White Enamel Mourning Ring for Wm Benham ob 30 Apr 1796 aet 23

When the young die, they leave behind a lasting imprint on the memory of a family. Their impact was felt for a short time and all the legacy that a parent would imbue upon a child is lost, effectively cutting the family history and removing a legacy.

1796 was an interesting year in mourning jewellery. For the past thirty years, the Neoclassical symbolism had evolved enough to become personal statements, even though the allegorical elements remained intact. To this end, the male in mourning depictions were used, but this was concurrent with male portrait miniatures, as well as sentimental allegorical depictions, which showcased men and women in classical garments, posed in ways that generally were sentimental in their intent. These pieces were painted on ivory and rather large with the miniatures kept in closed compacts. The nature of many mourning jewels in larger format were that they could be carried during travel and safe for reflection of the person who was carrying it.

The female was the ideal of the human condition when it came to representing a feeling. The lady, standing next to a tomb or plinth, was the concept of grief and the value that was seen as the ideal of mourning, regardless of a male or female wearing the token. In this particular ring, there is more of a snapshot into the 1796 period. The male sitting next to the urn, in obvious extreme perspective, as the urn’s large size dwarfs the gentleman. This only goes to add value to the sentiment of how loved the departed child was, even at the age of 23.

This is the depiction of a male in mourning, wearing the finest quality fashion, from the powdered wig, frock coat, breeches and holding the handkerchief to his face. It speaks to more of a sentimental portrait of a gentleman in mourning, rather than an allegorical figure. An allegorical figure would be dressed in Roman or Grecian robes, while this figure is fashionable. This ring would not have necessarily been worn for the daily use of its mourning sentiment, but a keepsake of the child, hence why it is in such fine condition.

But why is this ring so important as a mourning jewel? White enamelled jewels are rare, due to their sentiment. The white enamel is emblematic of youth, being a child or an unmarried person. It speaks to virginity and purity, which the white enamel is, as it is unblemished as a colour. Used in mourning, white is a colour that was originally more popular in fashion as a primary colour for mourning, which more can be read about in the following article:

Link > Mourning Jewellery in White

What makes this rather special is that the band itself follows on from the navette shape in the white enamel, making it a perfect ring for its time. Many of these pieces have been adapted from brooches into rings, which can be seen by obvious joins. These ‘marriages’ aren’t always easy to spot, but this ring captures every element through the band, which is something adapted from its previous century. Mourning bands generally capture the name and date of death of the deceased, which were the custom element in mourning rings, rather than the bezels. Bezels were generally pre-designed, even in the c.1680-1900 period. The crisp, white enamel still remains along the shoulders and through the ring, making it a superior jewel that encapsulates the level of expense and love that the person who commissioned this infused within the ring.

In this following ring, dedicated “Nat. 4th My 1785 Obt. 12th July 1789”, the politics of the world would have begun to influence the design of jewellery and its manufacture. To understand the nature of the Benham ring, further investigation into the 1790s and its symbolism are necessary.

In 1789, the French Terror introduced a level of panic into the broader European culture, which lasted to 1793, destabilising much of the economies that could produce fashionable jewels Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

The 1790s were an interesting time for people, and families, in general. With economic change, growth and instability, increased spending on fashion the arts and travel influenced personal status. Changing fashions from Europe, particularly France, were adopted into England, making Neoclassical jewels creations of what designs were aspirational. Materials that could be displayed denoted personal wealth and the latest designs changed rapidly. By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles was enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security, if fleeing the country.

Condensing the family into the depiction of a scenario within a jewel was a perfect way of capturing a realistic element of an item that could be worn and displayed. A status symbol in England was still part of adhering to society and the aristocracy through a social system that values monetary income.

The 1796 period should be focused on for its use of enamels and its investigation into other shapes and styles. Of note in this contemporary ring is the shank, which has the duel banding (two forks that reach the bezel) in the Gothic Revival style, as can be seen in the floral/acanthus embellishments. On top, the round shape was influenced by the 1760s, but grew into the rectangular shapes of the early 1800s (more of that can be seen in this article). Noteworthy is the use of enamel. White and blue enamel come together in this ring, for S King, the royal blue meaning for one to be considered royalty and the white to be the unmarried/virginal purity. It is a liberal use of the colours, being flanked by the pearls, which make it important that these colours were popular in colour theory in fashion for their day. They weren’t curiosities. Much like the William Benham ring that is the topic of this article, the use of colour in enamel is important as a factor during the 1790 period.

NOT LOST BUT GONE BEFORE

“The number of his children was the same as before : some say his children were dead, were not lost but gone before to a better world : and therefore if he have the same number of them, they may be reckoned as doubled.” – The Death of Job / An Exposition of the Old and New Testaments: Wherein Each Chapter is Preceded by an Analysis of Its Contents, the Sense Given and Largely Illustrated ; with Practical Remarks and Observations, Volume 2, 1833

“Not Lost But Gone Before” tends to be one of the memorial statements that became popular during the Neoclassical period for interesting reasons. The Bible was still the primary text in an Anglican environment, regardless of the classical Roman/Greco values that were popular during the time. Despite the Protestant/Catholic split, the values to the Christian God were still there and though the Enlightenment challenged things, the values remained the same. “Not Lost But Gone Before” was used for the ecclesiastical sense as well as that of the literal sense of someone passing away before their time. Of note, this particular jewel:

Shows the setting is in a church-yard cemetery with the headstones strewn across the ground. The physical setting of the jewel is actually contrary to the Neoclassical style that would be depicted in a jewel like this, as seen in the primary jewel in this article. There is no allegory, simply fact.

The 1790s had a fascination with the mourning dedications, interchanging them with Bible quotes and classical sentiments. In the above brooch, you can see the use of the ‘NOT LOST BUT GONE BEFORE’ phrase crudely written around the top of the oval shape. These dedications were typically customised for the person who commissioned the jewel, hence they were not perfectly balanced in the design. The rest of the jewel would be predesigned and painted, so that the person who selected the piece could quickly purchase and individualise the jewel as a mourning keepsake.

Urn

As part of the dual symbolism that this ring encapsulates, the urn is the primary focus for representing the body. It is a way to capture the remains of the body and a classical affectation used in modernity that was understood for its mourning purposes. The urn itself is a vessel, or more specifically a vase, which naturally have their beginnings in pre-history when humanity began gathering items in order to carry them. We won’t be dwelling on this form of history, but rather the ancient Greek use of the urn in artistic depictions. The urn itself had evolved as a decorative item, often with art displayed upon the vessel itself prior to Greece in neighbouring Mediterranean societies, but its interpretation in jewellery design stems mostly from the Greek and Roman scenes in art and their reinvention during the Neoclassical period.

Usage of the urn had never wavered, however. Cremation of the body and the collection of ashes in the urn is a method that survived ancient civilisations well into the Dark Ages. The name itself is derived from the Latin ‘uro’, meaning ‘to burn’, so no matter what the shape of the vessel the title was always ‘urn’. This is a concept that never left the mainstream mind and its uptake as a Neoclassical symbol and its consistency as a funerary motif is simply a natural evolution for the urn’s depictions.

While burial became the more popular method of interment, the urn still retained its status as a symbol of death, testifying the death/decay of the body and into dust and the departed spirit resting with god.

Draped urns are another variation of the popular symbol in the Neoclassical period. The draped urn itself often denotes the death of an older person, however, the drapery is often a constant when in relation to death. Interpretations of this can be when the shroud drapery denotes the departure of the soul towards heaven in relation to the shroud over the body, the drape is the partition between life and death or that it is guarding the sacred contents of the urn itself. In jewellery, finding the urn draped or undraped is quite common, but why is it so?

The urn is a motif that reached incredible heights of popularity in Neoclassicism due to its interpretation from the original classical depictions. It was a motif that was easily lifted from its source and fulfilled all the classical resonance that a revival period needed to convey the style of its respective era. With the focus back upon the personal nature of mourning and the departure of the direct link towards god, death itself became something worn prominently in mainstream fashion. The urn was a perfect way to show this, draped or undraped. Sitting on top of a plinth, column or tomb, the urn is often the central focus of the mourning depiction. The mourning character in the depiction (male or female) is often interacting with the urn in some way, either leaning against it weeping, sitting near it, standing beside it or looking at it directly. This links the personal nature of mourning from the person into the jewel itself. The mourner is the wearer or the person who created the dedication and the urn represents the loved one. Consider that; there’s a direct link in methodology of the urn to the self, this is why the urn is the central motif and not the mourner.

Consider that when looking at a brooch, ring, bracelet clasp, pendant or any other peripheral from the late 18th to early 19th centuries. The urn is the concept that should draw the eye and take precedence over everything else.

The symbol disappeared soon after the first quarter 19th century in mourning jewels, but was retained within funerary art. The Gothic Revival period played a key role in reverting society back to more ‘traditional’ values. Using a direct relation to the body in the urn conflicts with the burial/god connection which was part of the social understanding of life and death, that Christian values returned to a life under god.

You can find the urn in use to around the 1820s, but many of the latter uses in jewels are anachronistic in the same way that memento mori would have been during the late 18th century. However, in funerary, the urn was still retained and is to this very day. In fact, its use in architecture in the latter 19th century / early 20th century was quite typical, but it had largely disappeared as a motif to represent the self in mourning.

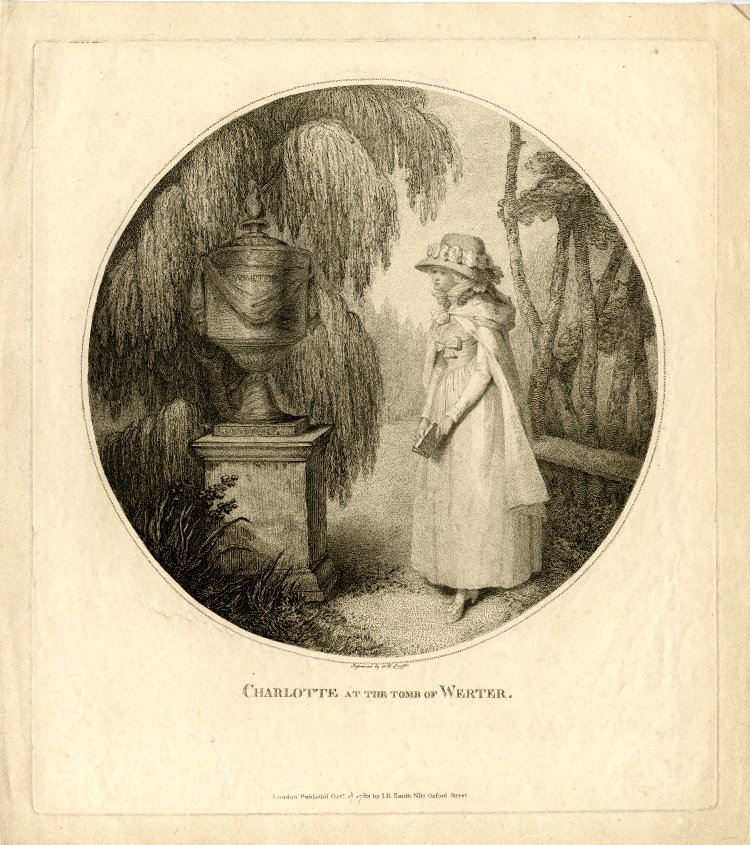

Popular culture was intrinsic to the rise of fashion and art in the 18th century. As previously seen in the Handel jewel, elements of mourning cross-pollinated from literature, music, art and fashion into jewellery design. In the above stoneware with blue jasper dip and applied white stoneware relief, the ‘tomb of Werther’ was based in popular culture. Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787 was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow and urn here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

Access to wealth, styles that could traverse continents and a younger generation growing up in this society all affected Neoclassical jewels. the symbolic value of a mourning jewel still retains its intrinsic elements of grief, but they go beyond this into the affectation of fashion. Simple grief is not enough in a period of increasing personal human interest, the fashion of it is required to present back into society and promote the status of the individual. In the 1780s, this reached new heights, creating the basis for the more necessary mourning jewels that would be employed during the European destabilisation of the 1790s.

Willow

The weeping willow is heavily symbolic of grief, sorrow and mourning, even physically, it stands as an analogy to human grief, with its back bent over the subject, be it a weeping figure, a tomb, plinth or any other mourning subject. Used in this ring, it is the second most important symbol which starkly stands out from the back background of the carved onyx. How did the willow get to be so popular and what were its roots?

“Though the Weeping Willow is commonly planted in burial grounds both in China and in Turkey, its tearful symbolism has been mainly recognized in modern times, and among Christian peoples. As has been well said: “The Cypress was long considered as the appropriate ornament of the cemetery; but its gloomy shade among the tombs, and its thick, heavy foliage of the darkest green, inspire only depressing thoughts, and present death under its most appalling image, whilst the Weeping Willow, on the contrary, rather conveys a picture of the grief felt for the loss of the departed than of the darkness of the grave. Its light and elegant foliage flows like the disheveled hair and graceful drapery of a sculptured mourner over a sepulchral urn, and conveys those soothing, though melancholy reflections…”

So, where can one find this in jewellery? Quite commonly, it became one of the most used symbols of the Neoclassical period, so look for it on miniatures set into bracelets, pendants, etc and to a lesser extent was used in the 19th century. It can still be found in cemeteries and on peripheral funeralia today.

1790s

The 1790s are best known for their use of the ‘navette’ shape, where the love token’s placement is within a shape that had a tall north-to-south area. This style was most typically used in bracelet clasps, rings and pendants. As an accompaniment to this, the popularity of the miniature portrait used an oval shape with an ivory disc inside to provide keepsakes, often at a higher quality. Miniaturist schools grew with the investment of new wealth, allowing for an increase in miniaturists and the availability for miniatures not to be just accessible to the aristocracy and monarchy.

The 1790s were about refinement and production. The earlier displayed styles did not disappear, they simply evolved. The design of the female, urn, willow and all peripherals were perfected to the point of standardisation. The ‘navette’ shape was the perfect standard size to have the willow flank its border and the central element, be it the tomb or urn, were on display as the focus of the jewel. Larger miniature styles could be carried in compact cases and carried with the individual, or displayed in the home as required. As can be seen in the above ring from 1791, this sepia painting is the standard for mourning elements in the late 18th century. The willow, urn and plinth are all standard, painted on ivory and show the tall north-to-south navette shape. A ring like this could be purchased, with the reverse engraving being made at the time of commission.

Construction methods still underwent experimentation in the 1790s, but there was more of a template to work from. This urn ring from 1791 is enamelled in black and features the urn as the central element of symbolism. The hoop with shoulders and bezel form two hands grasping at the urn, which is hinged to reveal a locket fitting for hair. It is engraved inside with initials ‘MP’, a London hallmark for 1791-92 and maker’s mark ‘WK’., England, 1791-2. Use of the locket in a ring was being experimented with through the turn of the 19th century and would continue to be one of the more popular designs during the 19th century. The giving of hair as a symbolic gesture, be it alive or dead, was amplified by Queen Victoria and moved hair from being a more hidden element to the prominent focus of the jewel. For the 1790s, this ring is a perfect representation of sentimentality in mourning, with the addition of the hands, it amplifies the symbolic message.

In the above pendant, the use of pearl and ivory creates the mourning scenario, which is far more esoteric than the standard. Value of the jewel could scale higher or lower, allowing for greater detail in the more affluent pieces. The inscription is ‘Henry Halsey Inft. aged 10 Mos. died 12th Jan 1798.’ and ‘Fond Parents grieve not for thy Infant Son Your God has called him and his Will be done.’ Pieces for children and the use of white in enamel, have more immediacy to their design and requirement. Sudden deaths have less time to plan for, as burial societies would be paid a year on year fee to cater for the burial and its peripherals, children did not have that luxury.

At the end of the century, larger styles displayed highly detailed miniatures. The classical figure was designed and could be tailored to the individual. Typically, it is the sentiment that was tailored, often seen in the change in design of the wording to the art of the piece. Set in gilt copper, this sepia-painted on ivory brooch shows the women beneath the willow, mourning at the urn and plinth, inscribed with ‘Sacred to the Memory of Dear Parents’. Dimension is an important factor in 1790s mourning miniatures, as there is a greater allowance for detail and depth of perspective. Note the detail to the painting underneath the glass, which pushes a foreground and background effect to the miniature work. Pre-designed styles like there were typical from the 1780s to the 1820s, with travelling miniaturists having the ivory discs painted and amended upon purchase. With Neoclassical styles having an idyllic depiction of the facial features, even miniatures of individuals could be tailored in hair and eye colour.

Colour is another element that the 1790s are popular for using. The sepia tones, denoting the body and the earth, were the popular mourning standard, but painted colour was used more frequently in the 1790s. It added another element to the mourning standard, as seen in the above locket. This jewel is an enamelled gold frame enclosing a painted miniature, embellished with ivory, gold foil and hair, of a woman seated by a column and a angel pointing to a label inscribed ‘Weep not, it falls to rise again’.It is all in high relief and represents the pinnacle of the 18th century, when the allegory begins to eclipse the actual person in mourning.

End of the Century

The 1790s held great destabilisation for Europe, removing much of the focus of power from systems of government and putting them upon the individual. From America succeeding to the French Revolution and global colonisation, traditional systems of power were struggling to maintain consistent identity that a public could identify with. Mourning, as a fashion, is intrinsically personal and about the self. Having an identity in mourning is as important to a culture, as the visibility of the person in mourning represents the family and its ideals. With these ideals, religion and government follow.

Having a distinct language in mourning fashion could identify a culture around the world, with people bringing their own traditions and values with them as transit and colonisation increased. The late 18th century was the inception for what these symbols of death would be throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as the art was replicated in cemeteries and funerary art. The global standard is reflected in the jewels, from the urn and willow to the female mourner, they are as timeless as the Greco-Roman world they are trying to reference.

A ring made for someone at the age of twenty three resonates with the same empathy and love that it had then. It’s hard to not look at this ring and think of the person who passed on, or the person who commissioned it. The white enamel is pristine, the depiction is personal and someone genuinely felt the love for William Benham then as anyone would now for a loved one. When seen through the lens of the historical symbols, the ring only becomes more powerful, with the urn and the willow dominated the space, yet the person in mourning is sitting there in his grief, flanked by those symbols. This is an important jewel in history, as it allows us to go back in time to the 18th century and these artefacts will live on to make us appreciate just how fragile we all truly are.

Courtesy: The Museum of Love and Mortality (Marielle Soni), Laura Masselos, The V&A Museum