“Love is the Bond of Peace” Skeleton Band

Death, as an identification of mortality in a mourning jewel, began using the most obvious tropes relating to the desecration of the body. As a token of remembrance, a mourning jewel with the Memento Mori symbolism of skulls, crossbones, hourglass, putti/cherub/angel, the scythe and all the grand statements of death, show powerful elements of grief, as well as a religious connection to the passing into the afterlife.

From the early 17th century, the mourning ring was developing into the style which would popularise the developing mourning industry from the 1680s. Regardless of the popular artistic influence in mourning rings, there have always been two styles which dominated their design. One is the band, with black/white enamel inlay and the dedication to the deceased, or symbolic motifs. The other is the ring with a bezel housing either hair, a gold initial cypher/symbolic motif on material/vellum or gemstone. These two fundamental styles would carry through from the 17th century to the beginning of the 20th and the end of the mourning industry.

To understand the ring focused upon in today’s article, we must learn about the popularity of the Baroque period and how that art influence led to the elaborate designs seen in its inlay. A look towards previous mourning jewels and the popular styles which defined them will show the transition and a viewing into what mourning rings would become immediately after this style is important.

There are a confluence of different elements which made this ring so particularly sentimental for its time, a time when the Age of Enlightenment caused a paradigm shift from the dominant ecclesiastical thinking to a new consideration of the self and the exploration of scientific and academic thought. This ring shows the Baroque influence of the design through the stylised skull and the floral elements, which are heavily designed and quite dominant throughout the band. This style of design would not exist if it wasn’t for the Protestant challenge to Catholicism and the socio-political shift within Britain that challenged previous thought.

Mourning bequeathments had been in popular thought since the late 16th century, but became indoctrinated through the 17th century. Most famously, William Shakespeare in 1616 declared that in his will that his daughter and wife should have rings stating “Love My Memory”. Samuel Pepys bequeathed 123 rings upon his death in 1703. These rings were graded into three classes and given out according to proximity of friendship and social status. So typical as a token of giving at a funeral, Pepys wrote in his diary:

“This day my Lady Batten and my wife were at the burial of a daughter of Sir John Cawson’s and had rings for themselves and their husbands.” – July 3, 1661

The period of the second half go the 17th century was the time of the Restoration of the British Crown and a time when industries were growing to accommodate a growing middle class through technological advancements. Through this, the custom of highly produced rings led to cheaper cost. Robert Walpole, Earl of Oxford, died in 1700 and bequeathed 72 rings at £1 each to friends and family, based on the same principles as Pepys.

Memento Mori Evolves

Memento moro, meaning ‘’remember death’ and remember you must die’ is a sign of mortality and final judgement. The concept of death being a factor that can happen at any moment is a message to the wearer or viewer of the symbol that life must be savoured to the moment and that final judgement awaits all. It is part an ecclesiastical statement as well as one of the intellectual and aristocratic, who could afford to adorn themselves with the memento moro symbolism. It is a statement that is ancient, with Roman depictions of memento moro joined with statements such as ‘Eat, drink, be merry, for tomorrow we die.’

Catholic domination during the middle ages utilised the memento mori symbolism greatly, instilling the values of being judged for the life you lead. Sentiments such as ‘Dye to Live’ inscribed within a memento mori ring adds to that statement, for the afterlife is the true essence of being.

Following the Restoration, Great Britain had suffered a shock to its primary values of religion and politics. In the space of three generations, the Catholic Church and the Crown had been destabilised, with the Restoration of the Crown building around a new society with new values of the ‘self’. This didn’t take away religion, but questioned the purpose of living, bringing back many of the life statements surrounding memento mori. Intellectuals and the aristocracy could wear jewellery with the memento mori symbolism and show their pursuit of a better physical existence.

With this affectation, the symbols also continued their meaning of mortality and their use in mourning jewels grew as the mourning industry grew. In the piece from c.1600, there is an early representation of the skull in an Elizabethan design. This is the nexus between the change of the symbols being decidedly mourning and previously for the statement of living.

It was the popularisation of crystal, commonly known as the ‘Stuart Crystal’ c.1603-1714 in England, during the 1680s, which popularised the look of memento mori symbolism. Seen most commonly in rings and ribbon slides (worn at the neck or cuff), oval shaped bezels with faceted crystals reflected the light in the same way as a faceted diamond would. Underneath, gold wire cypher initials being flanked by memento mori symbolism and placed on top of hair, material or vellum was a way to display identity and relationship status through a jewel on the self.

Baroque influences upon these jewels began to enter through the 1680s, but became more common at the turn of the 18th century. Shapes became more rectangular in brooches, slides and bezels, with sharper facets between c.1700-1720. Memento mori symbolism was adapting to the new styles and were the main designs for mourning representation. Objects of the body or the afterlife to denote mortality were flanked with Baroque design elements through floral motifs, such as the acanthus entwining flowers. Much of this is a reaction to the dominant architectural styles seen in other physical designs, which leads the jewels to adapt to fashion.

Romantic influence in contemporary sentimental jewels led for the heart motif to become popular and influence the worn statement of love for a jewel. Most popular being the ‘Georgian Heart’ motif, which can be seen below:

Following this, the Rococo period used the existing memento mori/Baroque styles and morphed them into a much more elegant and organic design. Bands became highly decorated and twisted into ribbon/scroll motifs, the infusion of greater floral elements was an adaptation of the dominating Baroque style and the bezels on mourning rings became smaller. It wasn’t until c.1765 and the introduction of the Neoclassical period that the greatest challenge to the memento mori style would essentially relegate it to become an anachronism.

Influence of the Baroque

Wearing a jewel to show that you will be judged and to live life for all its benefits is quite a grand statement during times with high mortality rates and a more feudal-based system of government, but during the 1670s-80s, there’s a strong shift to higher industry, specialised work and education. Politically, England was recovering from a civil war and the reinstatement of the kingship in Charles II in 1660, the Great Plague of London in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666. There was a high mortality rate and Charles II was only beginning the process of the Restoration. Hence, pieces like this could allow themselves to become more commonplace, the symbols of death could be appropriated for an industry that was reacting to the execution of a king and a subsequent civil war, it could pick up on the nuanced tokens of affection that became popular from this and it could produce a product that was relatively easier to produce and almost the same to sell.

Several events during the reign of Charles II led to the jewels of mourning and affection that dominated through to the 19th century. These being a combination of the Great Plague of London in 1665, with a mortality rate of an estimated 100,000 people, causing the king to flee London to Salisbury in July 1665. The Great Fire of London in September 2nd, 1666 was another such occurrence that, while not causing the high mortality rate of the plague, decimated London (13,200 houses, 87 churches) and left a lasting impression on a culture that had been challenged through political and religious thought.

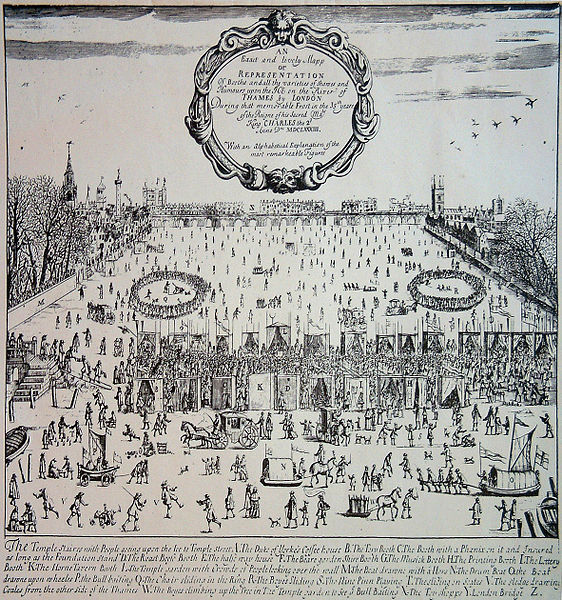

Combine with this a period of cold, during the “Little Ice Age”, where the River Thames frosted over. One such notable event was the Great Frost of 1683-84, with a two month frost that led to 11 inches of ice depth in London.

Connection between communities was advanced through the use of written language, particularly that within chapbooks. Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written in jewels, particularly inside posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content.

Society was at a point where events had overtaken the immediacy of global rule and communications that didn’t end at the limit of a village. Now, the world had opened up in ways which forced society to accept the relationships developed on a personal nature to be the truth, beyond religious or crown judgement.

In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

As the Protestant Reformation was such a reaction to the Catholic Church, the Baroque style was encouraged from the early 17th century as an emotive way of influencing and dominating art with religion. It is an imposing style, particularly in architecture, with an opulence and power that seems all pervasive, particularly when used in context of religious places of worship.

The influence of Baroque design upon jewels was prodigious, particularly as this ring comes under the Late Baroque period (c.1660-1725), where particular designs were standardised. These floral motifs and straight edged band with the stylised skull in the centre react to the popular mindset of Protestantism, due to a population that wasn’t wholly controlled by the Church of England and that the message of the designs were popular for the sake of being common.

It is remarkable how the balance of the skull on one side is entwined within the various floral elements. There is no immaturity to the design, but simply an element of design that works in the context of the heavy floral flourishes. The ring depicts death in a way that would be beautiful for the time, honouring the memento mori, but making it much more decorative. Considering that the Baroque design was created to intimidate and inspire, the integration of the skull almost works against its solidarity, especially compared to the earlier, sterner memento mori styles.

Connection to the Posie

Posie rings, otherwise known as ‘poesy’, ‘posy’ or ‘posey’, are one of the primary catalysts for the mourning and sentimental rings that generated their own industry post 1680. This ring shares many of the similarities of a sentimental posie, from the shape of the band to the inscription ‘Love is the Bond of Peace.’

Without the standardisation of the English language and the written reliance on Latin previous to the dictionary in 1755, posie rings are a remarkable time capsule for phonetically capturing their surrounding language in a jewel. From a status perspective, this utilisation of language is accessible to a strata of society that didn’t have the luxury of formalised education, opening up sentimental jewels to new levels of society. Basic sentiments of love etched into silver and gold bands could now be given as a secret love token for a growing middle class. In rings previous to the 16th century, more common would be the inscriptions written in French, Latin and Norman French.

Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written inside the posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content. Here, the relation of the ring to the popular literature is the key factor in understanding just how the posie’s relation to society. They were jewels that could be for the commoner, but also transient as a style of love token through society because of their simple statements.

Look towards the nature of hair and its status as a gift in jewellery from the 17th century. Prior to the rise of the hairworking industry and its prominence in mainstream jewellery, gifts of hair were considered tokens of affection and love between two people. Bury refers to The Relique (or The Relic) by poet John Donne (1572-1631) and its very early reference to a hair bracelet:

“When my grave is broke up againe

Some second ghest to entertaine,

(For graves have learn’d that woman-head

To be to more than one a Bed)

And he that digs it, spies

A bracelet of bright haire about the bone,

Will he not let us alone,

And thinke that there a loving couple lies”

Donne speaks in metaphysical terms about the unifying nature of spiritual love, as when he and his lover are dug up, they remain the symbol for holy and eternal love. From this, the poem is an excellent perspective on the sentimentality of hairwork at the turn of the 17th century. Wearing hair was an encompassing symbol of union and love between two people.

Donne wasn’t unique in his wearing of a hair bracelet, however, as Count de Grammont viewed several people wearing hairwork bracelets in the Court of the restored Charles II, circa 1660. This ties in with the rising prominence of other sentimental jewellery at that time. From love tokens, such as posy rings, to hair woven under crystal in slides, brooches, rings and other forms of jewellery, sentimental jewellery was rapidly evolving over the 17th century. Within these forms of sentimental jewellery, the use of hair became ever more prominent. Another example from 1647/8 of the popularity of hairwork within mainstream culture can be seen in Mary Varney’s letter to Sir Ralph Varney, asking to send locks of their daughter’s hair “to make bracelets? I know you could not send a more acceptable thing than every one of your sisters a bracelet”. At the time, Ralph was living in exile in France during the Protectorate. Hair tokens within families was the more common practice, but as jewels grew as a social device, so did their nature as a personal statement.

Indeed, the period surrounding Charles I was steeped in the growing sentimental culture, bolstered by Charles II and his support of the arts. Fundamentally, however, the act of having a keepsake of a loved one was intrinsic to the self. This influence of the human being important was born from religious challenge at the time.

With the sentiment of this ring written on the inside, later 18th century rings would adapt the sentimental message and dedication to be inscribed in the outside of the band and filled with black/white enamel. What this ring shows us is that the balance of the Baroque design and the interior message relates very closely to its predecessors and the personal message of love that a posie would house.

Black Enamel and Mourning

Black enamel seen in this ring is part of its Baroque design and the statement of death that it brings. This is the fundamental basis for the appropriation of black enamel as a mourning style within bands that lasted through to the beginning of the 20th century. Within this particular style and its Baroque elements, the Gothic Revival movement of the early 19th century adapted much of these concepts to popularise and set black enamel bands as being the primary identifiers for mourning rings. Queen Victoria’s perpetual mourning and the rise of mourning fashion in popular society made mourning rings highly identifiable. This was even more important in its context, as the perfect ‘Christian Family’ in the Victorian era put the female at the centre of mourning and had to convey the correct stages of mourning for the family itself.

Note the above ring. This piece from the 17th century shows the use of black along with the Baroque elements as the skull/crossbones motif. Enamel itself was a popular technique which carried over from Elizabethan times and developed with the more elaborate designs of the Baroque.

Highly raised bezels with the stepped enamel designs surrounding the underneath was popular through sentimental jewels and mourning rings benefitted from this through the contrast of black and white enamel.

Black enamel production developed enough to accommodate even more elaborate decorations, such as the above skeletal band on the early 18th century. Due to the influx of highly skilled Huguenot goldsmiths, finer quality could be made bespoke, for individuals as well as having more unusual designs created in higher production for funerals and bequeathments.

A Baroque Bequeathment

A ring like this must be admired for its personal statement of love. Indeed, it is the ‘bond of peace’ which will cement the relationship between the person who wore it and the one they loved, for they are at peace and they will be united. For its style and time, this ring must be appreciated as a statement of transition and appreciation. Knowing the various cultural, religious and political changes which made it possible to exist, it is remarkable that such am individual statement of love and art could exist. It captures a moment and a time which will resonate forever.