Mourning Jewels: How They Were Worn, Part 2

The wearing of 18th century mourning jewellery set the template for numerous revivals through to the 20th century. The 19th century was the catalyst to popularise the mourning industry so much so that it created its own industry and became a part of popular fashion.

Much of our modern understanding of Western religious and social ceremony comes from these periods, expanding through industrialisation and colonisation around the world by the European empires. Wearing of jewels is important because of these factors would define them in another, either through acceptance or resistance.

Symbolic tokens of affection, memory and piety could be seen as a nationalistic tribute for a cultural event, or simply the message of a loved one who was holding on to the memory of another. The development of photographic technology during these times helped to capture the image of a loved one and disseminate it through all levels of society inexpensively and efficiently. With the rise of new technologies and better education, miniature portraits, silhouettes and the photograph would evolve to become smaller, simple to produce and able to be fitted perfectly inside a jewel.

By the late 18th century, the evolution of the ribbon slide into the bracelet clasp remained as popular through the 19th century as any other form of jewel. The following painting of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, wife of George II, (1789), shows its subject at the height of fashion, with shorter sleeves and engageante. On her wrists, she wears two pearl bracelets, both given by George. One clasp holds the portrait miniature of George and the other is his royal monogram. The painting was presented in 1790 to the Royal Academy, but displeased the king and queen, so it remained in Sir Thomas Lawrence’s possession.

Pearls and hair were the two most popular items for stringing a bracelet clasp. Discovery and trade led to the desirability of pearls, particularly from medieval and Elizabethan times onward. ‘Oriental’ pearls, originating from the oyster family, were the most desirable due to their lustre, which pearls from freshwater mussels and conch shells did not have. The Oriental pearls were bought to Europe from the Persian Gulf by caravan traders. The 18th century utilised materials for jewellery in opulent ways to denote the status of a wearer and match the changing social boundaries of new wealth.

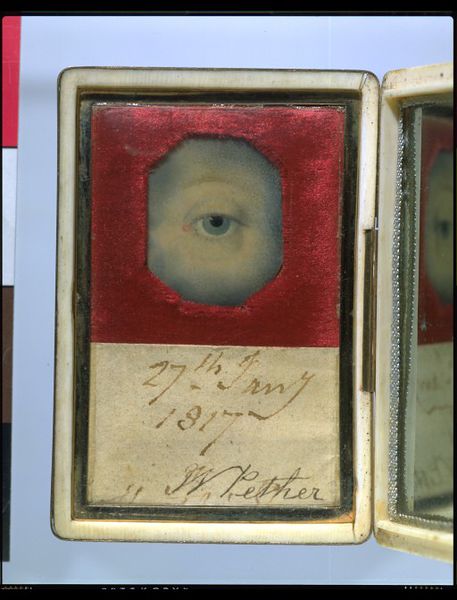

Miniature eye portraits are famous for their short existence and romantic context.

Eye portraits are considered to have their genesis in the late 18th Century, when the Prince of Wales (later, George IV) wanted to exchange a token of love with Maria Fitzherbert, the Catholic widow of Edward Weld. The court denounced the romance as unacceptable. However, a court miniaturist developed the idea of painting only the eye and the surrounding facial region as a way of preserving anonymity. The pair were married on December 15, 1785. Unfortunately, for the couple their union was considered invalid by the Royal Marriages Act because it had not been approved by George III, due to Fitzherbert’s Catholic leanings. More on this can be read in the article Mourning Fashion & Jewels During George IV.

Maria’s eye portrait was worn by George under his lapel in a locket as a memento of her love. This was the catalyst that began the popularity of lover’s eyes. From its inception, the very nature of wearing the eye is a personal one and a statement of love by the wearer. Not having marks of identification, the wearer and the piece are intrinsically linked, rather than a jewellery item which can exist without the necessity of the wearer.

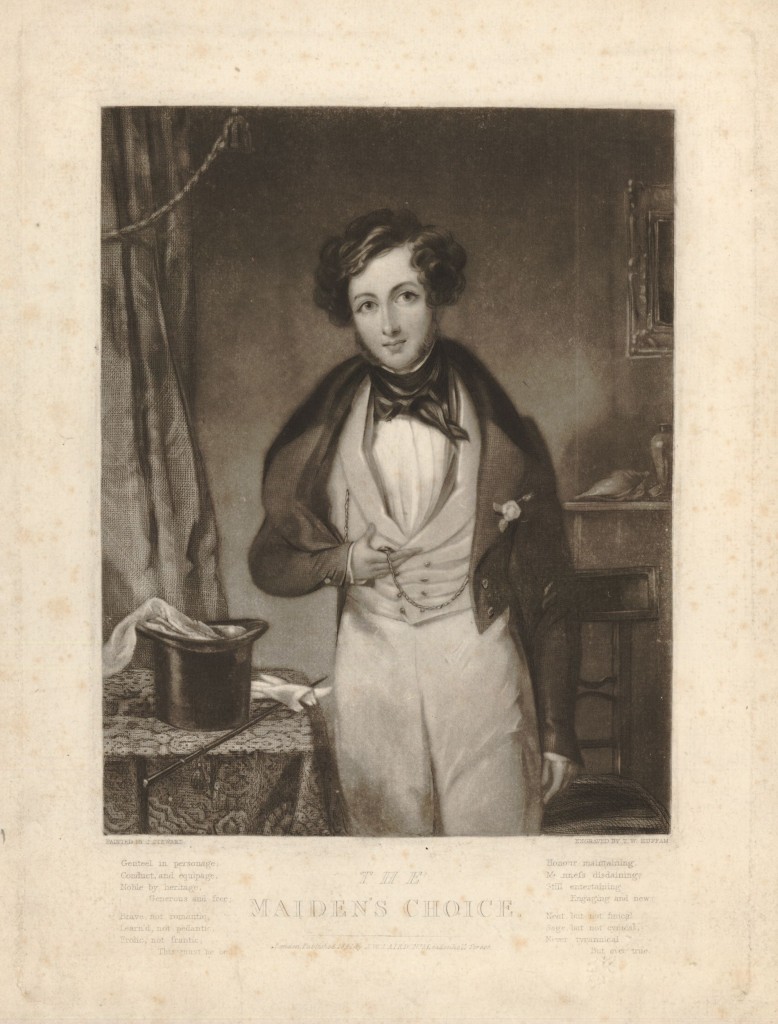

Seen in the miniature of the gentleman wearing the eye miniature, its anonymous nature is coyly placed to show its reveal from under the lapel. Romanticism in jewellery doesn’t judge the wearer for being in love with another, it is just a fashion that had become popular.

Anonymity and Romanticism are linked in the private nature of love between two people. Mourning and sentimental jewellery was popular because of their abilities to capture both of these elements. Having a locket produced with an interior miniature could be as important as the anonymity of an eye miniature. It is the speed of production that made the eye miniature and the silhouette popular ways to capturing the image of a loved one quickly. Interestingly, a bracelet with woven hair as the chain of the bracelet shows that the jewel references a loved one, but the image is clasped shut and private for the wearer only. There is no hiding the sentimentality of the jewel, but the tease to the viewer of the status of the wearer. Romanticism leads to lesser implication of negative judgement in jewellery, unlike the royalist miniature portraits seen in lockets, pendants and rings of the 17th century. Sentimental jewellery was popular enough to maintain its own status in popular fashion, not simply be a function of a relationship or mandated period of mourning.

It is interesting to see the evolution of this dress from the previous one of 1809. There are many more opulent mourning elements, with careful attention to how she is wearing her necklace. The lady is wearing a dinner party dress with a lace collar and benching around the hem. She has a white shawl across her arm and a wearing a white turban, an evolution of the white mourning cap. Figures were starting to become larger in the skirt and the under bust cut had moved back down to the waist for the hourglass figure. The crucifix is connected to a chain around her waist, white the floral necklace carries a locket. Drop earrings match the set, showing just how the accessory was becoming part of a lady’s complete fashionable look. They are also becoming large, something that would peak c.1860 in jewels, as dresses grew larger and wider. Mourning as an industry was integrating more into daily fashionable identity.

Fashion and mourning in linked in this British fashion plate from 1809. The Neoclassical style had permeated through society, having its foundations from 1760. Here, the mother and child are at the height of classically influenced fashion, known as the “Empire” style. With their high waistlines, fitted under the bust, gathered skirt, gloves and curled hair, this would be suitable for evening wear. Mourning practicality does not suit this dress in all the ways that the many accessories of the time could be adjusted for daily wear, such as mourning pins, bracelets, rings and brooches. Even in the context of the urn design, this is highly stylised, being the aspiration of the fashion plate for a modern woman in mourning. Around her neck, the subtle black and white necklace design is the only addition of jewellery. Being idyllic in its depiction, this is a balance for the black and white of the outfit, rather than a literal image of a woman in mourning.

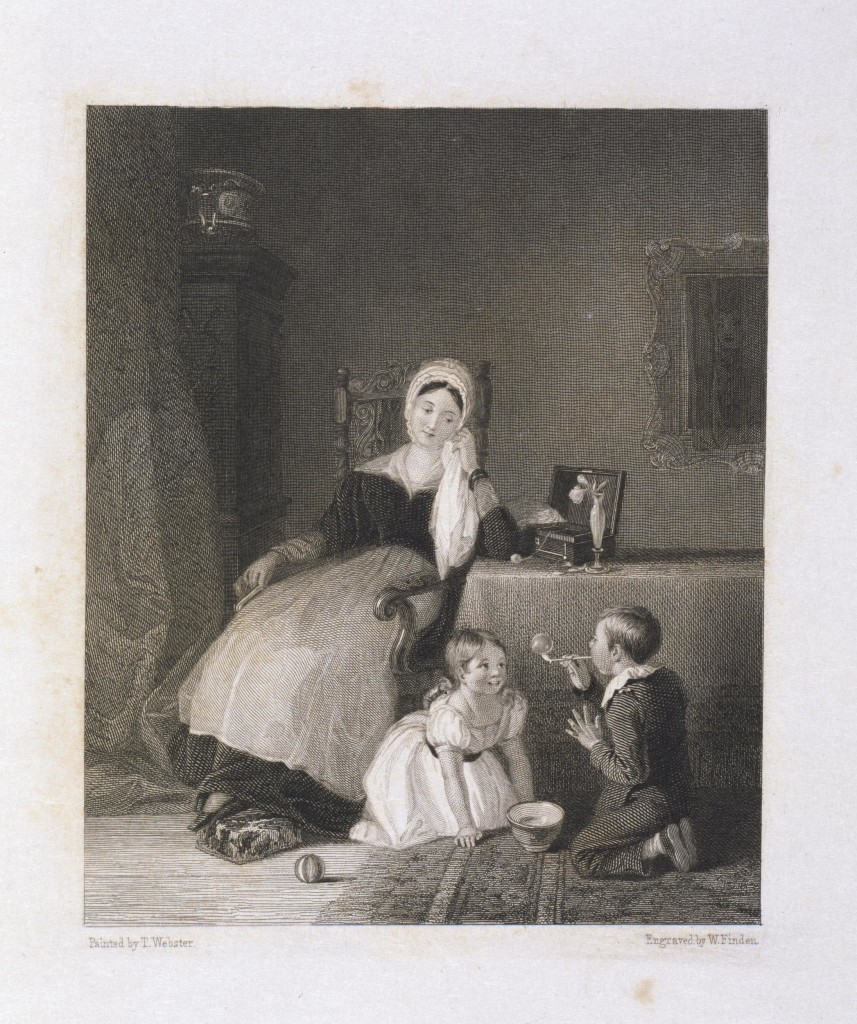

The lady sitting at the table in this print by T. Webster wears a mourning cap and a large bracelet at her wrist. Bracelets are important in the presentation of mourning, due to the space on the wrist that they can accommodate. In the early 19th century, the miniature portrait was one of the more popular tokens of love and affection that a person could give. Men fighting in the Napoleonic wars could have a pre-designed portrait (with uniform) quickly customised to their identity and given to a loved one. Clasps became bigger and more oval shaped, strung with pearls or hair. Worn for dinner parties, their lack of daily use and keepsake status has led many of them to exist to this day.

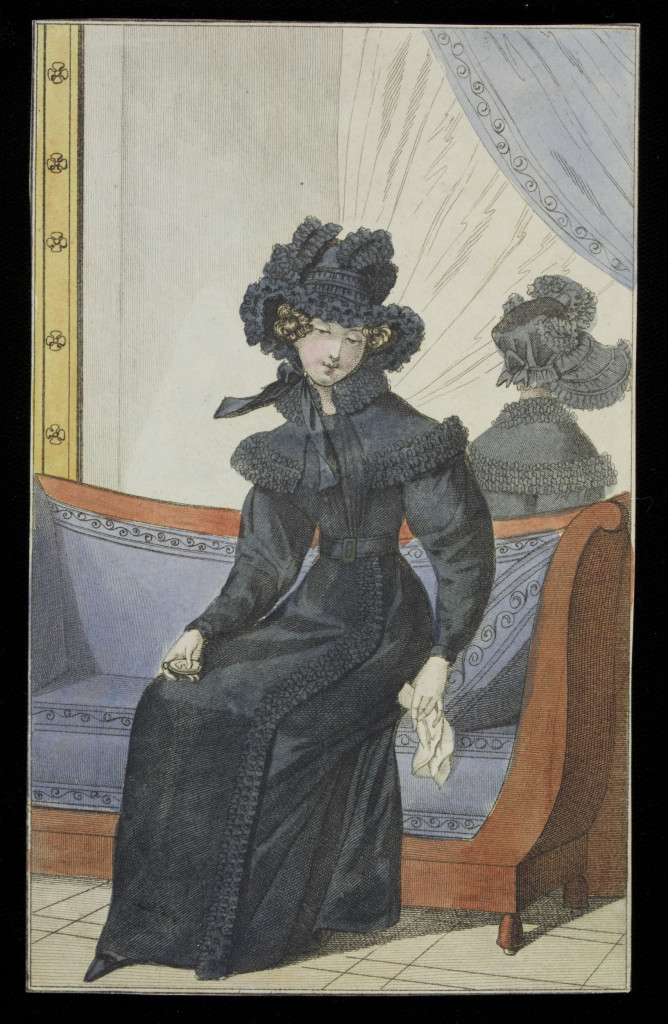

In this fashion plate from the 1830s, the lady can be seen in full mourning dress in black silk and crape. In her left hand is a handkerchief and in the right she holds a miniature portrait, presumably of the departed. Miniature portraits, being large to wear, were commonly placed inside a compact that would be ideal for travelling and safekeeping. The loved one could look down upon the visage of their departed, alive or dead, and retain that token of memory. Interestingly, the size of the miniature, painted on ivory, vellum or card, grew to a large proportion just before the advent of photography in the 1840s. More and more people demanded keepsakes of their loved ones and the industry, artists and talent grew to accommodate.

Sentimental accessories show just how important the Romantic movement was within the fashion of 19th century society. Many peripheral accessories for costume and daily use were produced, from Albert chains (chains buttoned into the waistcoat through a T-bar with watches and other accessories attached), to chatelaines and stick pins; the daily tools of usage were attached to the body for access and use. Utilising these accessories as functional objects which were also fashionable, hair and gems were infused within these items to produce a memento of a loved one and a keepsake for memory. Previous to the 19th century when the amount of accessories that adorned the body wasn’t so robust, items such as watches were decorative items for an affluent society. Many were engraved or moulded into sentimental shapes, such as the memento mori watch below:

The watch was a great catalyst for the advent of the popular wearing of the chain. From the time of Henry VIII, wearing a watch as a pendant near the waist became a fashion. On January 1-2, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the noted diary writer wrote on January 1-2 1668 “..and took coach and home about 9 or to at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing…”, indicating the importance of status to wearing such a timepiece on the body. Affluence in the timepiece demands an equally adorned chain to hang it by. By the 18th century, the waistcoat/bolero was the popular form of wearing the watch, diagonally across the body.

While the chatelaine was also worn with equality between men and women; its development and craft lent by the influx of Huguenots emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

The name of the Albert chain comes from Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert (1819-1661), who wore his chain horizontally, attaching it from right pocket to left. Albert’s influence on Victorian society, culture and art cannot be overlooked, as it was through innovation led by Albert, that industry developed and produced many of the items that would be used in day to day life and also attached to the chains. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened.

Cut steel was a fashionable material for jewellery, buttons, buckles, sword hilts and watch chains in the decades around 1800. They were made from brightly polished rivets, their ends faceted to imitate diamonds. Such pieces gave a grey but powerful glitter. Originally an English speciality, the production of cut steel had spread to other centres in Europe by the early 19th century.

The crowned monogram decorating the hook-plate has not been identified. Courtesy V&A Museum.

It was Albert’s death in 1861 that led to the perpetual mourning of Victoria and the absolute apex of the mourning industry. Her influence in popularising sentimental accessories through gifts given to her and by her impacted the popular culture of the 19th century, leading to the popularisation of flora and fauna symbols in daily life. As this had been prolific during the 1840s and 1850s, Albert’s death changed popular fashion, as the Court requirements of mourning dress and the monarch’s perpetual mourning, led all elements of mourning tokens to be created and worn. The popularity of jet and its imitations grew, as anything that could be produced at low cost rapidly found its way into the daily fashion of the public. Charms, such as the ones on the chatelaine above, could be added to the chains worn in daily life, from the popular ‘in memory of’ locket, to moulded symbols denoting a life cut short.

Photography and its development through the latter 19th century are ideal primary sources for capturing mourning jewels and their wearing in detail. Albert’s death had led to mourning’s permeation through fashion quite a direct one. The impact of Court rules and the close proximity of the European monarchy through family allows for an insight into the daily lives and wearing of jewels, as mourning and weddings were captured in imagery. Here, the group wears mourning dress for King Frederick William IV of Prussia. The group is comprised of Frederick, Grand Duke of Baden; Louise, Grand Duchess of Baden; Friedrich, the Crown Prince of Prussia and Victoria, Crown Princess of Prussia. The ladies wear heavy shawls and widow’s caps, but of note is the brooch at Victoria’s neck. Wearing the brooch at the neck with a high collar is one of the hallmarks of Victorian fashion. Brooches maintained size of around three inches, typically containing a lock of the loved one’s hair in a compartment in the centre.

Black enamel is the most popular mourning element for any jewel. Its colour represents death, as the absence of light and the passage into darkness is literally displayed in the design of the jewel. From its importance, the black enamel brooch worn at the neck is the perfect symbol to represent mourning in society. It is sombre, respects the loved one and displays the sincerity of love and sadness that a person has for another.

In this miniature, the brooch is seen in detail, with black enamel and pearls. As with the photographic references, this wearing of the jewel is typical and consistent through the second half of the 19th century. Fashion only adapted to allow for more brooches to be worn at the neck, rather than dropping the necklines. A sense of modesty had overcome society in daily fashion, one that was not provoked by the monarch and one that would cause the next generation of women to be looking for an end to the domination of mourning fashion.

Cataloguing royalty is the easiest way to discover mourning jewels in-situ, but the day to day life of mourning jewellery wearing was different. Physically, daily life is more demanding for a woman not of the aristocratic status, as is the access to wealth. While it is easy to think of the perpetually mourning woman, the wife and the mother still maintained the house and was required to perform daily labour. In this photograph, the McDonald family is seen, with a mourning brooch clearly displayed on Annie McDonald (1848-66?) against a backdrop, flanked by brick walls. It is a curious photograph, and acquisition of Queen Victoria, that displays life and jewellery in a closer context than those of the carefully staged.

Princess Alice became engaged to Prince Louis of Hesse on 30 November 1860; their marriage took place in July 1862, having been postponed because of the death of the Prince Consort in December 1861. The Princess is wearing mourning in this photograph for her grandmother, the Duchess of Kent, who had died four months previously. Provenance. Acquired by Queen Victoria. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust UK.

Princess Alice is wearing mourning in this photograph for her grandmother, the Duchess of Kent and is the perfect representation of the mourning ideal. Carefully staged, the photograph shows her looking away from the mirror and surrounded by crape and bombazine. She wears one large bracelet to her wrist and a brooch at her neck. During the 1860s, the voluminous nature of the sleeves and the skirt gave a narrower impression of the exposed neck and fall of the dress from the shoulders. Brooches were large to accommodate, but as seen here, were also quite small. It is the bracelet that looks to house a memento of a loved one, with the large clasp.

Victoria was the epitome of the grieving widow and viewing her in mourning was the ideal for how presentation of mourning jewels and clothes should be. This image of her with Empress Frederick in 1888 shows her wearing rings on three fingers of her right hand and two on her left. The multiple bracelets show an accumulation of charms in all materials, each sentimental and can be seen in the Royal Trust Collection. On her neck, she wears ornate jet beads, which were declining in popularity through the 1880s. At this point, Victoria had become a monument to sentimentality and mourning in her fashion. She had loosened up her presentation of mourning since her Golden Jubilee in 1887 on request of the Princess of Wales, though this did not change her sentimental perception of fashion.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, previously Princess Elisabeth of Hesse, married Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich in June 1884. In this photograph she is probably in mourning for her cousin Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, who died at Sandringham in January 1892. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust UK.

This 1892 photograph of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna in full mourning shows the change that the silhouette had come to in the late 19th century. Beginning with the earlier examples from the late 18th century, figures had slimmed, widened and slimmed once again. The widow’s cap remains in place, along with the brooch at her neck. In this image, Elizabeth clutches her right hand, displaying a ring on her third finger, which may have important sentimental connotations, however, there is no record of this. The Cross Formée at her neck is subtle and not at all like the earlier mourning brooches that would have dominated a costume like this. Pious to the point of selling her possessions, jewels and wedding ring after the death of husband Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, the image captures her at a point of being in mourning and regal. It also shows just how mourning was becoming compartmentalised into daily life, with the blur between fashion and mourning seemingly intertwined. Much of this led to the end of the mourning industry, however, what the mourning industry had given popular fashion was taken and adapted into other jewels of sentimentality that were worn in the same manner.

Worn

It is too simple to ask how a jewel was worn. Since humans have created jewels, the way we wear them is the most direct – how easily can they be seen? A brooch at the neck, a ring at the finger, a bracelet at the wrist. The reasons why they were worn there changed more for social reasons, such as the wedding ring, but there’s lesser so for mourning. Grief was commercialised and adapted into popular fashion as the modern period grew. If grief can be commercialised, then all the elements of mourning fit perfectly into the daily practice of living; the compartment containing hair is an obvious keepsake of a loved one, if surrounded by black enamel, then there is an obvious death for someone who views it being worn. It is through the 20th century that much of these practices have become lost to time, but in the nature of human behaviour, they will emerge if a keepsake needs to be worn; the brooch or pin can be shown, the ring worn, the bracelet presented. We need to express who we are and how we feel and as long as we have emotions, this will never change.