Bones and Rings

Connecting the body to death and the physical elements of the body that are relevant to display within the context of death are very specific to the Protestant and Catholic schism. Since Martin Luther proposed a discussion in his Ninety-Five Thesis, or the “Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” on October 31st, 1517, the focus of what the importance of life and judgement under god came into discussion. Mourning jewellery can find its inception to this period, as the questioning of ecclesiastical rites and power promoted a new vision of humanism. A rising merchant/middling class that had access to new wealth, new educational systems and the potential to be socially mobile challenged what it was to be alive and the values that a good life and a good family could live within.

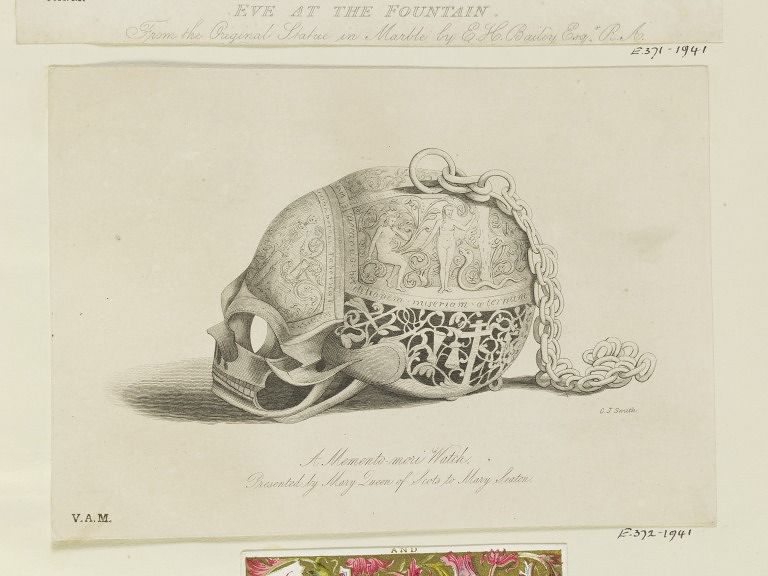

Presenting the elements of the body in ecclesiastical jewellery was common, yet the ring that is displayed today from the V&A collection has a basis in this thought, yet is an evolution of its own modernism.

Not only does this signet ring feature bone underneath its bezel, it also has the important marking of ‘EDWARDxCOPE’ as the reversed inscription above and below the skull motif. This is a personal statement of Edward Cope, as the skull perfectly aligns with the sentiment of ‘memento mori’, or ‘remember that you will die’. Being a personal statement means that we need to do more research into Edward Cope’s life before any assumptions can be made about his ecclesiastical beliefs, however, it does align to a time during the c.1600-50 period when the shift in thought in Anglican society had moved into a second/third generation of being in the Protestant mindset. The skull and crossbones during this time would reflect a personal statement of living, as this is what Edward would have faced in terms of his time on earth; death is an eventuality.

A clear divide between the ecclesiastical and the personal happens when one can see the reverse of the bezel. Using bone as an element in a mourning jewel is highly unusual, as are any elements of the body that are not hair. Hair was sentimental; for the living it could regrow and it was a cheap material. For the deceased, there involved no desecration of the remains of the body, which was unorthodox and in some cases sacrilegious.

Teeth are a common element in sentimental jewels, however, not the human kind. Dating back to ancient times, teeth, tusk and other elements could be carved, polished and placed in a jewel. Horn was popular during the 19th century, however in the 12th-14th centuries, teeth were used from animals and set in rings, as can be seen below from the ring from c.1200-c.1300.

In the case of this wolf’s tooth, it is a magical charm. ‘BURO + BERTO + BERNETO’ is a sentiment to protect against toothache and the biblical phrase ‘CONSUMMATUM + EST’ are the last words Christ spoke on the Cross, used as a charm to calm storms. Using religious elements in personal jewels of the c.12-16th centuries was typical, as it was a personal statement during these times. People aligned with a saint and this would make their fortune and personal relationships stronger under the eyes of God. Magical properties of saints and holy figures only protected the person, the relationship and the family.

In the same way that these earlier pieces connected the person to a higher figure, the use of bone was for religious purposes, as can be seen in religious reliquaries. Collecting a holy element from a religious figure and keeping it in a locket or keepsake was well engrained in society. Travelling to a holy place and purchasing one of these reliquary tokens was not affordable for everyone, which made it special as a status token for the wearer.

If this ring was made as a special token of connection to a higher purpose for Edward, this element is lost to time. What a modern viewer can discern is that it is unusual for a mourning jewel and not typical that bones of any loved ones were used in memento mori jewels.

Memento Mori and its Impact

Presenting the elements of the body as elements in jewellery date to the ancient. In medieval times, their connection to god and status is the most important function. Showing a skeleton enforces reverence with a holy figure or for the fact that with death comes final judgement.

Early jewels that existed prior to the 16th century are fascinating for their connection to the styles and symbols of mourning. In order for a style be ubiquitous, there needs to be open communication about its message. A design or art style can be very regional and based on the skills and materials of an artist. What was relevant in central Europe could be quite different in the north or south. Religious and ruling classes defined the styles, as they could afford to pay the artist, guild or school to promote an idea. But, without mass transit, the ideas remained contained to certain regions. When a monarch travelled or a new trade route was discovered, styles changed through discovery and new exposure.

This ring was designed for the loss of a loved one in a time when the concept was being discovered. It is an English ring, which speaks to the nature of the memento mori style. Art styles, such as Baroque, can be dominant in its grandeur and glory to provide this awe, yet nothing speaks with more depth than the symbols of memento mori. Memento mori is the literal depiction of death and decay, showing blatantly that life is fleeting and a person will be judged. Human adaptation of this art changed throughout the years, specifically from c.1400-1900 as our philosophies and technologies changed around us.

The ‘Western Schism’ or ‘Great Schism’ from 1378 to 1418 effectively split the Catholic Church, with numerous people vying to claim the true papacy. The end of the Avignon Papacy came on January 17th, 1377, where Gregory XI returned it to Rome. A year later, Gregory died, causing a Roman riot to ascertain that a Roman was going to be pope. Pope Urban VI, born in Bartolomeo Prignano, the Archibishop of Bari was elected, causing destabilisation due to his outbursts of temper and a reformist leanings. Robert of Geneva (Pope Clement VII) was elected as a rival pope on September 20th, 1378 and established a court in Avignon. While there had been challengers to the papacy before, this was a schism by the leadership of the Church that represented a true break down of their processes.

Breakdown in religion is the first factor in the destabilisation of modern societies. Any indoctrinated form of rule can create its own style, making symbolism identifiable and ubiquitous. When symbols are easy to understand, their language transcends words; they are visual markings of status and community. In the above rock crystal carving c.1450-1500, the depiction is the face of a young woman with hair parted in the middle on one side. On the other side is a death’s head with the lower jaw broken away. What is nebulous is the reflection of the eye sockets aligning to the girl’s eyes perfectly, showing the decay and mortality of life. Whether this was done on behalf of the artist or not is lost, however, what is important is that this carving was from France in a period following on from massive questioning of religious legitimacy.

For France, the Hundred Years’ War had lasted from 1337 to 1453, with the House of Plantagenet war against the House of Valois. This is effectively the rulers of the Kingdom of England vying for control of the French throne. Throughout the various rulers that lasted until its end, the mortality rate was something which required a populace to consider its reason within a hierarchy that used it to live and die by its own command. With this insecurity in both government and God, an introspective reflection on what mortality meant became important.

All of these factors are reflected in this early mourning ring. Society had moved from having the Christian elements of death as being the singular symbols of memory in death, such as images of Christ and its symbols. More questions about death being a final outcome of a difficult and challenging life is seen in the worm and skulls designed into the ring. The body is all that remains, so living a life of fulfilment is the way to honour oneself and the deceased. Increasingly morbid jewels further developed these concepts, until the birth of the mourning industry, which began during the English Restoration of Charles II, around c.1680.

Made in the France or South Netherlands c.1530, this ivory rosary/chaplet reflects the memento mori symbolism, within the Christian paradigm. This luxury item was made for the French and was considered highly fashionable. A chaplet was a device for keeping count of the number of prayers in both the rich and the poor. Its beads consisted of ten ‘ave’ beads, which were for the ‘Hail Mary’ and the larger beads that can be seen were for the ‘paternoster’, which was for the ‘Our Father’ prayer. Memento mori is seen within prayer to show the immediacy of death, or even ‘Death’ as a physical presence. This can be seen in the reflection of male and female heads, where death is literally becoming the subject. With these elements, artists could add further memento mori elements, such as worms, crawling from the skull.

As symbolism of memento mori started to permeate beyond just the literal form of decay, it begins to represent what it means to live as an individual within a society. In 1517, Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses challenged ecclesiastical thinking, leading to the Protestant Reformation and creating a backdrop of discourse which enabled Henry VIII to separate the English Church from Rome in 1534. This was the result of a series of events, including Henry’s annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the English Reformation and Lollardy. As a result of each of these forces, the period of the 16th century to the turn of the 17th century saw the establishment of concepts surrounding mortality and life in Europe. For a time when ecclesiastical figures dominated art and chastity and utilitarianism defined the nature of lower/middle class costume, challenges to defined groups within society became acceptable.

Within the context of the ‘Great Schism’, this rosary shows how rapidly the style of the human condition had changed within ecclesiastical praise. Death, as a symbol, was making a popular impact upon how people wore their own faith. Its incredible carving is an evolution of the immature style of the previously seen skulls and heart motif in the 15th century ring, however, it came from a place with greater Catholic value. Death, as a message, was being carried across the continent through its absolute symbolism of decay and mortality. Considering this was used within daily ritual in the ‘Hail Mary’ and ‘Our Father’ prayers, this rosary was a functional part of the day, to hold on to and to use when ‘talking’ to God.

This above coffin from 1540 shows how the memento mori designs had evolved in the mid 16th century. Purchased in 1856 by the V&A Museum for £21, the piece was considered to be found on the ground of Torre Abbey, Devon. Henry VIII ordered the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s, yet this jewel is from just afterwards, when the abbey was converted into a private house. The assumption is that this comes from the Cary family who lived in the house from 1662 until the early 20th century.

Several elements can be taken from this pendant’s construction. The first is that after 1662, there is internal solidarity in England. To have a family be so held to such a specific property from the 17th to the 20th centuries shows establishment of a central government or crown.

Otherwise, the jewel itself is a basic establishment of what mourning jewellery would become. The industry of mourning hadn’t begun until the 1680s and the Industrial Revolution which could mass produce (or at least increase) jewellery and textile production. Note how in the space of fifty years, from the earliest mourning ring seen, this pendant shows all the near perfect styles of symbolism that would be locked into place. Any lack of stylisation of to the skeleton itself is held within the naivety of the design, while in further examples in this article, there are 17th and 18th century pieces that are highly stylised.

The skeleton is literally depicted within the grave; the lid itself is heavily decorated with medieval and Celtic design patterns. The skeleton does not look directly at the viewer, which would indicate upwards to the heavens, but north. Its hands cover the middle-section, and not the folded over the chest, which shows some modesty in the design itself. It is an exquisite piece that details all the affectation of personal sentimentality in death and life; a sentiment of using art as a demonstration of death that would relate to what artists interpret within their own art.

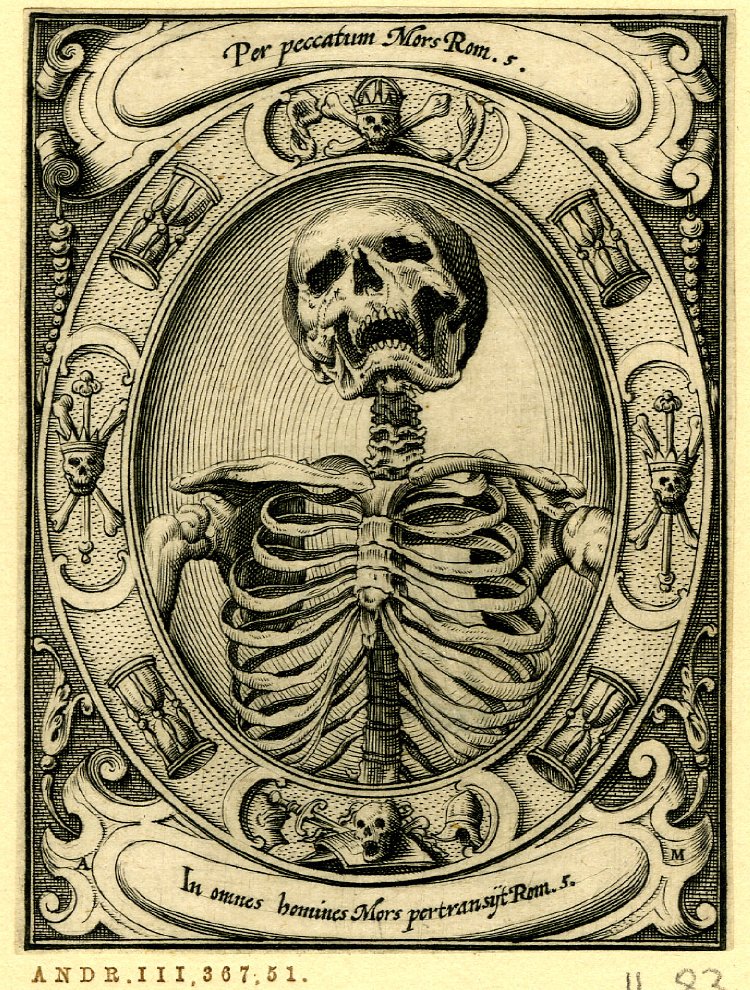

By the 17th century, memento mori had become an evolved symbol in art, and was used as the established design for death. All the elements of memento mori are displayed in this c.1605 print in perfect display and design. From despair in the visage of the skeleton (reflected also in the 1540s pendant), the tempus fugit symbols are all complete and seen in jewels and art even today. The transition from the 16th to 17th century marks a change in how the wearing of memento mori evolved from more intimate items reserved for high status in the aristocracy to more attainable jewels and items that were being appropriated for mandated periods of mourning.

At the turn of the 17th century, there was a marked change in how death was interpreted in jewels. Mourning bequeathments had been in popular thought since the late 16th century, but became indoctrinated through the 17th century. Most famously, William Shakespeare in 1616 declared in his will that his daughter and wife should have rings stating “Love My Memory”. Samuel Pepys bequeathed 123 rings upon his death in 1703. These rings were graded into three classes and given out according to proximity of friendship and social status. So typical as a token of giving at a funeral, Pepys wrote in his diary:

“This day my Lady Batten and my wife were at the burial of a daughter of Sir John Cawson’s and had rings for themselves and their husbands.” – July 3, 1661

There is a change in society which could afford jewels created at an attainable cost.

While jewellery is worn art, painted art is what we look towards as the first catalyst of style for this time. In this oil painting by Jacob van Walscapelle (1644 – 1727), the nature of memento mori within the wilted flowers is clear. Allegorical statements of the early modern era needed to relate toward Christian paradigms, hence this painting has the wilting bouquet of flowers and a wheat stalk with insects in the blooms. The wheat, being the basic ingredient for bread and the grapes, producing wine, are an elusion to the Eucharist. Butterflies here are considered to be a metaphor for the resurrected soul and the wilting flowers are a vanitas (memento mori) reflection. There is a marked change in the way that memento mori had entered the popular mindset.

It was not uncommon for wills to contain bequeathments to use the symbols as the representation of human decay only amplified the message of that time flies and that humanity ends with the investable death. With that in context, larger items could be worn around the person and show the memento mori affectation in proud fashion. This watch, made by J C Vuolf, was made in Germany c.1655-1665 shows the human skull in a silver case with the lower plate/jaw hinged at the back. On top is the winding hole and a silver hanging loop. The watch is inscribed with:

vita fugitur / life is fleeting aesterna respice / look down upon a fallen thing caduca despice look upon eternity incertita hora / death/hour is uncertain

Consider that these statements were worn in a very public way. There’s no allusion to the motifs of memento mori, rather, they are emblazoned as a statement of living for the wearer.

The watch was a great catalyst for the advent of the popular wearing of the chain. From the time of Henry VIII, wearing a watch as a pendant near the waist became a fashion. On January 1-2, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the noted diary writer wrote on January 1-2 1668 “..and took coach and home about 9 or to at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing…”, indicating the importance of status to wearing such a timepiece on the body. Affluence in the timepiece demands an equally adorned chain to hang it by.

While the chatelaine was also worn with equality between men and women; its development and craft was led by the influx of Huguenots emigrating to Great Britain. This influx created new skills through which finer jewels could be produced. In the case of these watches, however, their importance to making a personal statement is as bold as the Neoclassical period and its adherence to classical art, culture and fashion. The larger a jewel or accessory can become in fashion relates back to the individual’s personal statement on living.

Watches and clocks with the memento mori motifs were not uncommon, dating from the mid 17th Century to the 1930s. This early Verge silver skull pivots at the top of the cranium, whereas others pivot from the jaw. There are others created that fold open at the top of the head with enamel and diamonds, but pieces like these are extremely rare and command a high price. Examples exist from Switzerland, France, Germany and England. As written by the Taft Museum:

“The skull and watch are part of the standard subject matter of 17th-century vanitas still lifes. Vanitas is from the Latin for “emptiness” or “untruth,” from which comes the English word “vanity.” Such pictures depict objects that have an underlying moral message—usually about the fleeting nature of physical reality. Therefore, it is not surprising that the skull and watch, two reminders of the passage of time, should merge in a single object. The use of the skeleton hand, however, is unusual.”

Vanity is a wonderful term to consider memento mori of the 17th century. It reflected back on the lifestyle and politics of the wearer. Utilising these elements of death or love had previously been relegated to those who could afford the affectation in fashion, but now, there was an element of society that existed which could live for the pursuit of philosophy and challenging thought.

The evolution of memento mori would not have been possible without the political and social turmoil that resulted from the Schism and destabilisation of governments. Wearing a jewel or accessory from the 17th century onwards only added to the convictions of what the wearer felt, whether that be a move away from the Catholic Church or an alignment towards it. For example, the below ring would not have been possible without the establishment of the Church of England:

The concept of death being a factor that can happen at any moment is a message to the wearer or viewer of the symbol that life must be savoured to the moment and that final judgement awaits all. It is part an ecclesiastical statement as well as one of the intellectual and aristocratic, who could afford to adorn themselves with the memento moro symbolism. It is a statement that is ancient, with Roman depictions of memento moro joined with statements such as ‘Eat, drink, be merry, for tomorrow we die.’ Catholic domination during the middle ages utilised the memento mori symbolism greatly, instilling the values of being judged for the life you lead. Sentiments such as ‘Dye to Live’ inscribed within a memento mori ring adds to that statement, for the afterlife is the true essence of being.

Following the Restoration, Great Britain had suffered a shock to its primary values of religion and politics. In the space of three generations, the Catholic Church and the Crown had been destabilised, with the Restoration of the Crown building around a new society with new values of the ‘self’. This didn’t take away religion, but questioned the purpose of living, bringing back many of the life statements surrounding memento mori. Intellectuals and the aristocracy could wear jewellery with the memento mori symbolism and show their pursuit of a better physical existence.

Jacobite (Latin: Jacobus/James) rebellions continued between 1688 and 1746 were instigated to restore Stuart kings to the thrones of Scotland and England. James II and VII was deposed in the Glorious Revolution in 1688. James was considered to be pro-French and Catholic, leading to William III of Orange to invade from the Netherlands. James was succeeded by William III & II and Mary II, who were married – Mary being joint sovereign of England, Scotland and Ireland. Mary II passed on in 1694, William became the singular ruler. Throughout the shared reign, the Jacobite resistance promoting the divine right of kings challenged the rule, stating that the throne is a rule of God and not dictated by Parliament. Over 400 clergy and many bishops of the Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church refused to take an oath of allegiance to William. Parliament majority of the Whigs supported William, with fluctuating support by the Tories. Wars against Louis XIV of France kept William away from England, during the time when Mary was alive, letting her govern, wasn’t resolved until the Treaty of Rijswijk ended the Nine Years’ War in September 1697. This statement of authority in William from Louis as monarch pacified the Jacobites to some degree.

With this affectation, the symbols also continued their meaning of mortality and their use in mourning jewels grew as the mourning industry grew. In the piece from c.1600, there is an early representation of the skull in an Elizabethan design. This is the nexus between the change of the symbols being decidedly mourning and previously for the statement of living.

It was the popularisation of crystal, commonly known as the ‘Stuart Crystal’ c.1603-1714 in England, during the 1680s, which popularised the look of memento mori symbolism. Seen most commonly in rings and ribbon slides (worn at the neck or cuff), oval shaped bezels with faceted crystals reflected the light in the same way as a faceted diamond would. Underneath, gold wire cypher initials being flanked by memento mori symbolism and placed on top of hair, material or vellum was a way to display identity and relationship status through a jewel on the self.

Baroque influences upon these jewels began to enter through the 1680s, but became more common at the turn of the 18th century. Shapes became more rectangular in brooches, slides and bezels, with sharper facets between c.1700-1720. Memento mori symbolism was adapting to the new styles and were the main designs for mourning representation. Objects of the body or the afterlife to denote mortality were flanked with Baroque design elements through floral motifs, such as the acanthus entwining flowers. Much of this is a reaction to the dominant architectural styles seen in other physical designs, which leads the jewels to adapt to fashion.

In the above ring, the Rococo elements around the band and the open shoulders lead into the crystal bezel with the memento mori skull and crossbones underneath. Even when a style changes, love and mourning symbols adapt. Romantic influence in contemporary sentimental jewels led for the heart motif to become popular and influence the worn statement of love for a jewel. Most popular being the ‘Georgian Heart’ motif, which can be seen below. The heart can be seen in the early mourning ring between the two skulls. As a symbol, this also developed along with memento mori, as the literal depictions of the body began to take significance for emotional meaning.

Following this, the Rococo period used the existing memento mori/Baroque styles and morphed them into a much more elegant and organic design. Bands became highly decorated and twisted into ribbon/scroll motifs, the infusion of greater floral elements was an adaptation of the dominating Baroque style, and the bezels on mourning rings became smaller. It wasn’t until c.1765 and the introduction of the Neoclassical period that the greatest challenge to the memento mori style would essentially relegate it to become an anachronism.

As can be seen in this above ring, by 1728, the symbols of death could be used in more creative ways, due to their standardisation. They had, by this time, lasted forty years in the hands of skilled artisans to refine and improve the memento mori designs for a growing audience. Access to to growing wealth and an industry that could provide for mourning jewels, made the requirement of a mourning ring as a bequeathment almost a prerequisite of family status. Of note is how the above ring even uses the coffin as the crystal memento for hair and another enamel skull and crossbones motif on top of the hair. The excess of the memento mori styles is locked to the first half of the 18th century. The skeleton around the band is stylised to the point where the face has additional personality, staring back in a sense of acknowledging that the viewer will be part of death, soon.

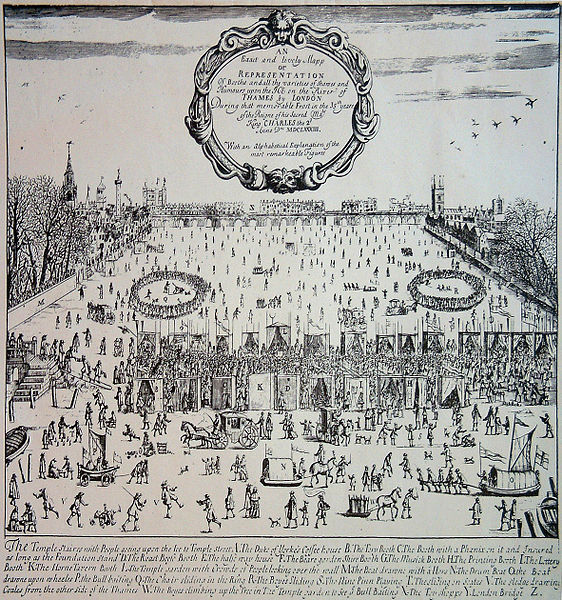

Several events during the reign of Charles II led to the jewels of mourning and affection that dominated through to the 19th century. These being a combination of the Great Plague of London in 1665, with a mortality rate of an estimated 100,000 people, causing the king to flee London to Salisbury in July 1665. The Great Fire of London in September 2nd, 1666 was another such occurrence that, while not causing the high mortality rate of the plague, decimated London (13,200 houses, 87 churches) and left a lasting impression on a culture that had been challenged through political and religious thought.

Combine with this a period of cold, during the “Little Ice Age”, where the River Thames frosted over. One such notable event was the Great Frost of 1683-84, with a two month frost that led to 11 inches of ice depth in London. Connection between communities was advanced through the use of written language, particularly that within chapbooks. Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written in jewels, particularly inside posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content.

Society was at a point where events had overtaken the immediacy of global rule and communications that didn’t end at the limit of a village. Now, the world had opened up in ways which forced society to accept the relationships developed on a personal nature to be the truth, beyond religious or crown judgement. In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

As the Protestant Reformation was such a reaction to the Catholic Church, the Baroque style was encouraged from the early 17th century as an emotive way of influencing and dominating art with religion. It is an imposing style, particularly in architecture, with an opulence and power that seems all pervasive, particularly when used in context of religious places of worship. Between the mid 16th and 17th century, this ring shows the influences of different socio-political influences that have led to its dominant memento mori motifs. from the Restoration and the reign of Charles II, there was no period of absolute peace, but this did begin a period of challenge to traditional thought and the rising of new industries. These industries could capitalise on new technologies and learnings of introduced talent into Britain and exploit this for financial gain. Death and taxes being two of life’s absolutes lead to a good profit being made from the act of grief and the requirement of presenting oneself in public with the trappings of grief when a loved one has died.

Considering the mortality rate in the mid 17th century was around 40, with even childhood being difficult to survive, and the message of this ring shares its honesty. Life was difficult and there were many opportunities to fight for a political ideal and get monetary rewards, which allowed for sentimental jewels to flourish. Capitalisation on these causes, as well as the various disasters, be they natural or otherwise, only played to the heart of love itself. As a population, we require the company and love of others, as well as their support. Without giving thanks to this concept in a ring or jewel, then the connectivity between societies and cultures does not lend itself to memory and learning through what has come before. If not for the generation that enabled the Protestant movement, then all that had been in the latter 17th century would not exist.

Resonating mortality for its time, this skeletal ring was at the height of its fashion and its sentiment. Surrounded by turmoil, yet reflected in love, the ring reflects several skeleton motifs and the desecration of the body. Why this was such a popular motif was the immediacy of death to the wearer and the viewer of the ring. At no stage is there any consideration for a beautiful life after death, or that the mourning is a sad occasion for opulent decoration – memento mori presents death at its most fundamental. This ring tells us: “Remember you will die”.

And so, the Stuart Crystals and the memento mori style become engrained within the mindset of modernity and the collector. In the above example, there is a box made of silver, combining several crystal slides and pendants. Though this box quite possibly stemmed from the 18th century, it shows just how the appreciation of the memento mori style had settled in a historical-looking context. These aren’t contemporary or built around a family, they are appreciated for their historical context even so close to their construction.

Compared to the pieces from the 15th and 16th centuries, they have an immediacy to their lifespan. They are built around the nature of death and judgement as a value, not as a requirement or as simply art. Vanity they may have become, but they are truly jewels of their time.

Holistically, what can be gathered from the combination of values from the 15th century to the 19th century? Society had come a long way and with standardisation of of symbolism due to mass trans-continental transit, colonisation and exchange of ideas and values, many of the barriers that had been through phases of discovery, conquest and rebellious identity establishment created a system of standardised symbolic value. Considering that the earliest examples seen in this article relate to Western society being confused by the turmoil of ‘people’ challenging for seats of power that were considered to be ordained by ‘God’, then the value of what that meant became less important. Value of living became more important and that value led to the representation of death as a very physical reality. Every day above ground becomes a great day and one of self/family improvement.

By the late 19th century, the symbols of memento mori had become anachronisms, removed from the simple statements of ‘IN MEMORY OF’ and black enamel. Showing a skull in its place wouldn’t be considered tasteful for its time, which makes elements of art that utilise this interesting. How were they depicted in society and how does society treat these fringe elements? The ossuary at Sedlec is a good example of what can come from this, but how this reflects in jewels is far more difficult to gather, as the memento mori symbols had become to be more appropriated by fraternal societies.

Memento mori needed to adapt as new styles came along. The reason for keeping a consistent mourning style over the period of the middle 17th century to the 1760s shows a society that is adapting a style, but not revolutionising it. The symbols of memento mori would not and cannot go away; they are integral to human identity.

Between the mid 15th century to the mid 18th century, memento mori was the very identity of death. Using the elements of the body as the symbols of mortality, such as the skeleton, to the symbols that shows the progression and decay of the body in the hourglass and worms, memento mori was designed to instil urgency and fear in the viewer. Knowing that you will die removes social, financial, and political systems of control from the individual and focuses living upon what is most important: Love.