Daisy Symbolism in Jewels

The Museum of Whitby Jet is a genuine establishment of living history. Combined with the store W. Hamond, it presents the oldest connection to 19th century Whitby Jet manufacture that still exists. It is a tribute to the 1500 men and 200 shops that existed in 1873 to produce the finest quality of Jet available in the world. Their craft, of carving, turning and polishing jet held a standard that set the British Empire beyond any other jet industry in the world, being held in the highest regard by Queen Victoria herself.

Due to the popularity of Whitby Jet, the instances of its carving designs are almost infinite. The Victorians relished the romantic and sentimental language of flowers. They were educated, had access to new wealth and were the first affluent middle class that could afford leisure time. Travel was a part of seasonal Victorian lifestyle and cottage industries emerged with the connection of rail lines that ferried these sentimental people across Britain. Whitby’s popularity as the centre of Jet fed its local community and its economy. Carvers were charged with appealing to the most popular designs from the visitors, who requested sentimental tokens to gift to their loved ones.

This Art of Mourning series is in partnership with the Museum of Whitby Jet and is a look at the jewels of the museum through the eyes of the Victorians who requested and understood the love language of flowers.

To achieve this, part 1 of the series is an introduction to Whitby Jet, which can be read below:

Link > Discover Whitby Jet

Part 2 is an understanding of ‘floriography’, a late 18th and 19th century attempt by philosophers and writers to connect floral discoveries of the world to emotion to empirical fact. This can be read below:

Link > Understanding Symbolism: Botany and Floriography

Symbolism of The Daisy

Plucking a daisy’s petal to the mantra of ‘s/he loves me, s/he loves me not’ is a pure expression of the innocence and hope that the daisy represents. Victorian fascination with the meaning of flowers, or ‘floriography’, is connected to society being well read, affluent and commercially sentimental. Gifting tokens of love was a common part of social etiquette, so a jewel created for a token of love and memory was part of everyday life. The Romantic movement was a connection for the Victorians back to the ideas of classical and medieval societies, which were considered simpler, more pious and virtuous than the urbanised, industrial society of the British 19th century. Bucolic vistas and floral emblems were adornments of architecture, fashion and jewellery, which all had their sentimental values connecting to the literature that the Victorians read.

A daisy represents the purity of innocence in their jewels, though there was a development of this through the publications of the early 19th century. Between 1825 and 1856, the flower’s symbolism developed into its final meanings, which were as varied as the number of petals on the flower itself.

Floral Emblems by Henry Phillips was published in 1825 and begins with outlying the flower’s classical roots:

“FABULOUS history informs us that the Daisy owed its origin to Belides, one of the nymphs called Dryads, who were supposed to preside over meadows and pastures. While dancing on the turf with Ephigeus, whose suit she encouraged, she attracted the admiration of Vertumnus, the deity who presided over orchards ; and to escape from him, she was transformed into the humble flower, the Latin name of which is Bellis. The ancient English name of this flower was Day’s Eye, in which way it is written by Ben Jonson; and Chaucer calls it the “ee of the daie.” No doubt it received this designation from its habit of closing its petals at night, which it also does in rainy weather.”

Phillips goes on to connect the daisy with a variety of poets, who used the daisy in their work, which can be seen below.

The Language of Flowers with Illustrated Poetry by Frederic Shoberl elaborated on this by adding meaning to the colours of daisies in 1839:

“The daisy (or day’s-eye) imports the pure virginity, or spring of life, as being itself the virgin bloom of the year.

The intermixture of nettles requires no comment.

Admitting the correctness of this interpretation, the whole is an exquisite specimen of emblematic or picture-writing. They are all wildflowers, denoting the bewildered state of the beautiful Ophelia’s own faculties; and the order runs thus, with the meaning of each term beneath :

Crow-flowers… Fayre Made.

Nettles… Stung to the quick.

Daiseys… Her virgin bloom.

Long-purples… Under the cold hand of death.”

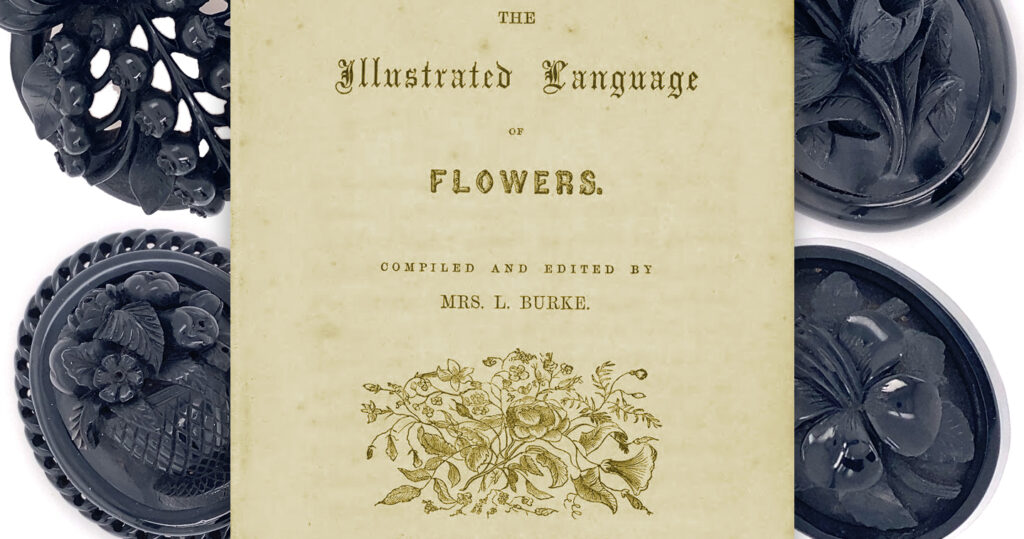

By 1856, the classification of the daisy symbolism and colour was outlined by Mrs L. Burke in The Illustrated Language of Flowers:

Daisy… Innocence.

Daisy, Garden… I share your sentiment.

Daisy, Michaelmas… Farewell.

Daisy, Party-coloured… Beauty.

Daisy, Wild… I will think of it.

Ladies etiquette books were an essential part of the middle class Victorian home, such as Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, and Burke’s book on flowers was a widely, and still, published guide to their understanding of floral symbols.

The common daisy is dedicated to St. Margaret of Cortona.

Double Daisy. – Bellis hortus.

Participation, or I partake your sentiments.

Daisy.— Bellis perennis.

Innocence.

Michaelmas Daisy.— Aster Tradescanti.

Cheerfulness in old age.

We present these flowers as the happy emblem of cheerfulness in old age, since, like

that blessing, it lengthens the summer of our days, and contributes towards the enlivening of all who compose its circle.

“ At sight of thee my gloomy soul cheers up ;

My hopes revive, and gladness dawns within me.”

A. Philips.

By the assistance of the plants of China and Florida, the reign of Flora is considerably lengthened in this climate; and the later months are clad with great beauty, whereas

formerly,

“ All green was banish’d, save of pine and yew,

That still l display’d their melancholy hue ;

Save the green holly, with its berries red,

And the green moss, that o’er the gravel spread.”

Floral Emblems Henry Philips, p. 90

DAISY.

INNOCENCE.

FABULOUS history informs us that the Daisy owed its origin to Belides, one of the nymphs called Dryads, who were supposed to preside over meadows and pastures. While dancing on the turf with Ephigeus, whose suit she encouraged, she attracted the admiration of Vertumnus, the deity who presided over orchards ; and to escape from him, she was transformed into the humble flower, the Latin name of which is Bellis. The ancient English name of this flower was Day’s Eye, in which way it is written by Ben Jonson; and Chaucer calls it the “ee of the daie.” No doubt it received this designation from its habit of closing its petals at night, which it also does in rainy weather.

The Daisy has always been a favourite with poets. Shakespeare speaks of it as the flower

Whose white investments figure innocence.

Star of the mead! – sweet daughter of the day,

Whose opening flower invites the morning ray,

From thy moist cheek and bosom’s chilly fold

To kiss the tears of Eve, the dew – drops cold,

Sweet Daisy!

LEYDEN.

The daisy (or day’s-eye) imports the pure virginity, or spring of life, as being itself the virgin bloom of the year.

The intermixture of nettles requires no comment.

Admitting the correctness of this interpretation, the whole is an exquisite specimen of emblematic or picture-writing. They are all wildflowers, denoting the bewildered state of the beautiful Ophelia’s own faculties; and the order runs thus, with the meaning of each term beneath :

Crow-flowers… Fayre Made.

Nettles… Stung to the quick.

Daiseys… Her virgin bloom.

Long-purples… Under the cold hand of death.

Daisy… Innocence.

Daisy, Garden… I share your sentiment.

Daisy, Michaelmas… Farewell.

Daisy, Party-coloured… Beauty.

Daisy, Wild… I will think of it.

Unto the lily, vestal of the dell,

Or daisy, the pet child of poesy,

Or lie beside some mossy forest-well

Companion to the wood anemone.

Howitt.

The Illustrated Language of Flowers, p. 19