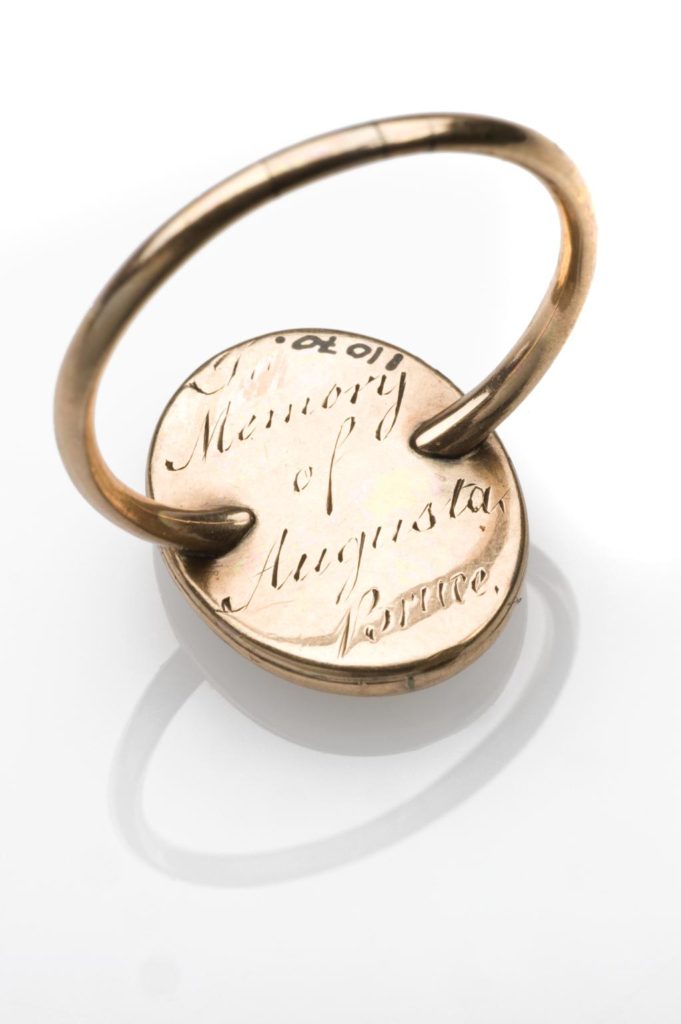

‘Nipt in the Bud’

‘Nipt in the bud’, seen in this ring from the c.1780s, shows all the elements of its time. The very thin bezel and the high detail to the sepia painting shows little conformity and a lot of personal sentiment in what was offered to the person who commissioned it. Augusta Bruce passed away during the latter 18th century and someone commissioned this ring to be made for her. Why the rose? Further investigation is needed into the history of its symbolism to discover more.

The rose is a symbol of love; a given rose to a loved one, suggests that the person is beautiful, that there is unfailing love and hope. A cabbage rose is considered to be an ‘ambassador of love’, while a white rose represents ‘I am worthy of you’.

The red rose, however, is a more unusual one. The red rose is the most popular colour given and has several meanings. The red colour itself denotes passion, with an association to Venus (love, fertility and beauty) in Roman mythology. In Greek mythology, Aphrodite is said to have named the flower, while Chloris, the goddess of flowers and a nymph of the Island of the Blessed, created it. As the mythology is explained, Chloris was wandering through the wilderness, when the beautiful corpse of a nymph was discovered among the bushes. Chrlois, being herself a nymph who did enjoy flowers, growth and Spring, turned this corpse into a flower. Aphrodite bestowed beauty upon the flower, Dionysus offered a sweet scent, Zephyr pushed aside the clouds with a mighty West Wind and Apollo shone down all the power of the sun to make the rose bloom. Eros has also been associated with the rose (silence), leading into the phrase ‘sub rosa’ (under the rose / to keep a secret) which was established with the Romans placing a wild rose on the door where secret discussions were underway. Secrecy, love, beauty and passion (regardless of what the passion may be referring to) are all part of the symbol’s meaning.

c.1230, the appearance of the poem “Le Roman de la Rose” appeared, itself using the rose as the name of the protagonist and the symbol of female sexuality. For its time this French allegory was considered quite controversial at the height of the Middle Ages. It was translated to from Old French to English as ‘The Romaunt of the Rose’ and consistently retold.

As a Christian symbol, the red rose is adopted as the presenting the blood of the Christian martyrs. The Virgin Mary is associated with the white rose, hence its relation to purity, virginity and innocence. Notice from this the same relation to white enamel and its application to memorial jewels. As legend would have it, the rose grew in Paradise and did not have a single thorn upon its stem. Adam and Eve were were expelled from Eden, yet the beautiful nature of the rose remained, but the thorns appeared to remind us all of our lost paradise.

The Virgin Mary, being without the original sin, is referred to as the ‘rose without thorns’ for this very reason. Indeed, the five petals have been likened to the five wounds upon Christ.

For mortality purposes, an understanding of the rose is necessary. If the rose is a bud or flower, this will denote the age of the person at time of death and is especially important when viewing Neoclassical pieces. If the flower is a bud, then you will find the age to be often twelve years or younger.

If in partial bloom, a teenager, full bloom in the early or mid-twenties. Particularly this is important as this is considered the ‘prime of life’, though for times with higher mortality rates, those who made it beyond might have various other symbols to denote long life. The broken rosebud relates back to the young person again, this time with a life cut short.

If rosebuds are joining, then there is a strong bond between two people, such as a mother and child who may have passed at the same time. The rosette is reserved for the Lord, messianic hope, promise and love (note the religious addition to the more personal reasons for the rose symbolism of love).

The wreath of the rose is beauty and virtue rewarded, connecting to other forms of floral wreath and garland. A more modern approach to the colours of the roses are the colours being identified as dark pink; gratitude/appreciation, light pink; admiration/sympathy, white; reverence/humility, yellow; joy/gladness/friendship and black; death.

Like most floral motifs and Romantic concept that we accept as being ancient in this age, we have the 19th century to thank for many of our perceptions and values. The rose became heavily cultivated with the introduction of the evergreen China rose in the 19th century, but there was a high degree of interest in the flower during the 18th century. The red/white rose had previously become the symbol of the House of Tudor (Henry VII – Elizabeth I), adopted after the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. This was the finish of the War(s) of the Roses, between the House of York, which had the white rose and the House of Lancaster, which had the red. As it was united, the Tudor Rose became the symbol of England. It should be noted that the national flower of the United States is also the rose.

Where will we see the rose in early modern jewellery history, specifically mourning and sentimental jewels? Much of the use of the rose is in relation to the popular art of the time. We must look at the 17th century as the best place to start. Here, we have the Baroque motifs merging with the mainstream memento mori motifs, which would later be adopted by the Rococo. Whilst it would be most common to find the skull, crossbones, scythe, hourglass, angels and death figures set under faceted crystal, the other side to this was the popularity in personal initials set with gold wire and balanced with other motifs. From this, the rose (often a personal statement or in relation to a family coat of arms) could be depicted. As well as this, the earlier mentioned Baroque gold-work with heavy natural flourishes often involved a multitude of flora in decoration, which is where you might also spot a rose.

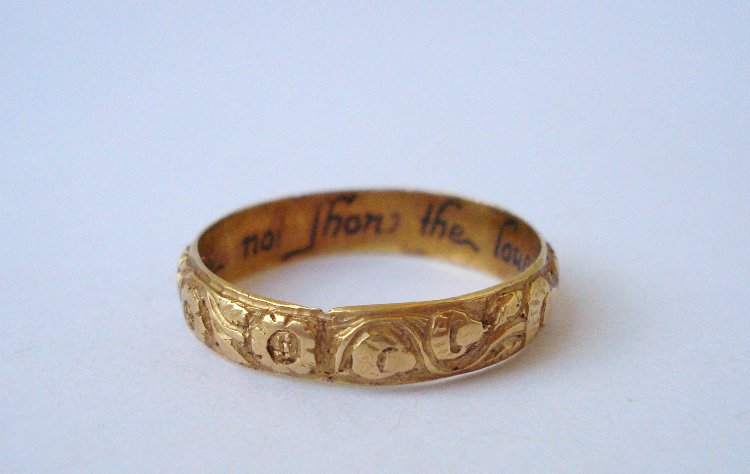

Note earlier how the rose was taking connotations for love and female sexuality c.13th century. Consider this with posy rings popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. Personal motifs and sentiments hidden inside a ring. Once again, the ‘sub rosa’ concept of keeping secret, yet retaining that passion comes into play. Much like with the forget-me-not, the rose can be found inside (and sometimes outside) of the posy band as a decoration.

Moving into the Neoclassical era of c.1760-1820, we can find the rose as a secondary motif in memorial and sentimental depictions. Often in sentiment depictions, the rose would be a motif given between a scene of two lovers. In mourning depictions, we have to look at the above connotations of what the rose means in terms of age and placement. If at the feet of the tomb or the mourner, one must consider the rose as a life cut short, yet still retaining that loving aspect discussed.

By the 19th century, the influx of various styles that captured and morphed the views of the natural world into mainstream art all captured the rose to some degree.

The Gothic Revival period was quite strong on simplicity and boldness in the presentation of the mourning subject, without the excess of the Neoclassical depictions. Big, bold enamelwork was typical, however, the period did take into account the heavy Baroque borders in much of the gold-work from 1830-1840s, which is where the rose will be in these forms of jewellery. As a motif on its own, the rose was not a mourning sentiment that grew beyond the physical grave and it was a rather racy symbol for love sentiment to be proudly displayed. Not to say that it wasn’t, but the shift back to wholesome Christian values made the outward display of love and affection more ambiguous and less overtly passionate in intent.

The Neoclassical Revival periods, the Rococo Revival and also Baroque combined with the Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite movements from the mid to late 19th century had a tremendous impact upon the artistic and design landscape in memorial and sentimental jewels. Changing social values meant that in the latter 19th century, the rose would be seen more as an individual love token, often in silver, or embossed into a locket (also commonly silver).

Increased mobility lead to the need for parting tokens, greater fallout from wars (Civil war, Indian conflicts) and higher population vs. industrialisation led to higher mortality, which impacted the nature of the self and how passions could be distributed in public. The latter topic also being the catalyst for greater access to metals and precious stones, leading to the creation of love tokens and also the rise in more organic jewellery designs, such as the Art Nouveau movement. A movement which adopted a passion for the natural world in organic designs and the use of materials within to enhance the organic nature of these jewels through colours and techniques. The rose, once again, took centre stage and dominated fashions and designs, as what better way to justify the love of the natural than with the symbol for love itself?

Augusta Bruce may remain in this beautiful ‘Nipt in the bud’, but her memory is not lost. Her life may have been cut short in the 18th century, but the clear love and dedication to her that was seen in her being a rose whose life was cut short is present.

While we may offer a flower for love, a rose may encapsulate the love and loss that is in the simple moment of giving and receiving. To consider one loved, as a beautiful rose, is a perfect sentiment of love and to cut it short is to mourn its loss.