Death at Sea: Mourning Jewellery and Nationalism

Being lost at sea strikes an image of loss and departure that evokes the very essence of sadness. In the very literal sense, there is the loss of the body that prevents the kind of closure that physical remains offer. Yet, in terms of symbolism, the loss of the soul is the same as that of the body, representing a crossing over to a place that we do not know or understand. It is not surprising that symbolism featuring the sea has been appropriated by mourning jewellery. The physical and symbolic departure of the soul away from the mourner as a result of a death at sea, during both peace and war times, are depicted in 18th and 19th century jewellery.

Public mourning led to memorial jewels being made to commemorate people and events. Wearing patriotic jewellery formulates identity for a culture, strengthening a singular thought, and reinforcing leadership regimes in the public mind.

Ideals around the mystery of the sea and the fear of the unknown drive a great deal of romantic thought about that which is unexplored. As a personal concept, a voyage into the unknown can be dangerous and exciting. However, the jewellery that depicts the ship, sea and/or mourning figure hinges upon representations of loneliness and longing for the departed to come back.

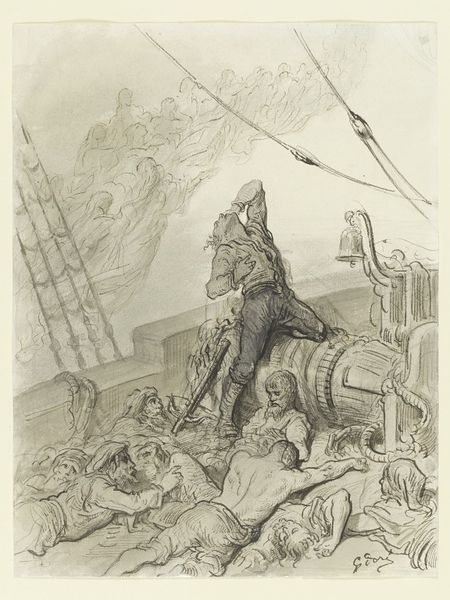

Hand-coloued mezzotint with etching. Image courtesy of British Museum.

In the context of nationalism, reverence to a figure or an event is often used to present the pride of a nation. Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, who died in the Battle of Trafalgar on the 21st of October, 1805, was important for its symbolic victory of the Royal Navy against the French and Spanish. This print is from 1806, a time after his death, but was only a part of the various items created to commemorate his death and the victory. Jewels that were produced from his death have been replicated since, as it’s not so much the man, but the impact he had in the creation of British identity and strength. The mourning industry needed to capitalise on these events for its own sustainability. A court can implement a period of mourning and influence the fashion of the time, but without the event to sustain it, the individual can mourn in their own fashion.

The early 19th century was one of discovery, change, and establishment for the world that we live in today. It’s the step into the unknown that the ship as a symbol can bring that helps us identify our own mystery.

Symbolism

Neoclassicism and jewellery led for the perfect platform to capture these emotions. Larger jewels, with oval and navette shapes of over two inches tall and ivory, paper or vellum set under glass led for the perfect canvas to design scenarios in sepia or watercolour. As the Neoclassical period coincides with the Napoleonic Wars and much of the colonial world building that occurred in the post 1760 period, being lost at sea was a part of natural life. As with the high mortality rate in the 19th century and the height of the mourning industry, integrating elements of the factual symbols of mourning into jewellery design was as literal as it was symbolic.

This is an important pendant to note, as its mourning symbolism is rich, but its application is quite simple. It stems from the early 19th century, around 1810-20, where the notion of travel had been ingrained in the popular mind. From emigration due to persecution or relocation, Britain’s colonies had been established through sea travel. To leave on a boat was effectively a signal that one would not be returning to the homeland, and this pendant captures an emotional moment that would have been rendered in more detail twenty years previously.

There’s little other allusion to context outside of the ship sailing into the distance and the Neoclassical female pointing to it sailing away. The cliff, tree and surrounds merely act as scenery, rather than enhancing the piece with further sentiments. Note the figure of the female herself. Her hair is set in a more contemporary style for the time, rather than harkening back to the Ancient Grecian idealised style, though her dress is classical in intent, but the flowing lines and folds of the dress are lost to simple strokes of the artist. The face is rather simple, the eyes are simple black dots, as is the nose, yet the artist has taken care to shade the piece and give her more contrast than the art is perhaps worthy of. Then there is the ship sailing away, note the inclusion of the flags and their colour.

It is how literal that the jewel in question presents its symbolism that one has to define its meaning. This ring has a larger story to tell in its family history, which can be read about here (Mystery Solved: Discovery of Identity Behind Ship Ring). Research is required to see how the vessel leaving relates to the subject being involved in the navy or travel, or if the symbolism is simply departure. The research done into this ring shows several generations of family being involved with its design, meaning that when the identity of the jewel is lost, then its symbolism carries through. The ship is intricately designed, being in full sail and painted in sepia. Even the waves show generous shading. This ivory disc is set inside the garter/buckle motif with the hair woven inside it and the seed pearls complete it.

With its symbolism being the primary focus of the ring, it’s clear to see why it could be used for various purposes. The ring’s assumed heritage stemming from Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Winterton, widow of the First Earl of Winterton, Edward Turnour, could be used through the family linage, as death is purely symbolic. There’s not the requirement of nationalism or physically being lost, but simply the soul departing into the unknown.

Typically, the subject of a mourning jewel in the Neoclassical era of 1760-1820 would reference a mourning female character as the analogue for the wearer. Men were infrequently displayed in the same repose, which usually show the figure painted as a personal commission. In colour or sepia tones, the painting connects the physical moment of mourning to society’s classical Greco-Roman heritage. In this ring from the Adams Historical Park, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, is assumed to have received this ring from her husband in 1778. John sailed to France with his 10 year old son, John Quincy.

What is remarkable about this sepia brooch is the quality of detail and seemingly personal artistry of the work. The dress is fashionable, with detail right down to the material in the bodice. The oak tree stands tall and strong, while birds fly after the ship on its voyage. There is security in this depiction, not at all a sadness. Charity and hope are seen in the anchor, which also alludes to a safe passage ‘I yield / whatever / is is / right’.

Compared to the brooch below, this brooch is a good counterpoint to show the personal nature of faith and sadness when a loved one travels. Identity and pride are important to the voyage of the loved one, but their methods of protection are often their own. As the United States was very young when this brooch was produced, the following example takes the same sentimentality from the British perspective.

Nationalistic pride and the very nature of death come together with the symbolism of the ship and the sea. In this brooch, Britannia and the British Lion sit on the shore and watch the ship depart. Painted in sepia on ivory, this is the typical Neoclassical design for the c.1790 period. Its design is perfectly detailed, from the flow of the classical dress to the facial features. It is the subject that is the most curious, being so specifically about the country and not the individual, yet being created as a token of memory. Britain is now the allegory for the ‘self’, in what would have traditionally been the personal identity of the mourner. It is an assumption that the jewel was for mourning, as it might have been equally given by a sailor to his loved one as a token of memory, but the sentiment is there.

The turn of the 19th century was fundamentally important for Britain and how it would establish identity. Seeing a mourning or sentimental jewel appropriate personal symbols with nationalist concepts speaks more about the culture of the time needing some consistency and security.

Nelson & the Wars

Naval might is intrinsic to the strength of a culture and its identity. During the early modern period, a strong naval presence equated to greater control of the world and the greater dissemination of a culture. Having strength in control is security for the people as much as it is the monarchy or government. As more cultures are met, more importance is put upon socio-political solidarity, as new ethnicities enter into the sphere of a country through whatever means the country influences. Flags, language and fashion become the lines that are drawn in maps to create regions that become new countries, as seen in the West.

Memorial jewellery is a big part of how this identity can be created and enforced. Solidarity during times of cultural appropriation help control dissension and enforce unity through identity.

Governments, particularly in times of political instability, can utilise a public mourning period to mass produce materials for a departed monarch, aristocrat or war hero. Jewels and peripheral items made for Princess Charlotte in 1817 led to a mass production of accessories and mourning items due to the massive public outpouring of emotion for her. Lord Horatio Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar denoted an important milestone in British history with the victory over Napoleon’s forces being symbolic. When a public event is referenced by a government, its significance is remembered, to the point where a memorial item might be replicated in future times to reignite the memory of the occasion and what it means for cultural unity and identity. Nelson’s mourning rings have been replicated on the anniversary of the battle and once more, the memory retains.

The 19th century was a period where the need to maintain a stable culture was paramount to survival. The Napoleonic Wars and change in society through the Industrial Revolution caused massive population increase in industrialised towns, which leant towards a larger issue for governments to face destabilisation. Larger populations in smaller areas could carry a message and lead to another Terror, so the investment in creating an identity was desperately needed.

Nationalistic pride and memorial jewellery are intrinsically linked. When the related death factors into the strengths or vulnerabilities of a society, then it is far more typical to find solidarity in the symbols and motifs of the country. As much of the mourning industry is predominantly British, capitalising on national elements fuels the industry itself.

This ring for Captain Newman Newman of the ship ‘Hero’ from 1811 is not just to commemorate the important loss of the ship, but also for its relation to the political climate of the time. Newman Newman was a hero of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, making him an important figure in the Royal Navy and in the public eye. These were the figures looked to for the security of the nation and their victories were the stuff of popular culture. Of the ring itself, there is the ouroboros, serpent, eating its tail, signifying eternity. Inside this eternal symbol is the Union Jack, the flag of Britain itself, visually hoisted into the air. Created in enamel, this is highly detailed and realistic for the physical construction of the ring. White, black blue and red enamel are highly detailed in their application, right down to the tongue of the serpent. For a ring that was likely replicated for the event, this piece shows the importance of national pride and the security of Britain itself.

“In 1811, as senior captain in the Baltic fleet, Captain Newman Newman was ordered to escort home the ‘St George’, 98 guns, ‘Defence’, 74 guns and ‘Cressy’, 74 guns. In a gale off Jutland, his ship, ‘Hero’, went aground and was lost with Newman-Newman and all but 12 of her ship’s company. A similar fate befell the ‘St George’ and the ‘Cressy’. It was the greatest shipwreck disaster ever on the west-coast of Jutland and a serious loss for Royal Navy. The disaster made a deep impression on the people of that time and has never been forgotten.125 years after the event, the Danish press took the initiative to raise a memorial stone which was unveiled at a ceremony in 1937. It stands on the Thorsminde tongue facing the position where the ‘St George’ was wrecked.” – British Museum

The mystery of the sea and the physical voyage is given more context with the popular figures of the time. A public lived through their adventures and offered more understanding of the world. From the earlier Neoclassical jewels to this nationalistic ring, the balance between sadness and loss for the departed loved one, and the very literal flag upon death, are two extremes of the death at sea.

Waves

Mystery, danger, love and loss are all the elements that the sea and the horizon offer. Two souls being separated and their love only growing, as they both enter the unknown requires a great deal of faith in the relationship. Even after death, having a token of memory and wearing it with the intent of remaining faithful is a beautiful and human response to loss.

Mourning and sentimental jewels play such an important part in modern identity. They created work for artists, miners, milliners and people of all trades through the various peripherals. Wearing the jewel was important for the individual, from its personal statement and even greater was the statement of the society itself. Humanity manufactures culture and asserts its dominance, seen universally through the modern period. Imperialist might through strong navies defend and increase the society. Carrying the message of love and faith in a ring, be it for the individual or the country, only stamps that message in places that have never heard of the culture.

Love and death are both the unknown, and as the ship sails into the distance, the feelings only grow stronger.