A Relic of George III in a Mourning Ring

Mourning jewellery of the 19th century scales between the most common jewels that were worth shillings for the pauper, to those created for kings and queens. Both variants of mourning jewellery design have relevant reasons as to why their designs captured the imagination of a wearer, who demanded that their loved one’s memory was encapsulated within.

For royalty, mourning jewels that were produced offer an insight into the styles of jewellery that much of the public would find aspirational. These jewels were public knowledge, as their creation and being worn was reported through gazettes and fashion publications. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, an increasingly affluent, educated, upper/middle class society would speak about the popular fashions of the day in parlours and salons. With this scrutiny, the British royal family’s fashion and lifestyle was seen under the lens of the public eye.

By the early 19th century, the younger aristocracy had grown alongside the behaviours of the Prince of Wales. Wealthy, educated men would live off of their inheritance, often above a yearly income of £10,000, to travel, gamble and live voracious lifestyles that previous generations had not seen. Commercialism, fashion and social behaviour hit a nexus of status that pushed the wealthy to regularly change, update and influence their styles with what was current or progressive in fashion design.

Mourning jewellery offers a great deal of insight into these behaviours, as death was an absolute and the expectation of offering a mourning jewel at a funeral was built into upper class expectation since the 17th century. Testators would assign a budget for mourning rings to be produced in wills from this time, notably the Earl of Oxford, Robert Walpole, whose death in 1700 left behind 72 rings at the value of £1.00 each. This was a great sum of money in a society, where the average yearly income for a wealthy man was £400-£500.

George III’s reign (1760 – 1820) existed during a time when global markets were driven by aggressive mercantilism and the strength of an empire was bolstered by its imports and exports. Having communities that existed across the globe made fashion identity important for offering a universal standard of behaviour for that empire. British values were engrained in Neoclassicism; the Enlightenment’s visual representation of bringing back the Greco/Roman cultural values and modernising them in the 18th century. Having these values of Humanism based on René Descartes’ ‘I think, therefore I am’ value and John Locke’s Liberal philosophy, which adhered to the rights of life, liberty and property, gave society a reason to value itself as important, rather than living under an ecclesiastical and agrarian society. This antiquated society offered no social progression and no option for fashion to be a part of daily life underneath the highest classes. Fashion in the early 19th century was influenced by those raised under the values of Locke and Descartes, which was now considered social progression. Death in jewellery was the ultimate representation of this, as the value and design of the jewels of mourning would encapsulate the entire value of a family.

‘A Relic of George III’ is the inscription in this ring, along with the coronet of George III, making this ring an invaluable insight into the lifestyle, religious value and social behaviours of the early 19th century. George III died in 1820, with his health declining in the final decade of his life, where in 1811 he acknowledged the need for the Regency Act, which allowed for his son to act as Prince Regent. Death’s influence in the decline of George III’s mental health was related to his youngest daughter, Amelia, who passed on in November 1810, leading to his dementia. The effect of George III’s health on the public during a time of increased circulation of newspapers and gazettes was prodigious. George’s health was the subject of public sympathy and during a time of the Napoleonic Wars, his symbolic power as a figurehead was essential to maintain stability and strength within the British Empire.

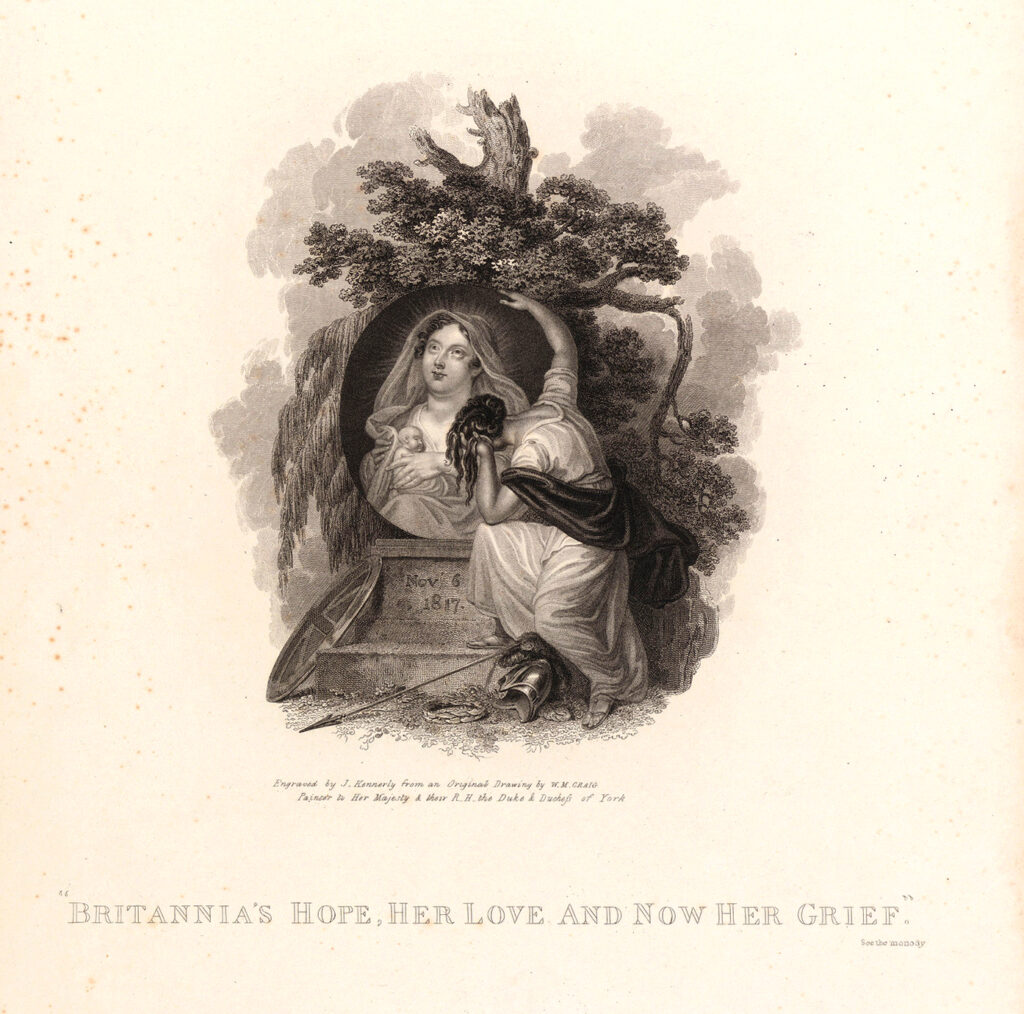

Following his decline, his granddaughter, Charlotte Augusta, died in November 1817 and his wife, Charlotte in November 1818 creating an even larger outpouring of public mourning. Charlotte Augusta was seen as the sympathetic heir to the British Empire from her father, the lesser respected George IV, and her potential reign was related to that of Elizabeth I. The Princess of Wales would be the hope of the British Empire.

Mourning jewels at this time followed a precarious need for conformity in design. A jewel being designed to encapsulate piety and fidelity from the public walked a careful line of being fashionable and also highly respectful, while still offering an insight into what jewellery design would consider progressive. The mourning ring for George III shows this in abundance, with is concentration of modern design, showing a growing shift away from Neoclassicism and more towards the Gothic Revival style.

The Gothic Revival was a move away from the excesses that the late 18th century lifestyle had produced, leaning towards a value system of Medieval piety that was missing from an increasingly urbanised England. Architects, such as Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852), were inspired to design against the styles that had created large, brick, urbanised housing and this began with an edict upon building churches in England. The ‘Million Pound Act’ or Church Building Act, was a series of Acts between 1818 and 1824, granting money for the Church Building Commission to reinvigorate the Church of England, bringing ceremony back to the church.

Catholic ecclesiastical jewellery had been banned in England since the middle of the 16th century by Henry VIII, making mourning jewellery a style that comes close to the values and ethics of religious jewellery. A society that had been raised viewing the effects of what Libertarian idealism could create, which was essentially the fallout from the French Revolution, required society to use designs that had more values of respect and conservatism. The Gothic Revival style was a perfect conduit for jewellery to show the values of respect in society, especially when used as a way to denote the passing of the most important figure within society.

George III’s death on the 29th of January, 1820, led to an outpouring of grief and integrated his image in classical styles, creating strength and legitimacy through his image.

Mourning jewels during the end of George III’s life reflected the values of society and politics. This was a shift away from the designs of Neoclassicism, which encapsulated allegorical symbolism, in the same way that the ‘Celestial Meeting of the Royal Family’ engraving showcases classicism and Romanticism.

Romanticism brings back Medieval chivalry and sets the foundation of how behaviour should be in a pious marriage. The Gothic Revival style plays upon this, much in the same way as an illuminated text, to present a jewel showing the written word of mourning (often ‘IN MEMORY OF’), with a Germanic, Gothic font.

Design embellishments in these Gothic Revival jewels of the early 19th century feature the gold designs of roses and acanthus, which are interpreted from classical designs (notably seen in Corinthian columns), then appropriated again for Baroque design in the 17th century. These designs were made popular once more, as their ties back to the classical movement offered the majesty and piety that the Church of England was looking to bring back into its services. As a system of control, mourning rings were a prime example of fashion for popular culture to adhere to, for their necessity in gifting and wearing were a message to the greater populace about what were important in social values.

George III’s mourning ring shows these values in the style of its shoulders. It utilises the bold rose and acanthus design pattern, while creating an elaborate housing for the woven hair and garnet bezel. It directs the message upwards, showing piety for the king and preventing any dilution of what its message should be. This is a ring that shows love for the subject, as many jewels of the early 19th century did.

Having a mourning jewel in the early 19th century, featuring woven hair under glass atop the bezel, was the most common form of mourning sentiment. This style would remain until the woven hair compartment disappeared beneath the bezel during the c.1850s. In the example pin seen above, the garter symbolism coils around a simple twist of white hair. It is designed with Gothic lettering and the rose/acanthus embellishments. Simplicity in bold design was cheaper to produce than the earlier Neoclassical pieces, which contained more expensive materials, such as ivory, or when there was a requirement for a miniaturist to paint the jewel with a bespoke sentiment or image.

Developing this style from the 18th century into the 19th century was essential for the budget conscientious, as there was a large demand for mourning jewels to be produced in Britain. The Napoleonic Wars were depleting the British gold supply, yet the requirement for the jewels was rising. Piety through the use of hair was cheap and effective, as well as making the material far more precious in the eyes of the public.

It is interesting that royalty was reflecting the more common mourning jewels of the public during the 1820s, seen in George III’s ring. Princess Amelia’s death in 1810 was a statement to the public about her life and an order to recall her memory. This is the basis of the ‘IN MEMORY OF’ statement that would be such a previlant epitaph in mourning jewels, which also relates back to Christ at the Last Supper saying ‘do this in remembrance of me’ (1 Corinthians 11:24).

Amelia’s mourning rings, medals and mourning products were designed with the statement ‘REMEMBER ME’ and they were produced in high volume. The white enamel ring seen above from the Royal Collection Trust UK was produced in a batch of 50 from the royal jewellers, Rundell & Bridge. These rings cost 58 shillings each, which was quite affordable for their time and the person whom they were made for. Royal patronage of Rundell & Bridge lasted until 1843, spanning four monarchs. When Philip Rundell passed away in 1827, he left behind £800,000 and in 1799, was considered the 8th richest, non-royal person in Britain, owning more than £1,000,000.

Remembering Amelia was an important value for piety towards the crown and stability, as well as stating the importance of creating an item of status within society. Having a ring like this as the template for what the wealthy in society should be replicating required an affluent society that relied on constantly evolving fashion, which Britain did. Using this element of piety was an intelligent step in social conformity through products. Many of the items that were produced as memorials for Amelia moved away from the allegorical symbolism of Neoclassicism to use the stark reminder of memory and mortality.

George III’s mourning jewels continued the evolution away from Neoclassicism and back to Medieval values. His primary mourning ring, created by Stephen Warwick, was a culmination of royal deaths and their jewellery designs, leading to the perfect style for a popular monarch.

George III’s ring reads “HONI. SOIT. QUI. MAL. Y. PENSE” (shame on anyone who thinks this evil), the motto of the Order of the Garter, which was created by Edward III in 1348. This is the oldest order of chivalry in Europe. George III was the guiding star of the British Empire and his depictions showing the Order of the Garter star over his heart were common. George was the figurehead of strength and the Order’s symbols reflected his association with chivalry, in the same way knights would protect the sovereignty and social values.

Bringing the values of a chivalric order to the forefront of jewellery design in a mourning jewel speak of the pious values and rituals that were important in British society for their time. Having these values state that this is how the people should behave set the boundaries for courtship, marriage, families and death, which were a radical change from the Neoclassical designs that had come previously.

In jewels of the previous generation, the depictions of the people courting, the birds denoting their union and potential birthing of children, would all lead towards what was seen as the classical sentiment of relationships in design. The shift in having mourning and sentimental jewels using elements such as hair and gems as the primary elements of symbolism, then combining with a secondary symbol, amplify the personal message of direct love. In George’s garnet and hair ring, the secondary symbols are Baroque, leading into the values of the Gothic Revival.

Having George as a conduit for sentimentality was important for all of society. His mourning ring with its Order of the Garter was a message for society to behave with solid values. It was also amplified by its use of the colour blue, which was considered ‘Royal Blue’.

This was a colour that was used as a competition for British industry to discover a colour unique for royal use, specifically for Queen Charlotte. A factory called Scott’s Bridge in Rode was selected as the victor in this and George selected the colour of ‘The Royal Blue’. French Blue had been a colour used by the French monarchy since the 12th century and ‘Bleu de France’ was a colour widely known in the lexicon.

Much of the cultural building of values in mourning jewels of the late 18th and early 19th century were to build a solid value system for the British, which had only been unified as a United Kingdom since 1707. This was a relatively new union by the early 19th century, so its validation through symbolic values was essential to maintaining stability. Being a culture built upon solid financial grounds and isolated to its isles, the British could establish its cultural values through strong symbology that related to the sovereignty of its times.

Garnets had been popular in jewellery since ancient times, used by the Egyptians and Romans. In mourning jewels, it is important to note that in the 18th and 19th centuries, the garnet’s colour was the most important reason why it was being used. Colour theory was a popular movement during this time, with philosophers looking to scientifically assign colour to emotion.

Colour theory relates to mourning fashion, as each stage of mourning (First, Second, Ordinary and Half) all have different protocol to follow in order to show personal respect for the deceased. Women spent 1 year and 1 day in bombazine and crape for First Mourning, 9 months with less crape for Second Mourning, 3 months with black silk, ribbon and jet for Ordinary Mourning and 6 months in Half Mourning colours, ending the 2.5 years in mourning.

Garnets were acceptable during the Half Mourning phase, where heliotrope, mauve, purple, pansy and scabious shades of purple were allowed in fashion. Deep red was also passable for a lady who was attending the wedding of her children, during this phase. Mourning jewels were created at the time of death and even after, as memorials. Ladies of fashion could also plan ahead, given the budget dedication in the will, for a suite of mourning jewels.

Royal Blue was a similar colour used in late 18th and 19th century mourning jewellery, both have value for respect, with blue considering the loved one to be royalty and the red/purple hues of a garnet to show truth, constancy / fidelity in every engagement and virtue. Using this colour in George’s ring is a powerful statement of the wearer to offer their respect to the monarch as the figurehead of the kingdom, even after death.

This ring may be a relic of George III, but it is a powerful statement of its time, culture, class and religion, which was vastly changing during the 1820 – 1840 period. Even the most powerful of kings could be encapsulated in a humble ring with a pious design, in a style that was also attainable for production by the populace.

Gothic Revival design created an important shift for the British towards social conformity, which was essential in a time of high urbanisation and rapid mass media, which could disseminate a message through a newspaper or gazette to challenge the political establishment. Through social measures of behaviour, mourning jewellery creates sympathy and solidarity in fashion, offering security during times of potential unrest.