The Urn, Willow and Onyx in the 18th Century

The urn and willow captured the imagination of the 18th century like no other mourning symbols. Their prominence of design and utility for the purpose of mourning overtook all of the symbols of the memento mori style and came to represent death without showing the actual mortality of the subject.

Mourning is about love and identity. Without identity, there cannot be the appearance of love in fashion and this leads to a lack of memory for the loved one. Having a symbol that can instantly identify with death means a great deal to the individual wearing the symbol in society. Why the urn and willow combination work so well together is that they represent the mood of the times. Having a classical symbol in the urn represents the identity of the Enlightenment and its humanist approach to death, while the willow is a reflection upon the natural world and appreciation of the physical world. There’s no dominating symbolism that’s unattainable, such as in the previous Rococo style, which mellowed the Baroque domination of overwhelming art. A style that dominates gives the impression of judgement after death by a higher being, whereas natural identity reflects upon the peace and serenity of death in a ‘real’ world.

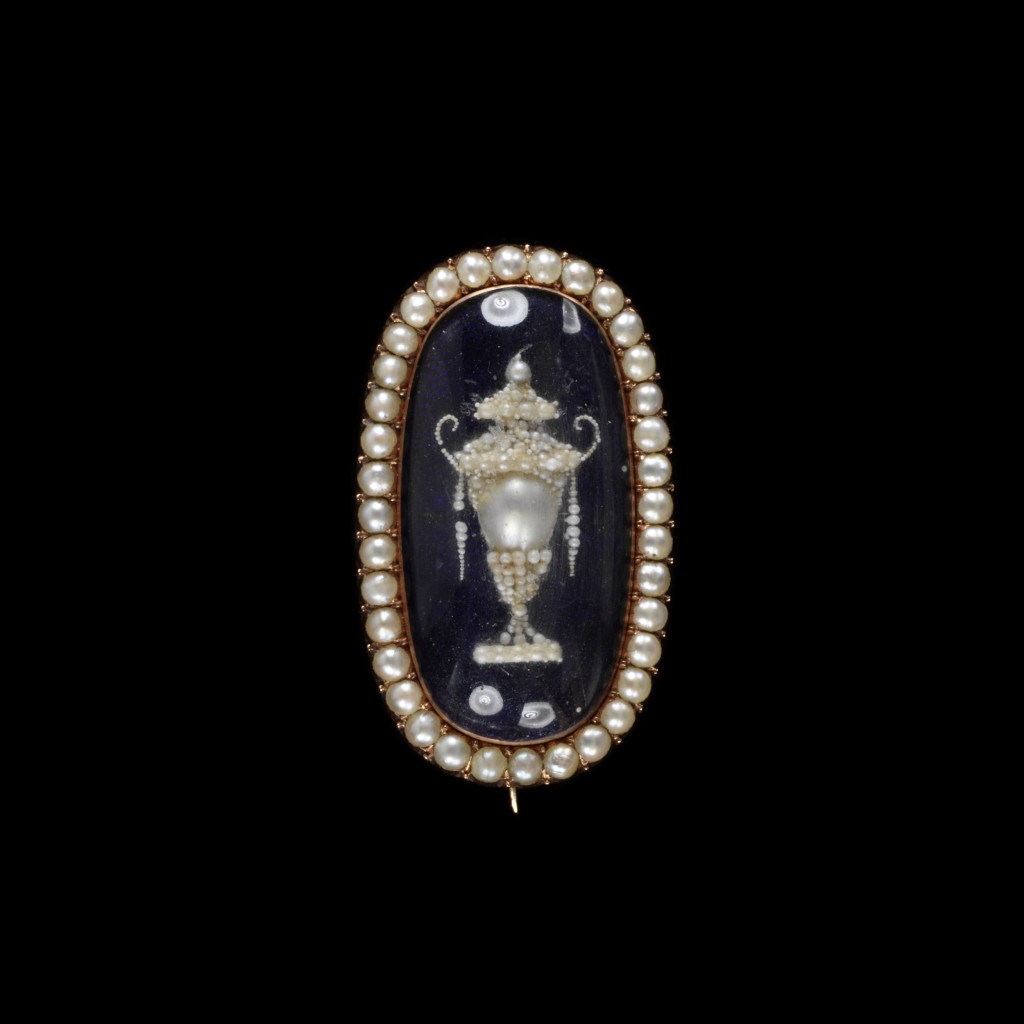

With today’s onyx cameo ring, the elements of the urn and willow emerge to the forefront of the jewel and become the only contrasting elements to the design. From its setting, the ring is decorative and transcends its time post-18th century. This is after the symbolism of the Neoclassical period had cemented itself into the mind of mainstream culture and the ring could be re-appropriated. It wouldn’t be too difficult to suggest that the ring had a dedication engraved to the reverse side of the bezel, but that has since been worn away. Even today, this would be a relevant ring to wear for mourning, not being religious or deflecting away from the serene depiction of a life cut short.

Late 18th and early 19th century fashion set the style for why this ring was produced and how it could be re-appropriated. If not for the mandated stages of mourning that were reinforced during the 19th century, fashion and culture throughout Britain would have been quite different. The 18th century welcomed in greater convention for mourning fashion and began to see the rise of the mourning industry. This became so much so that mourning dress was becoming desirable and the difference between mourning and non mourning dress was narrowing. Much of the fashion in this century was dictated by the fabric rather than the cut, and the silk industries in France and England held major influence on mourning wear because of this. It was Ordre Chronologique des Deuils de la Cour, (1765) where details of Court mourning in France were published, giving precise tailoring instructions. From their first days in mourning, men were permitted to appear in Court, unless it was after the death of a parent from whom they had received inheritance.

Widows had to wait one year and six weeks, with the first six months in black wool. Lord Chamberlain and Earl Marshall both ordered shorter periods of mourning in France and England respectively. By the 1880s in Britain, twelve weeks of mourning were ordered by the death of a king or queen, six weeks after the death of a son or daughter of the sovereign, three weeks for the monarch’s brother or sister, two weeks for royal nephews, uncles, nieces or aunts and ten days for the first cousins of the royal family. Foreign sovereigns were mourned for three weeks and their relatives for a shorter time. Mourning was divided up into First, Second and Court mourning.

Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this Industrial Revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels.

It is through the death of popular figures that mourning culture could be redefined or imposed. Mourning regulation went through different permeations in the 19th century and became longer and more rigid. It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning: ‘the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crape hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crape fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crape hatbands and black swords and buckles.’ For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear. Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

Knowing that mourning fashion was indoctrinated through systematic social integration that came from a top-down society, note the below ring from the second half of the 19th century:

Its elements are similar in classical style to the urn and willow ring, showing the same onyx cameo style and a classical broken column, symbolising a life cut short. Most telling about its age is the forget-me-not symbolism, which is quite the 19th century affectation, in use with a symbol that had its popular identity solidified in the 18th century. These symbols were retained, as they are today. Culture develops within its social and religious culture, while disseminating its identity as other cultures integrate with it. This is why these symbols are repeated; there’s not a dramatic change in the values of society, simply how culture adapts to changing technologies. Rings such as these are still popular and identifiable as symbols of mourning, even though the imposition of mourning has changed from being a rigid one. Those who feel grief can wear the trappings of mourning and still be identified with it.

Urn

As part of the dual symbolism that this ring encapsulates, the urn is the primary focus for representing the body. It is a way to capture the remains of the body and a classical affectation used in modernity that was understood for its mourning purposes. The urn itself is a vessel, or more specifically a vase, which naturally have their beginnings in pre-history when humanity began gathering items in order to carry them. We won’t be dwelling on this form of history, but rather the ancient Greek use of the urn in artistic depictions. The urn itself had evolved as a decorative item, often with art displayed upon the vessel itself prior to Greece in neighbouring Mediterranean societies, but its interpretation in jewellery design stems mostly from the Greek and Roman scenes in art and their reinvention during the Neoclassical period.

Usage of the urn had never wavered, however. Cremation of the body and the collection of ashes in the urn is a method that survived ancient civilisations well into the Dark Ages. The name itself is derived from the Latin ‘uro’, meaning ‘to burn’, so no matter what the shape of the vessel the title was always ‘urn’. This is a concept that never left the mainstream mind and its uptake as a Neoclassical symbol and its consistency as a funerary motif is simply a natural evolution for the urn’s depictions.

While burial became the more popular method of interment, the urn still retained its status as a symbol of death, testifying the death/decay of the body and into dust and the departed spirit resting with god.

Draped urns are another variation of the popular symbol in the Neoclassical period. The draped urn itself often denotes the death of an older person, however, the drapery is often a constant when in relation to death. Interpretations of this can be when the shroud drapery denotes the departure of the soul towards heaven in relation to the shroud over the body, the drape is the partition between life and death or that it is guarding the sacred contents of the urn itself. In jewellery, finding the urn draped or undraped is quite common, but why is it so?

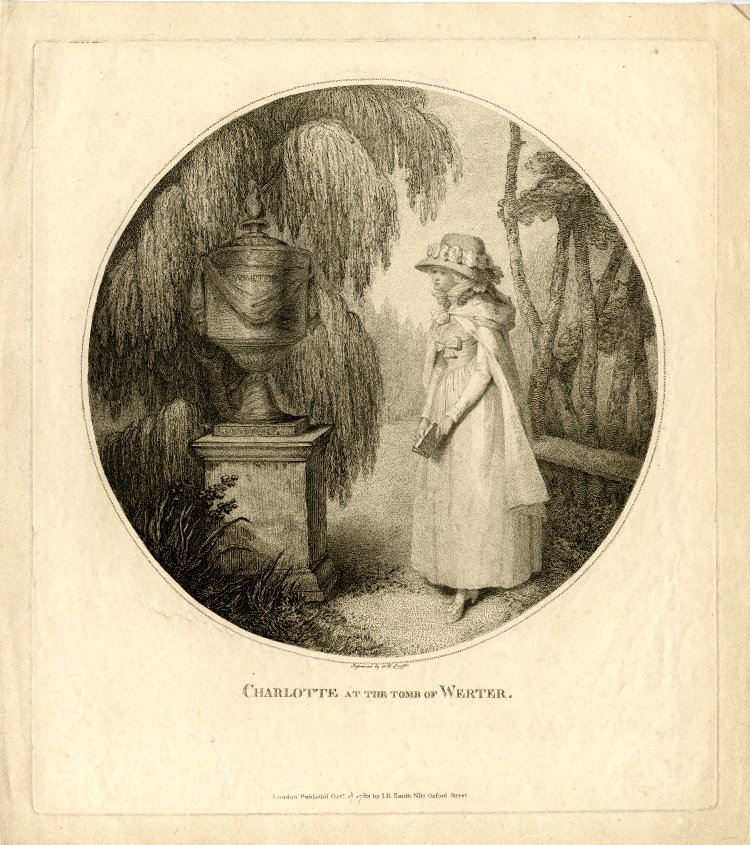

The urn is a motif that reached incredible heights of popularity in Neoclassicism due to its interpretation from the original classical depictions. It was a motif that was easily lifted from its source and fulfilled all the classical resonance that a revival period needed to convey the style of its respective era. With the focus back upon the personal nature of mourning and the departure of the direct link towards god, death itself became something worn prominently in mainstream fashion. The urn was a perfect way to show this, draped or undraped. Sitting on top of a plinth, column or tomb, the urn is often the central focus of the mourning depiction. The mourning character in the depiction (male or female) is often interacting with the urn in some way, either leaning against it weeping, sitting near it, standing beside it or looking at it directly. This links the personal nature of mourning from the person into the jewel itself. The mourner is the wearer or the person who created the dedication and the urn represents the loved one. Consider that; there’s a direct link in methodology of the urn to the self, this is why the urn is the central motif and not the mourner.

Consider that when looking at a brooch, ring, bracelet clasp, pendant or any other peripheral from the late 18th to early 19th centuries. The urn is the concept that should draw the eye and take precedence over everything else.

The symbol disappeared soon after the first quarter 19th century in mourning jewels, but was retained within funerary art. The Gothic Revival period played a key role in reverting society back to more ‘traditional’ values. Using a direct relation to the body in the urn conflicts with the burial/god connection which was part of the social understanding of life and death, that Christian values returned to a life under god.

You can find the urn in use to around the 1820s, but many of the latter uses in jewels are anachronistic in the same way that memento mori would have been during the late 18th century. However, in funerary, the urn was still retained and is to this very day. In fact, its use in architecture in the latter 19th century / early 20th century was quite typical, but it had largely disappeared as a motif to represent the self in mourning.

Onyx

Use of onyx dates back to the ancient, with reported usage in second dynasty Egypt, but most typically Greek and Roman. It is a banded form of chalcedony, with its most popular colours being black and white, yet there are multiple variations of colour found in its bands. It shares the similar jewellery carving hardstone qualities as agates, jade and rock crystal. Because the bands of onyx are aligned with each other, carving the cameo in high relief makes for highly detailed jewels. In the case of this ring with the urn and willow, there is considerable detail to the urn itself, with a very sharp styling to the willow. Note the etching to the depth of the leaves and the branches of the willow for how detailed the design is. Artists of quality could define a depiction with elaborate detail to a cameo or intaglio, where even high-relief profiles were carved to perfection. In this case, however, the carving is detailed, but not delicate, utilising many strong, sharp lines and little use of curves.

Use in mourning jewellery, for the very fact of being a black stone, is an important one. Onyx is often confused with mourning for its colour, so it is necessary to see its peripheral gems, materials and designs to note if the purpose is mourning or not. Most commonly, Edwardian and jewels through the 1920s and 30s were decorative, but are considered mourning in nature. This isn’t always so, so it is fashionable, as jet was in the 19th century.

Willow

The weeping willow is heavily symbolic of grief, sorrow and mourning, even physically, it stands as an analogy to human grief, with its back bent over the subject, be it a weeping figure, a tomb, plinth or any other mourning subject. Used in this ring, it is the second most important symbol which starkly stands out from the back background of the carved onyx. How did the willow get to be so popular and what were its roots?

One of the better descriptions of the weeping willow comes from 2020site.org and this excerpt:

“Though the Weeping Willow is commonly planted in burial grounds both in China and in Turkey, its tearful symbolism has been mainly recognized in modern times, and among Christian peoples. As has been well said: “The Cypress was long considered as the appropriate ornament of the cemetery; but its gloomy shade among the tombs, and its thick, heavy foliage of the darkest green, inspire only depressing thoughts, and present death under its most appalling image, whilst the Weeping Willow, on the contrary, rather conveys a picture of the grief felt for the loss of the departed than of the darkness of the grave. Its light and elegant foliage flows like the disheveled hair and graceful drapery of a sculptured mourner over a sepulchral urn, and conveys those soothing, though melancholy reflections…”

So, where can one find this in jewellery? Quite commonly, it became one of the most used symbols of the Neoclassical period, so look for it on miniatures set into bracelets, pendants, etc and to a lesser extent was used in the 19th century. It can still be found in cemeteries and on peripheral funeralia today.

Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787 was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow and urn here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

Neoclassical Fashion

Post 1760, the Neoclassical movement had crept into the previously fashionable Rococo style of costume fabrics. Elaborate Rococo floral motifs moved to simple stripes or smaller motifs. Side hoops were discarded and lighter silks and cotton was introduced, with much influence being from the aristocracy. Marie Antoinette was painted in La reine en gaulle, by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 1783, introducing a new style that reflected the peasantry, showing a muslin chemise, straw hat and belt at the waist.

The 18th century welcomed in greater convention for mourning fashion and began to see the rise of the mourning industry. This became so much so that mourning dress was becoming desirable and the difference between mourning and non mourning dress was narrowing. Much of the fashion in this century was dictated by the fabric rather than the cut, and the silk industries in France and England held major influence on mourning wear because of this. It was Ordre Chronologique des Deuils de la Cour, (1765) where details of Court mourning in France were published, giving precise tailoring instructions. From their first days in mourning, men were permitted to appear in Court, unless it was after the death of a parent from whom they had received inheritance.

Widows had to wait one year and six weeks, with the first six months in black wool. Lord Chamberlain and Earl Marshall both ordered shorter periods of mourning in France and England respectively.

As in the 17th century, black and plain were required. Bombazine dresses trimmed in black crape, black silk hoods and plain white linen were worn with black shammy leather shoes, glove and crape fans. Jewellery was not permitted. Second mourning consisted of black dresses, trimmed with fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black or white shoes, fans and tippets and white necklaces and earrings as necessary. Grey lusterings, tabbies and damasks were acceptable for less formal occasions.

Ordre Chronologique des Deuils de la Cour was specific and influential enough to decide upon women’s fashions, as. It was specific enough to specify that; ‘dress was cut with a train and turned back with a braid attached to the side of the skirt, which was pulled through the pockets.’ This is where the overskirt is turned to the back and lifted up, revealing the petticoat underneath, called; robe retrousee dans les poche, the centre front robings were joined with hooks or ribbons. Cuffs were cut with one fold and deep hems, the waist was held in place by a crape belt that was tied on. This left two ends hanging down to the hem of the skirt.

A woman’s accessories were a crape shawl, gloves, shoes with metallic bronzed buckles, a black woollen muff and a black crape fan. Head dresses of black crape and white batiste were referenced. For much of the century, however, ‘paniers’ were fashionable, but in the French style, with loose pleating falling from the shoulders to the back. The English manner of this was with the back pleats stitched down as far as the waistline. Also popular were lace ruffles at the neck and the cuff, embroidered stomachers, silver gilt lace, appliqué work and small aprons. None of these were permitted for mourning wear. Mourning wear for women still remained consistent in that it remained plain, black or sometimes white fabric.

Identity in Mourning

So many different aspects have come together in this ring to formulate a very special and timeless ring. Developments in fashion, popular literature, artistic application, access to onyx and Court mandated mourning are the various elements that this ring needs to thank for its very existence.

Still as relevant today as it was when it was created, it’s through the very identity of symbolism that an unspoken language can convey so much meaning. The urn and willow starkly unify above the black stone to tell its tale, while the name of the original person it would have been created for has long since passed.