Children in Mourning

A child in mourning is the ultimate symbol of family grief. The child is what carries forward a memory and validates the parent’s existence, so it is with great grief that the loss of a child could be worn as a jewel or in fashion. In the reverse of this, a child in mourning for a parent or relative brings the individual back to the reality of what death was. In modern society, death is desensitised and removed from immediate reality, while in the pre mid-20th century, children were very much involved in death and mourning ritual. The development of fashion around death begins with the child and the realisation that time is fleeting, so in this article, let’s discover how children’s costume developed in fashion and how parents produced jewels to deal with the loss of a child.

Children were part of the mourning ritual in the same manner as adults. From the perspective of costume, children were required to follow the stages of mourning and wear the appropriate garments and also attend funerals. For twelve months, children were required to mourn a parent, with the first six months in dull black or crepe to show deepest mourning. For the following three months of this period, the Ordinary mourning phase meant that they could wear black silk without crepe. For the final three months, children were allowed to wear half mourning colours. In General Court mourning periods, children wore mourning according to the mandated requirements, as well as for all relatives.

‘The Tolling Bell’, a hymn published by S.P.C.K in the 1840s, has an illustration of six girls carrying the coffin of an infant to the grave site. The girls are wearing white to denote the innocence and purity of the child in the same manner as white enamel would be used in a mourning ring:

The black ribbons that the girls are wearing denote grief, as would black enamel in a jewel. The proximity of children to mortality previous to the mid 20th century was far closer to the fact. Death was a part of life, rather than being disconnected through funeral practitioners who handle the body after death. Funerals began with the home, often with the body lying in state, forcing children to deal with the reality of death and practice the art of mourning.

It was until the 1760s that children wore mourning clothes that were identical to that of adults. The 1760s saw a change in cultural identity through the Neoclassical era, which resulted in diversity of fashion as Western society connected itself back to Greco-Roman identity through the Enlightenment. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and religious thought.

Leading to this period, children’s mourning mirrored that of adults. Sir David Owen’s will of 1529 stated ‘To make gownes and hodes after the maner and facon of mourners’, which holistically covers both adults and children with uniform mourning costume. To be even more specific, he stated that ‘I wille that everyone of my children have gownes and hodes of black clothe’. This is an early-modern example of how mourning was represented in society. Hoods and gowns of black cloth are established in the modern mind as the identity of mourning, relevant enough for everyone to participate in and wear.

In the 17th century, the covering of black crepe was typical in mourning to promote a specific shape and identity of mourning. In the German funeral of George II, Landgrave of Hesse, young boys in the procession wore tall crowned hats with long falls and full length cloaks in the same manner as their adult relatives. The investment in good quality crepe continued through the 17th and mid 18th centuries, causing an elitist view of mourning within society. 17d (pence) a yard of crepe in 1685 was the cost and this was high expenditure for the amount required in the costume.

Though it was the Neoclassical period which saw a change in mourning costume from the equality is costume that parents and children shared. As stated, the 1760s saw a massive change through the Enlightenment towards a humanist movement that focused away from the ecclesiastical, or faith-based, views on mortality, and put the responsibility of living upon the family and the individual. During this post-1760 period, girls would wear plain silk or muslin dresses with wide sashes. Boys wore ‘skeleton’ suits with soft falling frilled collars. Under the age of six, white dresses were acceptable for boys and girls, even under deepest mourning. As the formality around female dress declined, children’s dress would follow several years later (often ten years). This was a reaction from the mother to child and, in the 1770s period, part of personal liberalisation.

Throughout the 19th century, black was still the standard of mourning, particularly for children over six, and highly required for girls. Boys would have worn white dresses trimmed with black until the age of breeching (four to six). Breeching was when a small boy wore dresses before wearing breeches or trousers and was considered more of a rite of passage, rather than an eventuality.

As children grew, there was a solid business for the creation of mourning costume, as the children outgrew what they wore. Even from the 17th century, a mourning gown could cost upwards of £5, which is an incredible sum for the child in mourning. Dying dresses was acceptable, particularly during the 19th century, making an affordable way to denote mourning in society.

Mourning is often driven by the Crown, as in the 17th-19th centuries, the monarchy delivered the latest fashion to the public. Queen Victoria established the ‘Christian family’ and standardised much of what was expected from social propriety (from weddings to Christmas), hence her entrance into perpetual mourning in 1861 following the death of Albert enforced much of the understanding we have of mourning today. Victoria wrote to her eldest daughter ‘Vicky’, who married the Crown Prince of Prussia, and reprimanded her for not putting her 5-month old baby into mourning, stating that the baby should be put into ‘white and lilac, but not colours… I think it quite wrong that the nursery are not in mourning… You must promise me that if I should die your child or children, and those around you, should mourn; this really must be.’

Mourning regulation went through different permeations in the 19th century and became longer and more rigid. It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning: ‘the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crape hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crape fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crape hatbands and black swords and buckles.’ For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear. Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

For the stages of mourning, one of the most important factors is colour. For example, turquoise was often used as a during the half half morning stage, post Third Stage (or Ordinary stage) as a mourning material, with its influx of colour. This stage was introduced after twenty-one months, involving the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted. Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months.

The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life.

From the examples of growth through mourning fashion which was driven by entire families regardless of age, improvements in technology to meet demands for mourning costume developed. Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crepe gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act.

Their decline came in 1886, with the 1880-82 period of fabric being ordered at 46,000 packets of fabric to 30,000 in 1892-94. This is a steep decline that relates to the end of the mourning industry and its fashion. The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways. Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

Mourning for a Child

But what about the impact of a child’s death on the family? How was this worn or displayed. The Neoclassical period of the 1760-1820 period revealed a personal nature of mourning that had not been captured to its fullest extent in previous early-modern times. The depiction of a couple mourning their child, and the symbols to identify the child with, became clearly displayed in popular jewels and fashion. The unmarried and virginal of society were shown in white enamel and clear depictions of love and mortality, but this was a continuity. Larger events, such as the death of a young member of the monarchy had the potential to drive mass mourning throughout culture and this was clearly evident in the mourning of Princess Charlotte, who died during childbirth in 1817. This event had a multiple effect to British society, as Charlotte was 21 years old and died during childbirth, elevating the concept of the death of the young and enforcing Court mandates around the stages of mourning that would resonate through the 19th century.

Queen of the United Kingdom. Her father, George IV, had a contentious relationship with her as she grew older, with pressure to marry William, Hereditary Prince of Orange, a courtship that she ended. Eventually, she married Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a relationship that lasted one and a half years.

Charlotte’s mother, Caroline of Brunswick, had restricted access to her after her birth, allowed only by the accompaniment of a nurse and governess. In 1794, Caroline and the Prince of Wales were engaged, but hadn’t met, George had pursued this marriage due to debt. Her critics, with their leaning towards the throne, were not kind to her appearance or behaviour, however she was equally critical of George, stating that George was ‘very fat and he’s nothing like as handsome as his portrait.’ She was also critical of his excesses. George’s true love, Maria Fitzherbert, can be read about in the following article about miniature eye portraits:

Charlotte’s upbringing was praised by King George III who considered that her birth would bring Caroline and George back together, but the Prince of Wales was not so thrilled by the prospect of a daughter, rather than a son. George left a will stating that Caroline have no role in Charlotte’s upbringing and left her only one shilling.

Charlotte was christened Charlotte Augusta on the 11th of February, 1796, and became popular in the public’s eye. Breaking restrictions, her mother, Caroline, would be allowed by Charlotte’s careers to visit and even ride through London in a carriage, seen by the populace. Conflict between the Prince and Caroline continued through Charlotte’s childhood, however she remained close to George III. Upon George III’s affliction of ‘madness’, her father was sworn in before the Privy Council as the Prince Regent on February 6th, 1811. Political views, surrounding the Whigs, caused conflict in their relationship, placing restrictions from George upon her; both monetarily and socially. By 1813, George tired to enforce the wedding between Charlotte and William, the Hereditary Prince of Orange, a wedding frowned upon by the Princess of Wales and the public. George tired to involve her with even heavier restrictions, calling her to Cranbourne Lodge without being permitted to be seen by another other than the Queen, driving Charlotte to her mother and supporters. She was advised to follow her father’s orders and remained at Cranbourne Lodge until movement to Weymouth. By 1815, she had turned her affections to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg. Following her father’s approval, an announcement was made in the 14th of March, 1816 to the House of Commons about their impending marriage. The two were married on the 2nd of May, 1816, to the great acclaim of the populace of London at 9pm.

Suffering a miscarriage in 1816, Charlotte remained in the social spotlight, yet under watch by the physician-in-ordinary, with another pregnancy announced in April 1817. On the 5th of November, 1817, Charlotte gave birth to a stillborn child and died soon after.

The death of Queen Charlotte was one of high cultural impact upon the United Kingdom, following on from her popular perception in the public eye. This cascading effect led to the production of memorial tokens of affection that were created to symbolise her loss.

In the same way that the culture created tokens for Horatio Nelson, Wellington and Napoleon, this was a society that had the means to create popular souvenir tokens for the event, the craftspeople to deliver them in high demand and increased production through discoveries in the Industrial Revolution.

However, regardless of the affectation, this was still a society in shock, Charlotte’s death fed an industry that demanded the tokens of mourning to show their love and appreciation for her and her child.

One of the most important reactions to Charlotte’s death, from a mourning perspective, were to the stage of mourning and the requirement of fashion. These requirements resonated throughout the 19th century and led to the height of the mourning industry. This was a culture with a high mortality rate and a culture that looked to the crown for the requirements of proprietary surrounding love and death. A culture that needed to follow the context of ordained indoctrination in the affectations of fashion which established the stages of mourning. Everything from tea services, prints, poems and tea services were created for Charlotte, even with a petition to St George’s Chapel erecting a large marble structure for her. This ranged from levels of society, with Lord Holland noted that there were “signs of mourning on their persons” to the postboys and turnpike men that he passed.

It is indeed important that Charlotte’s passing affected the concept of mourning throughout Victoria’s reign. It took the identity of an entire culture and led it towards a new standardisation of fashion that led to a requirement of mourning and enhanced an industry that utilised mourning as a source of income. Through being the death of a child, the impact resonates even stronger than just the timely passing of a monarch; this Princess and future heir to the throne died. If ever there was a connection to what ‘memorial’ jewellery stands for, this is it. It connects a society and is worn and displayed as such.

White Enamel & Jewellery Dedicated to Children

White enamel is the second most popular mourning material used, next to black enamel. Black enamel, being a colour that has represented death through to pre-history, was (and still is), the colour that was inlaid in jewels, most commonly with the ‘IN MEMORY OF’ sentiment. This was highly standardised by the 19th century, but in the 18th, there was much more flexibility with the use of sentiment and enamel colour.

Death, for its reasons of desecration and entrance into entropy, lead towards black, which in itself, is the absence of light. White, when in use, is the connection to purity, innocence and virginity, show the untarnished representation in colour towards a person’s morals and values. A young person who was not married was seen as unblemished in social status and the use of the white enamel to show this virtue is why white enamel is used in this context.

Colour and symbolism became the primary elements of the mid-18th century, with the introduction of the Rococo period and its infusion of naturalistic designs in jewellery. The previous Baroque period was notorious for its bolder, dominating design, however mourning jewels represent something far more personal than what could be reflected in grander statements of building and architecture.

Cost and the essential nature of wearing a mourning jewel requires that the wearer invest some intrinsic personal affectation into the jewel and that the jewel must reflect something of its time. The 18th century essentially established the industry of mourning, due in part to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of faster methods of production and a society which was becoming more and more mobile, with greater access to education and techniques.

In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

Not only did the inlay of enamel become a process which was being influenced by the influx of skills from the continent, but the styles that the Protestants introduced into England allowed for a cross-cultural sharing of new ideas. White enamel as a virtuous display of young life was becoming a mainstream consideration, which the above ring from 1699 shows.

After this influx of Huguenot talent, the mourning industry grew along with jewellery development. Mourning rings were flourishing under a stabilised government that had not been seen under the Interregnum (Cromwell) period, as well as the new wealth that was developing from the burgeoning Industrialisation movement. Comparing this ring from 1730 to the 1699 piece, there is a large degree of standardisation in the design elements. This is a ring produced after the various elements of mourning in jewellery had become common enough to interpret without being seen as a jewel for aesthetic purposes. This is clearly a ring made for the purpose of grief in the style of its time. Gone are the memento mori elements (though these were still fashionable, however they had become smaller in size) and introduced is the name and dedication of the ring written around the band.

This ring contains the last moments of the Baroque period, with the straight edged band and not the nature-inspired, Rococo elements that would dominate the following thirty years.

Here, the Rococo design elements have become the mainstream fashion in jewellery and the influence on mourning jewels shows. In the ribbon/scroll/twist motif, the ring is highly fashionable and utilises the memento mori skull underneath the crystal, which is almost a statement against its fashion. This is a ring made for death and grief, so any association with being part of the fashionable Rococo movement is not an attractive prospect.

As seen in the 1730 ring, all are standardising the sentimental dedication in the band, yet just adapting to whatever style was popular. With the message of the ring being so strong as to dominate the sentimental nature of the jewel, introducing a new style at the time would be contrary to what mourning regulation required. Mourning, at this time, was Court mandated and hence was a necessity within society to present oneself. Particularly when a young child or unmarried woman in a family has died, not utilising the white colour of the enamel would be considered inappropriate and a message to the values of the family.

For the purposes of creating a ring, unlike these bespoke rings with an individual dedication written into the bands, white enamel rings with ‘In Memory Of’ which have the written dedication inside the band, were not as common until the turn of the 19th century, when a century of building mourning style into the lexicon of mainstream society had cemented it as the requirement of a family. As it had become common, then a jeweller could pre-make several rings and have them ready for when wills required rings to be given out at a funeral.

This 1777 ring is the perfection of children’s mourning during the Neoclassical period. It is captured with the depiction of the urn and weeping willow being superbly detailed. Still with its crisp, sepia hues and exceptional focus on detail by the artist (note the source of the light from the left and the capturing of shadow to the right), the ring balances the style of the time with the white enamel band. The oval shape is an identifier of popular style from the 1770s to 1780s, with the larger, navette shape taking prominence throughout the 1790s. Much of this was due to the popularity of the Neoclassical symbols themselves. As these grew popular, so did the need to have a larger canvas to display more in a ring, pendant or bracelet clasp.

Past the Neoclassical period, the streamlined geometric styles that were popular in the Regency era had shown a cleaner design to the band, with the focus on font and a singular element being the most prominent element to the jewel itself.

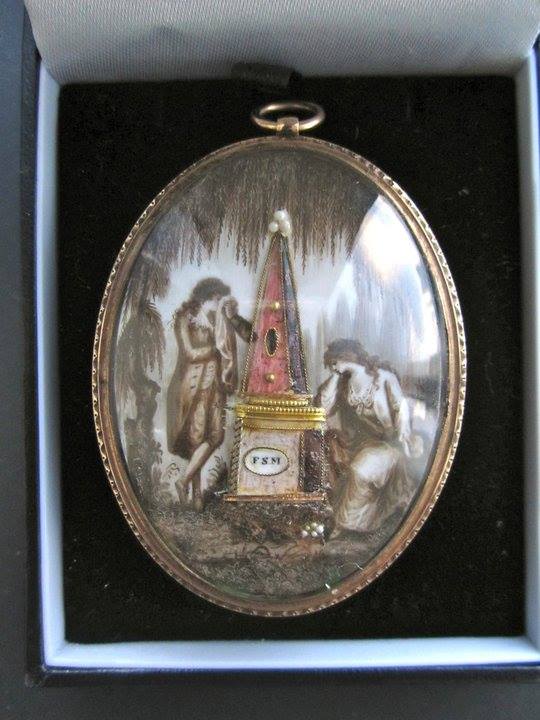

Clearly, children in mourning jewels during the Neoclassical period were worn as prominent symbols by their parents. White enamel was the key to understanding what it was for a parent to be in mourning and this remained through the 19th century, but not shown as prominently. Death, as entropy, had taken the colour of black in the 19th century, as it had in the pre-1760 period. This is why looking to the Neoclassical period is so interesting to see parental grief, as the ‘self’ was depicted in art. Of note is his perfect 1787 pendant:

This is the perfect depiction of the family’s grief. Both parents are shown weeping next to the tomb, identified personally without any other representation, right down to their costume. This is the perfect image of a real scenario captured within a jewel and the child is the subject at only eleven years old.

During the 19th century, black would prevail and it’s perfectly captured in this brooch which has the dedication of ‘IN MEMORY OF MY DEAR CHILD’:

From what can be seen in the costumes of children and their involvement within a funeral, to the use of jewels and how they defined everything from the immediate family to an entire culture, children and death are driving forces of mourning fashion. Our existence is built upon memory and growth, so without a child to carry this forward, it immediately invalidates our own identity, hence the jewels that are produced for family/parent mourning are so important to what they identified with.