Jewels, Symbolism, Botany and Floriography

Victorian botanical research created the fundamental understanding of modern symbolic flora interpretations. Classifying the plants of the known world to a value of emotional fact was part of the Enlightenment’s late 18th century interest in aligning scientific understanding to all elements of life.

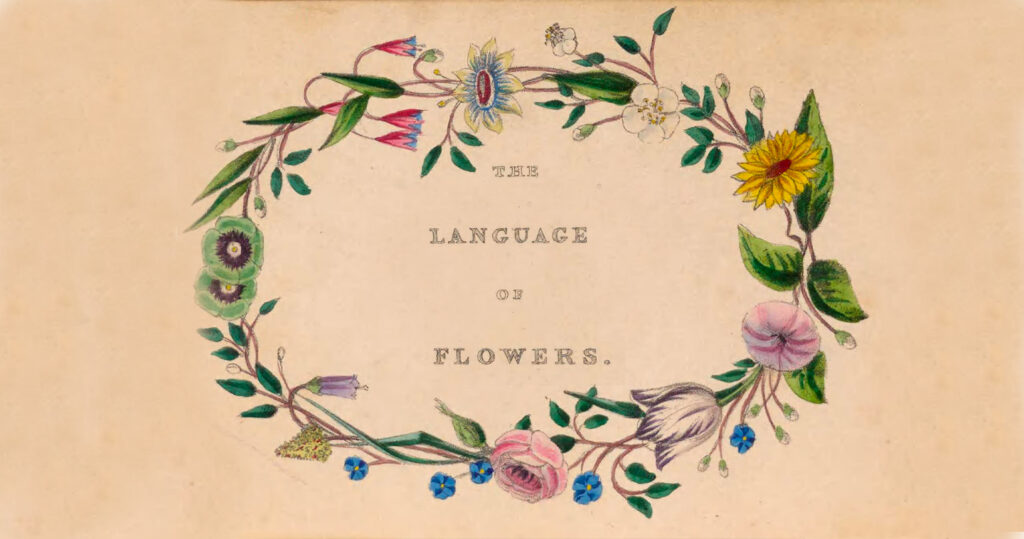

Historical and classical values of known species were carried into human rationale for what the particular meaning of a flower could be. International discovery allowed botanists to illustrate and travel back from foreign lands with new species. Joseph Banks (1743-1820), a notable naturalist/botanist, travelled with Captain Cook and catalogued an estimated 30,000 plant specimens and was the first European to document 1,400. Banks was the president of the Royal Society and advised George III on the development of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, sending botanists internationally to collect species of plants. His published work expanded the public’s fascination with the natural world and allowed authors to use these discoveries to publish their work. Henry Phillips’ Floral Emblems was published in 1825, The Language of Flowers with Illustrated Poetry by Frederic Shoberl was published in 1839 and The Illustrated Language of Flowers by Mrs L. Burke in 1856 set the standard for the botanical and poetic meaning of flora in jewellery design.

Known as ‘floriography’, the cataloguing of flora was an important philosophical exercise for understanding the meaning of poetry. The relationship between poetry and written English in jewellery relates directly to poesy rings and the designs of sentimental jewels. Men and women could customise their jewels with the designs of flowers, outlining the hidden meaning between lovers. In the 18th century, the English language was developing into a universally understood language through education and mass publication. Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755, bolstering the public’s accessibility to understanding the written word. The printing press allowed for gazettes, magazines and newspapers to be rapidly printed and circulated within society. The Enlightenment’s fascination with the cataloguing of the natural world, combined with the poetry of the late 18th century’s Romantic movement, led to a public demand for understanding the emotional/symbolic meaning of flora. Mary Wortly Montagu (1689-1762) introduced floriography to England in 1717, as she was a prolific writer and traveller to Turkey. Gazettes and magazines of the late 17th century published work from travellers about their adventures and ignited the public’s imagination. Her contemporary, Aubry de La Mottraye (1674–1743), introduced floriography to the Swedish court in 1727. One of the earliest publications was Joseph Hammer-Purgstall’s Dictionnaire du language des fleurs, published in 1809, followed by Louise Cortambert’s Le Language des Fleurs in 1819.

Floriography was developed alongside late 18th century colour theory, where philosophers catalogued colours towards their emotional and symbolic meaning. More on this can be found in the following articles:

Link > Colour Theory: Part 1

Link > Colour Theory: Part 2

Public accessibility to the meaning of flowers in the 19th century was essential to the meaning of jewellery. Giardinetti jewellery of the mid 18th century evolved from the Late Baroque’s Rococo evolution, which introduced many floral elements into the designs of jewels.

Giardinetti translates to ‘little garden’ in Italian and the style embraced floriography and colour theory fascination. Each flower and the way that it was positioned in the jewellery held a meaning for the giver and the wearer. Rococo designs of the 1700-1760 period were replicated throughout Europe, with aesthetic value being the primary reason for its popularity.

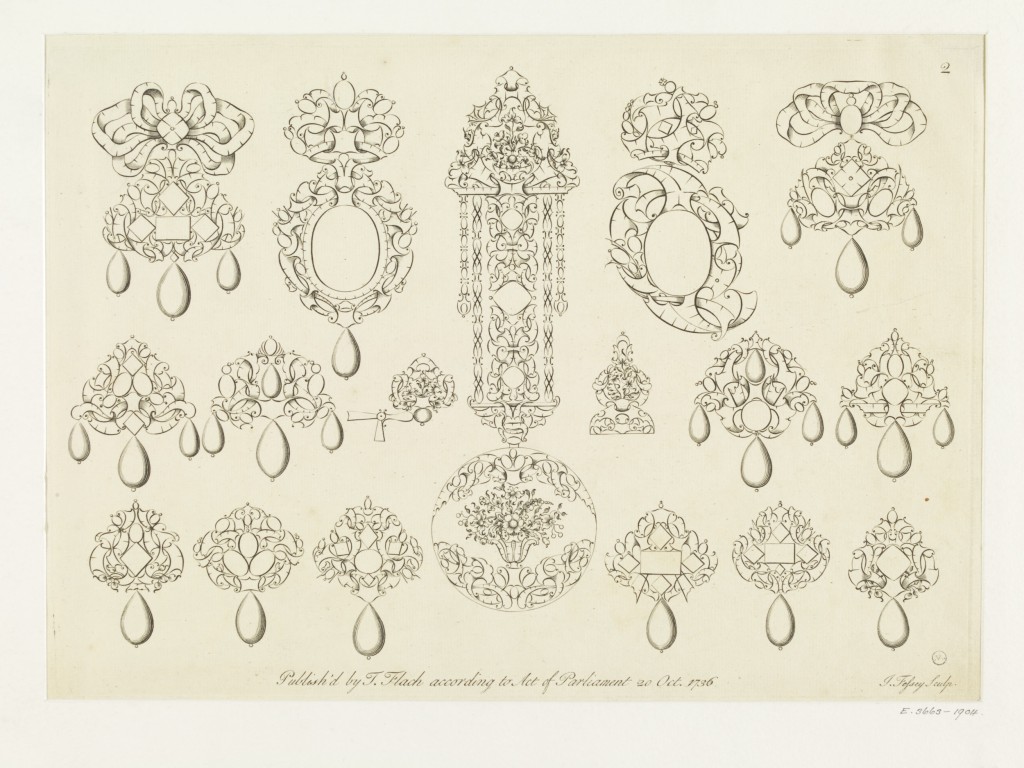

Thomas Flach was one of the designers who pushed the Rococo style forward in jewellery. His work is an evolution of European style, incorporating international flora from botanical publications and allowing their natural shapes to define the style of the jewellery.

This plate, from a series, in 1736 shows the progressive nature of his designs. Of note is the integration of the gems with the metalwork; the designs are interwoven. Gems offer the addition of colour theory in the meaning of floral jewellery, with the demand for the meaning of coloured gems outshining the rarity of the gem itself. Paste jewellery was introduced in the mid-18th century by Georges Frederic Strass (1701-1773), where he mixed bismuth and thallium in glass to improve its reflection and added metal salts to alter its colours. Metal foil was placed underneath the glass and this led to a simulation of the real gem. Trained in Strasbourg, he moved to Paris in 1724 and opened his own business in 1730. In 1734 he was granted the title of ‘King’s Jeweller’ and his work was in high demand in the court of Louis XV, allowing Strass to retire at the age of 52.

Paste jewellery and floral designs eclipsed the Neoclassical styles of the 1760-1820 period in the early 19th century. A social move towards organic styles also allowed goldsmiths to use the cannetille style, which featured fine gold wire or hammered sheets to emulate more voluminous style. Floral design accommodated cannetille due to its organic and flowing style, while the goldsmiths could make their jewellery look larger at a time when much of Europe’s gold was being put towards the Napoleonic War efforts. The price of gems had dropped in Europe since the French Terror, where many aristocratic homes were raided, the gold taken and the gems sold throughout Europe. Paste, being a foiled glass, became contemporary in value to the gems it was trying to emulate. The popularity of symbolism and meaning colour can be seen in the acrostic jewellery of the time.

Jewellery spelling out ‘DEAREST’ (diamond, emerald, amethyst, ruby, emerald, sapphire, topaz) or ‘REGARD’ (ruby, emerald, garnet, amethyst, ruby, diamond) set a new sentimental standard in loving jewellery during the c.1810-1840 period. Many of these styles were part of a young Queen Victoria’s sentimental education in fashion and set her knowledge of the meaning in gifting sentimental jewellery. Since her coronation in 1837, the jewellery she was given by her husband Albert, and her fashion, were widely publicised and emulated by the court and public.

Flowers, colour, gifting and jewellery tokens of love were all set in the public’s imagination by the mid-19th century. Combined with the Industrial Revolution, education, access to new wealth, urbanisation and increasing Victorian leisure time, rapidly produced jewels disseminated throughout society with a seemingly infinite variety of floral symbols.

Published parameters around social expectation and etiquette in fashion made gifting love tokens essential to Victorian behaviour; from purchasing a brooch when travelling to wearing a mourning jewel. The flowers and colours used were essential for social conformity and the publications of floriography were as important to understanding jewellery as the dictionary was to language.

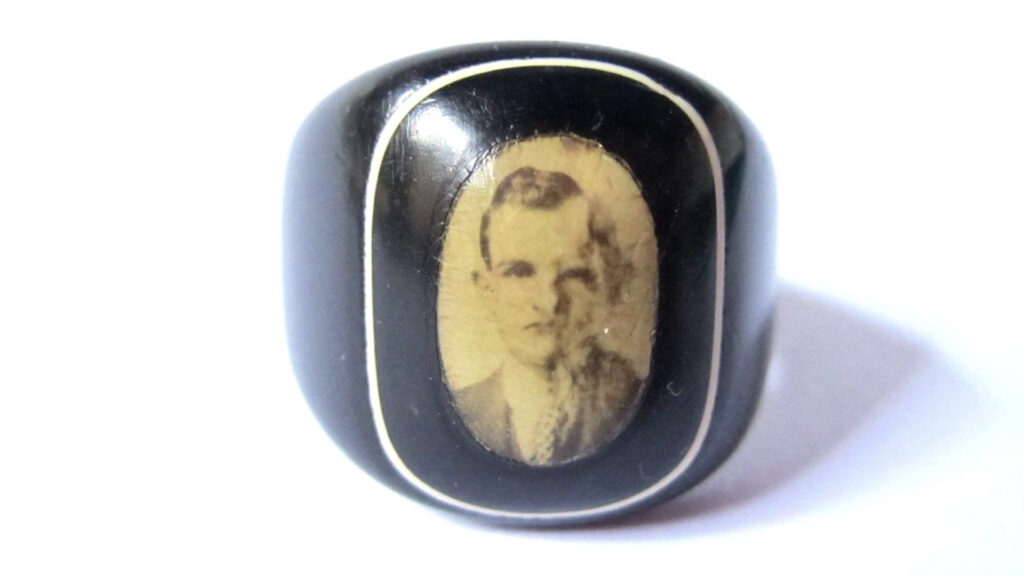

This essay is part of a series with the Whitby Jet Museum, to learn about their jet jewels featuring 19th century floral designs. Please read part one below: