In Memoriam / In Memory Of Rings, 19th Century

Black enamel bands are the most recognised of mourning jewels, being placed in very visible positions for others to see, easy and cheap to manufacture and all for the purpose of creating the wearer to be a walking tombstone for the person who is deceased. Their ability to be re-appropriated or kept by a family lineage is important, as these rings are far more important as tokens of remembrance and genealogy, as opposed to their commercial value.

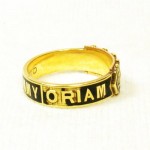

By looking at two different eras of mourning rings, we will see their importance as cultural markers. The following ring is from 1827:

1827: Mourning Ring, 18ct Gold and Enamel, Hallmarked London 18ct Gold Dated 1827 inscribed with “Wm (William) Wrightson ob 26 Dec. 1827 At 75”

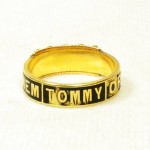

And this ring is from 1881:

What can be gathered from the two different eras, times when the meaning of mourning and the imposition by Court values created the necessity of mourning?

Firstly, the design of the ring speaks in volumes to the society within which is was created. The first example from 1827 has the excessive flourishes around the edge of the band which were incredibly popular in jewellery design of the 1820-40 period. This was ushered in through the Gothic Revival period and its use of the Rococo styling that was can be seen in architecture (such as cornices) and furniture design. Its use, combining floral and acanthus motifs, are decorative and dominating, imposing a style which was opulent upon a society that was moving away from the excess of the Regency Era and towards the simpler pre-Enlightenment Christian values. Dominance in style is a reflection of the majesty of God and final judgement, where a life lived in piety would be rewarded with entrance into heaven. This is a motif worn on the finger to show the values of this for the deceased, who is in this case William Wrightson.

Compared to the 1827 ring, the 1881 piece is reflective of Victorian standards, where design was simplified and direct; the sentiment is drawn to the top of the ring, where the gypsy set pearls are inlaid to the stylised buckle. Post 1870s mourning jewels are far more streamlined to the Empire style, which was influenced greatly by classical elements of Roman, Greek and Etruscan in the late Victorian era, yet retained the simpler elements of each. Note the pieces below:

Previous Rococo embellishment is lost to the clean, straight lines. In this, the buckle and the enamel take pride of place. Enamel is one of the most important factors in mourning jewels, denoting at what stage the jewel would be worn in the three stages of mourning custom, clearly denoting that the jewel was created for the purpose of death and also the status of the person wearing it within society.

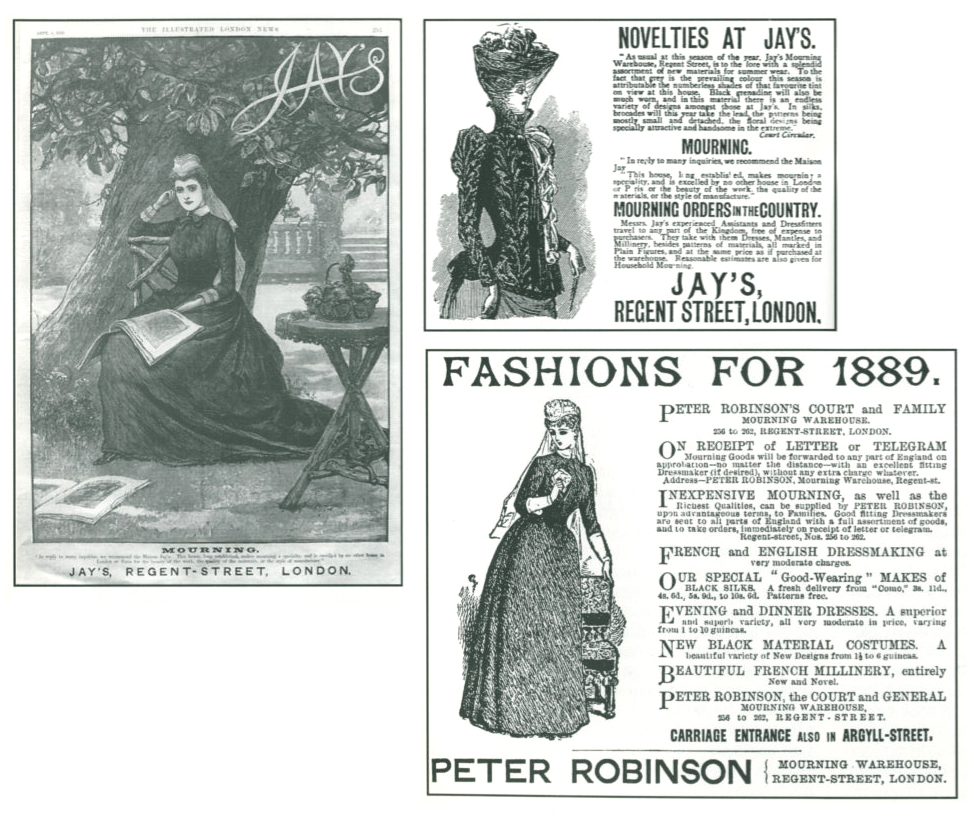

Black enamelled rings were easy to create with low gold content and make in great numbers. The producers in Chester, Birmingham, Exeter, Newcastle, Sheffield, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dublin and London could supply Britain and its colonies with a large supply of rings that were transported for the purposes of mourning. A jeweller colour simply tailor the ring for the individual, or a mourning warehouse (such Jay’s; see below), could supply all the products necessary for mourning to a family, including the rings.

However, we see in this ring for Tommy, that the ring was quite bespoke:

In 1881, we have the standardised mourning Victorian style, yet we have a personal statement etched into the ring. For construction, this was the concept the ring was built around. Unlike many other rings with the ‘mother’ and ‘father‘ titles pre-made into the band and created within a series of different sizes, this ring was made to order by the person in mourning for Tommy. ‘IN MEMORIAM TOMMY’ would be a set pattern that ‘Tommy’ was adapted to, rather than being a completely new design. Granted that ‘Tommy’ is a five letter name, the design could accommodate other names if the jeweller had to make another bespoke jewel for another, hence other rings may exist with similar designs.

Looking back to the earlier ring, we have a similar style for the sentiment, but one which is far more standardised. ‘IN MEMORY OF’ is the most consistent statement found in jewels. As a collector or historian, identifying these rings, or any Gothic Revival jewel, is quite easy. Lettering in the enamel inlay is the most telling factor, with the highly decorative Gothic lettering harkening back to Middle Ages illuminated manuscripts (hence its connection to the Gothic Era).

Comparing this to the 1881 ring, having the standard ‘In Memory Of’ statement doesn’t relegate the earlier piece to be any less bespoke, as the cultural need for mourning accessories had been producing pre-made mourning rings since the early 18th century, when higher production and reduced labour was introduced along with the Industrial Revolution. Zeitgeists, such as the death of Princess Charlotte, the high mortality rates from the Napoleonic Wars and the cultural unity that resonates from these, create a mourning industry that was emerging as its own commercial entity by the 1820s.

Bands with the black enamel and ‘In Memory Of’ statement were produced in high numbers, with various levels of quality and differ with weight and gold content. Simpler, cheaper ones were produced in two pieces, with the interior band being a separate piece from from the outer casing, which has the gold Rococo embellishments. Heavier pieces, which tend to be earlier (around 1810) are more narrow in the band and one solid piece. It wasn’t until the late 1820s and 1830s that the Gothic Revival was standard as a uniform and popular design that the rings could be produced in such numbers that they would have a steady demand.

As a late Victorian jewel, this ring shows the development of the style. Using pearls and the buckle motif show that the ring was at the height of mourning jewellery for its time; a time when many of the designs in the Arts and Crafts movement led to aesthetic jewellery being produced for decoration, rather than resonating back to mourning jewellery as it would have during the turn of the 19th century and the Neoclassical movement’s influence on jewels.

What can be seen in the Neoclassical example of 1792 is that popular style was part of sentimental jewellery and that acknowledged mortality and life. The 1881 ring was made during a period of Queen Victoria being in mourning for twenty years; a period of standardisation in the monarchy which had not been seen in the early modern era. During the time in which the Neoclassical piece was made, style was influenced by the monarchy and aristocracy, due to the investment of the monarchy into the arts, the new wealth from the Industrial Revolution creating greater mobility for society to invest money within fashion and greater transit and communications between cultures influencing new styles.

The Tommy ring knew its status within society, as morning was identified as a specific style in the public eye. A person wearing this ring would clearly be acknowledged within mourning and the trappings of this would be without any decoration that would make them any less than sombre.

Symbolism within the pearl and buckle/garter motif are two-fold. The pearl represents tears and the buckle/garter is there to denote piety, love, respect and the honour of remembrance for the loved one (a remnant from its chivalrous history), yet the styles are so stylised by the Victorian uniformity in utilising these elements for so long, that they are subtle decoration for a ring that would act more like a tombstone for the wearer to remember the loved one by.

Viewing the continuity of a mourning ring between different eras is often the best way to understand the impact a certain time has on jewellery in general. Knowing that a political, cultural or artistic event may have changed popular fashion in such a way as to relate to mourning and mortality is important to understand the broader context of jewellery design.

Here, we have two rings that were a generation apart, yet tell us a tale of their values and times. Both were made under similar circumstances and both show a firm connection to their cultural sensibilities. From the high production of their style to the black enamel and the inscriptions, these rings were made for necessity and love within culture. Earlier examples can help to show that even these rings are an evolution, but no element about them cannot be understated for their creation and gravity of their meaning.

- 1881: Buckle design

- 1881: Enamel and Pearls

- 1881: “Memoriam”

- 1827: “In Memory Of”

- 1881: Pearls and Garter

- In Memoriam TOMMY 15ct Gold, Split Pearl, Enamel. Date 1881.

- 1827: Border elements and font design

- 1827: The floral motif also works in the enamel inlay

- 1827: Gothic lettering

- 1827: Mourning Ring, 18ct Gold and Enamel, Hallmarked London 18ct Gold Dated 1827 inscribed with “Wm (William) Wrightson ob 26 Dec. 1827 At 75”

- 1881: “In Memoriam Tommy”

- 1827: Note the inscription inside

- Mourning band, c.1827 with the acanthus/floral design around the band.

- 1881: “In Mem-“

- 1881: “In Mem-“

- 1827: Wm (William) Wrightson ob 26 Dec. 1827 At 75

- 1827: Gothic lettering