Sister Rings for Thomas Langdale, 1790

The navette shape for mourning rings holds a fascinating connection between families of the late 18th century. Not only were these rings displaying a sentiment for a loved one, but they became personal windows into how a family mourned during the late 18th century.

Thomas Langdale passed away in 1790 and these rings are attributed to him. What is remarkable about their history sits within their design, which features remarkable elements about the designs of grief in the late 18th century. Much has been written about the allegorical mourning female in neoclassical designs; a cypher for our own emotions and a connection to British national identity, leading to Britannia. Her connection leads back to the monarch, who is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England and was used in place of the Madonna, which was used in Catholic households. Identifying the figure in a neoclassical mourning painting is to bring it closer to the values of the family and their own status in society.

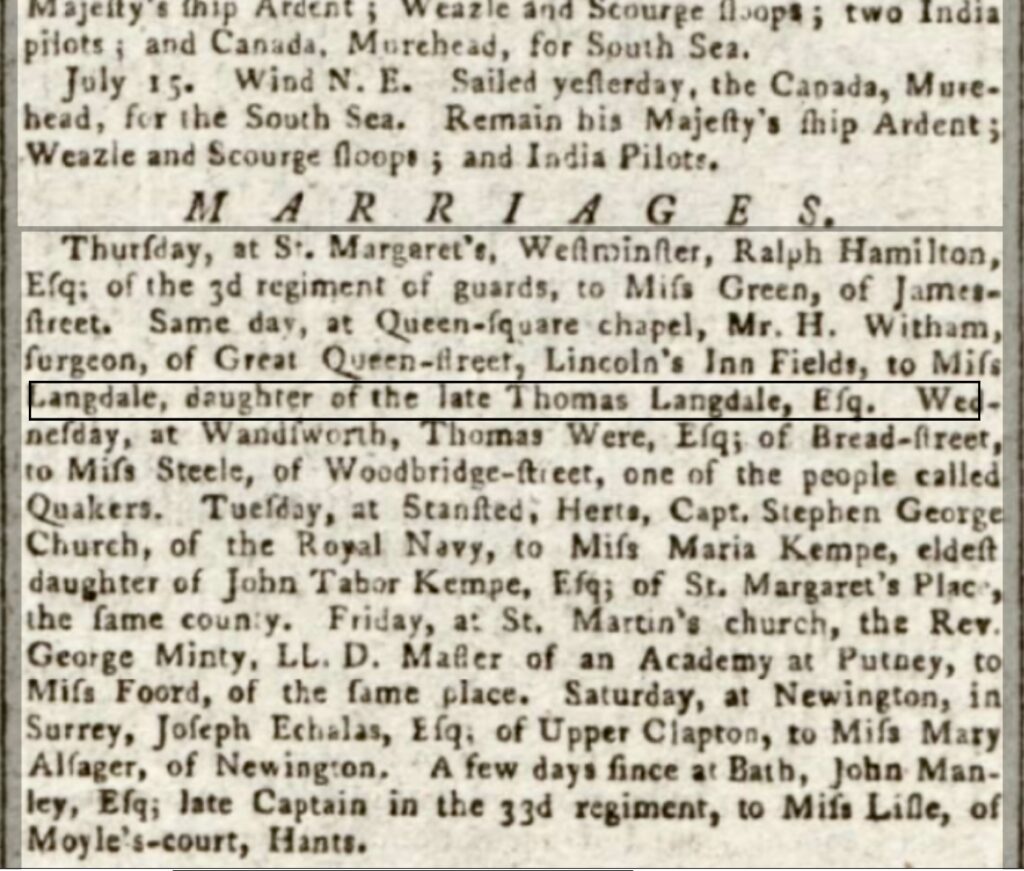

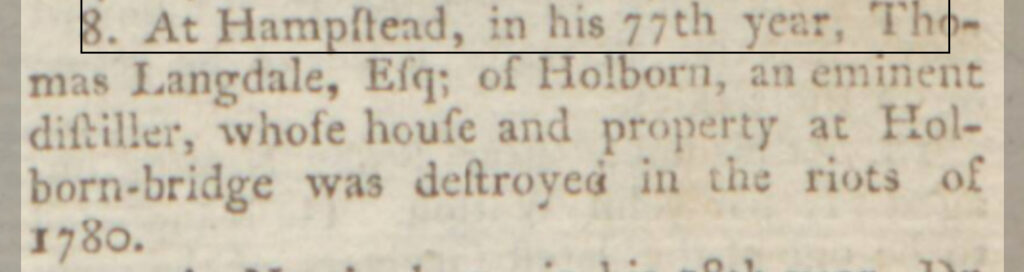

Thomas Langdale had two daughters, which these rings prove in their design. They are both equal and unique for these features, which make them very personal for the Langdale family. Originally, when I purchased these rings in the late 1990s, they were attributed to an Irish family, of which there are certainly Langdales, but the date of Thomas’ death corresponds to the reports of Langdale having passed in 1790 in Hampstead.

Interestingly, Langdale, a distiller, was known for having his house destroyed during the Gordon Riots on 1780 in London, a watershed moment that was a flashpoint between Catholics and Protestants, leading to hundreds of deaths and a week of rioting. This was a moment that challenged political values and would be referenced as a reason for British solidarity; a stark contrast to the French Revolution and global destabilisation. Indeed, it was this moment that promoted the very rings that would commemorate Langdale.

In their design, they have a series of standard elements, each of which are exquisitely produced. Both rings feature minor damage to their elements, but with both together, we can see the elements as they were meant to be. Firstly, the focus of the rings is the centralised, obelisk shaped tomb. Created from glued, ivory discs, they both feature an urn design upon the top of the tomb. This mimics a style that was referenced in the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang Goethe. Published in 1774, the image of the character Charlotte mourning at his tomb was published throughout Europe and became a favourite of even Napoleon. There is also an element of Masonic design to these ring with the obelisk, which wasn’t common in British mourning jewels. If Langdale was the very same distiller, this may be likely, but would take further evidence to discover. Many fraternal societies used their design motifs in their sentimental and mourning jewels, especially the wealthy that prospered from their trade. Regardless of Langdale’s history, these rings were certainly made for a wealthy person, as even their design adds element to navette mourning rings that weren’t typical for the time.

Langdale’s daughter rings have so much to enjoy about their design. Their use of blue enamel and opal as a border to the rings make these highly unique for their time, especially when only the use of an enamel border was considered to be the high end of mourning jewellery construction. The use of opals is an interesting one at this time, as it was highly unconventional and wouldn’t return as a popular gem until the mid-19th century. There are apocryphal stories of negative connotations with opal, but Queen Victoria was a fan of its lustre.

Painted underneath the glass is the weeping willow, another design element that was used only for the higher end of mourning jewellery designs. Most typically, one would find this style in miniature portrait designs, not as much in rings. It was easier to pre-design this element on the ivory disc, but this ring is constructed via a series of elements and painted, rather than made from just the paint itself. Even between the ivory disc that completes the tombstone of the obelisk tomb, there are two gold bars that intersect them. These rings were not made cheaply, but it is a disservice for the maker to not leave their mark on the rings. If they were, the mark has since been lost. These rings go beyond anything that you would find in a contemporary miniaturist sample catalogue and become something unique. It wouldn’t be a stretch to attribute their design to the British school, which had grown from the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768.

Unique mourning rings of the late 18th century have to be one of the rare cultural artefacts of living history in modern, western society. Unlike artwork that was created at high expensive over a long time, there wasn’t much to base mourning jewellery on, outside of a name, family value and the basic elements of a portrait. When these are combined, they offer a better insight into how the people of the time lived and their values. From what we have seen of the possible Langdale connection, there is a world of information these navette shaped rings offer us about these times.

Where these rings exceed in their importance are in the figures themselves. Note their hair and dress; both of these women are unique and are likely the representations of either the mother or the sisters to Langdale. It should be noted that ‘sister’ rings are a colloquial term for a pair or more of mourning rings, so the women involved in these may have been either. The hair styes are different, the size and stature to the obelisk are shorter and higher, as well as their positions to the tomb. These are the elements that we cannot take for granted when analysing mourning jewels, as this brings them back to the family and the immediacy of the jewel to the loved one. 19th century mourning jewels would use simple etching inside the ring, or locket, for the sake of having a hidden personalised message. 18th century mourning jewels wore their sentimentality as a display of their own self, emblazoning the ring with their own personality, message and vision.

Year: 8 December, 1790

Dedication: Thomas Langdale (age 77)