Art of Hairwork 1: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Serpent Clasp

Discovery is one of the most enlightening and exciting elements to collecting and understanding anything antique. With jewels, there is no limit to what data and learning we can extrapolate from their construction, their design, their materials and how that brings us one step closer to a time long forgotten.

One of the more overlooked elements in jewellery, and as a material in general, is hairwork. Hairwork holds a fascination with some and a the macabre with others; the irony being that the majority of hairwork jewels produced were for sentimental reasons and not mourning.

It was a material that could be worked to become as fine as silk or as strong as any rope, a durable keepsake for a loved one that could be presented as a fine jewel or worn as a daily accessory. This is why hairwork needs to be understood in a greater capacity by not only us, but by those around you.

So, let’s begin in the most humble of places. Let’s look to this 19th century fob chain and learn how it was made, as well as how to spot the jewel and put it to a year that will fit right into your collection! For this, we will acquire the help of Mark Campbell and the brilliant ‘The Art of Hair Work’ (1875) to help us along the way.

The first thing to look at with fob chain, ring, necklace, bracelet or any other form of hairworking jewel are the fittings that surround it. There is so much to be extrapolated from the style; it could be Gothic Revival, Rococo Revival, Etruscan or any other form at the time; these are the elements that at least will put the jewel in the era that you can define it.

What is the first element we can see on this clasp? Certainly, it has to be the serpent! This symbol is an ancient one and if you’re a collector of the mourning and sentimental, chances are you’ve seen it in jewellery going back to the 17th century. The serpent can be found swallowing their own tail, which represents eternity, often to ‘love another for eternity’ (if the piece is dedicated to someone or from someone), also rebirth and immortality.

Powerful statements of love and powerful statements for the self.

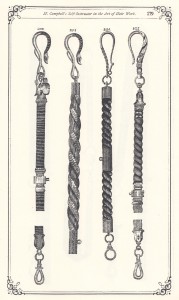

Let’s now look to Mark Campbell’s catalogue for the fitting type and we can see a remarkable similarity with styles that were popular at the time. Obviously, the serpent is the most prevalent, yet we have the twist, seen in f.255 with the could around the base of the clasp and the tighter coil that relates to f.254. Yet the head of the serpent is much like f.252/3 in that it should the actual serpent winding up the clasp itself. This is a standardised style, a style that had been engrained with the mainstream fashion, no doubt with any help from Queen Victoria, who had a keen affection for the sentiment.

Following this, the braid comes into examination. From here, it’s best to look to Campbell as the entwining details are in the construction:

“Double Rib Chain Braid.

TAKE twenty-six strands, sixty hairs in a strand, and place them on a table like pattern. Commence at A and B: Take Nos. 1 and change places by swinging them around the table to the left; then take the third strands to the right of A and B, and change places by swinging them around the table to the righto then take the fourth strands to the right of the ones last taken, and change places by swinging them around the table to the left, and so on, working around the table to the right; first swinging the strands to the left, and then to the right, taking alternatively the third and fourth strands to the right of the ones last used, until the braid is finished.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire , and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire to the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end of keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

And here we have the methodology of the hairwork itself. We have an understanding of its construction and why it would be used as a chain, with enough elasticity to hold heavy objects; such as a pocket watch or male accessory. Always look to the hairwork in your jewel to identify it; Campbell gives some wonderful insights into the advancement of hairwork, as well as the era of their respective constructions.

In our next article, we will go through the Directions for New Beginners and understand what Campbell was explaining through his description of hairwork weaving.