Berlin Ironwork Jewellery

Giving something precious for an important cause is considered one of the most respectful ways to show honour and fidelity towards a Crown or government. It shows solidarity and unity within a community, regardless of its age. Jewellery is a privilege for the wealthy, with various metals and symbols being elements of identity within a society, this is why the phenomenon of Berlin ironwork is so important for the solidarity of Prussia and for the status of the wearer.

Berlin iron was founded in the Gleiwitz Foundry in Silesia, a mineral rich area within the borders of Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic in the c.1790s. It was further produced and developed in two areas. Count Stolberg’s Foundry and taken up by the Royal Berlin Iron Foundry (c.1804) both developed the technique, firstly carving/moulding shapes in wax, pressing these into fine sand and filling the impressions with molten iron. These pieces were left alone to cool down, then finished by hand and black lacquer was applied. Niello work was a common decoration, with ‘fine silver wire set into engraved lines in the iron.’ Examples have also been produced that are set with gold or medallions (notably Jasper) and cameo portraits.

French production is suggested to have begun c.1806, when Napoleon marched on Berlin and took the casting moulds, but why was the act of giving gold for iron so important to Prussia? During the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia had exhausted much of its revenue in the war effort. As the Prussian War of Liberation (1812-14) commenced, men offered their services and women offered their jewels to the Royal Treasury in an act of patriotism. Ladies that did received iron jewels with the motto “Ich gab geld um Eisen” (“I gave gold for iron).

Stylistically, the iron jewels imitated many of the popular and classical styles of the time. Scrollwork, classical medallions, cameos, and foliage were typical and popular. Neoclassical design has much influence on Berlin ironwork, as these were the popular styles of the late 18th and early 19th century, but the ironwork adapted to the upcoming Gothic Revival styles, which suited the stark, dominant style of the iron itself. As time drew on, ironwork had spread to Paris, Bohemia and Austria, though it had become far less popular than it had been. Demand peaked in the 1830s, when Berlin alone had 27 foundries and manufacture spread to France and Austria. Ironwork jewellery was also displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and continued into the 20th century through the same act of giving gold for iron in the war effort. More will be written about this later in the article.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel, the designer of this piece, had an enormous influence on the success of cast-iron jewellery in Prussia. This iron cross was meant to evoke the insignia of a medieval German order. It could be awarded to anyone who distinguished themselves in battle, regardless of social status. This was a revolutionary approach to the award of honours and was consistent with the hope for a more egalitarian regime under Frederick William III (1770–1840).

The great designers of Berlin ironwork are Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who introduced the Gothic Revival style to Berlin iron and worked in the Berlin foundries, with other signed pieces being by Lehmann, Hossauer, Devaranne and Geiss. Identity of iron jewellery towards the Gothic Revival style cannot be understated. This jewellery lends itself to the intricate, large and dominant style of the Gothic Revival, which mourning jewels particularly adapted. Berlin iron was also worn for the purposes of mourning, but not exclusively. Notably, Queen Luisa of Prussia’s death was commemorated by iron crosses.

Gothic Revival, The 19th Century

The Gothic Revival is important to Berlin Ironwork through how well it adapted to this changing style. In the same way that jet worked so well for the latter 19th century and fashion (regardless of mourning), Berlin iron captured the style of the Gothic Revival. These pieces were large, intricate and emulated the high-relief Gothic motifs that resonated the Medieval style.

The Gothic Revival period of the early 19th century is an extremely pronounced period of obvious consequences in art and architecture, but also heavily affecting in morality and cultural lifestyle. It is a period that overlapped other forms of mainstream style to eventually become the dominant visual presence, particularly in memorial jewellery and had left its mark for the greater part of the 19th century.

Firstly, we must look at this emerging style to conflict directly with the ideals of the Neoclassical period. Though the Neo-Gothic movement had begun c.1740, it took around sixty years for it to reach mainstream thought, a time when Neoclassicism was at its height.

Much of this thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

It is important to note the diversity amongst European countries. From religious differences, to manufacture and the separation due to lack of communication or region, one concept such as the Gothic Revival style was not something that could immediate be adapted at once. Designers in Berlin ironwork, such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who was working within the Berlin foundries adapted this style and introduced it heavily into the ironwork designs.

Much of the latter 19th century jewellery designs had their origin in this Gothic Revival period, the bold mourning styles with black enamel as well as being larger accommodated the evolution of female fashion, which heavier crinolines and cuffs, seemed to be a perfect fit. Styles didn’t automatically become larger due to the Gothic Revival influence, much of the older styles adapted Rococo acanthus designs and incorporated Gothic fonts into the lettering of the dedication in the pieces, which emerged around the c.1800-1810. By the 1820s this style was influencing brooches, rings, pendants and lockets more and more, until the 1830s when it reached its height, particularly in terms of diversity. Through the 1840s it had become the standard and into the 1850s, there was the Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys. Reflecting this upon the larger styles of female dress, pieces could be larger and lighter to wear, yet still give all the bold, gold and black enamel prominence of the pieces themselves.

20th Century

War chests are not a modern invention, but one driven by expansion and cultural solidarity. Be they created for the purposes of being offensive or defensive, they have the power to gather a community together under the ideas of preservation and protection. Through the use of propaganda and clever marketing, governments can focus their attention on manipulating donations from a public. Fear is an important factor in any time of war; times where gathering fidelity from a public is mandatory.

In the above example, this ring is a primary source for its time. Much the same as the pieces from the Prussian War of Liberation, the message written on the ring is a statement of the individual in the First World War of their sacrifice for the effort. In the same manner as pins or posters stating that an individual or a community has given to the war effort, this ring shows its decoration in the eagle crest next to the statement of giving gold for iron. Other examples from the time have statements such as “Gold gab ich zur Wehr, Eisen nahm ich zur Ehr” (“I give gold towards our defence effort and I take iron for honour”), which carry the same sentiment, but enhance the personal message of honour within the jewel.

History and human behaviour don’t necessarily change, just the way people adapt to situations and technologies. As can be seen in this 20th century example, there’s exactly the same sentiment in the jewel as there had been one hundred years before. This was a development, however, that still remained popular in the consciousness of popular thought; visible enough to resurrect for a new generation, regardless of how successful it was. Be it for the coiffeurs of a government to spend towards a war effort or simply for scrap metal used in the war machine itself, extracting the precious metals from people who gave for their cause, the method is ancient, but in an iron jewel is modern. To understand this development, a look to the destabilisation of the late 18th and early 19th century is important, along with the popular styles which needed to adapt to an Europe facing less ready wealth.

Cultural Impact of Napoleon & Contemporary Styles

Napoleon’s impact across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries cannot be understated. From the instigation of war and conquer, to his adaption of classical style, it is through his influence that led to the changing styles of Neoclassical to Gothic Revival. Through the very nature of his invading Berlin and taking the iron moulds, Berlin ironwork has its propagation through France due to him, as well as the giving of gold for the war effort as well.

Early Berlin ironwork was Neo-classical in style, using motifs such as acanthus leaves, palmettes and cameos. James Tassie’s glass pastes and Josiah Wedgwood’s jasperware were copied for portraits and mythological scenes. The jewellery quickly gained an international profile. Demand peaked in the 1830s, when Berlin alone had 27 foundries and manufacture spread to France and Austria.

In 1789, the French Revolution affected jewellery wearing and production to a great extent. The First French Empire under Napoleon retained and grew the popular Neoclassical styled jewels, maintaining their position as the primary leaders of fashion. Even with the hostilities between 1793-1815, the English closely followed Parisian styles.

By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles may be enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security if fleeing the country.

Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

In 1797, the Paris Company of Goldsmiths was reinstated, after being abolished in 1791, reintroducing many of the goldsmiths from the reign of Louis XVI. By 1798, hallmarking was established in France, making it compulsory to stamp jewels under three standards of purity; 750, 840 and 920 parts per 1000. They were also stamped with a maker’s mark (the maker’s or sponsor’s initial) and symbol in a lozenge-shaped stamp.

Filigree jewellery and fine detail to gold work had its inception here, as there was as shortage of money and goldsmiths became inspired by French peasant jewellery to produce finely detailed gold with lesser materials. Seed pearls, basic gems (such as agates) were also popular, as can be seen in the following pieces:

In the above, we can see how the fashion of fine gold and the access to seed pearls from the Orient made for highly detailed and inexpensive jewellery. Large enough to be seen and influenced by the Neoclassical style, this was a society adapting to the hardships that they were surrounded by.

This ring is the product of the use and popularity of the carnelian in jewellery. As these elements become popular, they resonate throughout society and here we see it with the intaglio inscription of ‘pietas’ in a swivel ring.

In 1804, the Napoleon’s Empire was announced and luxury trades were renewed with vigour. Bijoutiers, who worked in ordinary materials and joailliers, who worked in precious stones benefitted from this rise in luxury, with Napoleon requesting the jewels from the former kings of France to be set in the Neoclassical style, essentially connecting him to the Greco-Roman empires. His coronation crown was decorated with cameos and his passions for the antique world led him to establish a school of gem engraving in 1805. If ever there was a height for the Neoclassical period, it was this connection to it. How other societies would reflect this moment is seen in their contention or support of Napoleon. Here is a person who is appropriating the classical world in a time where it had been in mainstream thought and fashion for around forty years. International tension would only lead to the decline of this style, as cultures needed to obtain their own identities in jewellery fashion. A great push to the Gothic Revival style in England has its roots in this.

Simple designs and smaller jewels following in this early 19th century period. The geometric shapes, ovals, circles and rectangles became popular, with the Greek key pattern utilised often in jewels. It was about balance, with many patterns being taken directly from Greco-Roman architecture and detail. During this time, until his remarriage, Josephine was the bastion of style, maintaining the fashion which people would covet.

From this, what we see is that society had to adapt to the shock of the Terror and the new Empire, all the while other cultures are looking to France for its style and reestablishment. Greater and more literal influences of antique cultures led to the allegory of the sentimental depictions becoming literal interpretations of their architecture in jewels, making the individual the monument to classical art itself.

Within the 1790s, the ‘language of stones’ had its emerged, using the first letters of each gem to become the acrostic dedication of the jewel. The “Souvenir” jewels consistently reference “friendship” and this is a concept built from the nature of the relationship around piety and faith. As a concept itself, this is the very fundamental nature of a relationship, but in jewels, it can be seen written in posie rings from the 15th century onwards. ‘REGARD’, ‘DEAREST’ and ‘LOVE’ are the most English of the love token jewels from the 19th century to develop. This is due to the fascination and accessibility of precious stones, which allowed for the growing classes that had greater access to wealth the allowance to purchase jewels that would only have been accessible for the high aristocracy and Court.

REGARD: (R)uby, (E)merald, (G)arnet, (A)mythest, (R)uby, (D)iamond

LOVE: (L)apis-lazui, (O)pal, (V)ermeil (hessonite garnet) (hessonite garnet) and (E)merald

DEAREST: (D)iamond, (E)merald, (A)methyst, (R)uby, (E)merald, (S)apphire, (T)opaz

Other messages written in stones were not uncommon as the style became popular. Napoleon’s second wife Marie-Louise commissioned three bracelets made, dedicated with her and Napoleon’s dates of birth, dates of meeting and dates of marriage.

It cannot be understated how important the French influence upon sentimental jewels was in the turn of the 19th century. From the souvenir jewels stating such terms as “Souvenir d’amitié” and “Souvenir d’armour”, the statements of love that were worn on display created a new social proprietary that involved the use of sentimental jewels to offer admired people, within social circles, as signs of courtship and love.

Much of this sentiment stemmed from the French Revolution and its cultural challenge to established monarchy and religious value systems, particularly in the form of Liberté, égalité, fraternité (liberty, equality and fraternity). While the French Restoration of the first-quarter 19th century had repaired the monarchy itself, the challenge to established order had accomplished a lot to put new values in relationships and empower individuals. George IV encouraged society to look externally for artistic influence, since his ascendancy (and Regency, post Regency Act of 1811), George’s investment in the arts was required for the aristocracy to have these tokens of love as social requirements above simple affectations.

The Bourbons were restored in 1814, with jewels being more sedate in their designs due to the lack of wealth. Threaded seed pearl on horse hair created ornate bracelets and necklaces, with materials being smaller and more abundant to exaggerate their use. During the 1820s and 1830s, the use of cannetille (surface covered with wire) or grainti (small granules) embellished the colour of gemstones, as the gold was used in the base of the jewel. As seen with the portrait of Lady Peel by Sir Thomas Lawrence above, the wearing of several bracelets and enamelled rings on one finger elaborately exaggerated the colour of the jewellery. Classical style was starting to become overcome with elements of the Baroque and Rococo, which had only been popular previous to the Neoclassical period.

How this affected the mind of the early 19th century individual was a direct stylistic move away from what had bought about the unrest of the Neoclassical style. With competing styles being mixed for mainstream appeal, the classical style in its literal form would recede until the mid 19th century and the archaeological discoveries that would ignite it once more, such as Etruscan.

In the early 19th century, there was much to define the self through the identity of jewels. Neoclassical allegory had put the focus back upon the elements of the natural world which could contain their own symbolism. In the above image, the REGARD jewel is seen within the coiled serpent, denoting eternal love and piety. Given as a keepsake for a betrothed, all of the above jewels have a sentimental resonance, denoting futurity and an offering of new life and love.

Jewels of the time are often repurposed or added to, creating a marriage of styles that need to be considered for their elements. The above serpent may have had a REGARD sentiment in its centre, just as the dove, serpent and crescent selection of jewels, but as their sentiment still remains a popular one to this day, many jewels are given from generation to generation. There isn’t a clear statement of love in these pieces, but there is the simple nature of the decoration in their design and the underlying sentiment of their love. Unless one understands the acrostic sentiment of the piece, then it simply is just a beautiful jewel to be given to a loved one.

While the sentiment of the jewel is written in the message of REGARD, the style is important to note. REGARD jewels aren’t relegated to simple rings or the round shape of this article. Rectangular shapes, such as this piece from the British Museum, have all the elements of the Baroque coming back into style, while adapting to the smaller shapes of the classical style. Note the acanthus surrounding in the border design, alone with how the gemstones are set to the brooch.

Shape is the most obvious thing to identify a jewel of the early 19th century by. The navette shape, being large in the north-to-south, had to accommodate large Neoclassical depictions of love and death, while these jewels, through their simplicity and design, reflected the classical architectural shapes and became smaller. Miniatures remained to be popular, however, with many miniaturists creating pendants and keepsakes (which were held within compacts/cases) bespoke or tailored to a loved one through a Neoclassical ideal of what the face should be.

The early 19th century was about colour and classicism. These jewels had their own language and ‘magical properties’ that were tailored to the wearer through their birthstones or the very nature of being colourful. Paste, or coloured foil and glass, was more popular and affordable than the gems themselves. Many of the pieces that were created for REGARD jewellery in the Georgian period were often paste, yet still retain the message of love that the jewel was created for.

With the above images, the REGARD gemstones are set within a basket of flours, as well as rubies and turquoises. This is a testament to how popular the REGARD jewel was later in the 19th century, as this is a charm created with a compartment containing a photograph. Essentially, if the piece was not created simply for the containing of a photograph, it was repurposed by another generation to use the space for hair in a photograph.

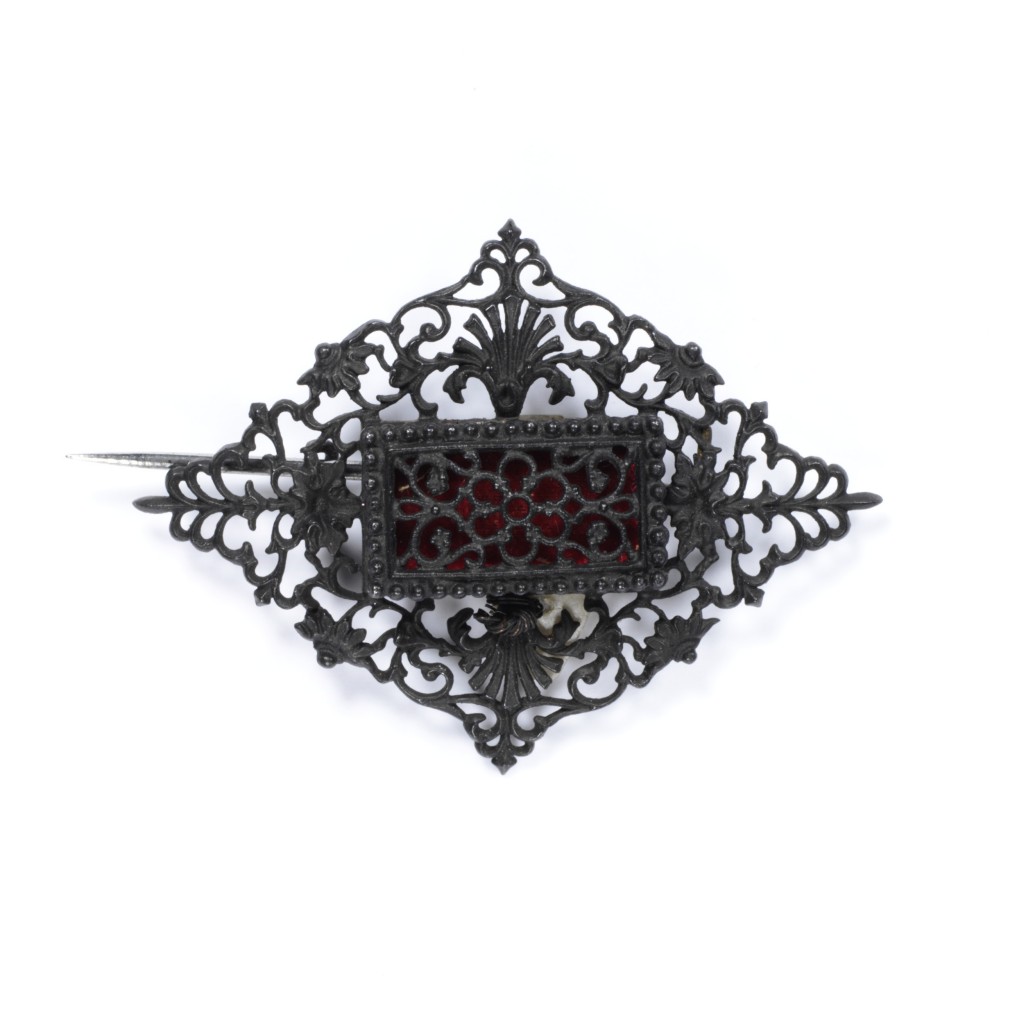

Berlin ironwork designs are important to note for their contemporary designs. There was much variation in the refinement of the Neoclassical style that much of its grandeur was giving way to the Gothic Revival style simply based on the opulence in the new style’s detail. The fine oval shapes, smaller brooches and refined gems in heart and symbolic motifs were being overcome with the Gothic Revival’s lattice, acanthus and architectural shapes, which, when worn on the body, are quite striking as a fashionable item. Note the above brooch from the 1820s and compare that with the REGARD pieces and how their dainty symbolism is intricate in style, but very small in stature. As stated, much of this was due to the decline in accessibility of gold and materials during and after the Napoleonic Wars, hence the use of iron led to larger designs that weren’t as expensive.

Forged

Unfortunately for iron jewels and accessories, they have deteriorated over the years. Iron’s susceptibility to rust and the delicate construction of these jewels has made them disappear over the years, but many remain in museums and private collections as a wonderful keepsake to this cultural phenomenon. What cannot be removed from the jewels, however, is the culture and identity of the people who wore them. These people believed in a greater ideal that they identified with and united with their community for solidarity and protection. A sentimental token of love that may have been given to a lady was donated for a jewel that prominently stated fidelity to the government or crown, which is a large sacrifice to make. When a jewel is a trigger for a memory, it’s a personal affectation. Here, identity is given for the sake of a whole and that is one of the most remarkable factors about iron jewels.