Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire’s Mourning Ring

What we leave behind is often the memory of the influence we had upon people’s lives. Often, a time and a place are right for a person to make their impact upon every element of society, from culture to politics. In terms of what they physically leave behind and how they were commemorated after they had passed away, mourning jewels are prime artefacts to show how people wanted to share the message of memory. In this mourning ring for Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (7th of June, 1757 to March 30, 1806), the ring represents the modest design that represented a cultural icon for her time.

Making an Impact

Jewels that have a connection to someone of such importance generally conform to their modern fashion. This is important, as the jewel would be worn in contemporary fashion for the status of being seen, so it is required that the jewel is relevant in its contextual society. Indeed, Georgiana was an important person for her time. From her status as a popular social figure, she brought together all the elements of the Enlightenment and took a major step into the national spotlight. She was a lady whose prominence during the 1770s and 1780s encapsulated science, literature, politics and society, then gave an unnerving push against anything she did not believe in. She became a caricature in politics, yet was at the height of fashion. The modest ring at the heart of this article shows how personal it is, as it is as humble as she was grand.

Georgiana’s politics led her to become a focal point for the Whigs during the late 18th century, promoting her to be a popular figure of resistance towards the crown. A member of the Spencer family, Georgiana was inclined towards the Whigs due to her family leanings. Her marriage to William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, allowed her own voice to promote her political values, as William was largely removed from politics due to his position in society. Georgiana campaigned for the Whigs in support of her distant cousin, Charles James Fox, which were largely anti-crown in 1778. The Prince of Wales supported the Whigs in defiance of his father, a disruptive move that resonated with the fashionable elite. Georgiana held political gatherings in the form of dinners at her house, a move which resonated through society and put her in the public eye as a figure of resistance.

Hosting intellectual gatherings was not unique during the second half of the 18th century, a practice that had grown from the Enlightenment. Intellectuals, artists and fashionable members of society came together to challenge pre-established thought and generate new concepts of the self in areas ranging from politics to art. Of note, the Bluestocking movement of the 1750s met in houses of the fashionable Elizabeth Montagu, Frances Boscawen and Elizabeth Vessey. The Bluestockings were created to foster a community of intellectual discussion. Though the concept was developed by women, it was supported by wealthy men, which brings into light the nature of the times. That there was a society which could allow for this form of intellectual debate and development to discuss new ideas, art and literature is removed from the times previous to the Enlightenment.

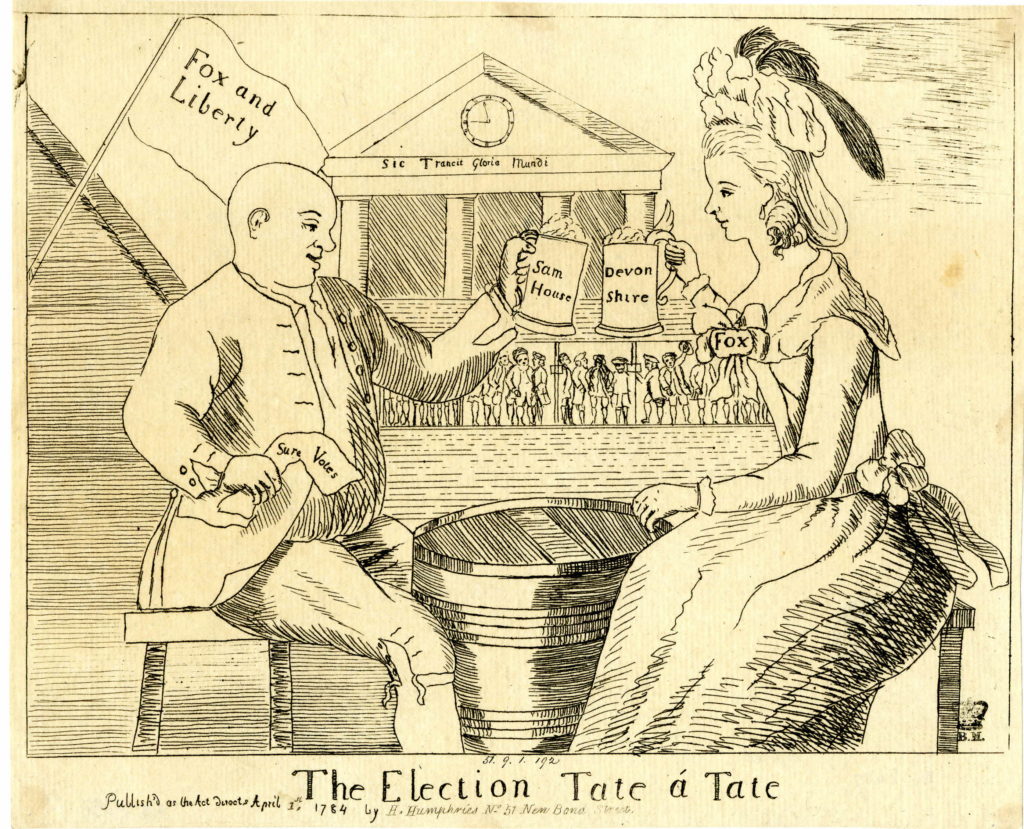

Georgiana’s impact in politics and society culminated during the 1784 general election, where she was satirised in a series of prints called ‘THE DEVONSHIRE or Most Approved Method of Securing Votes”. Rumours swelled about her trading sexual and monetary gifts for votes, to which her mother tried to persuade her to back down from her activism, but she continued on. After the success of Charles James Fox and Lord Hood, she reduced her involvement in politics, but remained behind the scenes until her death.

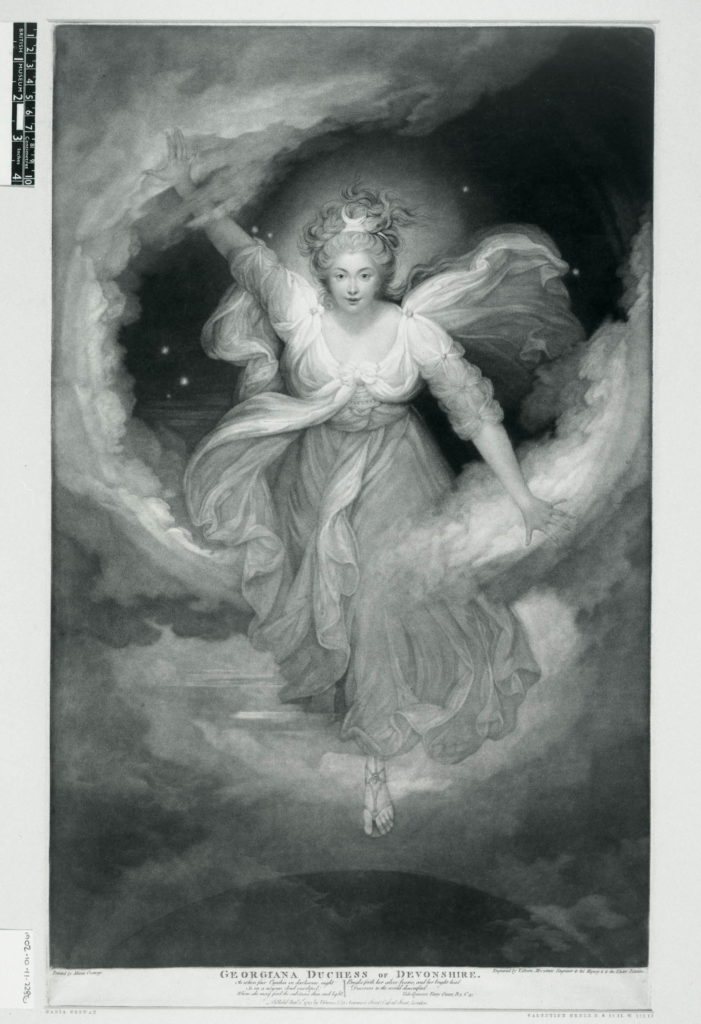

Always at the height of fashion, Georgiana embraced popular styles that helped promote classical fashion in society, from plumages to muslin dresses. Here, she is depicted in a print as Cynthia from Spenser’s ‘The Faerie Queen’, by Maria Conway in 1783. Cynthia notably was the moon goddess in the epic poem, where Christian and Arthurian legends intertwine.

Georgiana was interested in science and literature, to the extent of writing her own works and participating in science experiments, Along with Thomas Beddoes, she helped establish the medical research facility in Bristol, named the Pneumatic Institution in 1799. She also began collecting crystals for scientific purposes in Chatsworth. Her work in prose and poetry led to the publishing of Emma; Or, The Unfortunate Attachment: A Sentimental Novel in 1773 and The Sylph in 1778. The latter of these was a semi autobiographical expose of aristocratic behaviours and was published anonymously. Memorandums of the Face of the Country in Switzerland was first published in 1799, and finally, The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard, a poem for her children, was published in 1802.

Etching, 12 April 1784.

Favourable pastimes for the upper levels of society during the Georgian period involved gambling and Georgiana took to this with a great passion. She amassed a great debt during her life, ranging from four thousand pounds, which her husband gave her as an annual stipend, to three hundred thousand pounds, for which she asked her parents for a loan. Upon refusal of this debt, the duke reimbursed the creditors. During her life, she would try to keep her debt hidden from her husband, asking for money from the Prince of Wales and the banker, Thomas Coutts.

Her later years involved exile in France and a return, to which she nursed the duke from gout and took an interest in science and literature. Her interest in politics never waned, spending time trying to re-establish the Whig party and suffering a surgical scar on her face from treatment to an eye illness. This uninhabited her to her looks and she regained prominence in society. She passed away on the 30th of March, 1806, surrounded by family and was buried at the All Saints Parish Church in Derby. Reportedly, thousands of people mourned her at Piccadilly, where the Cavendish home was located.

Setting its Style

Standardisation of design in the 1810-20 period greatly reduced the size of mourning jewels. There are factors that caused this, as the Napoleonic Wars had depleted much of the European gold reserves, so goldsmiths had to be smart in their designs and maximise what gold they could. As can be seen in this brooch from 1806, the grand styles of bold and simple geometric lines changed the larger and more oval styles used at the height of Neoclassicism. It’s an unassuming style, but it is very defined by its time.

Of note, this ring for Queen Charlotte shows the evolution of the style in a more regal manner. Its use of the swivel and the black enamel are all consistent with Georgiana’s ring, but have the flourishes that are worthy of a queen. This ring was made 12 years after Georgiana’s, but it is striking to see how jewels that would come later actually conform to the earlier style.

It takes away from the elaborate opulence of painted allegorical messages – a woman weeping next to a tomb in Neoclassical garments, with an urn and a willow tree painted in sepia tones. The message at the beginning of the early 19th century became defined in the use of colour, enamel and gems. Gems took on their own meanings. Following the looting of aristocratic property during the French Reign of Terror (1793-4), gems flooded the European market and dropped the value, allowing fine jewellers to create new designs. Foil paste approximations, seen in ‘DEAREST’ and ‘REGARD’ rings, mimicked the colours of actual gems, as their popularity and use soared.

Currently in the Royal Collection, this ring has clearly been worn and shows its royal provenance. Having a mourning ring created for one’s passing was factored into wills, with several rings being common in the last will and testament of an individual. There’s no clear indicator as to who wore the ring, but often they were not worn, yet kept as a keepsake. The wear to the enamel at the reverse of the ring is typical of a ring worn on a daily basis, showing that she was clearly cared for and loved. The swivel to the bezel shows her woven hair in the reverse, but unlike many of the colour-matched hair that was used during this time for jewels, this is most likely Georgiana’s hair used for the ring. Bloodstone is an unusual choice for the ring’s engraving, A jasper of chalcedony, bloodstone is a green jasper with red inclusions of hematite. Since classical times, it has held various meanings; from having the magical qualities of invisibility, to making rain, solar eclipses and preserving youth. It is also the birthstone for March, and given that she has passed away on March 30th, may be related to that. Much of its style would resonate through to the 1870s, as it is a template for popular mourning style. Elements would change, but the swivelling bezel, the woven hair and plain border of the black enamel are primary elements to mourning jewellery.

Queen Victoria’s mourning ring for Albert in 1861, with photograph attributed to J.J.E. Mayall, shows the same style in its own contemporary setting. The black enamel over the band shares the same sentiment. With mourning jewels that have less elements to their design, there is a focus upon the subject who is being mourned. In this case, the photograph replaces the hair and the initials are across the shoulders of the ring, but the basic elements are all there.

Importance

To genuinely discover the meaning of a mourning jewel, one must look back into it history and the relevance of its subject. Was the person iconic and important in the grander scheme of society? Would that denote them to make an impact in society that would relegate their jewels to become just a souvenir, or something more? Perhaps the subject is just a member of society and the jewel is highly important to the person who wore it, but their impact in society isn’t beyond the family home. Sometimes a jewel transgresses these boundaries and it both important for its status in history, but also highly personal for the wearer. This ring does exactly that; providing a very modest representation of love for someone who had an influential presence in popular culture.

Because of this ring, Georgiana can be appreciated for so long after her death. Her imprint upon female empowerment, social change and intellectualism is profound and because of this ring, she will be thought of for generations to come.