Mourning & Sentimental Jewels of the Georgian Era, An Introduction

“It is said to be peculiar to us, that our villages ape, so minutely, the fashions of our cities; that no sooner is a new fashion of dress, or of the sleeve alone of a dress, introduced into the city, than straightaway, as by magic, every sleeve in the country, from the shoulder of the squire’s wife to that of her youngest maid, is fashioned precisely after the same model, or, if varied at all, exaggerated for the purpose of being extremely fashionable.” – p. 22 , Sedgwick, Charles (Mrs), “The Would-be-genteel Lady” The Jewel: Or, Token of Friendship, R. P. Bixby and Company, 1839

The Georgian period is a title which encompasses a long stretch of time, from 1714 to c.1830. Using its literal title, this is correct, in that George IV reigned until 1830, though William IV is often considered for this period to 1837. What is difficult when it comes to fashion and identity, is that not one catalyst can immediately change an entire nation. Influencers can have their changes react through a society that can afford to pay an artisan to craft a jewel or change a dress in the style of a popular fashion, but even this takes time. Jewels created in the 1680s were still evolving through 1700 and 1720, before and after George I had taken the crown.

Victoria took the crown in 1837 and her reign lasted until 1901, which encapsulates a great deal of the 19th century, but doesn’t standardise it in a way that many modern viewers consider the 19th century to be black dresses, jet and perpetual mourning. Apart from the massive change in mourning and sentimental jewellery from the c.1760 period, there’s substantial bleed through of style from year to year in fashion. A style that had little precedent in the 1770s evolved through into the 1840s, with technology being one of the few major catalysts to create a fundamental change in sentimental behaviour. Photography and its evolution being a style that evolved through the 19th century and its adaption into jewels eclipsed silhouettes and miniatures, which became a more boutique item for the wealthy to commission the artist.

What did evolve during the 18th and early 19th centuries was the development of new wealth, industry and mobility. The previous generations had dealt with the schism of religion and the focus on a new humanist perspective, now the exploitation of this in fashion was the fundamental conceit to what we know of as fashion today. Promoting identity in new wealth could move a lady into a higher status of marriage, or create a lifestyle for a young gentleman to travel Europe and move from city to city.

Through this mobility and wealth came the rise of the artist and new sentimentality. The Georgian period grew many styles which are still in fashion today. The fancies of the late 18th century carried into the mid 19th century, yet all had the one ideal of capturing a loved one in the moment.

Eye portraits, the heart symbol, Neoclassical urns and the allegorical statements of love are all built into the identity and psyche of Georgian culture. As with all human development, much came from new discoveries and access to materials. During the Terror, aristocratic French jewels flooded the market, driving down prices and allowing jewellers to create new objects of art. Gold given in the Napoleonic wars to defend a country promoted jewellers to use lesser gold and make finer, larger jewels. Berlin iron came from this, a form of patriotic jewel (gold given and returned with an iron jewel), which carried into the First World War.

With the following pieces, you will see the different fancies of the Georgian period and discover much more of the culture and fashion surrounding mourning and sentimentality.

Link > A French Mourning Pendant in 1787 For A Child

The elements of fashion and mourning come together in a pendant made for a child in 1787. The Georgian period is identified most for its use of symbolism in allegorical settings. To this day, most are retained and understood for their meaning, but their immediate recognition is more difficult to interpret as we move further away from classical texts being our bedrock of education. However, the fundamental rules apply, with a female and/or male in mourning, followed by an urn, a willow and other symbols carry on from these primary ones. Once this is understood, identifying Georgian jewels is much more simple.

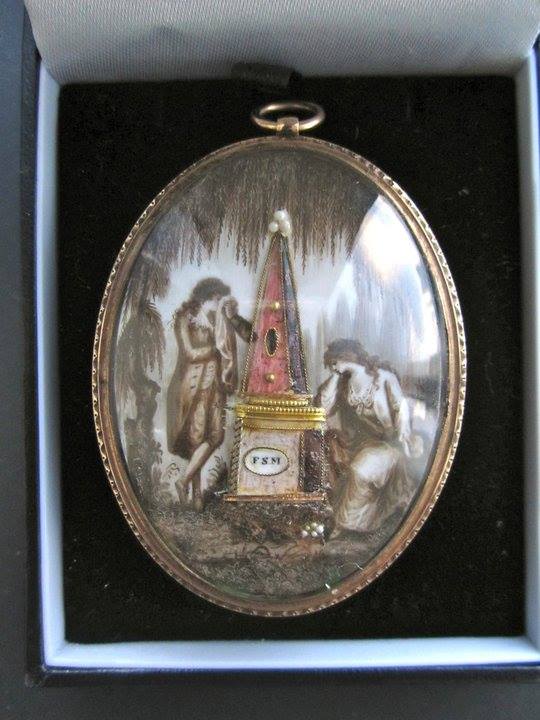

Link > “Rest In Peace” – An 18th Century Mourning Pendant

In this example, the elements of pure Georgian mourning come together. The urn and willow are perfectly detailed. This article shows just how diverse the range of materials were for the late 18th and early 19th century, with the use of pearls showing access to the Orient during the time. In the symbolism of the willow, you will read about how it was a popular motif for its time, being a status symbol for fashion in mourning in the context of Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787.

Link > 1774 White Enamel Mourning Ring

While not a Georgian concept in origin, white enamel was expounded upon through its use in jewels for the unmarried and the young. This worked well in the context of mourning in white and has its roots in classical art. Read about rings, bands and popular fashion, as dictated by Marie Antoinette.

Link > A Coffin & A Male In A Stickpin. 18th Century

Having the female in the mourning can be allegorical or personal, with the person being a direct representation of the wearer. When the male is painted, however, it is almost always a personal representation, as it was quite rare. See how the gentleman in mourning resonated through stickpins and rings with the sepia painting of the 1780s and 1790s.

Link > Sarah Honlett, Age 14 ‘Toward the Heavens’ Neoclassical Brooch

Allegorical depictions are of the most ideal kind. Here, faith, hope and charity balance with the female mourner, who is pointing towards the heavens, balanced by the willow. All of these elements of hope and sadness resonate today, with a small jewel telling a grand tale.

Link > 18th Century Costume, Mourning and Art in a Neoclassical Miniature

In this miniature, there is a perfect capturing of the lady in mourning. From her dress, to her sitting, she was painted in a moment in time by the artist and it shows with this miniature. Miniature portraits grew to fit in the palm of a hand by the turn of the 19th century, making them standardised by the Napoleonic wars, enough so that soldiers could be painted in a Neoclassical ideal in costume, then the artist could tailor the hair and colour of eyes for the subject.

Link > REGARD and the Georgian Heart

The ‘Georgian Heart’ is a symbol that still lives today, being the most identifiable symbol of love created. The heart, given to another is a true offering of love and it developed through the 18th century to be what we know of today. This locket is a magnificent example of the high form of style that it captured. Through this article, there are links to several other pieces which trace its roots back to the source.

Link > The Georgian Eye

Notorious for its connection to George IV, when a young Prince of Wales wished to marry the Catholic widow Maria Fitzherbert, the ‘Georgian Eye’ is a fancy that lasted from c.1790-1830. Holding an anonymous image of a loved one’s eye, which could be quickly produced, is a beautiful concept for young love. These were also used for mourning purposes, as one can tell from their setting within a teardrop, black enamel or a down-turned eye.

Link > Gems and Smaller Jewels

By the early 19th century, jewels became larger, yet finer in detail. The ‘magical properties’ of gems meant that they were used in a higher volume and symbolic sentiment were woven around their use, replacing a lot of the allegorical classical scenarios that had come before.

Link > The Grand Tour

Greater mobility led to jewels moving in and out of Britain at a rapid pace. Skills from Italy, France and abroad were chosen by young men who had the wealth to be trained on a ‘Grand Tour’ as a rite of passage. Using the memento mori symbols, a gentleman could announce their maturity and understanding of living through the desecration of the body and knowing their mortality.

Link > Love in Allegory

Another 18th century fancy is capturing of social moments within jewellery. Love combined with a popular moment, media event or political event could be produced by a jeweller and remain relevant in its moment. With this ring, there is a great connection to a moment in the mid 18th century, which has not be reproduced. Look to this rings style under the bezel for the rosette shape and how to identify many contemporary rings.

Link > The Eternity Twist

Twisting hair is an ancient invention, but what is seen from the 18th century is a perfection of its style. A simple weave leads into the ‘knot’ as a symbol and just what that means for allegorical statements in jewellery.

Link > Halley’s Comet and the Moving Into The Victorian Period

Halley’s comet passed by in 1835 and this captured the imaginations of the public and the jeweller. Many brooches of the Halley’s comet style are still in production today, with the long tail being stylised. This brooch has a lot of detail connected to this moment, but the article has more on its origins and the beginning of the Victorian style.

Survival Through Sentimentality

The Georgian era saw humanity, romanticism and fashion combine in a way that provided the basis for our standard ways of offering love to another in popular culture. Without much of its exploration of classical culture and its political unrest, there would not have been the value of identity that modernity understands it to be.

If any of these examples prove a point, it is that humanity wants to retain a memory of what makes a person love and feel. Each of these jewels takes a moment in its context and captures it in time; from travelling performers, a twist of hair or the very look in an eye, the Georgian period was one of instant sentimentality and love.