Ecclesiastical Jewels in the Middle Ages

Piety and fidelity are the primary aspects of what drive the need for a memory of love. The idea of retaining a thought of a person or belief and wanting to contain that in a jewel of remembrance is integral to why a jewel was created in the first place. We need to attribute our sentimental items to a place, person, time or moment, then define the symbolism of that into the form of what our ideal memory should look like. We then present this in society and have recognition of this within society. All of these elements are important during times of governance and conflict, where a society needs an identity. An individual needs to either show their status within a culture or promote their culture to others, these are the elements that define the pursuits of living, be they for financial gain or connecting with others.

In the ring featured today, religious belief is the primary reason why the ring was purchased and worn. Dating from the 14th century, this ring has a history that predates the mourning and sentimental jewels that eventuated with the rise of the mourning industry in the 17th century. Much of the mourning jewellery industry was built through religious schism and the path to personal identity from the 15th century, but the nature of wearing a jewel in remembrance or a person or ideal is as old as humanity. The 14th century may have been a different landscape for the culture that created this ring, but it was still a time when people held strong beliefs and wished to display them.

MATER DEI MEMANTO (sic) (‘Mother of God remember me’) is what is written around the edge of the band in reserve. Several other rings like this exist today, notably those in the British Museum, found in Chesterford and another in the Norwich Castle Museum, which was found in Nekton, Norfolk in 1847.

As an adjustable ring, it speaks to the commercial sensibilities of the Middle Ages. Mirroring the same way that memorial tokens are sold to travellers today, these items were sold to pilgrims that would return them back to their parish. They were marks of status and piety that identify the communities of people who lived during this time.

The 14th Century

In the 14th century, the Papal/Western Schism divided the Roman Catholic Church between 1378 to 1417. In 1377, Gregory XI ended the Avignon Papacy, where Popes of the Holy Roman Empire maintained office. Clement V was given the Papacy in 1305, but declined to move to Rome, making Avignon the papal enclave. This was the beginning of the split that would promote challenge to the Catholic dominance and eventually lead to humanist thought in latter centuries. Cardinals decided to focus on installing a Roman pope, to which Bartolomeo Prignano, Archbishop of Bari, (Urban VI) was named pope. His opinions countered that of the cardinals and there was an election of a rival pope, Robert of Geneva (Clement VII), with a re-established court at Avignon.

Leading from the secular split, it was a matter of diplomacy that followed. Various countries held different allegiance to the separate popes, making a further delineation between countries even deeper. In Avignon, France, Naples, Burgundy, Wales, Scotland, Cyprus, Castile and Leon, all held their support. Italy, Poland, Sweden, Norway, Portugal, Hungary, Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, England Flanders, the Holy Roman Empire and Venice would support Rome. From here, people threw their allegiance to their nationalistically preferred pope.

Despite national influence in trying to resolve the issue, Pisan pope John XXIII convened a council to resolve the conflict, supported by Gregory XII, who was Roman. All stepped down, except for Benedict XIII, who was excommunicated. Pope Martin V was elected in 1417, ending the schism, but the Crown of Aragon did not recognise this, nor did followers of Benedict or Clement, who elected Antipopes Benedict XIV and Clement VII, yet Clement VII stood down in 1429 and acknowledged Martin V.

It’s the impact of this upon the psyche of the regular citizens of Europe that had the deepest impact. The highest achievement of living a pious life for final judgement and entering heaven became fragmented and controlled by clear self interest. In the wearing of ecclesiastical jewels, there is still a strong belief that there is a fundamental meaning to life. The following century would show the marks of how this led to humanistic thinking and challenge of authority, but at the time, generations had known religion as their source of truth.

When looking at the MATER DEI MEMANTO ring, its detail is not simply about piety, but about safety. It is a girdle design and its blessing from the Virgin Mary connects to pregnant women who wore blessed girdles to ensure a safe labour:

“Probably one of the numerous Relicks with which the monasteries and babies then abounded, and which might have been brought to the Queen for her to put on when in labour, as it was a common practice for women in that situation to wear blessed girdles.” – Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York: Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth: With a Memoir of Elizabeth of York, and Notes, Sir N. H. Nicolas, 1830

The dual meaning and genuine blessing is promoting a human focus, rather than simply being about the direct piety from the wearer to Mary. For all of the change and splitting of the Catholic Church, the faith in its figures was still the only way to ensure a safe and happy life.

Ecclesiastical Jewels

In the same manner that tokens of sentimentality would mark the passage of a 17th-19th century young gentleman during his tour of Europe during a Grand Tour, Roman Catholics would receive tokens during their travels to sites of Catholic importance during the Middle Ages. Often made from lead alloys or base metals, the Catholic pilgrims were sold at shrines, in the same way as the MATER DEI MEMANTO ring would have been. Their relation is part of the conceit of business, as where there is a market for piety, there’s an industry to accommodate it. This kind of jewellery transitioned into jewels of personal sentimentality, such as mourning, thought and loss, by the time of the 16th century Protestant Reformation. For more on the impact on life and jewels of this time, please read the following article:

> Culture, Conflict & Mourning in the 17th & 18th Centuries

“Pilgrims’ badges were, in their simplest guise, cheap tokens cast in lead or pewter, or stamped in tin or brass foil, which were sold as souvenirs at holy sites. They took the shape of an image or symbol associated with the shrine at which they were issued… The badges were believed to protect the wearer against evil. At a price range that was roughly equivalent to one-tenth to one-third of the daily wages of a Florentine mason for a dozen badges, they are…marketed… for consumers with a very small purse. With sales figures running into the hundreds of thousands, the Church can claim to be the first to have successfully exploited the economic potential of mass consumption.” – Viewing Renaissance Art, K. Woods, C. M. Richardson, A. Lymberopoulou

Cheap, mass produced badges were made by die stamping or poured into moulds, making them widely accessible to their audience. The prolification of such a strong identifying message only helps to propagate it. Commonly worn outside the clothing, at the neck or hat, they were important identifiers of religious status. In the same way that the monetary expense of an impressive jewel would show class status, these reflected back on the status of the wealth of the soul. For the sake of good luck, they were thrown into water, where many examples have been found, or displayed in the pilgrim’s parish after the pilgrimage; another mark of status for themselves and the parish.

As with all jewels that denote memory and love, the quality varied. In the above hat badge, the now missing gold loops would have sewn it into a man’s hat. Depicting St John the Baptist, this popular image was transferred throughout Europe in various forms of media c.13th century, when in 1202 the alleged head had been transported from Constantinople to Amiens, Normandy. As with popular movements through history and today, the level of interest sparked a cultural following that popularised the saint. This reliquary is of the similar intent as a pilgrim badge, in that it was a popular image, mass produced, but it is gold, cast and enamel, making it a status symbol as well as a pious one in the 1500-1552 period.

“One of the most important status markers for the poor was perhaps the pilgrim’s badge. The road of pilgrimage was open to all ranks, as inns and convents provided pilgrims en route with free accommodation. A pilgrimage was officially undertaken to fulfil a religious vow. By 1500, though, visits to renowned relics and miraculous mages had become a form of tourism. Paupers could even earn money by making the sacred journey on behalf of a rich person. Among the most popular destinations were the sepulchre of the apostle of Saint James in Santiago da Compostela in Spain and the Veronica in St Peter’s in the Vatican…” – Viewing Renaissance Art, K. Woods, C. M. Richardson, A. Lymberopoulou

In England, the site of St Thomas Becket’s martyrdom at the Canterbury Cathedral was a site of popular sales for these badges, exemplifying just how important these badges were to the local economy.

Other Materials

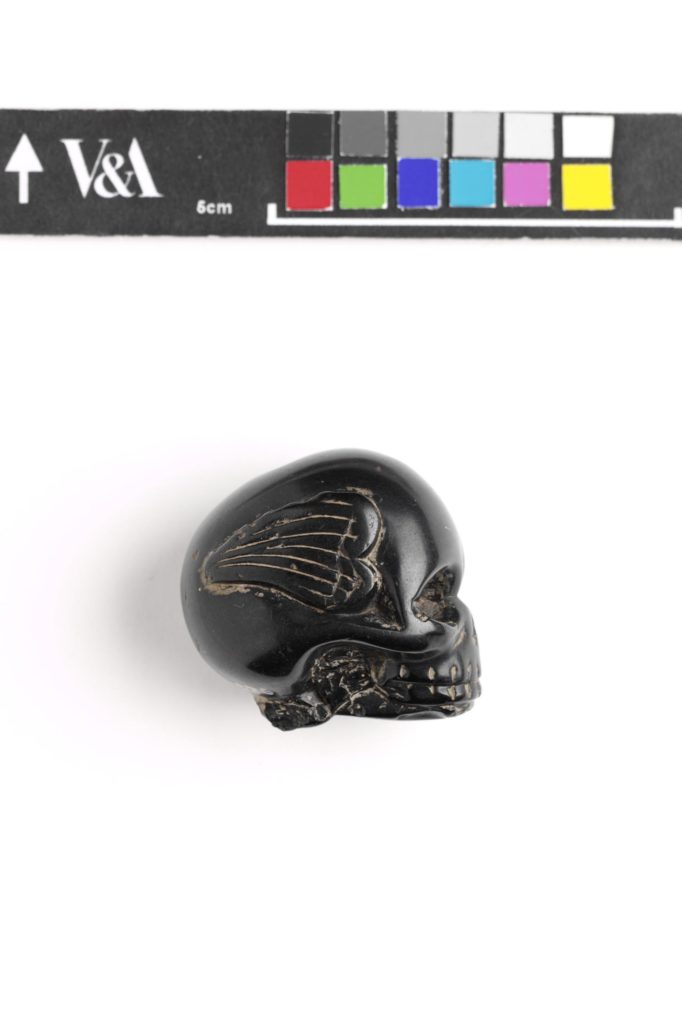

Jet was another popular material that would later be used in sentimental jewels of the 19th century, but it also had a popular past in the 14th century, contemporary to the MATER DEI MEMANTO ring.

‘It is black, smooth, light and porous and differs but little from wood in appearance. The fumes of it, burnt, keep serpents at a distance and dispel hysterical affections… A decoction of this stone in wine is curative of toothache…’ – Pliny, Natural History, 1st century AD

Jet’s history dates to the prehistoric, as it was a material used for various artefacts (amulets, shaped as animals, beads, combined with amber, bones, teeth, etc) dating back 10,000 years in the France, Germany, Switzerland regions. More complete pieces have been found from Yorkshire to Scotland from 4500 years ago.

Romans used jet for rings, bracelets, dagger handles, necklaces, hairpins and die and excavations have found workshops dedicated to jet production in York (Eburacum). Pieces of possibly York origin have been found and are on display in Cologne.

In America, Pueblo Indians (around the Utah and Colorado regions) produced jet jewellery, combining it with shell and turquoise, which, in light of the Spanish jet industry, pre-dates the Spanish arrival in the area.

As a popular and reasonably simple material to carve and construct items from, jet never completely disappeared as a usable material. It leant itself well to medieval construction, due to its properties of keeping away evil spirits and ecclesiastical jewellery used jet as a material liberally. As seen in the badges previous, jet’s use in items such as rosaries and tokens were prolific in the Middle Ages. By the 14th century, a jet industry emerged in, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany. Jet turners and carvers formed separate guilds, producing mostly ecclesiastical jewellery, declining only by the point of the Reformation.

Identity and Memory

Public ritual can often best be seen in the mourning of a monarch. The types of fashion that would have been emulated by the public, where possible, stems from the aristocracy down.

Richard II’s funeral in 1400 is an early example of how the various colours of mourning in dress could be displayed. White, gold and black are utilised, showing that there was no formal standardisation by the 14th and 15th centuries. In this funeral cortege of Richard II leaving Pontefract Castle, a washed-out palette of colour used in the display of the mourners adds an anaemic and sad pall to the painting. At St Pauls, thirty torch bearers wore white and the conventions of a monarch’s death were the most direct and ‘proper’ of what a nation would try to emulate for the ideal way of mourning.

Modern fashion, symbolism and colour theory have their basis in this period. New wealth that would emerge in the merchant class, the establishment of guilds and education would pave the way for modern systems of education, class and governance. Questioning religion and the established order were the primary theories on destabilising the old ways of how society operated.

In mourning and sentimental jewels, these values are highly important. Without the basis for a token of sentimentality, be it one of religious or personal piety, the jewels that became accepted for the memory of love and death could not have existed. Knowing that someone could be considered royalty or loved in a way that would have previously been valued for a religious figure have their roots in items such as the MATER DEI MEMANTO ring and pilgrim badges.

Fashion is a connection to the mainstream consciousness of connectivity within society. To wear something that identifies you as a larger part of society is the basis for a community. To wear something that denotes a special status of piety and respect only adds to that of the individual. Be it for the genuine love of God, the promotion of status or simply to start a story about travel, ecclesiastical jewels are as important as sentimental jewels for the Middle Ages.