Tulip Symbolism in Jewels

The Museum of Whitby Jet is a genuine establishment of living history. Combined with the store W. Hamond, it presents the oldest connection to 19th century Whitby Jet manufacture that still exists. It is a tribute to the 1500 men and 200 shops that existed in 1873 to produce the finest quality of Jet available in the world. Their craft, of carving, turning and polishing jet held a standard that set the British Empire beyond any other jet industry in the world, being held in the highest regard by Queen Victoria herself.

Due to the popularity of Whitby Jet, the instances of its carving designs are almost infinite. The Victorians relished the romantic and sentimental language of flowers. They were educated, had access to new wealth and were the first affluent middle class that could afford leisure time. Travel was a part of seasonal Victorian lifestyle and cottage industries emerged with the connection of rail lines that ferried these sentimental people across Britain. Whitby’s popularity as the centre of Jet fed its local community and its economy. Carvers were charged with appealing to the most popular designs from the visitors, who requested sentimental tokens to gift to their loved ones.

This Art of Mourning series is in partnership with the Museum of Whitby Jet and is a look at the jewels of the museum through the eyes of the Victorians who requested and understood the love language of flowers.

To achieve this, part 1 of the series is an introduction to Whitby Jet, which can be read below:

Link > Discover Whitby Jet

Part 2 is an understanding of ‘floriography’, a late 18th and 19th century attempt by philosophers and writers to connect floral discoveries of the world to emotion to empirical fact. This can be read below:

Link > Understanding Symbolism: Botany and Floriography

Symbolism of The Tulip

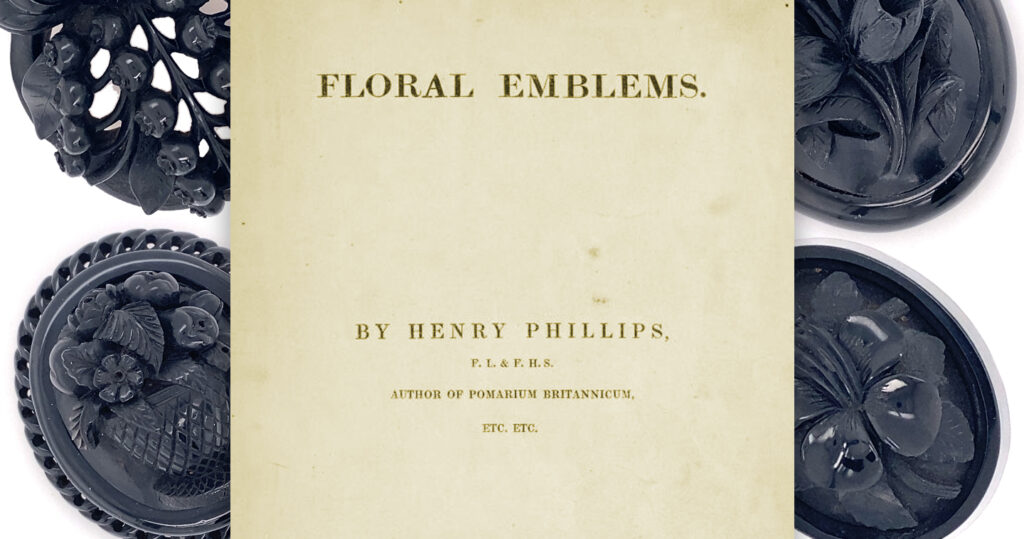

Cultivated in Turkey c.1000 CE, the tulip is a popular symbol for the declaration of love. The botanist, Carolus Clusius, introduced the tulip to Europe in the 16th century and its popularity led to the association of it with The Netherlands, with their cultivation there leading towards massive revenue for the region. Tulips were associated with the Persians in floriography, as their sentimental connection between lovers. In Floral Emblems (1825), Phillips wrote that “The tulip has from time immemorial been made the emblem by which a young Persian makes a declaration of love… Chardin tells us, that when a Persianare sent a tulip to his mistress, it is his intention to convey to her this idea,’that like this flower, he has a countenance all on fire, and a heart reduced to a coal.”

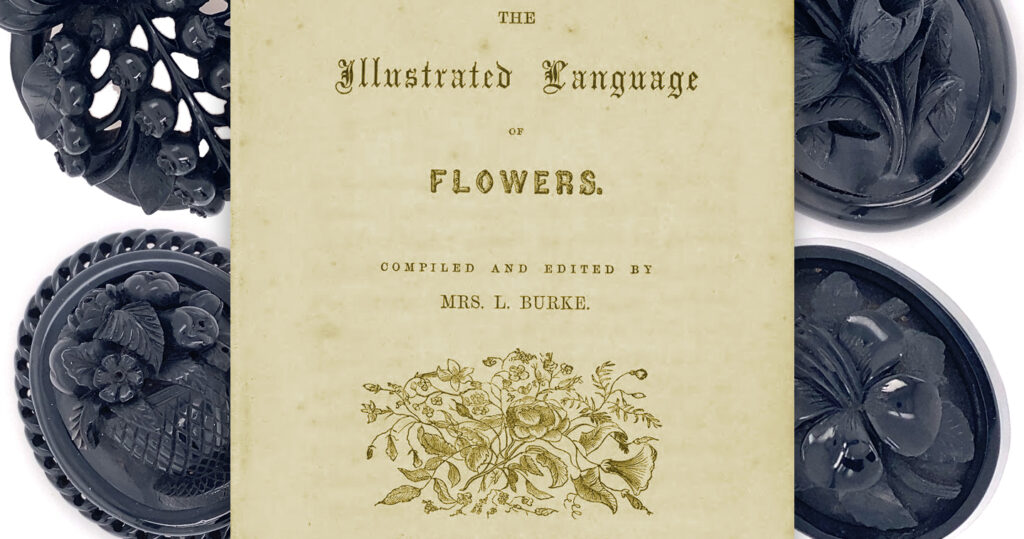

Tulip design was used across a variety of Victorian sentimental jewels in all its colours. Burke’s Illustrated Language of Flowers (1856) outlines the meaning of its colours as:

Tulip, red… Declaration of love.

Tulip, Variegated… Beautiful eyes.

Tulip, Yellow… hopeless love.

The Tulip’s connection to the emotional values of giving the self in the hope of love is intrinsic as to why it was given to a loved one as a sentimental jewel.

DECLARATION OF LOVE. Tulip.— Tulipa.

“ Then comes the tulip race, where beauty plays

Her idle freaks.”

Thompson .

• There’s fairy tulips in the east,

The garden of the sun ;

The very streams reflect the hues,

And blossom as they run.”

Wiffen.

The tulip has from time immemorial been made the emblem by which a young Persian makes a declaration of love.

Chardin tells us, that when a Persianare sent a tulip to his mistress, it is his intention to convey to her this idea,’that like this flower, he has a countenance all on fire, and a heart reduced to a coal.

“Good Shepherd, tell this youth what

’tis to love. It is to be made all of sighs and tears;

It is to be made all of faith and service;

It is to be made all of fantasy,

All made of passion, all made of wishes; All adoration, duty and obedience ;

All humbleness, all patience, all impatience,

All purity, all trial, all observance.

Shakespeare.

Floral Emblems, p. 112 – 113

TULIP.

DECLARATION OF LOVE

In the East, the Tulip is employed as the emblem by which a lover makes a declaration of love, presenting the idea that, like that flower, he has a face all on fire and a heart reduced to a coal :-

Whose leaves, with their ruby glow,

Hide the heart that lies burning and black below.

On account of the elegance of its form, the beauty of its colours, but its want of fragrance and other useful qualities, this flower has been considered as an appropriate symbol of a female who possess no other recommendation than personal charms.

It is supposed to have been brought from Persia to the Levant, and it was introduced into Western Europe about the middle of the sixteenth century, by Busbeck, ambassador from the Emperor of Germany to the Porte ; who, to his astonishment, found Tulips on the road between Adrianople and Constantinople, blooming in the middle of winter, intermingled with the hyacinth and the narcissus, and could not sufficiently admire their beauty. The name given to it by Europeans is supposed to originate in a corruption of the Persian word for dulbend, the muslin head-covering adopted by the Mahometan nations, which we have transformed into turban. In a Persian of rank this article of dress in not unlike the swelling form of the Tulip. Moore, in his “Veiled Prophet,” alludes to this resemblance :

What triumph crowds the rich Divan to-day

With turban’d heads of every hue and race,

Bowing before that veil’d and awful face.

Like tulip-beds of different shape and dyes,

Bending beneath th’ invisible west wind’s sighs !

On their first introduction into Europe, Tulips became especial favourites of the cultivators of flowers. From Vienna they soon spread into Italy, and were sent in 1600 to England. Eleven years later they were first seen in France, in the garden of the learned Pieresc, at Aix, in Provence. In Holland, about the middle of the seventeenth century, a real mania for possessing rare sorts seized all classes of persons. It would be almost impassible to credit the extraordinary accounts of the high prices given in that country for Tulips, did we not know that it was a rage for gambling speculations, rather than a fondness for flowers, which occasioned these excesses. For a single Tulip, to which the Dutch florists had given the fine name of Semper Augustus, were given four thousand six hundred florins (about £400,) a beautiful new carriage, a pair of horses, and harness : another of the same kind sold for thirteen thousand florins ; and engagements to the amount of £5000 were made during the height of this mania for a single root of a particular sort.

A person who possessed a Tulip of a very fine variety, hearing that there was another of the same kind at Haarlem, repaired to that city, and having purchased it at an enormous price, placed it on a stone and crushed it to a mummy with his foot, exclaiming with the exultation, “Now, my Tulip is unique!” We are also told that another who possessed a yearly income of sixty thousand florins, reduced himself to beggary in the short space of four months, by purchasing these flowers. From this spirit of floral gambling the city of Haarlem is said to have derived not less than ten millions sterling in the space of three years !

It is related that, during the prevalence of this mania, a sailor, having brought some goods to a merchant who cultivated Tulips on speculation, had a herring given to him for his breakfast, with which he walked away. As he passed through the garden, he saw some roots lying there, and mistaking them for onions, he picked them up and ate them with his herring. At this moment, the merchant, coming forward and discovering what had happened, exclaimed in despair, “Inconsiderate man, thou hast ruined me with thy breakfast! I could have regaled a king with it.”

If we may believe these recent accounts, this fondness for Tulips still prevails in Holland to such a degree that a sum equal to £640 was lately paid by Mr. Vandernick, a florist of Amsterdam, formerly a captain in the Dutch navy, for the bulb of a new species called “The Citadel of Antwerp.”

From the extraordinary favour thus shown to the Tulip, the species were soon multiplied to such a degree, that in 1740, the Baden-Durlach garden at Carlsruhe contained not fewer than two thousand one hundred and fifty -nine sorts; and the garden of Count Pappenheim boasted at one time of five thousand varieties.

The estimation in which the Turks still hold Tulips is little inferior to that which they formerly enjoyed in Holland. They are never tired of admiring its elegant stem, the beautiful vase which crowns it, with the streaks of gold, silver, purple, red, and the innumerable tints which revel, unite, and part again, on the surface of those rich petals.

And sure more lovely to behold

Might nothing meet the wistful eye,

Than crimson fading into gold

In streaks of fairest symmetry.

LANGHORN.

The bulb or root of the Tulip resembles in every respect the bug of other plants, except being produced under ground, and includes the leaves and flowers in miniature, which are to be expanded in the ensuring spring. By the careful dissection of a Tulip-root, and cautiously cutting through its concentric coats, lengthwise from top to bottom, and taking them off successively, the whole flower of the next summer with all its parts may be discovered by the naked eye. A popular poet has alluded to this circumstance in these lines, written “On planting a Tulip-root :” –

Here lies a bulb, the child of earth,

Buried alive beneath the clod,

Ere long to spring by second birth,

A new and nobler work of God.

’Tis said that microscopic power

Might through his swaddling folds decry

The infant image of the flower,

Too exquisite to meet the eye.

This venal suns and rains will swell,

Till from its dark abode it peep,

Like Venus rising from her shell,

Amidst the spring-tide of the deep.

Two shapely leaves will first unfold ;

Then, on a smooth, elastic stem,

The vernal bud shall turn to gold,

And open in a diadem.

Not one of Flora’s brilliant race

A form more perfect can display ;

Art could not feign more simple grace,

Nor nature take a line away.

Yet, rich as morn of many a hue,

When flushing clouds through darkness strike.

The Tulip’s petal’s shine in dew,

All beautiful, but none alike.

MONTGOMERY.

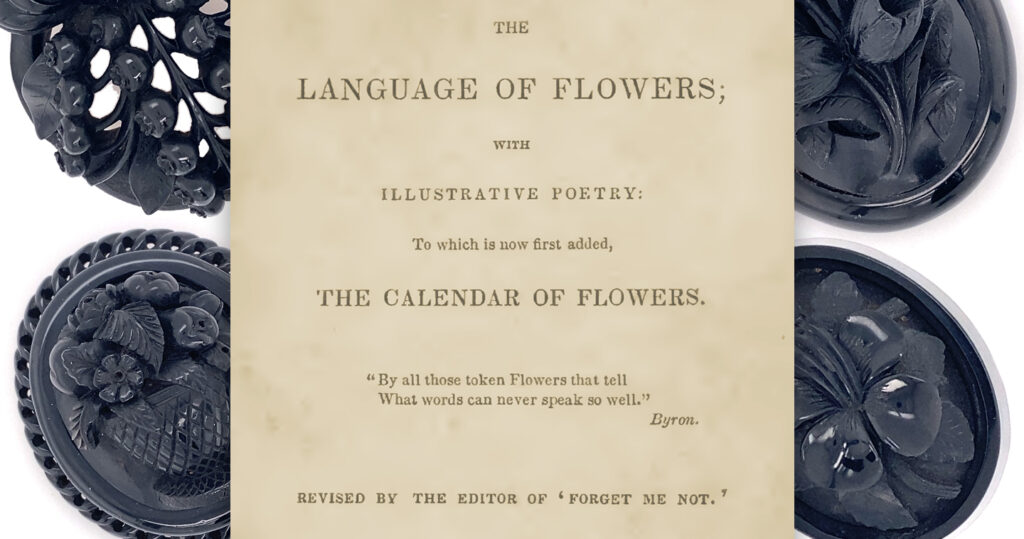

The Language of Flowers, p.75-80

TULIP – FAME .

Not one of Flora’s brilliant race

A form more perfect can display ;

Art could not feign more simple grace,

Nor Nature take a line away.

Yet, rich as morn of many hue,

When flashing clouds through darkness strike,

The Tulip’s petals shine in dew,

All beautiful, yet none alike.

MONTGOMERY

The Illustrated Language of Flowers p. 57

Tulip, red… Declaration of love.

Tulip, Variegated… Beautiful eyes.

Tulip, Yellow… hopeless love .

The Illustrated Language of Flowers, p.58