Lily of the Valley Symbolism in Jewels

The Museum of Whitby Jet is a genuine establishment of living history. Combined with the store W. Hamond, it presents the oldest connection to 19th century Whitby Jet manufacture that still exists. It is a tribute to the 1500 men and 200 shops that existed in 1873 to produce the finest quality of Jet available in the world. Their craft, of carving, turning and polishing jet held a standard that set the British Empire beyond any other jet industry in the world, being held in the highest regard by Queen Victoria herself.

Due to the popularity of Whitby Jet, the instances of its carving designs are almost infinite. The Victorians relished the romantic and sentimental language of flowers. They were educated, had access to new wealth and were the first affluent middle class that could afford leisure time. Travel was a part of seasonal Victorian lifestyle and cottage industries emerged with the connection of rail lines that ferried these sentimental people across Britain. Whitby’s popularity as the centre of Jet fed its local community and its economy. Carvers were charged with appealing to the most popular designs from the visitors, who requested sentimental tokens to gift to their loved ones.

This Art of Mourning series is in partnership with the Museum of Whitby Jet and is a look at the jewels of the museum through the eyes of the Victorians who requested and understood the love language of flowers.

To achieve this, part 1 of the series is an introduction to Whitby Jet, which can be read below:

Link > Discover Whitby Jet

Part 2 is an understanding of ‘floriography’, a late 18th and 19th century attempt by philosophers and writers to connect floral discoveries of the world to emotion to empirical fact. This can be read below:

Link > Understanding Symbolism: Botany and Floriography

Symbolism of Lily of the Valley

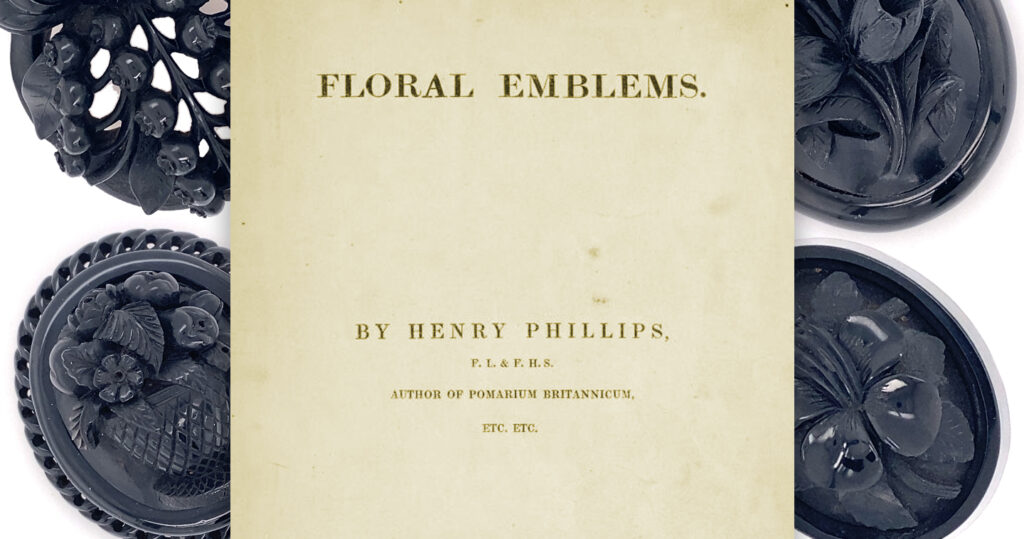

Lily of the valley was admired by the Victorians for its aesthetic value, as well as its connection to historical meaning. The flower has a demure charm that represents the same social chastity that promoted etiquette in behaviour in initialising relationships. Its growth beneath larger leaves and the forming of the elegant bell shape were seen as feminine qualities. The use of the flower in poetry repeats these values, which were catalogued and published in the 19th century. The poets Milton and Barton are referenced by Henry Phillips in 1825’s Floral Emblems, which detail the qualities of the flower:

“- and ye, whose lowlier pride,

In sweet seclusion seems to shrink from view ,

You of the valley nam’d, no longer hide

Your blossoms meet to twine the brow of purest bride.”

Barton.

This flower, whose odour is as agreeable as its form is elegant, announces the happy sea son of May, when

“- new verdure clothes the plain,

And earth assumes her transient youth again.”

Milton.

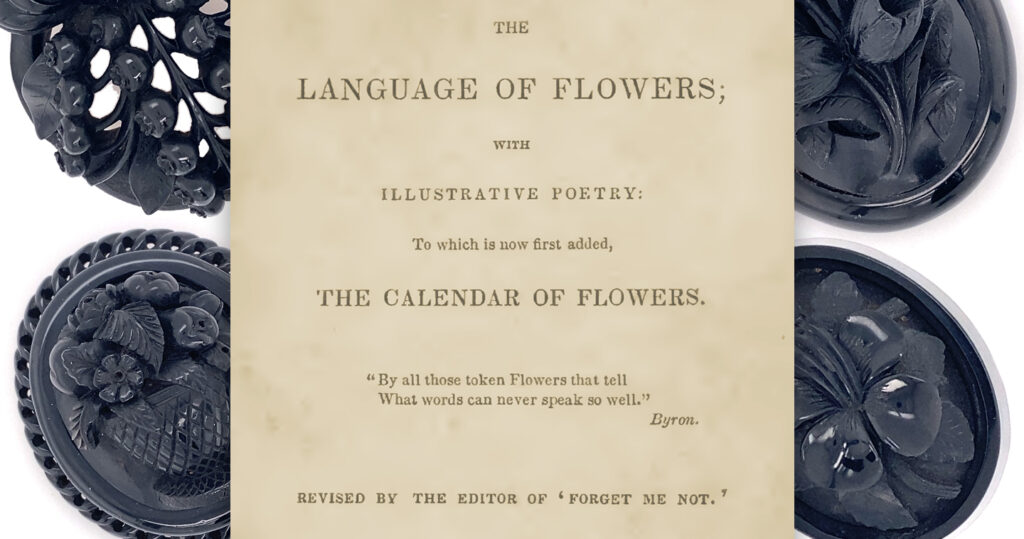

Further outlining the physical characteristics of the flower is Shoberl in 1839:

“THE Lily of the Valley delights in shady glens and the banks of murmuring brooks, where its exquisitely beautiful flower is modestly concealed amidst the broad, bright green leaves which surround its delicate and graceful bells. In floral language it is made to represent a return of happiness, because it announces by its elegance and its odour the happy season of the year.”

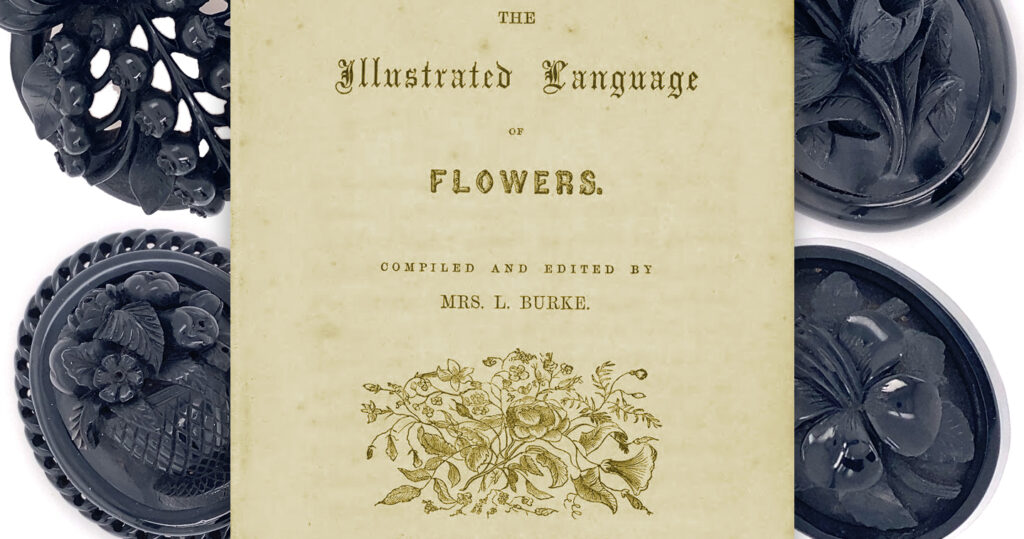

Its meaning, as outlined by Phillips in 1825, is a ‘return of happiness’, which was further justified by Shoberl in The Language of Flowers with Illustrated Poetry in 1839 and Burke’s The Illustrated Language of Flowers in 1856. Understanding the meaning of flowers and their development from the early to mid-19th century is important to see what the thoughts of the Victorians were when purchasing and giving a token of love with the floral emblem’s design. Lily of the valley is a flower with delicate qualities, appreciated for its scent and ability to easily cultivate. All of these properties made the floral design a common one for 19th century jewels, as it represents the purity and joy of a relationship.

RETURN OF HAPPINESS.

Lily of the Valley. – Convallaria majalis.

“- and ye, whose lowlier pride,

In sweet seclusion seems to shrink from view ,

You of the valley nam’d, no longer hide

Your blossoms meet to twine the brow of purest bride.”

Barton.

This flower, whose odour is as agreeable as its form is elegant, announces the happy sea son of May, when

“- new verdure clothes the plain,

And earth assumes her transient youth again.”

Milton .

“ Then the sweet lily of the vale

In woodland dells is found,

While whisp’ring winds its sweets exhale,

And waft its fragrance round.”

Floral Emblems, p.268

THE Lily of the Valley delights in shady glens and the banks of murmuring brooks, where its exquisitely beautiful flower is modestly concealed amidst the broad, bright green leaves which surround its delicate and graceful bells. In floral language it is made to represent a return of happiness, because it announces by its elegance and its odour the happy season of the year.

The Language of Flowers, p.85

Lily of the Valley… Return of happiness.

The virgin Lily of the Vale I love,

Laden with sweets Arabia cannot give ;

Distilled from liquid – music of the grove

By nightingales.

Poured out as emulous to please, they strive

In love-fraught tales.

The Illustrated Language of Flowers, p.36