‘Come Ye Blessed’ – A Memento Mori Ribbon Slide and Memento Mori Evolution

Memento mori and its adaptation into jewellery and accessories is a unique look into how human behaviour and identity. Throughout the early-modern period (post 1600), we have been looking to find the ‘truth’ to existence and what happens when we finally cross over into the ‘afterlife’. But it is what that afterlife truly means which inspires art and much of how we create our trappings.

Intelligent systems of control, be it government or religious body, know how to use art as a dominant power. Subjugation through opulence and awe are what can be bought through wealth, things which higher levels of society have. This promotes a structural culture which can have levels; these levels look up towards the next.

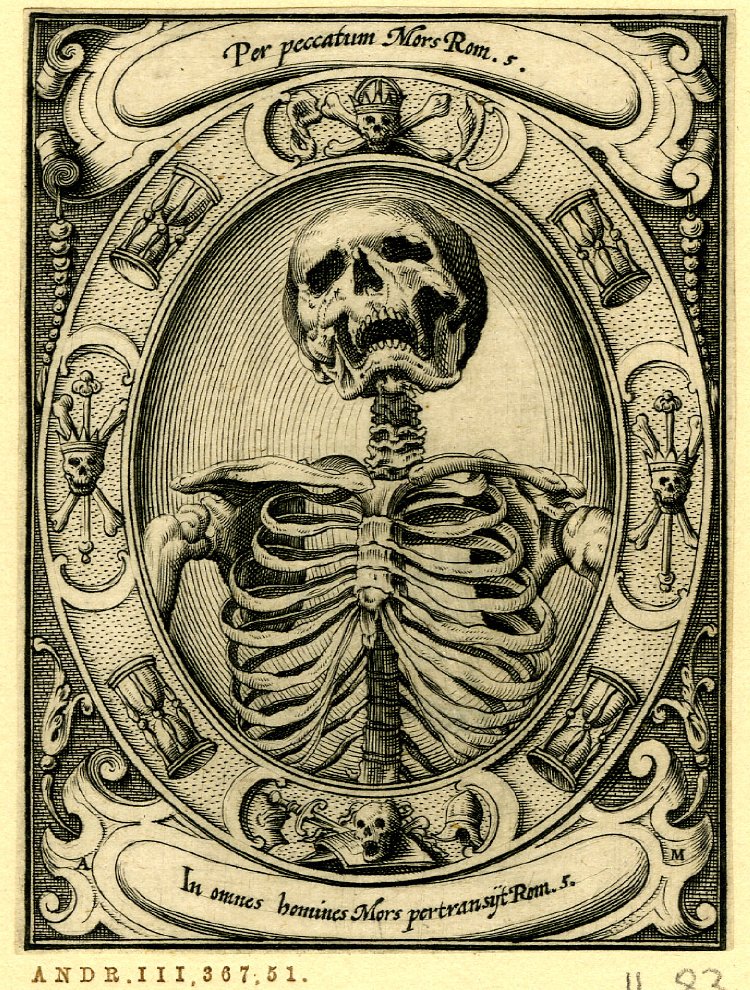

While design, such as Baroque, can be dominant in its grandeur and glory to provide this awe, nothing speaks louder than the symbols of memento mori. Memento mori is the literal depiction of death and decay, showing blatantly that life is fleeting and a person will be judged. Human adaptation of this art changed throughout the years, specifically from c.1400-1900 as our philosophies and technologies changed around us.

For these reasons, it’s best to analyse a jewel from its top-down structure. What was the dominant force at the time which needed fashion and art to control a society? What were the reasons in history which created discourse and affected a society which would be trying to gain solidarity and community? At the highest of levels, these factors need to be considered, then we can understand why a jewel is created in a particular style.

Death and decay are naturally fearful for our mortality. Presenting these symbols in context with fashion only amplify this message and create a level of anxiety about how to spend time; be it for the benefit of the self, church or crown. Time is fleeting, as the ‘tempus fugit’ Latin phrase often suggests in memento mori jewels. How memento mori is used as a fashionable affectation depends upon the wearer from the earliest of periods through to the Enlightenment. At one stage, it was a literal fact, in the other, it was about self-awareness. These two different opinions speak towards the afterlife in a way that’s unknown and judged. If one is unknown, then it is best to maximise the passage of life into a superior place and aspire to a new level, in the other, it is to work harder in order to be judged fairly and join the family on the other side. These values are personal and related to the family.

Culturally, the Protestant movement created wide discourse and challenge which could allow thought surrounding the individual. Traditional concepts had been destabilised since Martin Luther wrote the Ninety-Five Theses in 1517. The challenge to ecclesiastical thinking and its establishment of the Protestant Reformation had effectively enhanced the artistic value of English jewels through the Huguenot emigration and the goldsmith knowledge that they bought with them. This was 1686, from the revocation of the Edict of the Nantes and over a century since England had split from the Catholic church (1529-1537). Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought.

The ‘Western Schism’ or ‘Great Schism’ from 1378 to 1418 effectively split the Catholic Church, with numerous people vying to claim the true papacy. The end of the Avignon Papacy came on January 17th, 1377, where Gregory XI returned it to Rome. A year later, Gregory died, causing a Roman riot to ascertain that a Roman was going to be pope. Pope Urban VI, born in Bartolomeo Prignano, the Archibishop of Bari was elected, causing destabilisation due to what was considered outbursts of temper and a reformist. Robert of Geneva (Pope Clement VII) was elected as a rival pope on September 20th 1378 and established a court in Avignon. While there had been challengers to the papacy before, this was a schism by the leadership of the Church and a true break down of their process.

Breakdown in religion is the first factor in the destabilisation of a society. Any indoctrinated form of rule can create its own style around it, making symbolism identifiable and ubiquitous. When symbols are easy to understand, their language transcends words; they are visual markings of status and community. In the above rock crystal carving c.1450-1500, the depiction is the face of a young woman with hair parted in the middle on one side. On the other side is a death’s head with the lower jaw broken away. What is nebulous is the reflection of the eye sockets aligning to the girl’s eyes perfectly, showing the decay and mortality of life. If this was on behalf of the artist or not is lost, however, what is important is that this carving was from France in a period following on from massive questioning of religious legitimacy.

For France, the Hundred Years’ War had lasted from 1337 to 1453, with the House of Plantagenet war against the House of Valois. This is effectively the rulers of the Kingdom of England vying for control of the French throne. Throughout the various rulers that lasted until its end, the mortality rate was something which required a populace to consider its reason within a hierarchy that used it to live and die by its own command. With this insecurity in both government and god, an introspective reflection on what mortality meant became important.

A crystal keepsake of this fashion isn’t just a nice piece of fashion, it’s a keepsake that could be held to remind oneself of the very act of mortality itself. Tokens of seeming mortality are affectations; they’re not religious statements of identity, nor do they hold a function. This is to be kept as a statement of living and that is where the birth of memento mori as a concept stems from. Memento mori speaks to clearly to the nature of existence, rather than being a simply morbid endeavour, it’s a statement to try harder and achieve more in life. Fashion is never arbitrary; it’s what humanity aspires to be within society and what we identify as being something better. Be it taken from a monarch or celebrity, the values of aspiration are within body language, hence when a person carries something so blatantly relating to death, it’s statement reflects back on society itself.

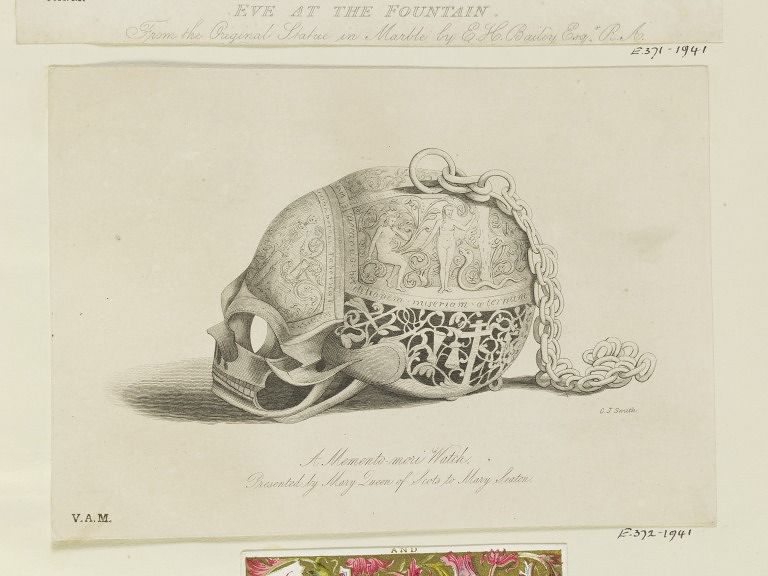

This above coffin from 1540 is a continuation of the above crystal head. Purchased in 1856 by the V&A Museum for £21, the piece was considered to be found on the ground of Torre Abbey, Devon. Henry VIII ordered the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s, yet this jewel is from just afterwards, when the abbey was converted into a private house. The assumption is that this comes from the Cary family who lived in the house from 1662 until the early 20th century.

Several elements can be taken from this pendant’s construction. The first is that post 1662, there is solidarity in England, internally. To have a family be so held to such a specific property from the 17th to the 20th centuries shows establishment of a central government or crown.

Otherwise, the jewel itself is a basic establishment of what mourning jewellery would become. The industry of mourning hadn’t begun until the 1680s and the Industrial Revolution which could mass produce (or at least increase) jewellery and textile production.

The skeleton it literally depicted within the grave; the lid itself is heavily decorated with medieval and Celtic design patterns. Even the skeleton looks not directly at the viewer, which would indicate upwards to the heavens, but north. Its hands cover the middle-section and not the folded over chest style which shows some modest in the design itself. It is an exquisite piece that details all the affectation of personal sentimentality in death and life; a sentiment of using art as an affectation of death that would relate to what artists interpret within their own art.

Consider how visceral this print is from 1605. Compare it to the below painting from 1667. This print is from Germany and the below is from Amsterdam. All the elements of memento mori are displayed here in perfect display and design. From despair in the visage of the skeleton (reflected also in the 1540s pendant), the tempus fugit symbols are all complete and seen in jewels and art even today. The transition from the 16th to 17th century marks a change in how the wearing of memento mori evolved from more intimate items reserved for high status in the aristocracy to more attainable jewels and items that were being appropriated for mandated periods of mourning.

As the 17th century turned, there was a marked change in how death was interpreted in jewels. Mourning bequeathments had been in popular thought since the late 16th century, but became indoctrinated through the 17th century. Most famously, William Shakespeare in 1616 declared that in his will that his daughter and wife should have rings stating “Love My Memory”. Samuel Pepys bequeathed 123 rings upon his death in 1703. These rings were graded into three classes and given out according to proximity of friendship and social status. So typical as a token of giving at a funeral, Pepys wrote in his diary:

“This day my Lady Batten and my wife were at the burial of a daughter of Sir John Cawson’s and had rings for themselves and their husbands.” – July 3, 1661

There is a change in society which could afford jewels created at an attainable cost.

As memento mori starts to permeate the understanding of symbolism and go beyond just the literal form of decay, it begins to enter the understanding of what it means to live as an individual within a society. As stated, Martin Luther wrote the Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, questioning ecclesiastical thinking. This led to the Protestant Reformation, creating enough discourse for Henry VIII in 1534 to separate the English Church from Rome, which had no single catalyst, but a series of events (being Henry’s annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the English Reformation and Lollardy). For each reason, the period of the 16th century to the turn of the 17th century saw an establishment across Europe of a concept surrounding mortality and life. For a time when ecclesiastical figures dominated art and chastity and utilitarianism defined the nature of lower/middle class costume, challenge to defined groups within society was acceptable.

While jewellery is worn art, painted art is what we look towards as the first catalyst of style for its time. In this oil painting by Jacob van Walscapelle (1644 – 1727), the nature of memento mori within the wilted flowers is clear. Allegorical statements of the early modern era needed to relate toward Christian paradigms, hence this painting has the wilting bouquet of flowers and a wheat stalk with insects in the blooms. The wheat, being the basic ingredient for bread and the grapes, producing wine, are an elusion to the Eucharist. Butterflies here are considered to be a metaphor for the resurrected soul and the wilting flowers are a vanitas (memento mori) reflection.

So there is a marked change in the way that memento mori had entered the popular mindset. Now, bequeathments in wills to use the symbols was not unusual or uncommon; the representation of human decay only amplified the message of how time flies and that humanity ends with the investable death. With that in context, larger items could be worn around the person and show the memento mori affectation in proud fashion. This watch, made by J C Vuolf, was made in Germany c.1655-1665 shows the human skull in a silver case with the lower plate/jaw hinged at the back. On top is the winding hole and a silver hanging loop. The watch is inscribed with:

vita fugitur / life is fleeting aesterna respice / look down upon a fallen thing caduca despice look upon eternity incertita hora / death/hour is uncertain

Consider that these statements were worn in a very public way. There’s no allusion to the motifs of memento mori, rather, they are emblazoned as a statement of living for the wearer.

The watch was a great catalyst for the advent of the popular wearing of the chain. From the time of Henry VIII, wearing a watch as a pendant near the waist became a fashion. On January 1-2, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the noted diary writer wrote on January 1-2 1668 “..and took coach and home about 9 or to at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing…”, indicating the importance of status to wearing such a timepiece on the body. Affluence in the timepiece demands an equally adorned chain to hang it by. By the 18th century, the waistcoat/bolero was the popular form of wearing the watch, diagonally across the body.

While the chatelaine was also worn with equality between men and women; its development and craft lent by the influx of Huguenots emigrating to Great Britain. This influx created new skills through which finer jewels could be produced. In the case of these watches, however, their importance to making a personal statement is as bold as the Neoclassical period and its adherence to classical art, culture and fashion. The larger a jewel or accessory can become in fashion relates back to the individual’s personal statement on living.

Watches and clocks with the memento mori motifs were not uncommon, dating from the mid 17th Century to the 1930s. This early Verge silver skull pivots at the top of the cranium, whereas others pivot from the jaw. There are others created that fold open at the top of the head with enamel and diamonds, but pieces like these are extremely rare and command a high price. Examples exist from Switzerland, France, Germany and England. As written by the Taft Museum:

“The skull and watch are part of the standard subject matter of 17th-century vanitas still lifes. Vanitas is from the Latin for “emptiness” or “untruth,” from which comes the English word “vanity.” Such pictures depict objects that have an underlying moral message—usually about the fleeting nature of physical reality. Therefore, it is not surprising that the skull and watch, two reminders of the passage of time, should merge in a single object. The use of the skeleton hand, however, is unusual.”

Vanity is a wonderful term to consider memento mori of the 17th century. It reflected back on the lifestyle and politics of the wearer. Utilising these elements of death or love had previously been relegated to those who could afford the affectation in fashion, but now, there was an element of society that existed which could live for the pursuit of philosophy and challenging thought.

The evolution of memento mori would not have been possible without the political and social turmoil that resulted from the Schism and destabilisation of governments. Wearing a jewel or accessory from the 17th century onwards only added to the convictions of what the wearer felt, be that a move away from the Catholic Church or an alignment towards it. For example, the below ring would not have been possible without the establishment of the Church of England:

The concept of death being a factor that can happen at any moment is a message to the wearer or viewer of the symbol that life must be savoured to the moment and that final judgement awaits all. It is part an ecclesiastical statement as well as one of the intellectual and aristocratic, who could afford to adorn themselves with the memento moro symbolism. It is a statement that is ancient, with Roman depictions of memento moro joined with statements such as ‘Eat, drink, be merry, for tomorrow we die.’ Catholic domination during the middle ages utilised the memento mori symbolism greatly, instilling the values of being judged for the life you lead. Sentiments such as ‘Dye to Live’ inscribed within a memento mori ring adds to that statement, for the afterlife is the true essence of being.

Following the Restoration, Great Britain had suffered a shock to its primary values of religion and politics. In the space of three generations, the Catholic Church and the Crown had been destabilised, with the Restoration of the Crown building around a new society with new values of the ‘self’. This didn’t take away religion, but questioned the purpose of living, bringing back many of the life statements surrounding memento mori. Intellectuals and the aristocracy could wear jewellery with the memento mori symbolism and show their pursuit of a better physical existence. Jacobite (Latin: Jacobus/James) rebellions continued between 1688 and 1746 were instigated to restore Stuart kings to the thrones of Scotland and England. James II and VII was deposed in the Glorious Revolution in 1688. James was considered to be pro-French and Catholic, leading to William III of Orange to invade from the Netherlands. James was succeeded by William III & II and Mary II, who were married – Mary being joint sovereign of England, Scotland and Ireland. Mary II passed on in 1694, William became the singular ruler. Throughout the shared reign, the Jacobite resistance promoting the divine right of kings challenged the rule, stating that the throne is a rule of God and not dictated by Parliament. Over 400 clergy and many bishops of the Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church refused to take an oath of allegiance to William. Parliament majority of the Whigs supported William, with fluctuating support by the Tories. Wars against the Louis XIV of France kept William away from England, during the time when Mary was alive, letting her govern, wasn’t resolved until the Treaty of Rijswijk ended the Nine Years’ War in September 1697. This statement of authority in William from Louis as monarch pacified the Jacobites to some degree.

With this affectation, the symbols also continued their meaning of mortality and their use in mourning jewels grew as the mourning industry grew. In the piece from c.1600, there is an early representation of the skull in an Elizabethan design. This is the nexus between the change of the symbols being decidedly mourning and previously for the statement of living.

It was the popularisation of crystal, commonly known as the ‘Stuart Crystal’ c.1603-1714 in England, during the 1680s, which popularised the look of memento mori symbolism. Seen most commonly in rings and ribbon slides (worn at the neck or cuff), oval shaped bezels with faceted crystals reflected the light in the same way as a faceted diamond would. Underneath, gold wire cypher initials being flanked by memento mori symbolism and placed on top of hair, material or vellum was a way to display identity and relationship status through a jewel on the self.

Baroque influences upon these jewels began to enter through the 1680s, but became more common at the turn of the 18th century. Shapes became more rectangular in brooches, slides and bezels, with sharper facets between c.1700-1720. Memento mori symbolism was adapting to the new styles and were the main designs for mourning representation. Objects of the body or the afterlife to denote mortality were flanked with Baroque design elements through floral motifs, such as the acanthus entwining flowers. Much of this is a reaction to the dominant architectural styles seen in other physical designs, which leads the jewels to adapt to fashion.

Romantic influence in contemporary sentimental jewels led for the heart motif to become popular and influence the worn statement of love for a jewel. Most popular being the ‘Georgian Heart’ motif, which can be seen below:

Following this, the Rococo period used the existing memento mori/Baroque styles and morphed them into a much more elegant and organic design. Bands became highly decorated and twisted into ribbon/scroll motifs, the infusion of greater floral elements was an adaptation of the dominating Baroque style and the bezels on mourning rings became smaller. It wasn’t until c.1765 and the introduction of the Neoclassical period that the greatest challenge to the memento mori style would essentially relegate it to become an anachronism.

Wearing a jewel to show that you will be judged and to live life for all its benefits is quite a grand statement during times with high mortality rates and a more feudal-based system of government, but during the 1670s-80s, there’s a strong shift to higher industry, specialised work and education. Politically, England was recovering from a civil war and the reinstatement of the kingship in Charles II in 1660, the Great Plague of London in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666. There was a high mortality rate and Charles II was only beginning the process of the Restoration. Hence, pieces like this could allow themselves to become more commonplace, the symbols of death could be appropriated for an industry that was reacting to the execution of a king and a subsequent civil war, it could pick up on the nuanced tokens of affection that became popular from this and it could produce a product that was relatively easier to produce and almost the same to sell.

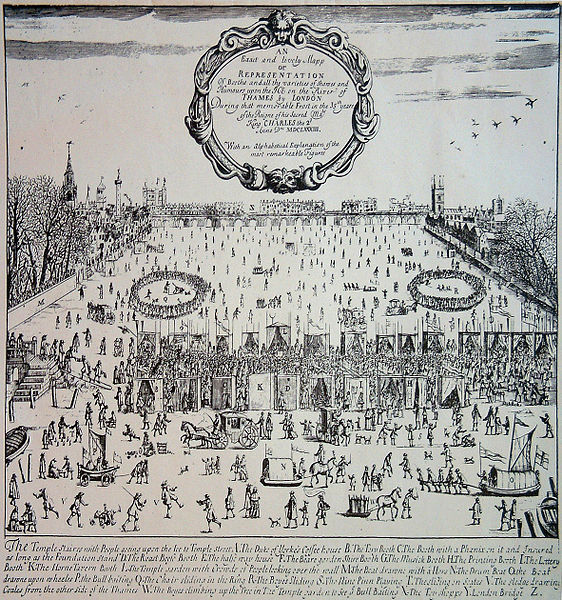

Several events during the reign of Charles II led to the jewels of mourning and affection that dominated through to the 19th century. These being a combination of the Great Plague of London in 1665, with a mortality rate of an estimated 100,000 people, causing the king to flee London to Salisbury in July 1665. The Great Fire of London in September 2nd, 1666 was another such occurrence that, while not causing the high mortality rate of the plague, decimated London (13,200 houses, 87 churches) and left a lasting impression on a culture that had been challenged through political and religious thought.

Combine with this a period of cold, during the “Little Ice Age”, where the River Thames frosted over. One such notable event was the Great Frost of 1683-84, with a two month frost that led to 11 inches of ice depth in London. Connection between communities was advanced through the use of written language, particularly that within chapbooks. Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written in jewels, particularly inside posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content.

Society was at a point where events had overtaken the immediacy of global rule and communications that didn’t end at the limit of a village. Now, the world had opened up in ways which forced society to accept the relationships developed on a personal nature to be the truth, beyond religious or crown judgement. In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

As the Protestant Reformation was such a reaction to the Catholic Church, the Baroque style was encouraged from the early 17th century as an emotive way of influencing and dominating art with religion. It is an imposing style, particularly in architecture, with an opulence and power that seems all pervasive, particularly when used in context of religious places of worship. Between the mid 16th and 17th century, this ring shows the influences of different socio-political influences that have led to its dominant memento mori motifs. from the Restoration and the reign of Charles II, there was no period of absolute peace, but this did begin a period of challenge to traditional thought and the rising of new industries. These industries could capitalise on new technologies and learnings of introduced talent into Britain and exploit this for financial gain. Death and taxes being two of life’s absolutes lead to a good profit being made from the act of grief and the requirement of presenting oneself in public with the trappings of grief when a loved one has died.

Combine the mortality rate in the mid 17th century to be around 40, with even childhood being difficult to survive and the message of this ring shares its honesty. Life was difficult and there were many opportunities to fight for a political ideal and get monetary rewards, which allowed for sentimental jewels to flourish. Capitalisation on these causes, as well as the various disasters, be they natural or otherwise, only played to the heart of love itself. As a population, we require the company and love of others, as well as their support. Without giving thanks to this concept in a ring or jewel, then the connectivity between societies and cultures does not lend itself to memory and learning through what has come before. If not for the generation that enabled the Protestant movement, then all that had been in the latter 17th century would not exist.

Resonating mortality for its time, this skeletal ring was at the height of its fashion and its sentiment. Surrounded by turmoil, yet reflected in love, the ring reflects several skeleton motifs and the desecration of the body. Why this was such a popular motif was the immediacy of death to the wearer and the viewer of the ring. At no stage is there any consideration for a beautiful life after death, or that the mourning is a sad occasion for opulent decoration – memento mori presents death in its basic fundamental. Remember you will die, this ring tells us.

And so, the Stuart Crystals and the memento mori style become engrained within the mindset of modernity and the collector. In the above example, there is a box made of silver, combining several crystal slides and pendants. Though this box quite possibly stemmed from the 18th century, it shows just how the appreciation of the memento mori style had settled in a historical-looking context. These aren’t contemporary or built around a family, they are appreciated for their historical context even so close to their construction.

Compared to the pieces from the 15th and 16th centuries, they have an immediacy to their lifespan. They are built around the nature of death and judgement as a value, not as a requirement or as simply art. Vanity they may have become, but they are truly jewels of their time.

Holistically, what can be gathered from the combination of values from the 15th century to the 19th century? Society had come a long way and with standardisation of of symbolism due to mass trans-continental transit, colonisation and exchange of ideas and values, many of the barriers that had been through phases of discovery, conquest and rebellious identity establishment created a system of standardised symbolic value. Considering that the earliest examples seen in this article relate to Western society being confused by the turmoil of ‘people’ challenging for seats of power that were considered to be ordained by ‘god’, then the value of what that meant became less important. Value of living became more important and that value led to the representation of death as a very physical reality. Every day above ground becomes a great day and one of self/family improvement.

The Roman Catholic chapel found beneath the Cemetery Church of all Saints in Sedlec, Czech republic, contains an ossuary of an estimated 40,000-70,000 people. A popular burial ground, it grew in notoriety after the abbot of the Cistercian monastery returned from the Holy Land in 1278 with earth from Golgotha and sprinkled it over the cemetery. It was used heavily during the Black Death and the Hussite Wars, yet the ossuary was built c.1400. Ossuaries are not Western inventions, nor are they bespoke to Sedlec; resting places for human skeletal remains are typical when there is little burial space. It is what was done at Sedlec by František Rint under order of the aristocratic Schwarzenberg family in 1870, which is most interesting. The interpretation of the ossuary as a work of art; utilising skeletons to construct candelabras and decorations is a reflection on the 19th century manufacture of death. It was a product of what had come before. Since the introduction of the memento mori concept and how it related into art, the elements were used to instil a sense of direct understanding of death and life. By the 19th century, it had become art for the nature of art. It’s not a simple devaluation of the human remains that created its art, but it is focused on the art primarily, whilst early memento mori (particularly jewels with hair and remains) are directly respective of an individual.

By the late 19th century, the symbols of memento mori had become anachronisms, removed from the simple statements of ‘IN MEMORY OF’ and black enamel. Showing a skull in its place wouldn’t be considered tasteful for its time, which makes elements of art that utilise this interesting. How were they depicted in society and how does society treat these fringe elements? The ossuary at Sedlec is a good example of what can come from this, but how this reflects in jewels is far more difficult to gather, as the memento mori symbols had become to be more appropriated by fraternal societies.

Memento mori needed to adapt as new styles came along. The reason for keeping a consistent mourning style over the period of the middle 17th century to the 1760s shows a society that is adapting a style, but not revolutionising it. The symbols of memento mori would not and cannot go away; they are integral to our very identity, however, when that identity changes through a radical change in self-perception, the symbols take on a skewed meaning. Archaeological excavation was also another important element to the growth of classical culture in the 18th century. Pompeii and Herculaneum had discoveries in 1711, but resumed with major excavations in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians. The ‘Grand Tour’, a social institution since c.1660, was an upper-class, male rite of passage which the tourist would be taken by a tutor, servant and a coach, through the Alps, Seine to Paris or Rhine to Basel. Switzerland would be next, with a trip through to northern Italy and down to Naples, then through to Germany and back across to England. Each of these places was held in educational regard. Elements from history or cultural education (fencing, mountaineering, history, riding) were all absorbed from the relevant societies. Tokens from the Grand Tour were common to return to England with, such as the pendant below, which shows the elements of mortality:

With the archaeological excavations, one can imagine the surprise and delight of discovering the classical heritage which could be taken back to their homelands and recreated for modernity. Herculaneum was described by Sir Horace Walpole as ‘a whole Roman town, with all its edifices, remaining under ground’, meaning that a pristine site of research was offered to modern craftspeople to replicate or be inspired by. Architecture is one of the most persuasive and organic styles of design that permeates culture. Architecture is grand and dominating, not allowing anyone to pass by it without noting its style. When architects such as Robert Adam used the past for aesthetic taste, classical influence in Scotland and England could not be stopped. In 1748, Giovanni Battista Piranesi began etching classical structures and in 1755, Adam on his Grand Tour met Piranesi met, allowing Adam to return with further inspiration in classical style.

The Neoclassical movement had effectively revolutionised the memento mori statement in fashion. Gone was the need to have skulls and crossbones proving a grim outlook into the afterlife, introduced were classical allegorical depictions of love and grief to show a connection to the Greco-Roman period and remove the ecclesiastical nature of judgement. Note the above miniature and how the mourning style was perfected for Neoclassicism in the 1790s. All the elements, such as the mourning female, the child’s soul, tomb, willow, cypress and angel are all pristine in their style. There’s no questioning its style for the time; it had replaced what would previously have been the skull, hourglass and scythe. But were these symbols completely gone from mourning jewels? In the following ring from 1780, there is a complete combination of the various symbols from memento mori to Neoclassical:

This brings us back to the primary themes of the these pieces and that is; what is the nature of the symbolism, why is it used, why would it have been commissioned and how would it have been worn?

Firstly, let’s look at the facts. The ring is dated 1780 and dedicated to Anne Staneway Obt 8 Mar 1780 AE 20. There is white enamel, domed crystal, the sepia painting and high relief tomb motif with the skull and crossbones on top, painted on the tomb is ‘tempus fugit’ (or ‘time flies) as the winged hourglass . There is the willow, cypress and all this sits underneath a piece of domed crystal. The bezel measures 3/4 inch by 1/2 inch and the band is 1/8 inch wide.

Judging from the construction, this piece is in quite original condition. Much of the time, sepia in such fine condition has been doctored with pieces today in order to repair or fetch a higher price, also, the crystal is another telltale sign that there has been some repair work. Often, glass has replaced with bevelled edges, as it’s much harder and more expensive to replicate this. From this piece, right down to the wear of the white enamel, it’s as it was and as it should stay. Visually, to see the richness of the white ivory and the enamel together really make the sepia and high relief gold/hairwork pop out at the viewer. This piece was made at a time of experimentation with the Neoclassical style, so much of these practices were still being understood before they became common in production. What we have is a piece of exceptional quality and that speaks to the family that produced it. Their value system of utilising these elements may be their religious identity being displayed within the jewel.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, the memento mori motifs were appropriated more for their fraternal society connotations, rather than being a reaction of the Gothic Revival period to use in mourning jewels. Mourning jewels were utilising the basic elements of the Gothic style; bold enamel and decorative fonts stating ‘IN MEMORY OF’, which morphed into the Rococo Revival style, but never went back to the symbols of death. As in the above ring, some pieces do exist with the anachronistic memento mori symbols, but they aren’t the elements that are immediately identified within society.

Here is where we look at the piece and say that, underneath its age, we have a silver (unstamped) piece with ruby eyes, so it obviously wasn’t on the bottom end of when it was made. We can make assumptions of the 1880 period and the swing towards silver as a popular material and thusly look at the resurgence of the memento mori symbolism during that time as affecting this piece, or we can look to the previous century and assume that this is not about a dedication or memorial, but a trinket of mortality for a gentleman on a ‘grand tour’ of the continent. This would facilitate the use of the silver (rather than gold) and be an appealing gift.

The skull is the most revealing aspect of the piece. This is mostly due to the symbolism – it’s not simply the skull, but the skull and crossbones. Its style is incredibly simplistic and naive, without a clearly defined style of skull or bones, which leans towards its being more trinket-based, rather than a fine, bespoke piece of jewellery. Grooves over the eyes and the large nostrils defy the 19th century and onward styles that craft the well-defined skull and the motifs that we recognise mostly today. That is, however, not taking into account the memento mori revival period of the latter 19th century (which was not ubiquitous, but certainly a prolific niche) which used silver to make pieces like this and other peripherals, such as walking stick handles. This style, popular in the UK, was also consistent through France to Eastern Europe and remained to before WWI.

Fraternal Orders are the other, more common, bodies that appropriated the skull and crossbones motif and this particular pin aligns closely with Mason styles that can be seen here. With this pin, the addition of the crossbones does skew towards a Fraternal derivative, as this defies the simple skull.

For such a little ribbon slide, so much can be seen about memento mori and its evolution. To simply state the fact of what this jewel meant would be a disservice to its time and creation. Memento mori, while desirable for its literal depictions of mortality, are still elements that are very personal to identity. Be it for mourning (as in this case with the hair woven underneath, the enamelled skeleton and trumpet putti), or for a statement of living, these jewels formed an identity in a very transitional society.

Though death does not represent each piece, they all are built around the inevitability of death. This understanding of relishing the moment is one that should never be lost on a modern society, as it breaks us free from our political and social constructers and leads us to aspire to more.