William Harry Vane Serpent Mourning Ring

Sometimes a jewel can be the very definition of its time. A ring, worn to be seen and never hidden, denotes the status of its wearer; shown as a token of sentimentality and personal affectation. This mourning ring for William Harry Vane, the 1st Duke of Cleveland (July 27th, 1766 – 29th January, 1842) is a perfect example of its time; encapsulating fashion, the social and visual interpretations of mourning and how grief was expressed.

Allocating mourning rings within the bestowment in a will had become a common element since the latter 18th century, particularly in the aristocracy. Bolstered by the high profile mourning periods of Princess Charlotte and the public mourning of Lord Horatio Nelson (each creating enough social outcry to create an industry of souvenir jewellery and mourning peripherals for each), the creation of jewels for the family and friends of a notorious figure in society was required.

In this ring, we can see the different elements working together, each lending themselves to become a significant token of mourning for Vane. The serpent is the obvious motif that creates the entire experience of the ring; it coils around the finger. With its diamond eyes, wealth is shown to a high degree; this clearly wasn’t a piece made for anyone less than a close family member or friend. The serpent is could around itself, showing beautiful detail in the black enamel inlay (a style very popular in the 1830s), and inside, we see the hallmarks and name dedication for Vane himself.

Underneath the serpent’s head is the hairwork dedication, with a lock of Vane’s hair simply woven and placed under glass. Since the turn of the 19th century and the influence of the Gothic Revival style, hair in jewels were being placed in smaller housings. This was part of the fashion of the time, as the larger Neoclassical oval and navette shapes had become smaller and would eventually become more popularised inside the jewel, rather than being placed upon the top/inside a bezel.

Much of the change in how mourning was presented was due to the social change bought about with the return to the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

William Harry Vane 1st Duke of Cleveland

Born in St James Square in London and educated by William Lipscomb, Vane was a whig who stood in opposition to the government and advocated political reform. He was the third sword bearer at William IV’s coronation and a noted sports player. Vane was survived by eight children.

William Carr’s Dictionary of National Biography, Errata (1904) tells the tale of Vane’s life:

“VANE, WILLIAM HARRY, first Duke of Cleveland of the second creation and third Earl of Darlington (1766–1842), was son of Henry Vane, second earl of Darlington, by Margaret, daughter of Robert Lowther, and sister of James Lowther, first earl of Lonsdale [q. v.] He was born on 27 July 1766 in St. James’s Square, London, and was educated by a private tutor, William Lipscomb [q. v.], and at Christ Church, Oxford, whence he matriculated on 25 April 1783. He sat in the House of Commons for the borough of Totnes from 1788 to 1790, and from 1790 to 1792 for Winchelsea, being then styled Viscount Barnard. On the death of his father on 8 Sept. 1792 he succeeded to the peerage as Earl of Darlington. In 1792 he became colonel of the Durham militia, and lord-lieutenant of Durham in the following year; and in 1794 he was appointed colonel-commandant of the Durham regiment of fencible cavalry. In politics he was a whig, and from 1792 to 1827 was generally in opposition to government. He, however, voted for the seditious meetings prevention bill in December 1819, and gave independent support to Canning’s administration and, subsequently, to that of the Duke of Wellington (Hansard, vol. xii. App. 1832, p. 115). He was an advocate of political reform, presented in the House of Lords a petition from South Shields on the subject on 3 March 1829, and proved himself throughout an influential supporter of the bill, and willing enough to abandon his six borough seats. He spoke seldom in the house of lords, and when he rose his manner is said to have been better than his matter (Grant, Random Recollections of the House of Lords). On 17 Sept. 1827 he was created Marquis of Cleveland, and on 15 Jan. 1833 Duke of Cleveland. Through his grandmother Grace, daughter of Charles Fitzroy, first duke of Southampton and Cleveland [q. v.], he represented the family for which in the first instance the dukedom was created.

The duke was more notable as a sportsman than as a politician. Living at Raby Castle for a considerable portion of every year, he proved himself an enthusiastic upholder of every form of sport. He commenced to hunt his father’s hounds in 1787, and spared no expense on his kennel. His hounds were renowned for their speed, and were divided into two packs, one of large breed and one of small; with these he hunted on alternate days. After each day’s hunting it was his habit to enter an account of the day’s sport in a diary, portions of which were privately published at the close of every season. He paid considerable sums of money to his tenants for the preservation of foxes, and on their behalf he successfully opposed the first Stockton and Darlington railway in 1820, because in its course it encroached on a favourite covert. In 1835 he divided his celebrated pack between his son-in-law, Mark Milbanke, and himself, and the old district of the hunt was at the same time apportioned. Almost equally enthusiastic in his patronage of the turf, he maintained a magnificent stud, and was rewarded by winning the St. Leger with his horse Chorister in 1831.

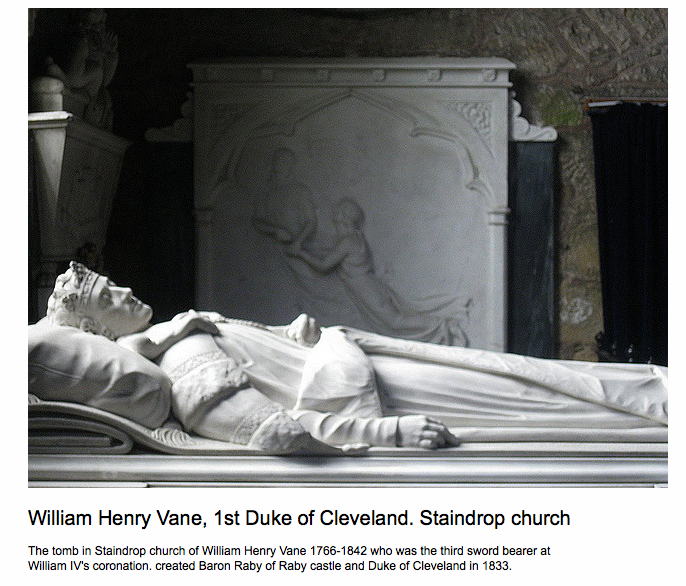

The Duke of Cleveland died in St. James’s Square on 29 Jan. 1842, and was buried in Staindrop church, where a magnificent monument was erected to his memory. Lord Brougham, whom he had introduced to the House of Commons as member for Winchelsea and who was a lifelong friend, was named executor under his will.

The duke married, first, on 17 Sept. 1787, Katherine Margaret, second daughter and coheir of Harry Paulet or Powlett, sixth duke of Bolton [q. v.], by whom he left eight children; secondly, on 27 July 1813, Elizabeth, daughter of Robert Russell of Newton, Yorkshire. He was succeeded in the dukedom by three of his sons in turn, each of whom died without male issue. The duke’s honours and dignities (except the barony of Barnard, which passed to a distant cousin, Henry de Vere Vane) became extinct in 1891 on the death of the youngest son, Harry George, who married Catherine Lucy Wilhelmina (d. 18 May 1901), daughter of Philip Henry, fourth earl Stanhope, widow of Archibald Primrose, styled Lord Dalmeny, and mother of the present Earl of Rosebery.

There are several portraits and miniatures of the first duke at Raby Castle; and a portrait by Devis, in the possession of the Milbanke family at Barningham, has been engraved by Fry.”

What’s relevant to note about this ring is that Lord Brougham was the executor of his will and thusly, directly responsible for the manufacture and allocation of this particular ring.

Vane’s incredibly elaborate burial at St Mary’s Church in Staindrop sits in the North West corner, where the tombs and memorials of the Vane family remain. Vane’s burial was carved by Richard Westmacott, president of the Royal Academy in white marble.

From the wealth of the family and the importance of Vane, it’s quite obvious to see why this ring is so culturally relevant; it represents its time in immaculate splendour. The serpent, the diamonds, the attention to detail in the enamel are all benchmarks that other jewels can look towards and aspire to. For a collector, using this ring as a symbol of the early 1840s is ideal.

Serpent

The snake motif was a popular symbol of eternal love, as it showed the snake ingesting its own tail, therefore representing eternity. Much thought has been given to Queen Victoria for popularising the snakes (as given to her by Prince Albert), however, this motif predated her usage by over fifty years. Victoria and Albert were married in 1840 and the engagement ring was a snake with an emerald-set head. As a catalyst for jewels, the royal family were the apex of style that resonated down through society; an element retained from George IV and his patronage of the arts. There are other connotations of the serpent in symbolic motifs, but for the relevance of the 19th century in jewels, this is the primary reason, much the same as the knot symbol. For further examples from the late 18th century on, please view the following:

Hallmarks (Who Made This?)

Hallmarking is the best standard to identify a piece, but unfortunately (although mostly illegal), jewellers are known to falsely stamp pieces. Hallmarking is the process of stamping precious metals, as they are intended to be stamped by the Assay Office to guarantee purity of the piece.

When collecting, it is necessary to bring a hallmarking book along to assist with the identification of pieces, as the listings are so vast that there is no way to fully comprehend each and every stamp.

This particular ring has pristine hallmarks that represent the year and the maker. The maker, in this case, is Thomas Spicer Dismore of Clerkenwell Green;

Born in 1787.

Christened at St Andrew, Holborn on 26th January 1787; parents Bateman and Sarah of King’s Head Court.

He married Sarah Hewitt on 17th January 1807 at Christ Church, Southwark; both were of that parish.

Christening records for 3 of their children have been traced at St Giles, Cripplegate in 1809 where Thomas was recorded as an engraver and at St James, Clerkenwell in 1811 and 1814 where the latter records Thomas as a jeweller at Clerkenwell Green.

Entered maker’s marks at Goldsmiths Hall in 1818 and 1821 in partnership with Thomas Downes and in 1825 and 1834 alone all as goldworkers at 11 Clerkenwell Green.

Wife Sarah does not appear on the 1841 UK Census. There is a burial record at St Dunstan, Stepney dated 28th March 1837 for a Sarah Dismore aged 59 years; last address M.E.O.T. (Mile End Old Town).

1841 UK Census for Milner Street, Islington as a goldsmith. Also resident was son George (born about 1811) also a goldsmith.

1848 Post Office Directory entry for Thomas Dismore & Son manufacturing jewellers at 11 Clerkenwell Green.

1851 UK Census for 7 Atkinson Place, Brixton as a retired jeweller.

1856 Post Office Directory entry for Thomas S Dismore & Son manufacturing jewellers at 23 Maddox Street.

1861 & 1871 UK Census for Cromer Villas, West Hill Road, Wandsworth as a retired goldsmith or jeweller

George Dismore a son in the firm of Thomas Dismore & Son died in 1875 leaving an estate of under £4000.

Thomas Spicer Dismore died in January 1879.

England & Wales Deaths Index for Wandsworth registry.

National Probate Calendar for Principal Registry dated 7th March 1879. Last address Cromer Villas; value of the estate under £16000.

Named as executor of both George and Thomas Spicer Dismore’s Wills was Thomas Dismore a jeweller of Bold Street, Liverpool. The Principal Registry extracts indicate a close family relationship to the deceased which has not been confirmed.

> Goldworkers List, Section (VII)

Black Enamel

The simplification of design in mourning jewels took on a form that would define the rest of the 19th century. One of the primary identifiers in recognising a mourning jewel is through the abundant use of black enamel. Black enamel, while common as the primary element in mourning jewels, often worked in conjunction with other symbols (memento mori in the 17th and 18th centuries, allegorical romantic symbols in the late 18th and early 19th centuries), but now it had begun to over take any other symbolism and truly take over the jewel.

Diamonds

Diamonds are the most precious of the gems to be found in mourning and sentimental jewels; often denoting what level of society would have commissioned the jewel. Throughout the 17th to 19th centuries, only the finest of the jewels created housed the diamond, along with the four other precious stones of the ruby, emerald and sapphire.

A symbol of fearlessness and love, the origins of diamond mining were in India, c.500BCE. From the early 18th century, diamonds were found in Brazil, leading to the rise in production in Europe through to the 19th century. The most dramatic finding of diamonds next came rom Australia in the mid 19th century and South Africa at the turn of the 20th century. Only by this time did diamonds begin to reach lower classes, as the cost had dropped considerably, but that doesn’t mean a diamond shouldn’t be graded for its condition. ‘Finest white’ is the highest grade for a diamond, with the next being ‘fancy’ (‘coloured’), with its associated colour.

Symbolic

As a jewel for its time, this ring combines all the elements of a mourning jewel that would be expected for proper mourning in the 1840s. We have the sentimentality of the serpent with its eternal love, the deep black of mourning in the enamel and the diamonds classifying fearlessness, strength and love. All these work in harmony to encapsulate the love of Vane, a love which is easily identified today. When combined with his final resting place, the person of William Harry Vane creates a personality in the ring; his very face in repose is reflected, once seen in his marble tomb, upon the ring.