An Eye Miniature Mourning Ring, Mary Dean Obt 27 Augt 1794 AEt.73.

Eye portraits are rare and highly sought after, but there is variation between them. In the portrait shown, the setting conforms to the portrait of the eye, but later examples show a tear-drop setting with a black enamel surround. Some also show a down-turned eye. These are not always to be considered mourning pieces, but certainly sentimental. The tear-drop setting with the black enamel surround is certainly a mourning piece and quite an odd point in the evolution of the style. The Neoclassical period fundamentally changed the interpretation of love and grief in jewellery post-1760. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought. What this ring shows is a swing towards the personal nature of death in jewellery; depicting the identity of the person in the way a full miniature would. How could this be such a popular style and why did Neoclassicism pave the way for jewels which directly represented its subject or treated hair with the equality of a gem? The turn of the 19th century was fraught with change and socio-political conflict, so let’s look at this ring and see how it developed its elements.

This oval-shaped mourning ring features blue and white enamel and is dedicated to the memory of Mary Dean, who died on the 27th of August, 1794 at the age of 73. In its use of blue and white enamel, one can assume that the subject was unmarried and virginal/pure (white enamel) and considered royalty in the use of blue enamel. The use of blue enamel (used for royalty and suggesting that one was considered royalty) contains many mixed histories. Over time, many of the messages surrounding cobalt glass and blue enamel have been crossed, yet it fit very well into the Neoclassical paradigm post c.1765. The main reason for its use in heavier, symbolic terms is that the Neoclassical reliance on sentimental depictions and the allegories of love put the reliance on peripheral representations, rather than clear-cut statements of love and faith. Hence, blue enamel, considered royalty.

There’s Royal Blue and there’s Bleu de France. Bleu de France has been representing France and the French monarchy and the heraldry since c.12th century. This was adapted into jewels and you can see the obvious connection there with the message of royalty, especially considering the French influx into other cultures, as the French were considered the focus of style and fashion.

Royal Blue, is darker, with a hint of purple and red. This was thought to have been invented by millers in Frome, Somerset during a dress making competition for Queen Charlotte post 1761 (after she was queen). There’s the connection here in that her style would dictate a lot of the aristocracy would consider high fashion.

Subtle decoration to the gold within the white enamel shows the delicate nature of the ring’s craft. Also of note is the oval shape, which correlated to a growing change from the navette’s tall north-to-south shape, which was most effective for depicting allegorical scenarios of love and death.

This new oval shape grew as did the popularity of eye miniatures, with the Regency period adapting more geometric shapes and infusing Neoclassical symbols within. In 1789, the French Revolution affected jewellery wearing and production to a great extent. The First French Empire under Napoleon retained and grew the popular Neoclassical styled jewels, maintaining their position as the primary leaders of fashion. Even with the hostilities between 1793-1815, the English closely followed Parisian styles.

By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles may be enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security if fleeing the country.

Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

With this massive change to what could be accessible in terms of materials, gem popularity in jewels began to replace the allegory of Neoclassicism. Oval shapes and gems took on parity with their symbolism and sentiment with the very hair of the subject for whom it was dedicated to. Creating a robust scenario with classical figures enacting Greco-Roman fables was still utilised in larger forms of art and in larger miniatures, but having this level of detail in a ring began to become less fashionable. Portraits were painted to a Neoclassical ideal, hence a subject could be tailored to suit the identity of the subject (hair colour, etc). Notably, those going off to fight in the Napoleonic Wars could sit for a miniaturist who would have the oval portraits pre-painted with the uniforms and quickly produce the finer details of the soldier. This provided a simple and fast keepsake for them to give to a loved one.

Eye portraits are considered to have their genesis in the late 18th Century when the Prince of Wales (to become George IV) wanted to exchange a token of love with the Catholic widow (of Edward Weld who died 3 months into the marriage) Maria Fitzherbert. The court denounced the romance as unacceptable, though a court miniaturist developed the idea of painting the eye and the surrounding facial region as a way of keeping anonymity. The pair were married on December 15, 1785, but this was considered invalid by the Royal Marriages Act because it had not been approved by George III, but Fitzherbert’s Catholic persuasion would have tainted any chance of approval. Maria’s eye portrait was worn by George under his lapel in a locket as a memento of her love. This was the catalyst that began the popularity of lover’s eyes. From its inception, the very nature of wearing the eye is a personal one and a statement of love by the wearer. Not having marks of identification, the wearer and the piece are intrinsically linked, rather than a jewellery item which can exist without the necessity of the wearer.

Use of materials developed along with the size of the settings of eye miniatures, as pieces were surrounded by precious stones and became larger due to altering fashion. A good reference for the evolving trend of the shape of early 19th century jewellery can be seen in the Rings section, where settings and the shape of the mementos changed quite dramatically from 1790-1830.

There have been a number of eye portrait forgeries due to their desirability and low production. Collectors should be cautious when purchasing a piece to ensure its authenticity.

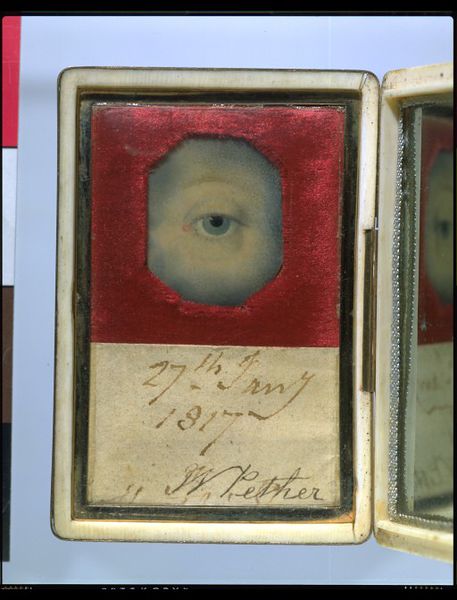

In the above eye miniature painted by William Pether (1733 – 1821), the eye is treated much like a larger portrait miniature for its time. It comes within an oblong ivory case, embedded in red velvet. Under the eye, “27th Jan’y 1817. W Pether” is written, with the opposite being a mirror. This compact would be a fashionable accessory to carry, hence the hidden nature of the eye still resonates. It’s not displayed as prominently as the featured ring for this article, but it is a personal loving message and a keepsake. Being held within a format that isn’t a jewel only shows how popular the eye portraits has become. They were understood for their sentimental nature, regardless of how ‘anonymous’ they seemed to be. Pether, a mezzotint-engraver, was a popular figure in the art community during the 18th century, being a fellow of the Incorporated Society of Artists, and contributed to its exhibitions paintings, miniatures, and engravings from 1764 to 1777. By this late stage, he had moved to Bristol and was largely removed from the art community, however, the quality of the eye miniature shows a great deal of empathy with the subject in a way that is quite sad and moving. Eye miniatures weren’t simply random anonymous portraits that were developed for the sake of basic cost in time and money, they provided an insight into their subject, which makes them riveting time capsules for this sentimental and loving period in time.