement of presenting oneself in public with the trappings of grief when a loved one has died, there was a jewel to be made.

Combine the mortality rate in the mid 17th century to be around 40, with even childhood being difficult to survive and the message of this ring shares its honesty. Life was difficult and there were many opportunities to fight for a political ideal and get monetary rewards, which allowed for sentimental jewels to flourish. Capitalisation on these causes, as well as the various disasters, be they natural or otherwise, only played to the heart of love itself. As a population, we require the company and love of others, as well as their support. Without giving thanks to this concept in a ring or jewel, then the connectivity between societies and cultures does not lend itself to memory and learning through what has come before. If not for the generation that enabled the Protestant movement, then all that had been in the latter 17th century would not exist.

Resonating mortality for its time, this skeletal ring was at the height of its fashion and its sentiment. Surrounded by turmoil, yet reflected in love, the ring reflects several skeleton motifs and the desecration of the body. Why this was such a popular motif was the immediacy of death to the wearer and the viewer of the ring. At no stage is there any consideration for a beautiful life after death, or that the mourning is a sad occasion for opulent decoration – memento mori presents death in its basic fundamental. Remember you will die, this ring tells us.

Even from the perspective of design, the skeletal motif is not welcoming or pleasant in its demeanour, its visage is grim and it wards the wearer to uphold the ideals of life as it exists and live life to its fullest.

From what one can see from how jewellery, royalty, politics and simple fashion had in the way of keeping status and order together, the primary element of mourning for its time combined death and life. Death, in the representation of symbolism, and life, in that the living wore these jewels to acknowledge death as an inevitable factor of living. This resonates through royalty. Royalty had been constantly challenged and a society needed solidarity under a specific faith. Politics that began to govern, yet was now representing a people through an election. Fashion that crossed continents through its aesthetic qualities by being basically positive for people to view. When mourning encapsulates so much, an industry grows. The 18th century was a time of much turmoil for England, as much as the rest of the world, but opens up a global view of what would cement the modern concept of boundaries and identity. In the next Art of Mourning article, we will move into George III and see how identity creates colonies.