Mourning Fashion & Jewels During Victoria

Victoria’s reign from the 20th of June, 1837 to the 22nd of January, 1901 was the height and decline of the mourning industry. Her success at building stability in the empire was due in no small part to the traditional values she installed through her family appearance. Being the queen of an empire where the sun did not set emphasised the importance of visual identity around the world. To be considered an individual in the United Kingdom was to uphold its crown values around the colonies. The 19th century saw the greatest expansion of the United Kingdom to ever occur in history. Previous monarchs saw aggressive colonialism and transcontinental war leaving behind a legacy of protectionism for identity within a country and a clear understanding of mortality. Communities had more chance to achieve wealth for their families than ever before, with the Industrial Revolution providing a new mass consumerism that demanded products to stay in fashion. Supply and demand, driven by governments that required spending, only monopolised on mourning. From this, mourning warehouses became entire end-to-end suppliers of mourning fashion and accessories, providing for every element of the household to be in mourning.

But why is this so identified with the Victorian era? Queen Victoria’s entering into perpetual mourning after the death of Albert was the major catalyst for the public to adopt this as fashion. Whereas, previous Court mandates had led to the mourning stages being enforced (with the upper class finding lower classes adopting their mourning style distasteful in the 18th century), Victoria turned many of the peripheral items of mourning into regular fashion.

With a high mortality rate and the identity of the mother as being the symbol of the family, the requirement of the woman in mourning would lock some into perpetual mourning themselves. Be it the loss of a child to a relative, mourning was a requirement. Such stringent rules would lead to the decline of the mourning industry, a decline that even the massive losses of WWI and the flu epidemic in the 20th century would not bring back.

Victoria was born on the 24th of May, 1819 to Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (the fourth son of George III) and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Victoria was raised under the Kensington System, which was built to ensure Victoria’s subservience to her mother and her alleged lover, Sir John Conroy. She was raised with strict rules that required her to be close to her mother, tutor or governess and her interactions were tightly controlled.

Victoria’s interest in sentimental jewels, as well as those that were created or worn by her, became popular in the public. From the serpent with an emerald head engagement ring she was given by Albert, to the locket she was given as a little girl, her sentimentality resonated through the United Kingdom, and became identified as the elements of proper sentimentality and mourning around the world.

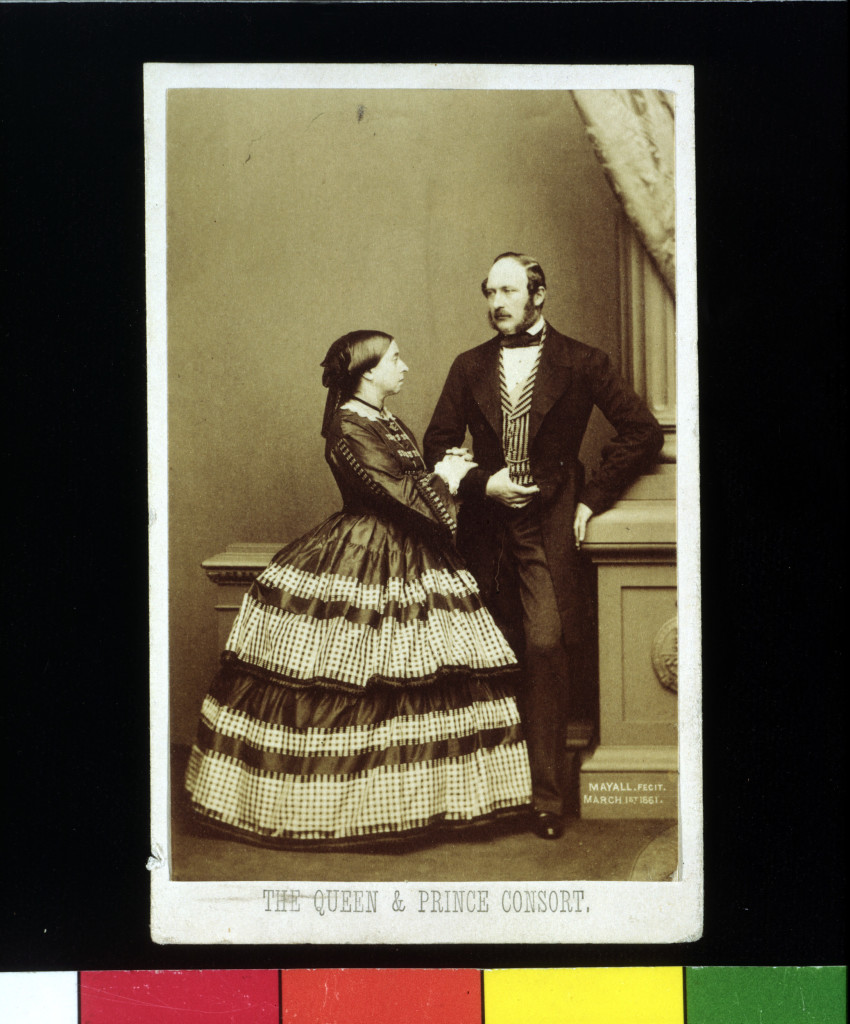

She ascended the throne on the 20th of June, 1837, being the 5th in a line of succession that had led to her through mortality and lack of offspring. Whig Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, became close with Victoria, acting as a political advisor. Her inauguration was held on the 28th of June, 1838, after which she took residency in Buckingham Palace. The relationship between Victoria and her mother was not cordial, and as an unmarried woman, her mother was required to live with her. Much to the shock of Victoria, Lord Melbourne’s suggestion was that she marry to break this convention. However, in 1839, Victoria took an interest in Albert, who was on his second visit to England, an interest that was reciprocated. On the 15th of October, 1839, Albert proposed to Victoria and they were married on the 10th of February, 1840. Albert became Victoria’s political adviser following their marriage, replacing Lord Melbourne. The union of Victoria and Albert not only became the focal point for what the Victorian ‘family’ should be, but also had political importance to create fashion that could reach all levels of British society. As an advisor, Albert’s initiatives led to great advancements in the 19th century, and his union with Victoria would become a catalyst that would peak the mourning industry.

Love doesn’t require historical importance, nor is it an emotion that occurs in an isolated moment. Rather, it shared between us and defines the entirety of our lives. Love between Victoria and Albert had the benefit of royal status, which elevated all the trappings of their love into the households of regular families. From the introduction of new technologies, as this ring shows with the use of the photograph, to the customs and colours of dress, their love was the definition of what style was in the 19th century.

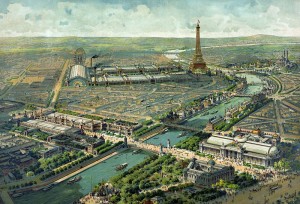

Innovation led by Albert, Prince Consort cannot be understated for its values and impact upon society. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened. Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society – a progressive step, and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

The 1850s led much of this standardisation, with the family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art. Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing.

Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century.

Understanding that popular fashion in modern culture is created through a method of control from a dominating body for the sake of conformity in society through identification, it is easy to understand why the charm bracelet as a concept became popular in the 19th century. Queen Victoria was the one to popularise mourning, through her love of fashion and the adaption of the industry towards her perpetual mourning following the death of Albert, Prince Consort, on the 14th of December, 1861.

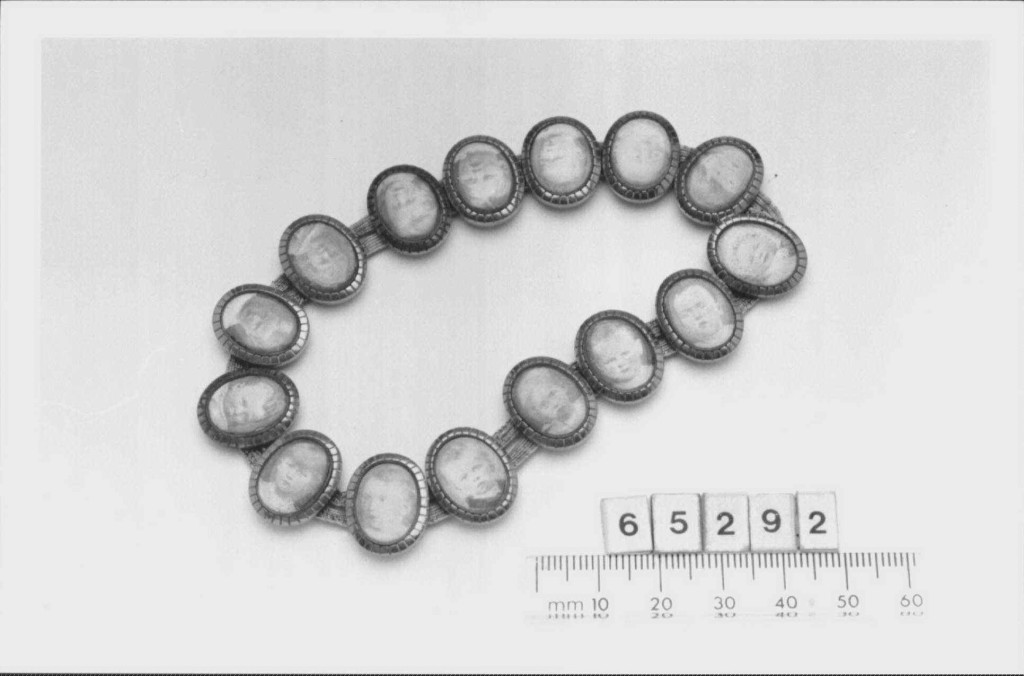

Victoria wore this bracelet until her death in 1901, where it was part of a group of jewels placed in the ‘Albert Room’ at Windsor Castle. Prince Albert had died in this room and the Queen left instructions for a specific list of personal jewellery to be placed there and not passed on in the family. Each locket contains a personal memento of hair or a photograph for family, which can be seen through the dates and inscriptions upon the lockets themselves. There is a consistent theme with these jewels, as Victoria maintained the heart symbol as her preference, but this wasn’t standard for the common charm bracelet.

For her grandchildren, Victoria wore this bracelet of fifteen oval painted photographs, set in gold, with the names of the children on the reverse. Being later in the 19th century when photography had overtaken other methods of memorials due to their low cost and ability to capture the sitter nearly instantly, this bracelet shows Victoria’s adaptation for change in sentimentality. It is fashionable, but still retains the quality of a love token that she had in her youth.

While remaining singular in her concept of sentimentality and how that should be represented, Victoria did change and adapt through fashion. The imposition of this within society after her imposed mourning period was more difficult to a wide population in order to adapt towards that fashion and became emblematic of the Victorian period itself.

Bolder style was in its element during the 1860s. This can be attributed to the mourning of Queen Victoria from 1861, but also tells of the evolution in costume and everyday dress. The larger styles of the mid-Victorian era had taken hold, with female fashion becoming larger and the jewels needed to adapt.

In a perfect example of how the larger style of the 1860s was presented in style, note this large locket for Albert and the below image of Victoria from c.1862. Her crinoline is wide and heavy, dominated by a heavy black cloak. This locket matches the style of fashion in mourning – simple, large and without any of the excess Rococo design which had been popularised by the Gothic Revival period. The Empire styling of jewels in high fashion was also popular in French mourning jewels, which tended to be of the same style; large, onyx and in simple shapes.

Fashion is required to work with jewellery and not against it. Jewellery is the dominant feature that can dress a gown up or down, with the more elaborate jewel to make a larger statement in society. In mourning, the desire to have a keepsake of a loved one provides the mourning industry with enough scalability that cheaper jewels were just as accepted as this locket in the context of fashion.

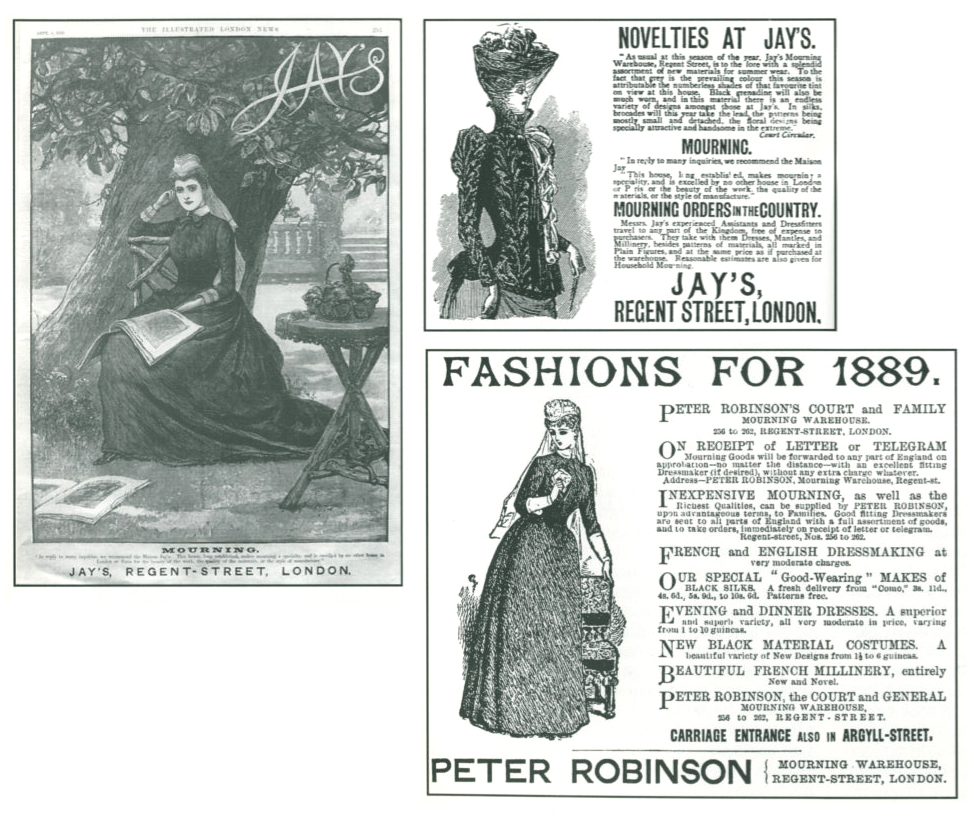

By the latter century, costume and function were tightly connected for women. Dresses of separate bodice and skirt were worn in bombazine covered in crape. Underwear was often white chemises, drawers and under petticoats slotted with black ribbon. Black caps, crape trimmed bonnets, and long veils.

First mourning lasted one year and a day, outdoor garments for this would be shown by the plainness and amount of crape, jet jewellery was permitted. After one year and a day, Second stage was introduced. This involved less crape and its application to bonnets and dresses became more elaborate. It was frowned upon if this period was entered into too quickly and it lasted nine months in all. The Third stage (or Ordinary stage), introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted.

Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months. The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life. Hats, shawls, mantles, gloves, shoes, fans all changed during mid century, and pagoda sleeves from 1850-70 were fashionable, designed to be stitched to the outer sleeve to cover modesty from the lower arm and wrist. Wide skirts from the 1850s-70s, tie back fashions of the late 1870s and the ‘S-bend’ look of the early 1900s all were adapted to mourning fashion, without a clear definition of difference between them. Throughout the post 1880s decline, in the 1890s, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure.

Jet was presented to the public at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its popularity grew exponentially, facing almost immediate Royal patronage from France, Bavaria and of course, England. Thomas Andrews was the ‘jet ornament manufacturer to HM the Queen’ from 1850, and this would be a most prodigious position to hold, as upon Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria only allowed jet jewellery to be worn at court. Society followed on from court etiquette and mourning fashion and culture swiftly became part of mainstream culture.

By the 1870s, the annual turnover of the Whitby jet industry was said to be over one hundred thousand pounds, with a jet craftsperson earning between three and four pounds a week. From 1832, there were only two shops employing twenty-five people to 1872, where two hundred shops employing fifteen hundred women, men and children, taking over the landscape of Whitby. Development of machinery, such as the lathe, also helped to facilitate the growth of jet production meeting the high public demand for jet pieces. However, demand was so high that soft jet was imported from Spain and France, mainly for beading (as previously mentioned, soft jet tended to crack and many surviving pieces reflect this today), giving the jet trade what was considered to be a ‘bad name’, hence the attempt in 1890 to trademark ‘Whitby’ as a quality of jet. Jet was also seeing great competition in lesser-quality imitations which were far cheaper and by 1936, only five craftsmen were left. By 1958, the last Victorian trained jet carver had passed on.

Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crape gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act.

Their decline came in 1886, with the 1880-82 period of fabric being ordered at 46,000 packets of fabric to 30,000 in 1892-94. This is a steep decline that relates to the end of the mourning industry and its fashion. The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways.

On the continent, however, much of the exports of Courtaulds’ sales were to France, as in 1899, more packets of crape, known as ‘Crepe Anglais’, were sold than had been previously seen. Courtaulds offered a softer crape, which was popular, rather than the stiffer fabrics, and was advertised as such. By 1921, ‘Latin Countries’ were the major exporter of crape, which speaks to the change in dominating mourning styles from the ecclesiastical to the fashionable. Being in popular fashion, mourning was challenged; not something that was mandated as it had been, particularly through the period of the First World War and its high mortality. The pomp surrounding mourning reduced to be personal. Mourning and its stages weren’t enforced and not an indictment on the family, so what a person felt was more allowable to be presented within society for mourning ritual. As to the crape and its exports, this was more popular in Catholic cultures, which still retain formality around public mourning.

Black crape remained at a cost of around £200,000 between 1913-1918 and saw a slight increase in 1919, but dissolved very quickly after this. Fashion magazines were the new focus of what was acceptable in mourning, not the Court, signalling the end of aristocratically led fashion. A widow was suggested to spend one year and six months mourning a husband. Gazette du bon ton outlined the new suggested mourning fashions in 1920. ‘Grand Deuil’ was the deepest mourning period, utilising wool and crape, ‘Petit Deuil’ was the second stage with black silk and taffeta with dull stones, while ordinary mourning was white crape with pearls and diamonds.

Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, those from the older generation still maintained many of the mourning rituals which they had grown up with. Even after the death of King George V in 1936, the Vogue suggested that people outside of Court “…in the interests of thousands who depend on catering, entertainment be leading a normal social life.” This is a major repealment of the Court mandates of the 19th century that standardised mourning to the highest degree.

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

This is why the Paris Exhibition was so fundamental in disseminating new styles throughout mainstream culture. Wealth from America and driven by industry was empowering artists to go beyond the Court/aristocratic styles that hadn’t had the early 19th century monetary drive and lockets such as this ampersand piece could thrive. Look to the design of this piece; the Nouveau elements, from the organic curve to the floral outcrops.

With the high level of accessible and affordable travel in the early 20th century, there was a rise in sentimental tokens being produced in high quantities to be given to loved ones while travelling, or bringing home as a remembrance of the voyage. Combined with the new Romantic movement that looked towards the 18th and early 19th centuries, many jewels were reproduced to represent those that had come before.

Various levels of quality reflect these jewels, with new methods of production and transit leading to higher mobility between cultures for their global population. Establishing these production methods created standardised love token representations that are still relevant today. The Neoclassical representations of love and affection, in this case cupid with the bow and the cherubs, with the temples and different displays of the female, underpin modern jewellery based around sentimentality. Indeed, even cameos can be identified to their era by the contemporary hair and fashion styles. Here, we have a lady displaying her ankles and raising her skirt, with low-cut bustling and tied hair. The poorly defined floral elements flank her, but attention has been given to her costume’s lace.

Marcasite was a popular element of jewellery in the early 20th century, moving its interpretation from being a diamond substitute to becoming a popular element in its own right. You can see this used as the border of the piece. Surrounding this are faux pearls, with the damage to the north of the piece.

Identification can be an issue for many of the jewels produced during the early 20th century. With the Romantic period using many of the early 19th century elements of love and affection, so many pieces that would not seem in fashion were created during a time when emerging art forms, such as the Arts and Crafts / Art Nouveau development, dominate the perception of the time. Love and sentimentality didn’t change overnight since Queen Victoria’s death, but evolved with fashions that certainly did look more organically to the world around. This piece shows an adaption of the old and the new, but still tells a tale of love.

In an industry that grew through the love of Albert and Victoria, the objects and fashion mobilised society to drive a demand for mourning objects and fund the lives of artists and industry to provide for this. Through two people, the catalyst of love in death and the respect that this demands in a social context provided the basis for modern concepts of mourning, fashion and symbolism.