Mourning Fashion & Jewels During William IV

William IV was born William Henry on the 21st of August, 1765, the third son of George III. From the passing of George IV, his older brother, William inherited the throne much older than his predecessors, at age 64. His reign from 1830 to 1837 was short, but yielded massive change to social and economic culture. The Industrial Revolution was at its height and policy needed to adapt to reflect the changing manufacturing landscape. As such, restrictions in child labour, near complete abolition of slave labour in the Kingdom and electoral changes to the political system that accommodated for the changing population in establishing electorates.

It cannot be understated how important the Industrial Revolution was to all of the occurrences during William’s reign and just how that impacted the mourning industry. From the rise of the sewing machine, to the improvements in mechanised jewellery manufacture, artists could finance their own businesses and the beginning of the artist in fashion began to overtake a heritage or a region for owning their particular design. Ubiquitous construction methods that went with the reach of new Western settlements meant that a catalogue could be the guide for a purchase and an artist could replicate the style. Seen in the mourning jewels of this article, which show the development from c.1800 to the evolution of the style into the c.1850s, the change in construction methods to show machine turning to gold made design and development faster and more precise than ever before.

The values of the United Kingdom had been represented by the excesses of George IV, which led to the rise in a counter-cultural movement of mainstream fashion. These values can be seen in the jewels of the Gothic Revival period, as the use of bold, black enamel and ornate typography replaced the allegorical scenes of sentimental symbolism.

Mourning, by 1832, was changing its perception and values in British society. Governments, particularly in times of political instability, can utilise a public mourning period to mass produce materials for a departed monarch, aristocrat or war hero. Jewels and peripheral items made for Princess Charlotte in 1817 led to a mass production of accessories and mourning items due to the massive public outpouring of emotion for her. Lord Horatio Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar denoted an important milestone in British history with the victory over Napoleon’s forces being symbolic. When a public event is referenced by a government, its significance is remembered, to the point where a memorial item might be replicated in future times to reignite the memory of the occasion and what it means for cultural unity and identity. Nelson’s mourning rings have been replicated on the anniversary of the battle and once more, the memory retains.

The 19th century was a period where the need to maintain a stable culture was paramount to survival. The Napoleonic Wars and change in society through the Industrial Revolution caused massive population increase in industrialised towns, which leant towards a larger issue for governments to face destabilisation. Larger populations in smaller areas could carry a message and lead to another Terror, so the investment in creating an identity was desperately needed.

While the Crown had not had the command it once had since the Reformation, as most of the decisions went to the parliament, resentment of George IV through the excessive spending on arts and the treatment of a popular figure such as his daughter, Charlotte, government needed to adhere to something which could stabilise a diverse kingdom. This was ushered in through the Gothic Revival period and its use of the Rococo styling that was can be seen in architecture (such as cornices) and furniture design. Its use, combining floral and acanthus motifs, are decorative and dominating, imposing a style which was opulent upon a society that was moving away from the excess of the Regency Era and towards the simpler pre-Enlightenment Christian values. Dominance in style is a reflection of the majesty of God and final judgement, where a life lived in piety would be rewarded with entrance into heaven.

Much of this thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

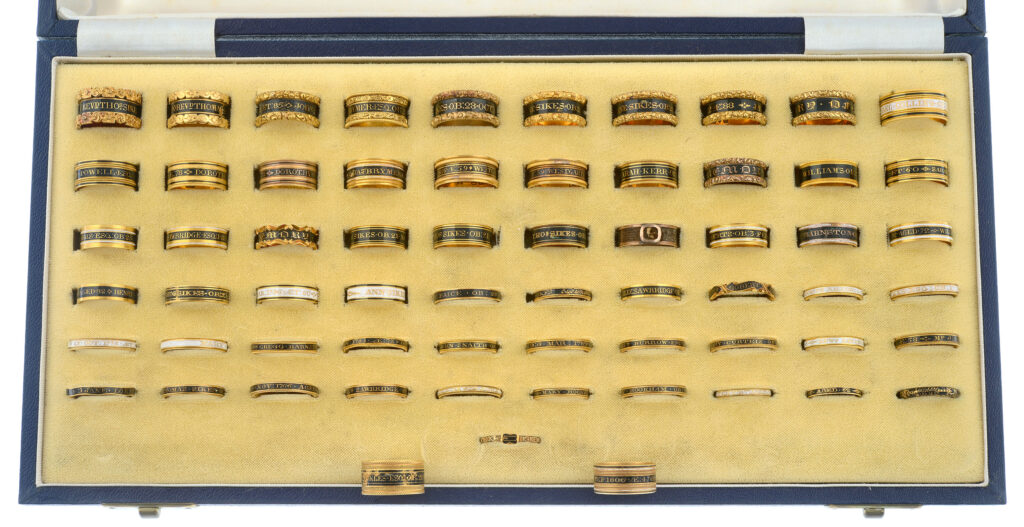

Many of the mourning jewels that are represented through the William IV period show an evolution, more than a grand change. These jewels would be the standard for what the Victorian era utilised as the basic format of mourning design. From the large, black enamel statements of ‘In Memory Of’, a ring that was designed in the 1820s was still being used through to the 1850s.

Only with changing fashion in dresses, such as the popular crinoline, the mourning jewels needed to adapt closer to the middle of the 19th century. This will be seen in a later article, however, it is important to note the various styles of the c.1800-1830 period to see the inception of these jewels.

A prime example of this ring, hallmarked from 1836/7. The ring is re-appropriated in 1851 and still highly fashionable. In much the same way that many mourning lockets are still popular mourning jewels today, the open sentiment of ‘In Memory Of’ is a timeless one that captures the grief of a family, rather than be highly specific or needing further interpretation.

Black enamel bands developed from the posie style in the 17th and 18th centuries, standardising at a time when the green enamelled ring of today took the mainstream design based upon the change of art in society.

Black enamel bands are the most recognised of mourning jewels, being placed in very visible positions for others to see, easy and cheap to manufacture and all for the purpose of creating the wearer to be a walking tombstone for the person who is deceased. Their ability to be re-appropriated or kept by a family lineage is important, as these rings are far more important as tokens of remembrance and genealogy, as opposed to their commercial value.

By looking at two different eras of mourning rings, we will see their importance as cultural markers. The following ring is from 1827:

And this ring is from 1881:

What can be gathered from the two different eras, times when the meaning of mourning and the imposition by Court values created the necessity of mourning?

Firstly, the design of the ring speaks in volumes to the society within which is was created. The first example from 1827 has the excessive flourishes around the edge of the band which were incredibly popular in jewellery design of the 1820-40 period. This was ushered in through the Gothic Revival period and its use of the Rococo styling that was can be seen in architecture (such as cornices) and furniture design. Its use, combining floral and acanthus motifs, are decorative and dominating, imposing a style which was opulent upon a society that was moving away from the excess of the Regency Era and towards the simpler pre-Enlightenment Christian values. Dominance in style is a reflection of the majesty of God and final judgement, where a life lived in piety would be rewarded with entrance into heaven. This is a motif worn on the finger to show the values of this for the deceased, who is in this case William Wrightson.

Compared to the 1827 ring, the 1881 piece is reflective of Victorian standards, where design was simplified and direct; the sentiment is drawn to the top of the ring, where the gypsy set pearls are inlaid to the stylised buckle. Post 1870s mourning jewels are far more streamlined to the Empire style, which was influenced greatly by classical elements of Roman, Greek and Etruscan in the late Victorian era, yet retained the simpler elements of each. Note the pieces below:

In contrast to the above Victorian style, the following mourning brooch with the Gothic Revival style is its ancestor. These jewels are designed to be immediately responsive towards the nature of death. Black enamel and bold lettering, regardless of the change in typography between the years of the 19th century, maintain that direct purpose:

Given that the principles of the Gothic Revival period were medieval and pious, the design as being engrained in modern values for death is not surprising. Particularly after the excesses of the George IV and Regency era, the William IV and Victorian period is a massive time of growth and change globally. The United Kingdom’s rapid expansion, and understanding of what a massive war could bring in terms of mortality, seen during the Napoleonic Wars, made the vision of death not the idyllic scenario of the Neoclassical era.

Utilising hair as the most important material began during the 1820s and 1830s, balanced equally with gems, then overtaking to be the boldest element in mourning and sentimental jewels. It was affordable, easy to weave and could scale in terms of quality. Brooches, worn at the neck, held the values of the wearer at the most prominent part of the body. Black enamelled band rings could balance well with these brooches, carrying on the style of a set in the floral borders and gothic lettering. The wearer immediately becomes a walking tombstone, a monument to the departed.

Previous to the rise of the Christian family that was popularised by Victoria, the focus of mourning jewels upon women had both a positive and negative effect. Women were introduced into the workforce, as hair working was becoming more popular, so the jeweller would work at the front of the shop and women could work behind doors, weaving hair. High mortality rates and the need to wear mourning for social acceptance and identity had some wearing mourning for the greater part of their lives. The matriarch represented the family and as fashion houses began to cater to every aspect of mourning accessory, the expenses for mourning grew.

William died on the 20th of June, 1837, leaving the succession to his niece, Victoria, who would be the last in the Hanover line . Her reign would see the mourning industry reach its apex and decline, putting into practice many of the sentimental and mourning rituals that are common today.