1760-1800, Neoclassicism in Mourning Jewels

Facing the ideals of the Enlightenment and a new appreciation for classical history, the period between 1760 and 1800 created the underpinnings of identity in mourning and sentimentality that exist today. Politics and economics are the key supporters of popular thought; without an action or a reaction from a hierarchical body, there would be no message to proclaim or prevent. Without wealth, there would be no infrastructure to convey or afford an affectation in fashion or art. Mourning jewellery is important in modern history, as its popularity follows the trajectory of new wealth and colonisation around the world. Its fundamental importance as being a way of memorialising a person is the truth to the jewel, but the symbolism and wealth that the jewel carries is too important to be a secondary thought when worn.

Prior to the 1760s, the memento mori style dominated mourning jewels. Memento mori used visual symbolism to represent visceral death and decay, with a leaning towards the fleeting of time and the desecration of the body. It means to remember that you will die and that you will be judged. These concepts remove the living element from the idea of mourning and put the emphasis on living life being all about the outcome of the final judgement. When symbolism like this is invested in knowing your own mortality, the social values of tension on lifestyle and family values are precious, in that they will be the things that define you in the afterlife. Piety in religion is a strong way to maintain a uniform society, with much of the modern conflict and rise of individual mourning jewels stemming from religious contention between Protestants and Catholics. These identify the culture and the country that has boundaries, which is why the representation of fashion in the jewel shares the values of the individual and the state that it was created in.

The difference of memento mori jewellery to that of the post 1760s is the Neoclassical influence in humanity and art. Archaeological excavation was an important element to the growth of classical culture in the 18th century. Digs in Pompeii and Herculaneum had discoveries in 1711, but resumed with major excavations in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians. What stemmed from this was a change in how death was represented in jewellery. A major humanist movement in the Enlightenment followed the Neoclassical era, which allowed for questioning of traditional concepts of life and social structure. Since the Reformation and its impact upon religious thought, society was changing to look at itself in an individual way. Guilds, education and disseminated thought allowed for people to learn new concepts that were prohibited from earlier generations. New skills and crafts meant that an individual could break away from the family unit and learn something that was outside of the family craft. By the Neoclassical period of the late 18th century, industrialisation allowed for middle classes to grow new wealth, something the merchant classes had previously began to appreciate through importing and exporting goods globally.

Allegory in jewellery design became the new symbolism from the c.1760s. Using idyllic depictions of life and death, classical literature and art were mined for the use of any imagery that could construct a message in a painting. The sudden rise in popularity of painting on ivory or vellum, then wearing this set inside a jewel, was exponential. From the 1760s, the fundamental classical elements of mourning were created. The depiction of the female became the human ideal – the aspirational figure of emotion. The vast majority of jewels created during this time feature her flanked by an urn, broken column, weeping willow or other scenario of idyllic peace. Her dress was typically that of the classical Greek figure, featuring an under-bust dress, with many folds draping around her. Profiles of the lady also have the classical Greco-Roman nose and curled hair, creating the symbol of mourning that would last from c.1760-c.1820. Miniatures with individual portraits of a gentleman or female in modern dress and high detail are closer to actual portrait miniatures, rather than being the allegory of the female in mourning. Allusions to her being a Madonna figure are consistent with many of the Greek and Roman symbols of the time having dual meanings, much like ‘putti’ and ‘cherub’ associations, as this made for easier cultural exchange between societies which were either Protestant or Catholic. Regardless, the female is the primary element of mourning, she is the human sadness, relating to male or female. She is an aspiration, something that all society can identify with and unite behind. Much like the matriarchal figure, she is the mother of grief and the source of our own lives.

With these elements set in place, this locket is a perfect marriage of the new and the old, memento mori and Neoclassicism. Painted in sepia tones, it sets the stage for an entire scenario, which involves the very image of death and decay in the skeletal figure. Its allegory is amplified by the anachronistic element of the visual desecration of the body, which works well with its sentiment of ‘I ALONE CAN HEAL’. A powerful and grounding message that reflects back on the personal values of the wearer. These values, during a time of burgeoning humanism, utilise classical art in a way that move beyond basic religious allegory.

With her right breast exposed and the arrow having found its way to the heart, she offers this to death, who reaches out to accept. As the statement is one that is very actionable, ‘I ALONE CAN HEAL’, the message of the jewel is designed around suddenness and grief. In the idyllic scenario, there is a very strong feeling of emotional impact. The female here is depicted in classical garments and fashion, from her sandals to hair style. In the drapery of her dress, she is seen with the exposed breast, which alludes to a form of violence:

“…when the breast of a Classical Amazon or Noibid is divested of clothes, it is ostensibly occasioned by action and does not simply result from fashion, i,e a garment designed to expose the breast. Their bared breasts, above all, represent a potent visual convention employed by Classical artists to denote female victims of physical violence… Yet the female breast divested of clothes was a popular motive in Classical art, and the known representations may be divided into four categories. Certain female activities that involved either (1) breast-revealing garments or (2) divesting the female breast of concealing draperies are occasionally represented in art: running, particularly in cult celebration, and breast-feeding of children… Purposeful breast baring (2) belongs to the iconography of supplication, e.g, for mothers of grown sons… yet the earliest and broadest context for divesting the breast of clothes in Classical Greek art consists of representations of female victims of physical violence.” – Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Claire L. Lyons, Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology

She is surrounded by the two love birds and the expression of grief from the cherub/putti figure add to the values of love that have been lost. She is the ideal and the figure that is offering the heart, while remaining the strength of the symbolism. All this design is kept behind a curtain, which has been revealed for us to peer through and see what the impact of death and grief look like for the late 18th century person in mourning.

Styles and Techniques

Jewellery of the late 18th century was required to adapt in shape to house these new elements of design. It would be simple to note that jewels did adapt and change because of one catalyst, such as classical discoveries, but history is cause and effect. Supply and demand came from a burgeoning middle class, which was increasing in wealth through new education, discoveries and transit. The Industrial Revolution introduced basic machines into the household, which could increase production. As this adapted into modern industry, the rise and popularity of cities outside agriculture poured populations into smaller spaces. New techniques needed to be learned in order to operate these machines and goldsmiths benefitted from the change and demand for Neoclassical styles, but they needed to adapt.

The beginning of George III’s reign (25th of October, 1760 – 29th of January, 1820) was met with financial instability and perception over his preference of the Tories over the Whigs. Crown debt at the time accrued to £3 million, a factor that would become a common theme during his reign. Taxation would lead to the American succession, as the British felt that the colonists needed to pay for colonial protection, yet the Americans hadn’t the representation to support or reject taxation. Internally, England was seeing further contention to parliamentary rule, leading to changing governments.

With economic change, growth and instability, increased spending on fashion the arts and travel influenced personal status. Changing fashions from Europe, particularly France, were adopted into England, making Neoclassical jewels creations of what designs were aspirational. Materials that could be displayed denoted personal wealth and the latest designs changed rapidly. By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles was enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security, if fleeing the country.

Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

In 1797, the Paris Company of Goldsmiths was reinstated, after being abolished in 1791, reintroducing many of the goldsmiths from the reign of Louis XVI. By 1798, hallmarking was established in France, making it compulsory to stamp jewels under three standards of purity; 750, 840 and 920 parts per 1000. They were also stamped with a maker’s mark (the maker’s or sponsor’s initial) and symbol in a lozenge-shaped stamp.

Filigree jewellery and fine detail to gold work had its inception here, as there was as shortage of money and goldsmiths became inspired by French peasant jewellery to produce finely detailed gold with lesser materials. Seed pearls, basic gems (such as agates) were also popular, as the pearl was introduced through new trade routes to Asia. Most common of all is the use of ivory, which became the basic standard for mourning and sentimental jewellery paintings, was based in trade with Africa and Asia.

1770s

Styles of the 1770s were predominantly round in the shape of the bezel, or compartment where the primary symbol was displayed. Previously, the memento mori style had adapted to fit the Rococo designs, having natural elements designed into the gold of a ring, locket or bracelet, while the central area for the mourning or love token was smaller and faceted crystal. Glass was beginning to be used, but it wasn’t until the 1760s that the larger styles needed cheaper materials, as well as more of them, to place above a love token, such as hair. Styles of the previous decade did not change over night, with memento mori styles, curved bands and Rococo shapes being employed well into the 1770s, but they were not as popular.

As the Neoclassical period was not a singular moment of change, the 1770s continued with the Rococo elements, seen in the above ring. One thing that the Neoclassical period was very effective at doing, was introducing geometric shape and simple lines into the styles of the jewels. Seen in the below ring, the band did not disappear from mourning jewels, but simplified into being a straight line:

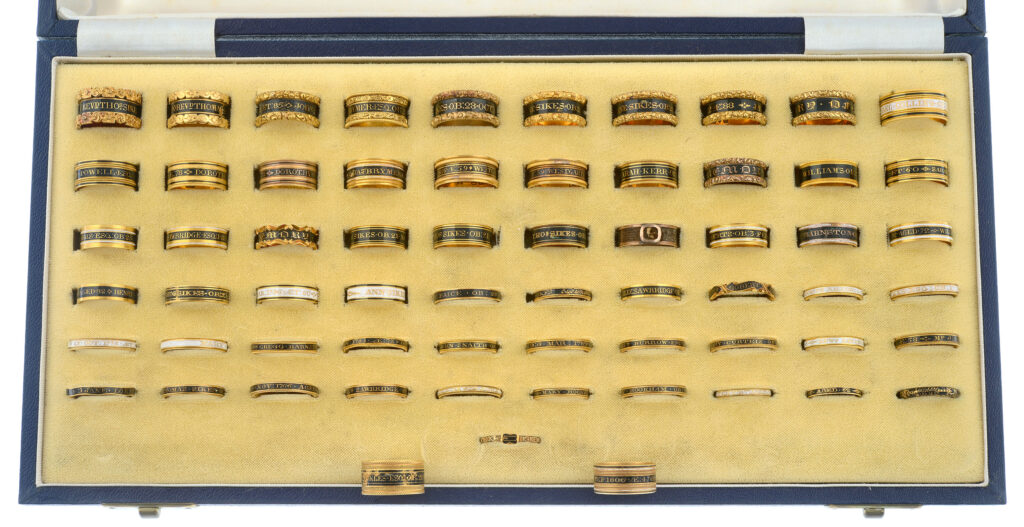

Round, level shapes in Neoclassical jewels are important, as they influenced the round shapes of the bezels that would hold the larger designs and art of the Neoclassical period. By the early 19th century, larger rings and pendants began to lose their appeal and the simple band design or oval shape was the fashionable design standard. The late 18th century, with its excessive designs in mourning jewels are important to focus on for their mass popularisation of symbols. It was the person who became the walking canvas to advertise these jewels in society.

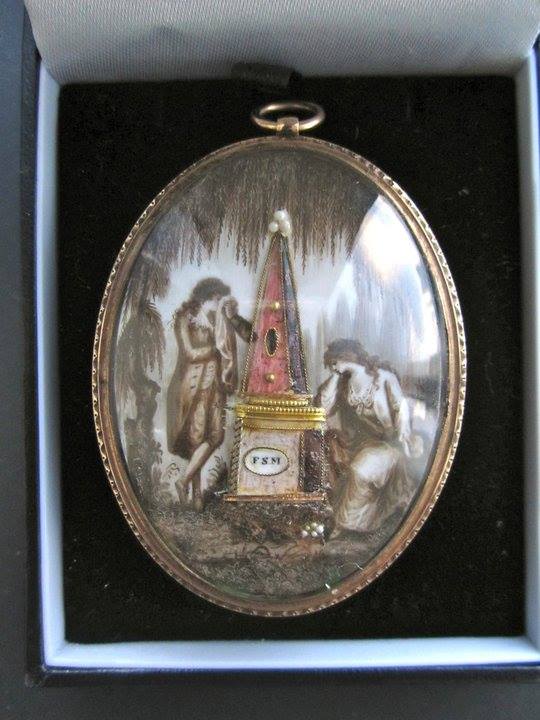

During the 1770s, there were a variety of styles that all tried to become the universal standard of the Neoclassical period. Due to the high demand of the mourning jewels, artists pushed into areas of design that utilised popular symbolic elements and arranged them in a way that was obviously for mourning, but unique to their own artistic styles. The use of crushing hair into paint, or using hair to construct high-relief objects inside jewels was a popular way to create a three-dimensional urn or willow in jewels. In this ring, the urn has been constructed from this method, glued to mother of pearl glass and surrounded by white enamel.

Stitching with hair was another way of integrating a sentimental material into mourning jewellery. In this 1775 bracelet clasp for Margaret Sinclair, much of the detail is at the mercy of the stitch work. Having a larger canvas in the clasp itself, the detail of the stitches enhance the crisp design, which a painting with sepia could possibly blur. Symbolically, this urn relates quite intrinsically with the dedication at the reverse; Margaret died in Lyon, but the eternal flame burning above the urn will keep her memory and spirit alive forever. Its detail, with the three-dimensional flames, are sharply stitched, beginning with the lower level flame to the higher level, resonate with a strength and power that is growing and not waning.

1780s

In the 1780s, different styles were toyed with in the shape of the love token’s placement. These would fluctuate until the 1790s, when a new style would become the universal standard. The love heart would find much of its basis in this period of jewels, as the shape was elaborated upon and took on the familiar aspects of how we recognise its symbolism today.

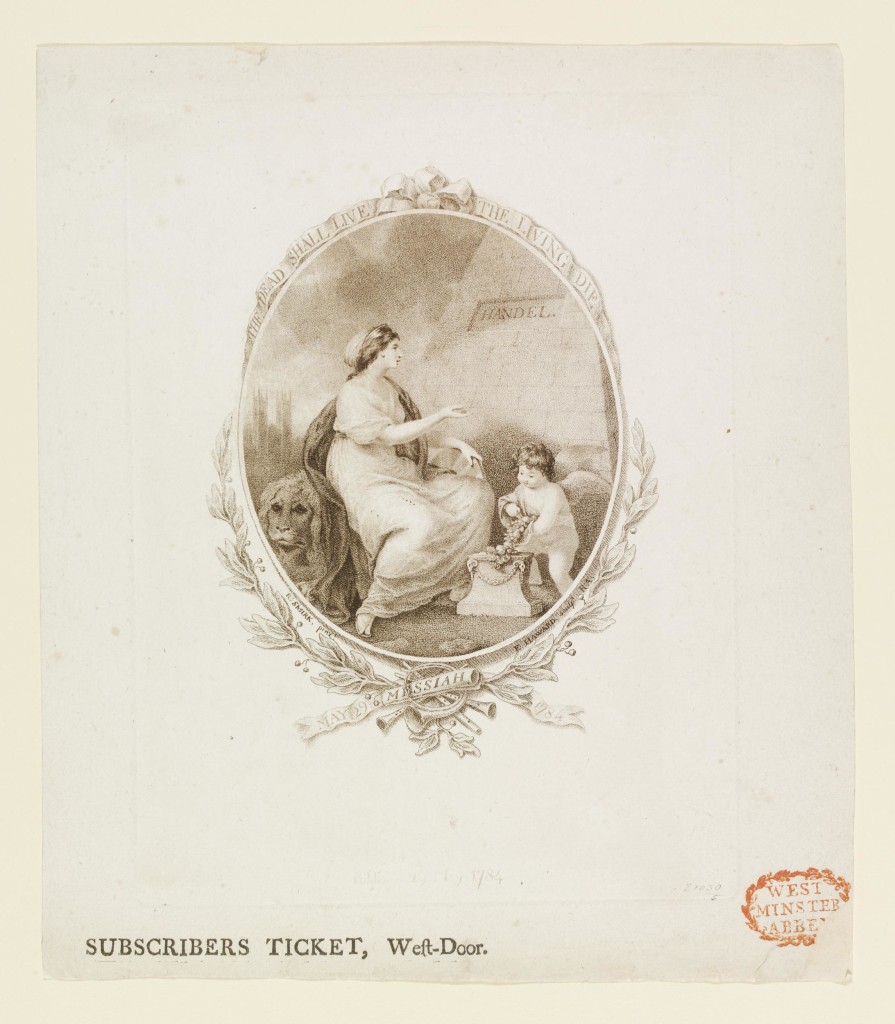

This ticket relates to the design E.1228-1948 in respect of the principal figure at the tomb but there are many differences. Image courtesy of British Museum.

Popular themes of the late 18th century became part of mourning symbolism. Beyond simply the features of what mourning aspects reflect the values of life and death, the popularity of symbolism in daily life is reflected in jewels themselves. Allegorical design and popular fashion allowed for mourning to be a part of daily fashion, rather than simply a socially imposed ritual. An example of this can be seen in George Frideric Handel’s ‘Commemoration’ in 1784, which was an event to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the composer’s death. Symbolism in the design of the ticket utilised the popular motifs of the time, complete with religious symbolism in its mourning values. With art by Robert Smirke and engraving by Francis Haward, the inscription of ‘THE DEAD SHALL LIVE / THE LIVING DIE’ reflects chorus of Handel’s Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (the following line being ‘And music shall untune the sky’). The female figure is once again flanked by the cherub, who is placing flowers on the plinth and has a sad expression. The female has a lion behind her, reflecting resurrection (as there was a belief of lion’s sleeping with open eyes having a comparison with Christ in the tomb) and the tomb to the right. Compare this symbolism and design with the following pin:

It is almost a facsimile of the Handel design, painted on ivory. The artist has used the same symbolism, poise and character design as what was popular for 1784. William Mount passed away in 1784 at the age of 26 and this was a brooch to commemorate his death. As a popular motif in design, this is why the elements of Neoclassical art are so important to the values of the time. Used for popular events, such as the Handel Commemoration, they were symbolically popular in society, so the presentation of the symbols is easily recognisable. it would not be difficult for these to be produced in higher volume and disseminated to jewellers, then tailored with the inscription upon the reverse, for the use in mourning.

Round shapes in jewels were popular during the 1780s, as different forms of art could be placed inside. Known as ‘black shades’, silhouette artistry was popularised in the late 17th century. Freehand scissor cutting was the popular predecessor to black profile painting, with sketched outlines taken of a subject after a few seconds of studying a sitter. After a pencil or pen sketch, a small likeness was cut. Elizabeth Pyburg is one of the earliest recordings of English artistic cutters, cutting a profile of William and Mary dated 1699. Not one particular style is known to popularise or create a conventional standard for silhouettes, with all methods from glass, ivory, plaster, Indian ink, oil painting and smoke-staining used in overlapping times. This was the inclination of the artist or whatever methodology was popular and would create the greatest revenue for its time. Miniature shades found in jewels were incredibly popular from the 1780s to the 1820s, following the trend of the Neoclassical period to capture the ‘self’ in sentimental jewels and keepsakes. This carried over the idealism of the Enlightenment and the challenge to allegorical depictions of identity through ecclesiastical symbols. It also was part of the accessibility that a mobile society had access to artists who could produce these jewels at a reasonable cost.

Popular for souvenirs as their construction was fast and cost effective, artists would establish themselves in tourist places such as Brighton or Bath or public events, creating keepsakes of entire families at a rapid pace. This was from a variety of skills, being either rapid cutting of paper, quickly tracing or free handed interpretation.

It is said that the name ‘silhouette’ was taken from Étienne de Silhouette, an amateur artist who was also the French Controller-General of Finances under Louis XV. As a method of ridicule, the name was used to parody his management of finances after the Seven Years’ War, reduced spending and taxes. Hence, the method of cut paper shades being ‘cheap’ were called ‘silhouettes’, but the term was not commonly used until the early 19th century.

The central motif of the mourning symbol became popular during the 18th century, with the element becoming its own construction, rather than being part of the design. The urn, in this stickpin, is seen as the only element of the stickpin and its primary focus of being for mourning. There is nothing more that this jewel needs to display, as the urn is a powerful enough token of mourning that having several symbolic elements is redundant. What this shows is the popularity of the mourning industry in fashion – it’s an element that doesn’t need mourning as a brand, it’s a functional item, but mourning could be designed within any token or accessory for daily use.

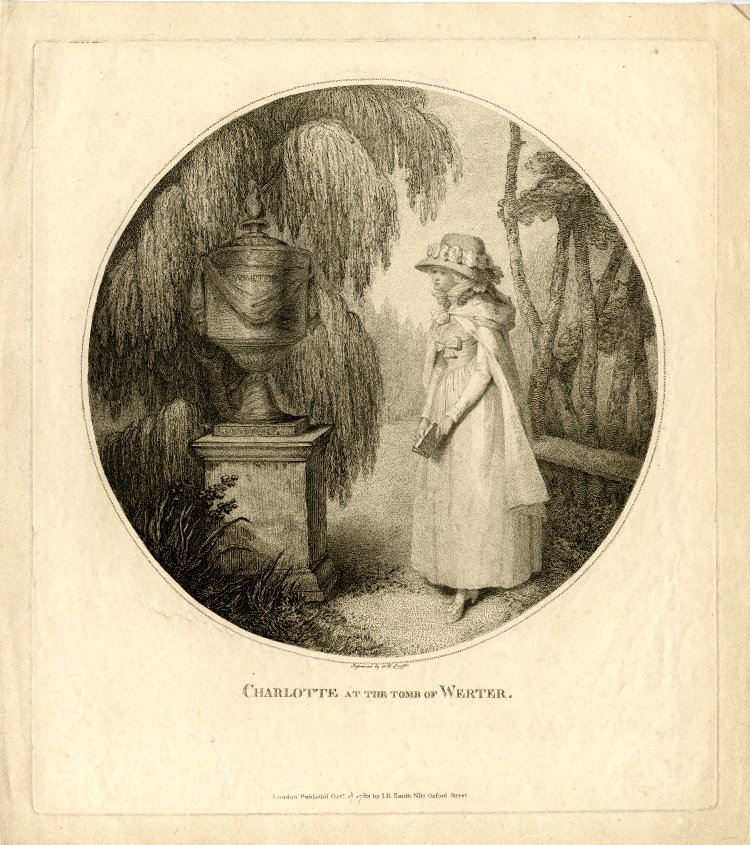

Popular culture was intrinsic to the rise of fashion and art in the 18th century. As previously seen in the Handel jewel, elements of mourning cross-pollinated from literature, music, art and fashion into jewellery design. In the above stoneware with blue jasper dip and applied white stoneware relief, the ‘tomb of Werther’ was based in popular culture. Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787 was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow and urn here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

Access to wealth, styles that could traverse continents and a younger generation growing up in this society all affected Neoclassical jewels. the symbolic value of a mourning jewel still retains its intrinsic elements of grief, but they go beyond this into the affectation of fashion. Simple grief is not enough in a period of increasing personal human interest, the fashion of it is required to present back into society and promote the status of the individual. In the 1780s, this reached new heights, creating the basis for the more necessary mourning jewels that would be employed during the European destabilisation of the 1790s.

1790s

The 1790s are best known for their use of the ‘navette’ shape, where the love token’s placement is within a shape that had a tall north-to-south area. This style was most typically used in bracelet clasps, rings and pendants. As an accompaniment to this, the popularity of the miniature portrait used an oval shape with an ivory disc inside to provide keepsakes, often at a higher quality. Miniaturist schools grew with the investment of new wealth, allowing for an increase in miniaturists and the availability for miniatures not to be just accessible to the aristocracy and monarchy.

The 1790s were about refinement and production. The earlier displayed styles did not disappear, they simply evolved. The design of the female, urn, willow and all peripherals were perfected to the point of standardisation. The ‘navette’ shape was the perfect standard size to have the willow flank its border and the central element, be it the tomb or urn, were on display as the focus of the jewel. Larger miniature styles could be carried in compact cases and carried with the individual, or displayed in the home as required. As can be seen in the above ring from 1791, this sepia painting is the standard for mourning elements in the late 18th century. The willow, urn and plinth are all standard, painted on ivory and show the tall north-to-south navette shape. A ring like this could be purchased, with the reverse engraving being made at the time of commission.

Construction methods still underwent experimentation in the 1790s, but there was more of a template to work from. This urn ring from 1791 is enamelled in black and features the urn as the central element of symbolism. The hoop with shoulders and bezel form two hands grasping at the urn, which is hinged to reveal a locket fitting for hair. It is engraved inside with initials ‘MP’, a London hallmark for 1791-92 and maker’s mark ‘WK’., England, 1791-2. Use of the locket in a ring was being experimented with through the turn of the 19th century and would continue to be one of the more popular designs during the 19th century. The giving of hair as a symbolic gesture, be it alive or dead, was amplified by Queen Victoria and moved hair from being a more hidden element to the prominent focus of the jewel. For the 1790s, this ring is a perfect representation of sentimentality in mourning, with the addition of the hands, it amplifies the symbolic message.

In the above pendant, the use of pearl and ivory creates the mourning scenario, which is far more esoteric than the standard. Value of the jewel could scale higher or lower, allowing for greater detail in the more affluent pieces. The inscription is ‘Henry Halsey Inft. aged 10 Mos. died 12th Jan 1798.’ and ‘Fond Parents grieve not for thy Infant Son Your God has called him and his Will be done.’ Pieces for children and the use of white in enamel, have more immediacy to their design and requirement. Sudden deaths have less time to plan for, as burial societies would be paid a year on year fee to cater for the burial and its peripherals, children did not have that luxury.

At the end of the century, larger styles displayed highly detailed miniatures. The classical figure was designed and could be tailored to the individual. Typically, it is the sentiment that was tailored, often seen in the change in design of the wording to the art of the piece. Set in gilt copper, this sepia-painted on ivory brooch shows the women beneath the willow, mourning at the urn and plinth, inscribed with ‘Sacred to the Memory of Dear Parents’. Dimension is an important factor in 1790s mourning miniatures, as there is a greater allowance for detail and depth of perspective. Note the detail to the painting underneath the glass, which pushes a foreground and background effect to the miniature work. Pre-designed styles like there were typical from the 1780s to the 1820s, with travelling miniaturists having the ivory discs painted and amended upon purchase. With Neoclassical styles having an idyllic depiction of the facial features, even miniatures of individuals could be tailored in hair and eye colour.

Colour is another element that the 1790s are popular for using. The sepia tones, denoting the body and the earth, were the popular mourning standard, but painted colour was used more frequently in the 1790s. It added another element to the mourning standard, as seen in the above locket. This jewel is an enamelled gold frame enclosing a painted miniature, embellished with ivory, gold foil and hair, of a woman seated by a column and a angel pointing to a label inscribed ‘Weep not, it falls to rise again’.It is all in high relief and represents the pinnacle of the 18th century, when the allegory begins to eclipse the actual person in mourning.

End of the Century

The 1790s held great destabilisation for Europe, removing much of the focus of power from systems of government and putting them upon the individual. From America succeeding to the French Revolution and global colonisation, traditional systems of power were struggling to maintain consistent identity that a public could identify with. Mourning, as a fashion, is intrinsically personal and about the self. Having an identity in mourning is as important to a culture, as the visibility of the person in mourning represents the family and its ideals. With these ideals, religion and government follow.

Having a distinct language in mourning fashion could identify a culture around the world, with people bringing their own traditions and values with them as transit and colonisation increased. The late 18th century was the inception for what these symbols of death would be throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as the art was replicated in cemeteries and funerary art. The global standard is reflected in the jewels, from the urn and willow to the female mourner, they are as timeless as the Greco-Roman world they are trying to reference.