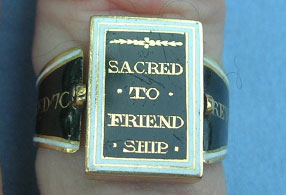

Sacred to Friendship – Discovering New Messages of Love in 1770

One of the key aspects of a love token is that it resonates a certain personality of its wearer. With so much attention given to how a relationship is established and how that is presented within society, the smallest symbol or piece of fashion can change the interpretation of how someone is perceived. This is especially important to note with mourning and sentimental jewels, particularly in their contemporary times. Understanding the society is just as important as the construction of the jewel, as these are complete symbolic metaphors for their status and interior feelings.

With this ring, a perfect balance of symbolism that was highly identifiable from the pre-Neoclassical Era is combined with the perfect classical symbols that had been re-appropriated through the Neoclassical movement. What would have been a collection of Memento Mori symbols containing elements such as the skull, crossbones, hourglass, scythe and putti/cherubs are now replaced with the allegorical symbols of the laurel wreath, the two hearts, the unbroken column and the dove.

In the use of the putti/cherub, we can see the connection between the earlier jewels and the newer, as this symbol was constantly in use, regardless of the romantic/humanist movements that were removing the ‘self’ from ecclesiastical domination. While these movements took away from the literal sense of judgement upon death, or the union of two people under the eyes of a God, the values still remained.

As can be seen in the above piece, the cherub is welcoming the soul of the deceased child to heaven. All the peripheral classical symbols that were appropriated from the Greco/Roman world, yet the monotheistic reference remains. In England, the installation of the monarch as a direct conduit to God in 1534 was still a relatively recent occurrence for the 1770s, which is when this ring would have been created. When the monarch is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England and there is a massive influx of Protestant emigration to Britain post 1686, the shift that came along with the Age of Enlightenment to welcome classical symbolism in jewels was welcome. Further to this, Protestants bought with them not only skills for jewellery construction, but also strengthened the values of Protestantism, allowing for jewels like this to exist in a society of changing values.

Sacred to Friendship

In the surrounding message of ‘Sacred to Friendship’, the intent of the ring is displayed. The friendship status of the piece denotes its loving aspect in a way of betrothal and a message to the wearer of undying love and fidelity. For its time, this message was one of the most prominent found in sentimental jewels and also for mourning jewels. Due to its statement, it doesn’t suggest a family attachment, but rather one of a growing relationship.

Friendship is a statement that was used in death (as in the above 1798 mourning ring), or for the purposes of offering love in life. The proximity of the relationship, be it parent/child/husband/wife) are common sentiments written into jewels for those specifically connected through those relationships, whereas a ring such as the focus of this article, is promoting overtures of love and fidelity through friendship.

In the above piece, a bespoke sentiment for the parents is written, which is directly customised by the person who commissioned it. The relationship value goes beyond any set friendship and impacts upon the values of the wearer. In the 1770s ring, being ‘sacred’ is what the friendship requires and this may even lead towards a greater bond and family creation.

Style in the 1770s

Previous to the Neoclassical style c.1765, jewellery styles were taken from the Rococo period which was embellished by nature in its design, a move away from the heavier Baroque elements which were straighter in shape.

The above 1761 ring is ideal for its time. All of its design elements, from the use of the acanthus leaf upon the shoulders to the incredibly detailed ribbon/twist which creates the band and its black enamel inlay define the times. As this ring was a mourning piece, the set style needed standardisation to be identified as a mourning ring and to be produced in high enough numbers that would satisfy the new wealth which could afford such jewels. From the wealth and faster production techniques developing from the Industrial Revolution at the turn of the 18th century, mourning and sentimental tokens became more of a requirement for social presentation, other than being simply a bequeathment in a will.

The 1770s took on the affectation of the Neoclassical Era, using all the motifs and elements in deign without any particular one style to define it. By the 1790s, this would be standardised, but in the 1770s, there was more of a raw interpretation of the classical symbolism to create a sentimental depiction.

To accommodate this, the first thing that needed to change was the way to display the sentimental depiction. Having a painting on ivory or vellum that would be worn required a better spatial area on a ring, pendant or bracelet clasp. In this ring, we can see the introduction of the oval shape to allow for this, a shape which did indeed adapt the style of previous jewels, as the Neoclassical symbols weren’t an instant cultural change.

Through the above ring, which was created in 1774, the style and construction is quite close to this ring. One major difference is the band itself, with this having rounded edges, while the above moss agate ring is flat.

Yet, with the amethysts surrounding the moss agate ring, the pearls surrounding the sepia ring are virtually the same in style.

Where it was mentioned that the previous styles of jewellery did not immediate stop post 1765, the following ring shows the adaption of the enamelled band in 17770 jewellery, with a straighter edge, but carrying the same detail:

Through this ring from 1777, the standardisation created in the Neoclassical Era was almost complete. As a template for a mourning jewel, it had all the elements in design which captured the symbolic sentimentality, the perfect balance of those motifs in a crisp design and the balance of this with the sentimental dedication.

Bird

The dove is commonly found in sentimental miniatures of the Neoclassical period and would often be seen being held, or sitting near two lovers? This is because the dove represents peace, love, purity and gentleness.

From an ecclesiastical standpoint, the dove represents the Holy Spirit, hence why it is quite commonly found in cemeteries of various Christian denominations. The white dove is referred to in the story of baptism of Christ. “And John bore record, saying, I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it abode upon him” (Bible, John 1:32). The descending dove is a very common motif on grave memorials. Seven doves are representative of the seven spirits of God or the Holy Spirit in its sevenfold gifts of grace. Purity, devotion, Divine Spirit. When shown with an Olive Sprig it means Hope or Promise.

It should be noted that the bird in relation to a sentimental image is also important; if the bird is a dove, then it can be further detached from the subject and more inclined towards a neo-classical ideal of peace/hope/heaven, if the bird a sparrow then love (dedication, trust), if the bird is a swallow, there’s motherhood or children involved. There are many neo-classical images of the woman holding the bird with a man looking upon her or involved with her (hand upon shoulder or body) which allude to motherhood, futurity and the prospect of a child. Many of these bird subjects often come back to the nature of the child.

Wreath

An interesting point to note is the use of the wreath and how early this piece was. The laurel wreath, denoting victory and redemption is being placed upon the hearts in classical style, honouring the love of their union. The sepia helps reflect the gold colour, which is another connection to its classical history.

In this piece from a decade later, when the Neoclassical movement had been fully engrained in the cultural psyche, the wreath is being placed by the dove, without the cherub, yet the elements are perfectly designed with the assurance that isn’t reflected within the sepia ring. From a design perspective, this element was used enough that a miniature painted could produce enough of these to sell to a growing consumer base without having to tailor its surrounding elements.

Column

The column as represents the strength of life, as it points towards the heavens and is usually (next to the image of a weeping woman) one of the most prominent symbols in a memorial / sentimental scene. In this case, there is the strong, proud object, seemingly timeless (eternity) and then you have a broken variation. That leads one to think that the life has been cut short early. Involved with this is also grief, decay and the concept of this strong central figure being broken can represent the loss of the patriarch / matriarch of the family.

An element of note is that the column isn’t as grand as other columns depicted within sentimental and memorial jewels. This piece was created during the introduction of the style, rather than having the proud column as the central focus, all design elements are crowding the ring to not have one central focal point. Due to this, it is a fascinating insight into how the classical elements were being interpreted during the latter 18th century in order to define which symbol made the clearest statement.

Cherub and Putti

Simple designs within sepia, or any form of painted Neoclassical jewel, can often suggest how bespoke it was. When jewels have very specific symbols that are very individual for the wearer and yet the painting is quite naive, then the painting is often commissioned or created closer to the home, relating to folk art. This is most prevalent in mourning/sentimental samplers, where the women of the household would learn stitch work and design woven samplers to commemorate an occasion for the family.

When the designs are more intricate, they can be either pre-made or bespoke, depending on the surrounding jewel and its materials, this can gauge the value of wealth and individuality that the piece has. With the design of the cherub, the painting is quite simple and correlates to other popular motifs at the time.

Many of the angels/cherubs depicted in sentimental jewels are often mistaken for Putto, as the depictions can often lack intricate detail and the relation becomes nebulous. This is particularly so in sentimental jewels and classical depictions, with heaven being an important factor in the soul’s departure to the afterlife. Putto derives from the Italian putus (boy/child) and was depicted in classical art as the child acting as a guide or a spirit. Donatello bought the putti back into the popular mind through his fusion of the putti with Christian symbolism. This combination effectively made the allowance of the classical meaning correct for sentimental depictions, as the ecclesiastical undercurrent still justified religious belief.

As the ‘messengers of God’, angels are commonly thought to fit into the paradigm of Judeo-Christian, which is quite acceptable, but their transcendence in art and their ubiquitous use (even through the less-overtly religious Neoclassical Era) is given to their focus as spiritual beings. Furthermore, their presence is a clear statement of the afterlife, protection and an acknowledgement of the spirit after death. From the earliest Christian depictions of the iconic ‘angel’ (with wings), angels became one of the more prominent foci of ecclesiastical art through to the early modern period of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. From this, the angel in memorial art is still used today, greatly connected to funeralia and its symbolism.

Two angels: Can be named, and are identified by the objects they carry: Michael, who bears a sword and Gabriel, who is depicted with a horn.

Blowing a trumpet: (or even two trumpets) representing the day of judgement, and Call to the Resurrection

Carrying the departed soul as a child in their arms, or as a Guardian embracing the dead. The “messengers of god” are often shown escorting the deceased to heaven.

Flying Angel: Rebirth

Many angels gathered together in the clouds: represents heaven.

Weeping: Grief, or mourning an untimely death.

Within the character design of the face and the body, the 1770 ring shows the influences of wealth and design standardisation. The design to the face and the body are simple, yet convey all the correct detail for its size. Many of the oval-shaped bezel rings in the 1770s were quite small, around 1-2 centimetres in circumference, hence it was quite difficult to paint in high detail for a highly-produced item at a reasonable cost.

Compared to the 1792 ring seen above, the figure is clear and defined. Of note, it is the shape of the navette ring, with the large north-south design which could allow for more detail in the characters and scenario. For a ring that is roughly two decades away from the 1770s piece, classical symbolism had become standardised in modernity.

Pearls

Discovery and trade led to the desirability of pearls, particularly from medieval and Elizabethan times. ‘Oriental’ pearls, originating from the oyster family, were the most desirable due to their lustre, which pearls from freshwater mussels and conch shells do not have. The Oriental pearls were bought to Europe form the Persian Gulf by caravan traders.

The popularity of pearls reached their height in the late Georgian Era, where clusters of seed pearls were sewn to mother-of-pearl backs with cat gut, some examples can be seen below from the British Museum:

“Oval gold brooch with seed-pearls, in the form of a winged cupid with a lamb, on a base of mother-of-pearl, gesso or plaster; laid onto a background of blue enamel or blue glass and set under a domed glass cover in a gold mount within a pearl border. Inscribed in French.”

“Marquise-shaped pendant with seed-pearls, in the form of sheep and lambs under a tree, on a base of mother-of-pearl, gesso or plaster laid onto a background of blue enamel or blue glass and set under a domed glass cover in a gold mount with blue and white enamel and a tooled gold border. Compartment on reverse with plaited hair under glass.”

“Gold finger-ring with seed-pearls, in the form of a spray of flowers, on a base of mother-of-pearl, gesso or plaster; laid onto a background of blue enamel or blue glass under a domed glass cover in a gold mounted oval-shaped bezel with a pearl border.”

“Marquise-shaped pendant with seed-pearls, in the form of two birds carrying a knotted ribbon, flowers and wheat-ears, on a base of mother-of-pearl, gesso or plaster, laid onto a background of blue enamel or blue glass and set under a domed glass cover in a silver mount with a gold backing, with a border of pastes set in silver and a tooled gold inner rim.”

Many of these are only 10-20 years later than when this ring was created and shows the immense popularity of pearls and their decoration as status. With the increase in new wealth and greater methods of continental transit, the acquisition of pearls was faster and cheaper than it had previously been and this ring lays the groundworks for what was to come.

Eternal Love

A combination of all these elements makes for one of the most beautiful and sentimental rings which a loved one could give. For its time, this is a ring which speaks to a new style and a new identity of presenting love within society through symbolism. A dove, a wreath, a column, two hearts and a cherub with seed pearls, all denoting purity, victory, devotion, redemption, union of love and eternity all spoken without any more words than ’Sacred to Friendship’.

While much of its identity may not be as obvious to a modern audience, its history is classical and its message will live through the ages.