Jewellery Transition From Death to Life

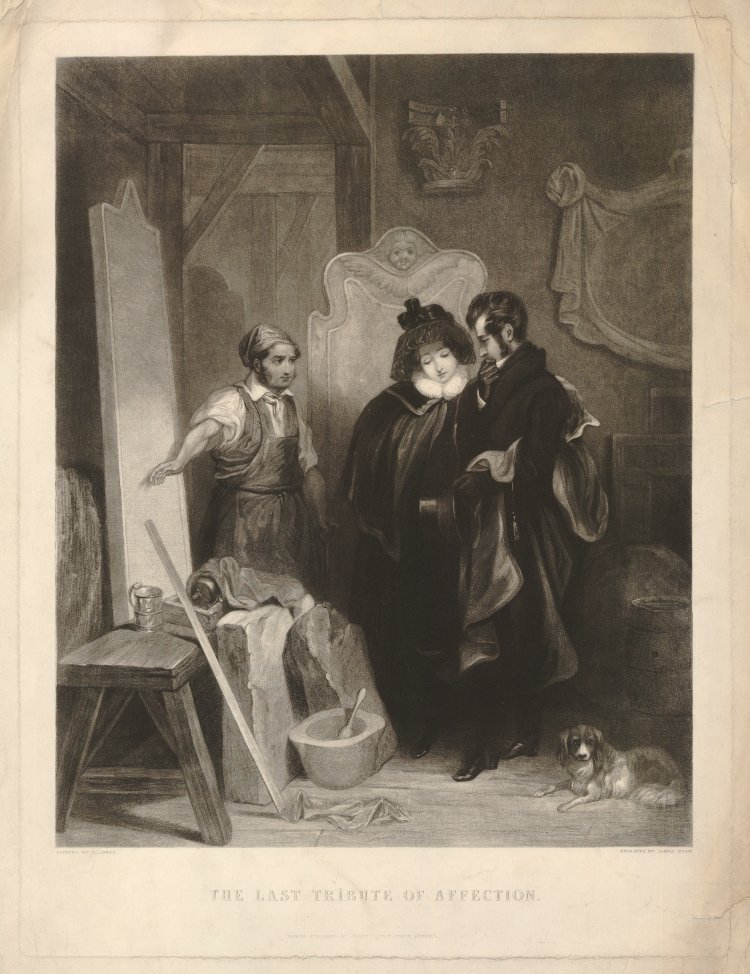

Stages of mourning are the steps towards reappearance in society. Each stage has its rituals to enable respect and memory for the departed one. These reflect the values of a family and those of an individual within a respective society. If that person was in mourning in England and moved to a foreign country, then those values still remain. Their construction is to firmly hold on to a socially constructed ritual that moves beyond ecclesiastical. A government can create these through general periods of mourning and popular movements can follow the Court mourning rituals to copy their style. Naturally, the business that was created from these movements was enough to finance the very structures of modern insurance companies, an evolution from the ‘burial societies’, which guaranteed a wealthy burial and not that of a pauper. The affectation bestowed upon this expensive funeral led to the creation of ‘mourning warehouses’ and retailers that created bespoke memorial items for a loved on, depending on their period of mourning. The entire house could be outfitted with all the trappings of mourning and so could the individual.

It is necessary to establish that the periods of mourning changed over time. There’s not one static answer to the question of when an enforced period was mandated, but as mourning became more engrained across the standardised Victorian society, this is generally where most point to as being the periods when mourning was institutionalised. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, the period changed due to general rule, often that of a monarch or a popular figure, such as Princess Charlotte in 1817, to give a strict period of specified grieving. These stages morphed as time went on, building on what had come before. As an early reference, Louis Mercer details 18th century mourning practice in ‘Le deuil: son observation dans tous les temps et dans tous les pays, comparée à son observation de nos jours’ (1877), in which he also covers mourning in antiquity and other religions. It is in the 18th century that the following insights are found in this rough translation:

“…the Court of France in the eighteenth century, as the result of an order published in 1765 under the title: Ordre chronologique des Deuils de la Court, all usual ceremonial observed in these circumstances is thoroughly described in this book: One was the great mourning for father mother, grandfather and grandmother, husband and wife, brother and sister. They called great mourning those shared in three stages: wool, silk and Small mourning. Other shared grief do only two stages, black and white. We never draped in recent bereavement, and, whenever things not draped, women could wear diamonds, and the sword men and ball money.

The mourning of father and mother was six months. During the first three months we wore wool poplin or flush Saint-Maur,… with tapered hanging cap,… sleeved white crepe… If it was in a dress, it wearing hats… sleeves and… crepe… After six weeks we left the cap… The last six weeks were small mourning. It was black or white with brocaded gauze and similar amenities. We could then wear diamonds.

Etiquette of mourning for grandfathers and grandmothers was the same, but the grief was only four months… For siblings, wool for three weeks: fifteen days silk, eight days of Small mourning. For aunts and uncles, mourning was three weeks and could wear silk…

Mourning for cousins lasted fifteen days… For uncles fashionable Britain, eleven days: six black, five white.

To cousins from a sibling, a week, five days in black, three in white.

Grieving husbands was a year and six weeks.

During the first six months, widows wore wool Saint-Maur, tail dress turned up by a strap attached to the petticoat side, and which is brought out by the pocket; the folds of the dress were arrested in front and behind; both front joined by staples or ribbons; pagoda sleeves; the coiffiire batiste with large cuffs; a flat sleeves rank and large hem… handkerchief… a black crepe belt, stapled in front to stop the size of folds, the two loose ends to the bottom of the dress; a scarf pleated crepe from behind; the large cap black crepe; gloves, shoes… the sleeve coated flush Saint-Maur, without trim… The six other months were black silk sleeves and trim pancake white and black stones, if you wanted. During the last six weeks, black and plain white… the choice of the widow… diamonds could be worn”

The first (deepest) stage of mourning is what one would expect. Black, non-reflective surfaces around the house and the body, allowing for the crepe industry to grow from this. What makes the second stage of mourning so interesting is that it’s where jewellery becomes a primary focus. While the first stage was helped to popularise Jet and its imitation jewels of the 19th century, previous jewels weren’t as widely accepted. The second stage was when the introduction of gems could be used and with the importance of gems from the 17th to the early 19th century in jewels of hierarchy and wealth, mourning a loved one without the gem to support the jewel of a loved one took away from its social value. By the late 19th century, fashion writer, Mrs John Sherwood, wrote in Manners and Social Usages (1887) that ‘diamond ornaments set in black enamel are allowed in deepest mourning and also pearls set in black’. Diamonds have been used for the second stage and beyond in jewellery much more typically, so the concession for diamonds in first stage jewels by the 1880s was welcomed, but did not prevent the decline of the mourning stages.

Looking at gems and their usage in jewellery is one of the better ways to identify the use of a jewel in a stage of mourning. Rings left as bequeathments often followed the standard convention of mourning styles, with black enamel and hair placement. These jewels were given to close family and friends upon request, a popular request in a will from the 17th century. Wearing these jewels around the time of the funeral was more typical than after the event, as they work within mourning regalia, then kept afterwards as a keepsake. Women who entered the stages of mourning and its fashion were held to the stage convention far more strictly than men. This is where the requirement of the very stark deep mourning stage didn’t allow for the trappings of fashionable pomp.

Gem usage in jewels is prehistoric, as the colour, scarcity and romantic quality of the gem translates to status. The very jewel itself holds a more intrinsic quality of beauty for having the gem in place. Mourning, for all the industry that built up around it, is a sombre affair, so creating too much affectation to distract from the death devalues it. It’s through the symbolism related to the gem that makes it a worthy companion to the mourning jewel. The ‘magical properties’ of the gem can symbolise an increased love for the deceased, rebirth, piety and friendship. Through the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the language of gems changed, which was a combination of greater access to the gem through trade and travel, putting more prominence on their usage. As seen with the use of diamonds in the late 19th century, the allowance for gems in the second and third stages of mourning helped turn mourning into a fashionable period.

Mercer’s breakdown of the mourning stages and their custom follows this table:

With that in mind, the half mourning stage is the one where diamonds are permissible. This dates to 1765, a time where the Neoclassical period was about to greatly change the perception of human identity through a connection to the classical world. Its impact on mourning led to a change in convention, putting much more emphasis on Romanticism and sentimentality.

This ring dates from around the same time as the Ordre chronologique des Deuils de la Court and shows the emerald pastes surrounding an oval bezel with plaited hair. Seed pearls alternate the pastes, making the ring highly decorative and perfectly sentimental. During this period, hair doesn’t accompany sentimental symbolism, but it becomes the primary sentimental focus. Hair is being assisted by the pastes and the pearls, both popular elements for their time. Paste, in particular, was necessary to emulate precious gemstones. By the early 18th century, the Rococo period was in full effect and the use of gems was becoming more and more popular to fit into the style. Access to new wealth and changing social structures in Europe put more emphasis on wearing jewellery in high society, leading Georges Frédéric Strass to develop paste. Paste jewels are leaded glass that is cut and polished with metal powder, emulating the facets of a cut gem. In essence, much of the crystals popularised in the 17th century were designed to copy the cut of a diamond in the same manner. Paste, known as white “diamante” or “strass”, were backed with coloured foil and could replicate a ruby, emerald or sapphire.

Seed pearls were particularly popular during the second half of the 18th century and used liberally throughout jewellery. From decorations, such as in this ring in the border of the bezel, to full three-dimensional scenarios set in the jewel.

Because of this increased use of gems and new materials, mourning jewellery adapted to the style. Being of the latter stages of mourning, or for the half mourning period, jewels with the symbols of death appeared to be more opulent in their designs. This is where mourning jewellery grew its identity, blending into the daily fashion of the time. Previously, the Baroque and Rococo periods shared much of the jewellery designs with the mourning jewels in their general designs.

In this amethyst from 1765, the general Rococo style, with the rolled interior band, fleur-de-lis shoulders and twisting ribbon motif was the popular style for a fashionable ring between c.1720-1760, but with the addition of the name in the band and the black enamel, it takes on the mourning attributes. Set in the bezel, the amethyst introduces the purple colour into the mourning jewel. For jewels of this style, the consideration of the amethyst being a latter addition, or one of several rings made for friends, without hair, fit within the nature of the mourning ring being for distanced friends or a further stage of mourning.

For these jewels where colour and symbol began to blend over stages of mourning and into fashion, statements of mortality were just as personal as statements of living. This is a follow on from the memento mori ideal of knowing when you will die and living a life to equal that thought, but also heavily skewed into respecting the life of friends and family around you, in a time of humanist feeling. In this ring, the tree of life is depicted, showing the allegorical fashion of the time, but also the personal nature of what the wearer’s beliefs were. The tree is made from embroidered hair The style has changed slightly from the woven hair ring, being more squat in shape and the cut of the amethysts more refined. Purple is once again on display and the ring would be a quite fitting jewel for fashionable society.

In 1789, the French Revolution affected jewellery wearing and production to a great extent. The First French Empire under Napoleon retained and grew the popular Neoclassical styled jewels, maintaining their position as the primary leaders of fashion. Even with the hostilities between 1793-1815, the English closely followed Parisian styles.

By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles may be enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security if fleeing the country.

Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

In 1797, the Paris Company of Goldsmiths was reinstated, after being abolished in 1791, reintroducing many of the goldsmiths from the reign of Louis XVI. By 1798, hallmarking was established in France, making it compulsory to stamp jewels under three standards of purity; 750, 840 and 920 parts per 1000. They were also stamped with a maker’s mark (the maker’s or sponsor’s initial) and symbol in a lozenge-shaped stamp.

Filigree jewellery and fine detail to gold work had its inception here, as there was as shortage of money and goldsmiths became inspired by French peasant jewellery to produce finely detailed gold with lesser materials. Seed pearls, basic gems (such as agates) were also popular, as can be seen in the following pieces:

In the above, we can see how the fashion of fine gold and the access to seed pearls from the Orient and turquoise made for highly detailed and inexpensive jewellery. Large enough to be seen and influenced by the Neoclassical style, this was a society adapting to the hardships that they were surrounded by. The changing nature of jewellery symbolism is very important in these jewels to note, as it would affect the 19th century. Fine gold work, the use of literal symbols in the bird, crescent moon and serpents, created with, or flanking, the gems themselves. Sentimentality was changing from a painted scenario to these direct messages. With the higher volume of gems in use, a greater focus was placed upon their ‘magical qualities’ and symbolic value. Wearing a sapphire might bring the wearer increased good or bad luck, for example. For more on the values of gems, a list can be found in this article:

> The Symbolism of Gemstones

Turquoise is another common material that blurs the line in the latter stages of mourning jewels. Without a clear marking of mourning, they must be relegated to sentimentality. Queen Victoria had much to do with popularising jewellery, from sentimental to mourning, during the 19th century. Turquoise in particular was popular, as Victoria gave her twelve bridesmaids turquoise brooches in the shape of a Coburg eagle, which symbolised Albert’s family. Their blue colour is familiar to that of a forget-me-not and this is a motif used in both mourning and sentimental jewels.

By the 19th century, the evolution of colour and symbolism had developed well into mourning jewels. Symbols could adapt meaning when used in conjunction with other symbols. The Victorian hand brooch is a typical icon of the 19th century, but when used with a small wreath of yew for mourning, or a fan to show adoration, or even sports, with a tennis racket and ball.

This is where the latter stage mourning jewels become more difficult to identify. The ancillary symbols used could change the meaning of a jewel and the conversation around its use requires further investigation.

These brooches date from the 1840s and, much like the earlier bird brooches, literally depict their subject. Interpretation is more difficult, if one is to see beyond their aesthetic value, into what their purpose is.

“Text from the Catalogue of the Hull Grundy Gift (Gere et al 1984) no. 664:

Black mulberry means ‘I will not survive you’. The use of amethyst may have a significance beyond the purely natural; because the purple colour of the stone was closer to black than most other gemstones, the wearing of amethyst was permitted in the later stages of mourning (see Morley 1971, p. 67). The use of amethyst may thus confirm the mulberry’s message of mourning. See 666. (Charlotte Gere).”

The more that nature becomes part of symbolism, the greater the use of natural designs in formal jewellery can be acceptable in social levels that were under tighter regulation for formal presentation.

When combined the with the rise of floral styles within jewellery design, turquoise was a decorative material for its colour and how it could embellish gold design. The adaptation of the floral style was one that resonated with the language of flora and fauna. The Illustrated Language of Flowers by Anna Christian Burke categorised over seven hundred elements of flora and fauna, which gave the Victorians a resonance of design elements to represent their emotions in jewellery and ephemera designs for gifts towards others. Even more symbols were built upon this, increased only by the discovery of challenging thought in a time where science and religion were becoming equals, to make the smallest element of design important to represent a relationship in society.

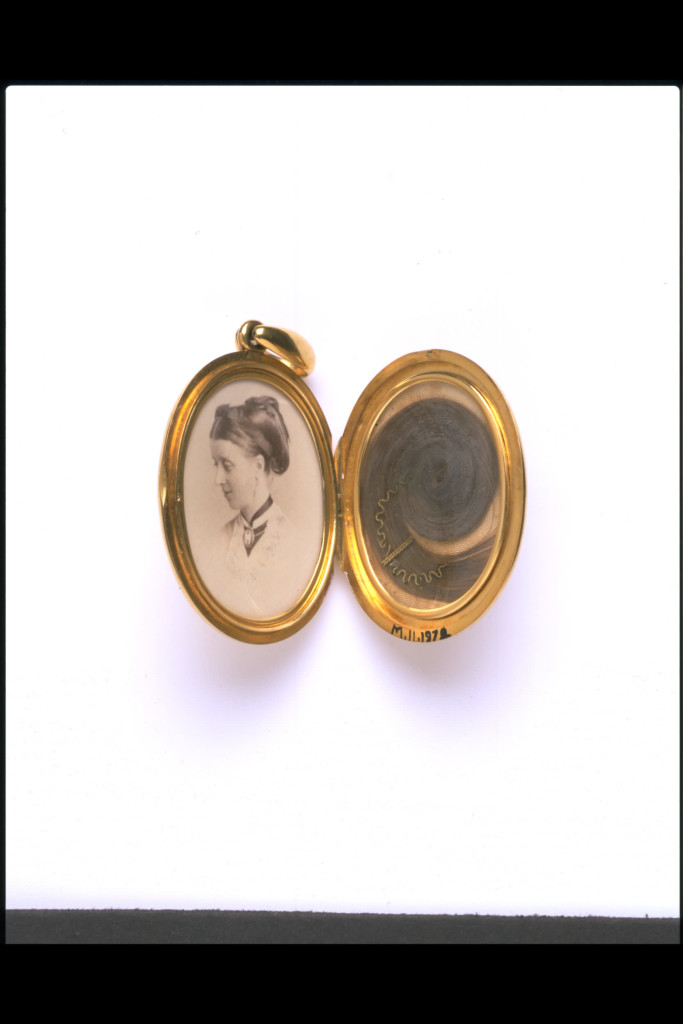

For all the additions in colours, flora and fauna symbolism, mourning jewellery simplified in order to remain consistent from the latter stages of mourning through to wear in daily life. Lockets have been one of the most important forms of jewellery in mourning and sentimental jewels. Their ability to be worn above or below the clothes and always over the heart makes the intention purely personal and focused on the element of love.

In this locket from 1871, emblazoned with the diamond monogram of “L.B.F.”, outlined in black enamel, the mourning style of the post 1870 period can be seen. It has been suggested that the widowed husband purchased the locket and gave it as a keepsake to one of his wife’s close friends or relations. With the inscription of ‘In remembrance of L.B.F. Oct 7th 1871, from C.G.S.F.’, the suggestion is a valid one, as the giving of a jewel or a bequeathment had been solidly built into social behaviour.

What makes this locket so important is just how refined it is in its style. If not for the monogram on top, it could easily be repurposed by future generations as a mourning or sentimental locket. It lacks the excess in design that makes it heavily mourning, outside of the black enamel, so it perfectly conforms to the design aesthetic of the time. Large, bold and simple was the popular style of the late 19th century, as the Rococo revival of the 1860s was beginning to lose popular flavour in mainstream fashion.

It is emblematic of the decline of mourning as a fashion. It’s not so much that the stages of mourning had been rejected as a sign of piety, but that it had been so closely integrated within Western society that it was a natural aspect of daily life. In much the same way that mourning values are part of death today, it’s accepted that one will be in a period of grief without it being indoctrinated through a isolated culture. For this reason, lockets are still a popular jewel for mourning today, being either new or re-appropriated, one can wear the lock of hair or a photograph of a loved one and it’s not seen as being locked into a stage of mourning.

In this article, we’ve seen the development of colour and materials within latter stage mourning jewels, the change in perception of symbolism and its integration into sentimental and mourning jewels. These elements show how mourning became so integrated into modern life. Without this trajectory of jewellery and its perception, identity couldn’t follow the humanist path of individual recognition and affection. Publicly showing one’s love for another is a bold statement today, so considering that these jewels developed during a time of higher social pressure, it’s remarkable that gems, colours and designs could be worn so prominently.