Culture, Conflict & Mourning in the 17th & 18th Centuries

Having a basic understanding of monarchies in the early-modern period is essential to judging a jewel and its context. Art of Mourning is a patchwork of vignettes that delve into history through jewellery and create a narrative about the reasons why a jewel was created. Much of the reason for this comes down to the basic nature of religion and the human need to know what happens in the afterlife. With the comfort that we have continuity with our loved ones in a paradise that sustains us is the reward of living a hard life. A life where the basic amenities of living were not a right, but a privilege. A life where working up a chain of aristocracy put the stress of food and material production upon the lower class, which was at the mercy of the elements and access to materials. Luther’s Ninety-Five Thesis criticised Catholic indulgence in 1517, bringing with it a level of challenge to the thought of indoctrinated religion, which spread through Germany, Denmark, Norway, Prussia, Sweden, Latvia and Estonia through advocates such as John Calvin and John Knox.

Within fashion and jewellery the jewels prior for the 16th century reflected Catholic values in love and death. With a clear understanding of mortality, final judgement meant that a life lived in piety was rewarded with an entry to heaven. This creates the constructs of the family system, relationship values and what it was to pass into death. King Henry VIII’s change to the English Constitution under the theory of the divine right of kings, gave the sovereign command over the Church of England. This English Reformation expanded his power and enacted charges of heresy and treason against those who did not follow. The bills of attainder allowed for judgement without trial, leading to executions and banishments of dissenters.

An impact so large as an ecclesiastical change has to confuse and divide a society. The change and creation of mourning rings, as well as their dedication of people in wills following the allocation of money, shows three things. One is that society could afford jewellery to be ordered outside of the aristocracy, the second is that there were artists who were relocating to or training in England in order to produce such jewels and the third is that the proximity of death was getting closer to the individual. This means that wearing the pomp of death previously was held to the higher classes, which flaunted the notions of death and judgement as being intellectual pursuits, while in the 16th century, the change to having a physical item of death was important for an individual to hold a memory, beyond reflecting of their soul in heaven.

Mourning bequeathments had been in popular thought since the late 16th century, but became indoctrinated through the 17th century. Most famously, William Shakespeare in 1616 declared that in his will that his daughter and wife should have rings stating “Love My Memory”. He also details a donation of rings to three (such as Burbage) of his acting colleagues.

Samuel Pepys bequeathed 123 rings upon his death in 1703. These rings were graded into three classes and given out according to proximity of friendship and social status. So typical as a token of giving at a funeral, Pepys wrote in his diary:

“This day my Lady Batten and my wife were at the burial of a daughter of Sir John Cawson’s and had rings for themselves and their husbands.” – July 3, 1661

The period of the second half of the 17th century was the time of the Restoration of the British Crown and a time when industries were growing to accommodate a growing middle class through technological advancements. Through this, the custom of highly produced rings led to cheaper cost. Robert Walpole, Earl of Oxford, died in 1700 and bequeathed 72 rings at £1 each to friends and family, based on the same principles as Pepys.

The token of a mourning jewel as a device of remembrance becomes ingrained within a realm of society that had not needed a standardisation of a token of remembrance (as defined by court), but the thought had seeded its way into society.

“I. THAT the two Kingdoms of Scotland and England shall upon the first day of May next ensuing the date hereof, and for ever after, be united into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN; And that the Ensigns Armorial of the said United Kingdom be such as Her Majesty shall appoint,, and the Crosses of St Andrew and St George be conjoined, in such manner as Her Majesty shall think fit, and used in all Flags, Banners, Standards and Ensigns, both at Sea and Land.” – Act of Union, 1707 / January XVI, M, DCC, VII

The Acts of Union in 1707 were the flagstone of Great Britain and the first major step towards the the division between parliament and monarchy that has remained stable to today. Without the stability of the Crown, the continuity of England as a unified state would likely have destabilised, as it is through national pride and identity that a society can maintain order through its culture and fashions. Since the death of Charles I in 1649, the instability of Catholic against Protestant rule in England was fierce, with Catholic monarchies funding a claim to power for Charles’ son James, who reigned as James II and VII from 1685 – 1688.

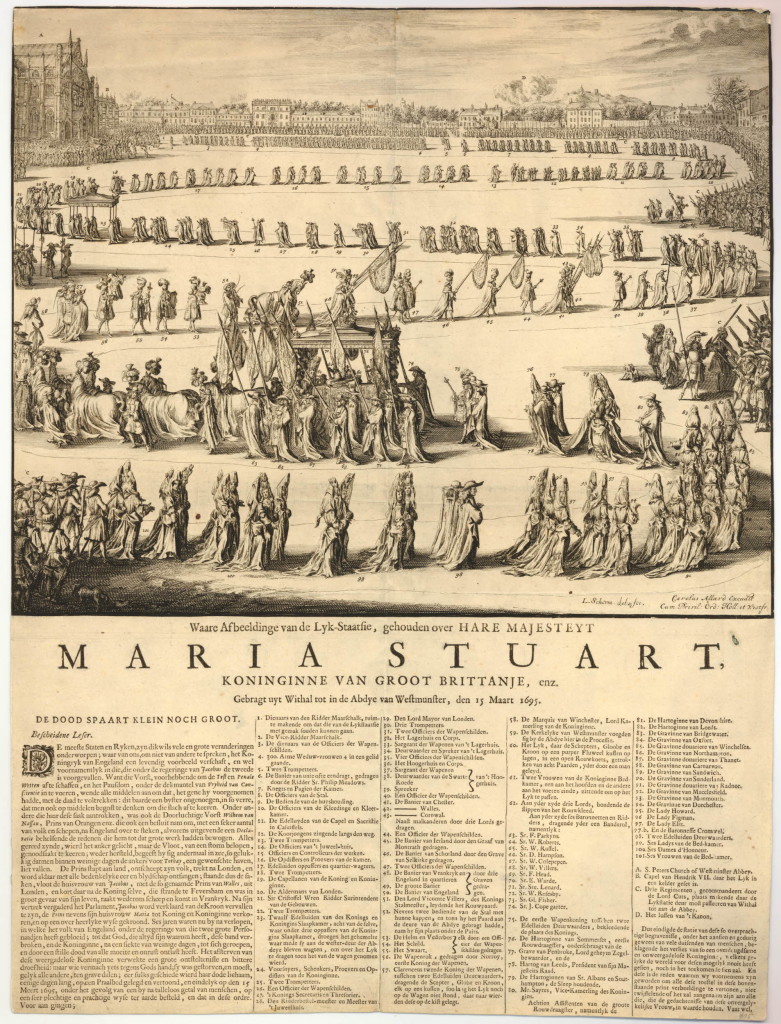

James II and VII was deposed in the Glorious Revolution in 1688, due to his Catholicism and considered to be pro-French, leading to William III of Orange to invade from the Netherlands. James’ wife, Queen Mary, gave birth to a Roman Catholic son, James Francis Edward, leading Anglicans to raise concerns about a Catholic lineage. Noblemen rose against James and he fled, then was succeeded by a shared reign of William III & II and Mary II (both grandchildren of Charles I), who were married – Mary being joint sovereign of England, Scotland and Ireland. Mary passed away on in 1694, with William becoming the singular ruler.

Mary was loved and the jewels of mortality represent this love. When a monarch passes on, the jewellery and ephemera that go along with the death reflect back on the values of a society. This commemorative slide for Mary is gold, set with a compartment of woven hair overlaid with devices of the royal crown and sceptre, two orbs and an enamelled skull and crossbones. The central gold cipher letters MR represent Mary Regina and around the edge of the slide in red and gold enamelled letters is the motto: Memento Maria Regina Obit 28 December 1694. The slide is covered with a densely faceted rock crystal. It measures one inch by 3/4 of an inch and is in superb condition, with coloured enamels as bright as they would have been when the slide was made in 1695. From it, one can judge what a contemporary jewel of the 1695 period would have resembled, just from its construction and high status in society.

This 1695 etching of a robin sitting upon Queen Mary’s mausoleum in Westminster Abbey shows a robin who gained the attention of viewers enough to have it popularised in etchings such as this. A sign of renewal and return (after a long winter), the robin is a good omen in symbolic terms, but what is more interesting is that its song related back to Mary enough to be captured in time. Without instant methods of recording, this bird was enough to be associated with Mary, who held public confidence.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYELAu9hqdU[/youtube]

Henry Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary was written in 1695, though its performance at the actual funeral is not stipulated. Music for a monarch’s funeral is not unique, however, with this and the various symbolic elements, such as the Robin, being made popularised by her death shows the resonance that she had within society. It also shows just how important she was to the mindset of society. Having a monarch that was clearly in rule stabilised and comforted a population that was under pressure from other countries and ideologies. Having the ephemera of mourning stabilises and strengthens the resolve of a community.

The Jacobite (Latin: Jacobus/James) rebellions continued between 1688 and 1746 were instigated to restore Stuart kings to the thrones of Scotland and England. Throughout the shared reign, the Jacobite resistance promoted the divine right of kings challenge to the rule, stating that the throne is a rule of God and not dictated by Parliament. Over 400 clergy and many bishops of the Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church refused to take an oath of allegiance to William III. Parliament majority of the Whigs supported William, with fluctuating support by the Tories. Wars against Louis XIV of France kept William away from England, during the time when Mary was alive, letting her govern. This conflict wasn’t resolved until the Treaty of Rijswijk ended the Nine Years’ War in September 1697. A statement of authority in William from Louis as monarch pacified the Jacobites to some degree.

James II died in exile on 1701, which makes the design quite interesting. James fled with his supporters and wife, the most of whom were Catholic. Even in his memorandum for his son, should he claim power in England, James suggested placing Catholics in positions of power, such as the Secretary of State, Secretary of War, Commissioner of the Treasury, amongst other areas within the army. Knowing that James spent much of his life under the concept of being reinstated as the English King and having several attempts at doing so through external ambition, seeing a jewel that conforms to so many popular tropes of its time is almost contrary to his personal beliefs. He died in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, but this does not mean the ring was made directly in France or even one of close proximity towards him. Mourning, or memorial rings, are tokens of memory and event, which his death certainly was. This is a commemoration in popular style for the once King of England and it shows with the memento mori symbolism, the oval shape of the ring and the faceted crystal.

(reverse) On a square tomb is seated Religion, mourning, amid various ornaments and symbols of Roman Catholicism. The front is an inscription.

Jean Dassier (1676 – 1763) was a medalist in the 18th century, who published a series of meals on the Kings and Queens of Europe in 1731. These were bronzed copper, damascened copper and silver. What is most interesting about them is their interpretation of each monarch, showing their various traits, with which they were remembered. James II’s has the trappings of the Catholic Church, showing religion seated on a square tomb with symbols of Catholicism surrounding. While these were medals presented to George II in 1731, it does show just what the public perception was for an exiled King who died on 30 years earlier.

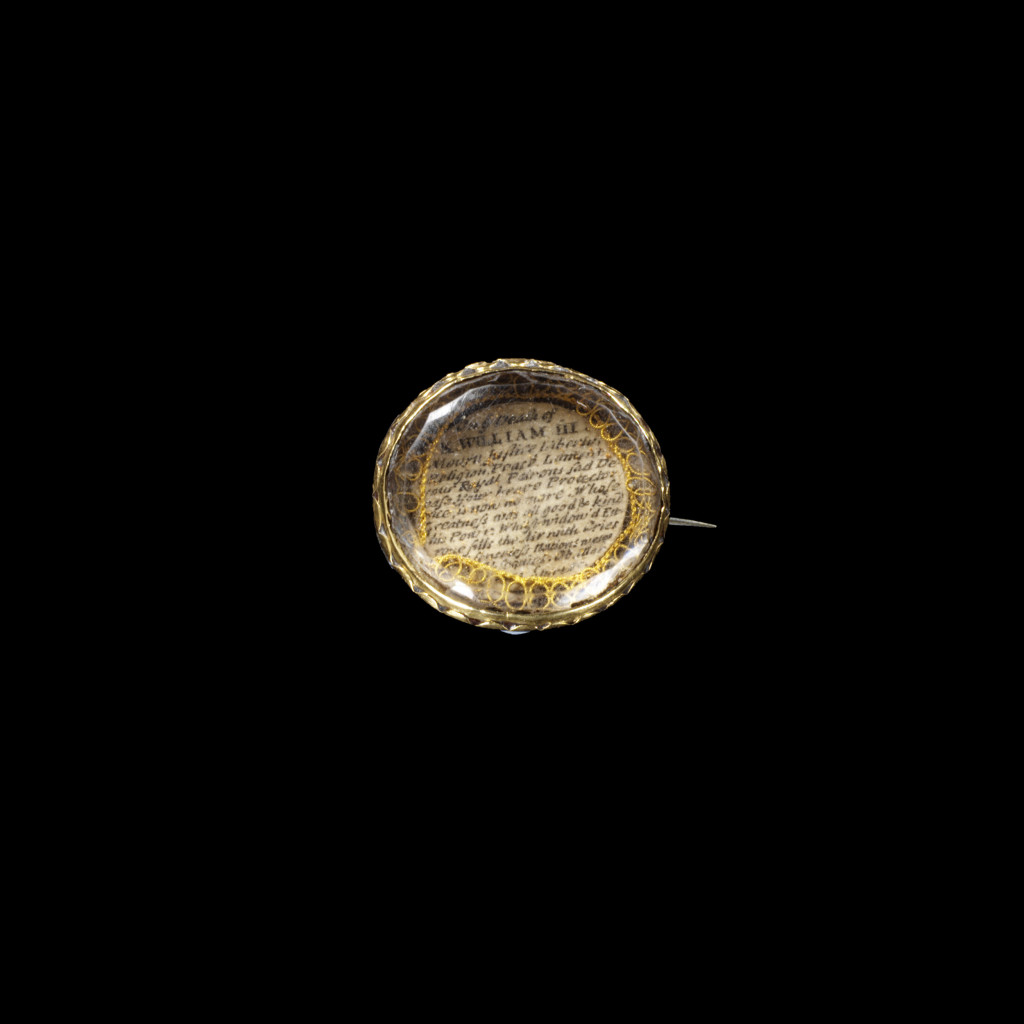

William died in 1702 from pneumonia, following a fall from his horse. His popularity at the time had waned after the death of Mary in 1695, with his not marrying or providing issue for continuing the line. The Bill of Rights stipulated that Princess Anne the only one to continue the line, however, the Act of Settlement in 1701 ensured that if William III or Anne did not have any offspring, then the Crown would go to a distant relative (Sophia of Hanover, granddaughter of King James VI) and prevent any Roman Catholic to the throne.

In this brooch, the care given to the wording is unlike any other mourning jewel that would typically be made. Its beautifully written words to the King shows an outpouring of grief which extends through Europe and maintains the strength of England. He was seen as a ‘protector’ and this reflects back on the destabilisation of Europe that had suffered for the past generation of conflict.

Through the Acts of Union, both the Parliaments of Scotland and England enabled the Treaty of Union, agreed upon in July 22nd, 1706. These Act joined the Kingdom of Scotland and Kingdom of England into the Kingdom of Great Britain. As seen through the dual titles of William, James and Mary, the thrones were separate, but had been under a singular monarch rule since King James VI of Scotland in 1603, when he inherited the English and Irish thrones from Queen Elizabeth I. Acts of Parliament in 1606, 1667 and 1689 had tried to unite England and Scotland, but these Acts under Queen Anne succeeded in unification.

Anne suffered with poor health through her life and had no surviving children. As the last monarch of the House of Stuart, she had created Great Britain, though this was not without turmoil. A two-party Government, with the Tories, who supported the Anglican church and the Whigs and favoured the commercially focused Protestant Dissenters. Anne backed the Anglican Tories, leading to internal power struggles, leading Anne as a monarch to have a greater influence in politics. In 1708, James Francis Edward Stuart (the aforementioned Roman Catholic son of James II) tried to land in Scotland, with the backing of the French, to become King. This was unsuccessful, as the English had turned them away. Anne withheld a Scottish Militia Bill, which would have armed the Scottish, but her suspicion of disloyalty prevented the arms from being turned against the English.

“Towards the end of her life Anne suffered increasingly more from gout, and could hardly walk. Having been taken ill on the morning of 30 July she died around 7.30 a.m. on 1 August 1714 at Kensington Palace, her body being so swollen with dropsy that she had to be interred in a vast square shaped coffin. She was buried in the same vault beside her husband and children, in Henry VII’s Collegiate Chapel of St Peter, Westminster Abbey on 24 August. John Arbuthnot, one of her doctors thought her death was a release of life from ill-health and tragedy; he wrote to Jonathan Swift, ‘I believe sleep, was never more welcome to a weary traveller than death was to her’.” – National Archives

From this ring dedicated to Queen Anne, the elements of memento mori and Baroque merge together to join the majesty of the Baroque decoration, with the morbidity of the memento mori crossbones, skeleton, hourglass and pick. Elements that show the desecration of the body are highly stylised, with the gold wire cipher placed on material. A ring like this can be seen several times in Art of Mourning, with rings using this as a template for the height of mourning style and fashion. It brings into immediate context how death was at the forefront of immediacy. Time flies, in the tempus fugit hourglass, the digging of the dirt and how the body’s decay around the majority of the ring shows the viewer that it is designed around death as a personal understanding in a popular culture.

Society had gone through rapid and major change over the space of four generations. From seeing the dissolution of the very religious underpinnings of society, to the execution of a king, then the instability that this brought through the European continent, death and love were challenged in ways that made the immediacy of living the most important. The loved ones that one worked to provide for and the skills that one could gain in order to improve their life was for the family. Taxes, industry and control are the ways for a culture to maintain power internally, with the roles of an individual being defined. As these started to overcome even the monarchy, the individual could place an element of a loved one in a ring or locket and feel the truth as to what life and death really were.