Death of Youth, A Life Cut Short

It has been said that living longer than your child is the worst fate of all. The concept of creating a life to continue your values and memories, or that of a family, is fundamental to the completion of one’s own existence. Grief and its interpretation throughout the early-modern period finds its gravity within the jewels and art that represent the death of a youth. These jewels tend to resonate a very personal grief, which gives the modern viewer an insight into how people dealt with grief.

Beyond the tokens of death that are created in high volumes for the deceased and given out at their funerals, loving tokens for children are often created suddenly; without the foresight to plan ahead for the death of the young. This is not always the case, as illness and other eventualities could be planned around, but the various symbols that reflected the grief of the parents is far more personal than just the standard elements of grief and love.

The Neoclassical period (c.1760-1820) used allegorical depictions to represent love and death. The female, who was the figure that represented human emotion, is often the figure of the mourning jewel’s focus. She may be weeping next to a tomb, pointing to the heavens or standing in Greco-Roman dress next to a mourning symbol, such as an urn. This is not the case with this ring for a deceased child.

“Nipt in the bud” is the sentiment written for Butterfield Harrison, who passed away on the 14th of March, 1792, aged 2 years, 9 months and 14 days. This ring is important for many reasons; from its immediacy in death and how that influenced its design, through to the the nature of the symbols.

Primarily, the roses are the central element to this ring. The statement of “Nipt is the bud” is quite a literal one, as the rose is cut and falling away from the others on the left side of the ring. The three roses are reaching towards the heavens, yet the one that has fallen away is directly pointing to the ground as it falls. Rose symbolism for the bud that has not yet bloomed is for a child who has passed on, generally younger than twelve years old.

For a child who had not seen his third birthday, the ring brings into question just how long the parent had to plan for the jewel’s creation. Was Butterfield suffering from an illness to plan the design of such a ring, or was this ring made to commemorate the event after the fact? Its design is unique. The roses and symbolism in this jewel speak of the parent’s personal understanding of the cut rose symbol, as it was created to signify the event and for them to recognise its meaning.

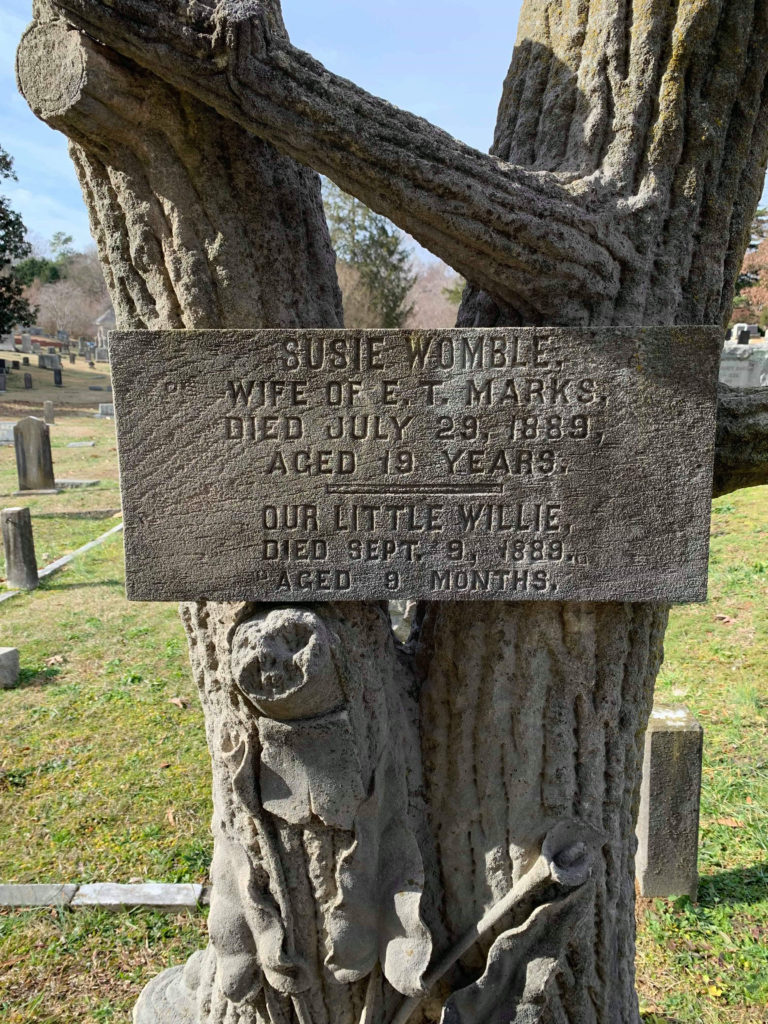

The symbolism of the life cut short and its representation in flora translates to funerary art. Graves, with the elements of a tree being cut, are just as prolific as a broken column or draped urn. A tree, which has its branches broken, can be seen in the following tombstone for Susie, aged nineteen years, and Willie Womble, aged nine months. Here, Susie is married, yet the combination of the nine month old child in the style of this tree is poignant:

Here, the symbolism is much the same as the ring. Youth, represented in the flowers, along with the trunk and remnants of the tree, have been cut short in life, just the same as the young wife and child.

Mourning jewellery’s translation from being a jewel into a wearable tombstone for the loved one takes on a new element with the death of a child. Jewels that were produced en-masse for friends and family resonate as a token of memory, but to tailor a jewel for a specific individual is where children’s mourning jewels become quite bespoke.

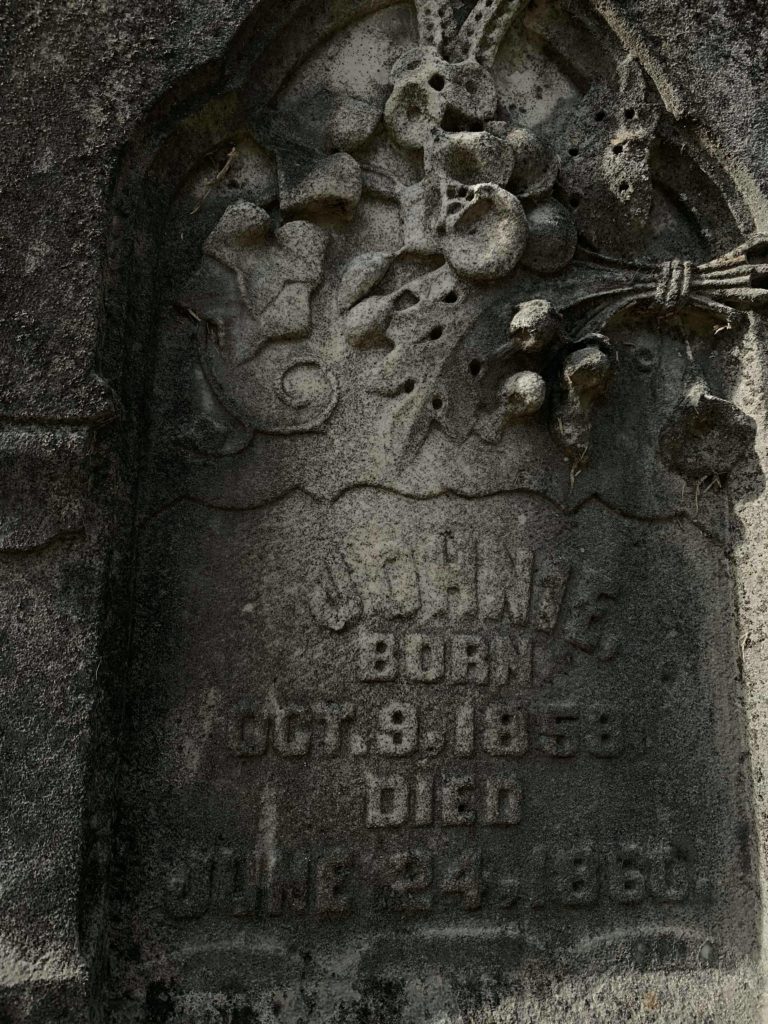

Wilted flowers representing the absence of life, the grape vine to honour the Christian faith and all of the funerary elements in this tombstone are reflected in jewels fo the late 18th and 19th centuries. These symbols became part of the Western understanding of death, which transposed itself across continents. A ring worn in England, such as Butterfield’s ring, would be identifiable in America, as these symbols are obvious and popular enough to be interpreted.

Beyond the tokens of death that are created in high volumes for the deceased and given out at their funerals, loving tokens for children are often created suddenly; without the foresight to plan ahead for the death of the young. This is not always the case, as illness and other eventualities could be planned around, but the various symbols that reflected the grief of the parents is far more personal than just the standard elements of grief and love.

An example of this can be seen in the following jewel. The female, an allegory for human emotion and the ideal, becomes the figure that is the vessel of grief and love.

When compared with the how mourning was represented by a parent, the result is quite different. The male in mourning is far more personal to the wearer. In Neoclassical jewellery design, the depiction is far more literal, being closer to how the male actually looked. Note in the below jewel the depiction of the mourning male, then have a look at the previous lady in mourning,

Note how the lady is wearing the classical costume, echoing the Greco-Roman style, with the bunched sleeves, under-bust cut, long folds and veil. Its Neoclassical style was a reflection of the popular taste of the time. There is the allusion to the general ideal of the female, which would be adapted for the wearer, who was in mourning, but it is also a general indication of the family’s grief and feeling.

The gentleman is wearing popular male costume of his time. The pantaloons, frock coat, hairstyle and waistcoat are far closer to the character’s daily costume, rather than that of the totem that the female is in the previous miniature. His scale and depiction in the scenario is unusual, however. The character is painted in the area that a female character would be, yet he is dominated by the large urn and weeping willow. If these elements were pre-designed and he was a later addition to a miniature painting, it would be possible, as the negative space was tailored by travelling miniaturists for rapid production and sale.

What all these jewels and funerary art speak to is how immediate grief manifests in design. Planning for the death of a loved one took time, particularly when production wasn’t rapid and design was highly detailed.

The immediacy of death, when a child is involved, makes the impact of the death far more visceral in mourning depictions. White enamel is one way of commemorating the death of a child, or unmarried, but when there is symbolism involved, the art is quite personal. Here, ‘Nipt in the bud’ is a beautiful sentiment, with the cut rose being the signifier for the death of the loved one. As seen with the male mourning ring, the person who commissioned this kind of jewel could put themselves in the jewel or allude to the death with a memento and the ‘Nipt in the bud’ ring has all the trappings of a ring that was elegantly designed for a personal sentiment.