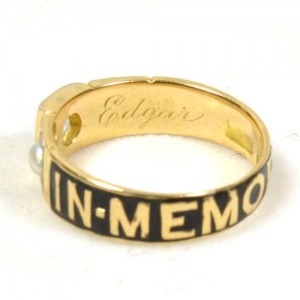

A Mourning Ring for Edgar, April 12th 1901

The late Victorian period was one of standardisation in social formality. In many ways, having standardisation or a static culture promotes challenges to the system that is accepted. By the turn of the 20th century, the mourning industry had become archaic as a fashion and relegated to being a function of society. Being in mourning meant that a family unit had to follow the stages of mourning and hold on to its trappings.

With this ring, we can see various elements of this mourning standardisation, but also we can see how beautiful this remained. Just because mourning had been falling out of favour as a fashion (due to the female imposition of remaining in mourning for family members and representing the family in mourning), the fact is still that a loved one had died and there needed to be a token of remembrance for that person. The bold ‘IN MEMORY OF’ spans the band of this ring with black enamel inlay. A gypsy-set diamond and pearls adorn the top of the ring, with the pearls being surrounded by black enamel to the north and south. Clearly, this ring represents its time (manufactured in Birmingham, 1899) in a way that adapted mourning messages into popular styles.

A Later Date

Mourning rings during the 19th century were designed to accommodate all levels of society. Due to the needs of mourning imposition and high mortality rates, pre-designed mourning jewellery was quite typical, particularly during the latter 19th century, as the methods of production had become faster with the technological improvements of the Industrial Revolution.

This ring is Hallmarked for Birmingham 1899, but the dedication is to “Edgar, April 12th, 1901”. It is safe to assume that the ring was made to the standard of a catalogue and then appropriated when the time came for Edgar’s memorial. A ring like this would have allocated funds in the will or funded by the Burial Society to be handed out to close friends and family for the funeral. Many of these rings exist and were not worn, but kept as a keepsake of the loved one.

As can be seen in the use of the pearls and the diamonds, the ring falls into line with the popular rings of the 1890s, where the gypsy setting recessed the stones into a hole in the ring and a flange of metal was pressed around the griddle of the stone. Look to contemporary catalogues to see this style of ring was quite popular. It transcended any particular reason of sentimentality and became a style universally adopted for its aesthetic quality.

In 1900

Formality in mourning was disseminated through the British colonies, leading to much of the discussed standardisation in style. Two of the most important factors to define jewellery design were from the rise of new money that came from mining and industry, as well as materials that came from this. Colonial influence can’t be understated, as it was through the British values that mourning was imposed on other culture and adversely, what was taken back to Britain created great change. Compared to the turn of the 19th century, the turn of the 20th century took the focus away from the monarchy as being the catalysts of style change, as Queen Victoria spent her post 1861 life in perpetual mourning for Prince Albert. Though this piety was very important to instilling the values of the Christian family upon society as a standard to aspire to, it also caused much interest in alternative cultures for fashion.

With rapid transit across continents being at a peak that the world had not seen before, a ring like this would not be uncommon to find in Australia, America or any culture that would support the values of the Western family. Metal manufacturing was common in Chester, Birmingham, Exeter, Newcastle, Sheffield, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dublin and London for mourning rings and other jewellery, with hallmarks being a perfect way of capturing the date and maker and the ring’s creation.

A piece could be made and exported, or taken with someone travelling or relocating. For those pieces that were exported, the base design on a catalogue was typical, as was the design in a catalogue being produced in several different areas. A ring made in the UK would similarly be produced in the USA, or where the jewellery industry could produce such a piece. With the allowance for lower grade alloys in jewellery post 1854 in the Hallmarking Act, the access to gold wasn’t an imperative, as an alloy such as Pinchbeck, which mimicked gold, could be used.

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

This ring makes use of the diamond, which was growing in popularity from the turn of the 20th century. South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

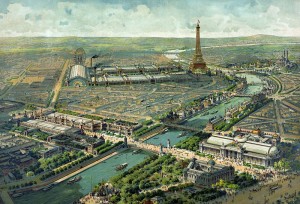

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

This is why the Paris Exhibition was so fundamental in disseminating new styles throughout mainstream culture. Wealth from America and driven by industry was empowering artists to go beyond the Court/aristocratic styles that hadn’t had the early 19th century monetary drive. Despite this new focus on fashion, mourning fashion was still engrained in the cultrual psyche from previous generations.

In Memory Of

A universal standard at the time of 1900; the ‘In Memory Of’ sentiment was engrained in the Western psyche as being solely used for mourning and this has continued today. ‘In Memory Of’ defines this ring, making it the perfect object of mourning. There is no re-appropriation of another ring for its design; it was meant to be a mourning ring and made in a way that satisfies a market.

The history of the ‘In Memory Of’ sentiment is a cross-cultural one, and one which dates to the ancient.

The piece above shows a Roman 3rd century cameo with an earlobe being pinched. The inscription reads ‘MNHMONEYE MOY’ – ‘Remember Me’. While the sentiment of mourning and memorialisation being one that goes even further before this, as long as humans have been interacting in relationship-based societies and cultures, tokens of memorialisation have been utilised. But, the ‘memory’ of ‘remembering’ the person, such as this Roman piece, show the statement from an early age. From an early modern perspective, the integration of mourning rings into wills and the statements of posie rings from the 15th century show the sentiment of remembrance becoming standardised.

By the 18th and early 19th centuries, the sentiment was becoming popular as an inscription within Neoclassical jewels. From 1765, the Neoclassical period had dominated sentimental jewellery designs with their Romantic depictions of allegorical situations, both for love and death. With the standard urn/willow/weeping female scenarios, the plinths which the urns sat upon or the borders of the pieces were often inscribed with sentiments of mourning. Using ‘memory’ as the primary sentiment was becoming popular and did not clash with the humanist view of the ‘self’ that these jewels represented. It was a term that could be utilised in religiously Reformed societies, as well as traditional Roman Catholic ones.

By the 19th century, the locket which is the focus of this article was the standard. It was a statement that survived the Gothic Revival movement and the push back to traditional Christian views which was a counter to the Neoclassical period. This was only enforced by Queen Victoria and her influence upon the family as a unit, rather than the individual as being the focus for mourning. ‘In Memory Of’ as a statement of family grief works as well as the singular person in mourning.

Placed upon rings, lockets, brooches, stickpins and every variation of mourning accessory, the ‘In Memory Of’ sentiment dominated the 19th century and exists today through the re-appropriation of jewels, on tombstones, mourning ephemera and every peripheral of mourning. It does not denote a heavy statement of grief, but rather the simple fact. The loved one is remembered.

Remembering Edgar

All this history which defines the ring is in memory of a person. Edgar, who passed away on April 12th, 1901, may be lost to sight, but his memory has rekindled the learning and understanding of the time in which he lived. So much context goes into even the most simplest of jewels; particularly in mourning. These are the tokens which represent our feelings and grief throughout our lives, so the object in which they have to be kept must be precious. In its use of pearls, the precious diamond and the enamel, we have a ring which shows that the statement of love was a pronounced one, being fashionable in a time when lesser rings were cheap and plentiful. Money doesn’t equate to a mourning piece being any more precious than another, but it can help tell a tale of a broader context for a jewel.

In the end, this ring is all that remains of Edgar and I do hope that this article has created memories for you to pass on to others.