Art of Hairwork 4: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Acorn Charms

There are several elements here that are intrinsic to Victorian style and fashion that represent the person, that involves not only hairwork, but symbolism itself.

With this fob chain, a fashion accessory that was as essential to men’s fashion as would be the presentation of mourning (though this is a sentimental piece), there are pieces which combine to create a whole. There is the pearl, the garnet, the acorn and the hairwork, forming a union between symbolism and material that could be used as a part of daily fashion. But why was it constructed, how was it constructed and why was it worn?

Let’s first look to the fittings, the first thing that a collector should be analysing. Here, we have signs of wealth, due to the use of the pearl and garnets, as well as the bespoke charms. It should be noted that this is requested by the person who bought the piece, as each element could be chosen from the catalogue to assemble the desired combination of sentimentality for the chain. A gentleman’s accessory was built around the fob chain, as this housed many of the essential elements for daily use, such as the pocket watch, hence the use of hairwork is the primary element that draws this back to sentimentality and its purpose in late Victorian culture.

WIth higher catalysts for change in fashion during the 18th and early 19th centuries, the latter 19th century had a very fixed view of mainstream fashion, with many underlying and peripheral art movements growing in their own right. Yet, just because movements happen over a period of time (such as the Arts and Crafts movement), this does not mean there is a clear change in fashion over a short period due to a single event. Generations grew up with the paradigm of fashion (royalty) dictating the nature of fashion and with Queen Victoria remaining in mourning from 1861, we have expansion of an Empire at an exponential rate, but only elements of this showing through within the culture. This is within the areas annexed and bought into the British Empire that could influence the culture (such as India); everything from food and fashion was affected by this. Though there was bleed-though from to the tastes of the aristocracy, it did not affect the proper nature of what could be worn at court or presented as the fungible way in which a person presented themselves in a passionate way, be it mourning or sentimentality.

Hence, this is why such a simple fob chain can be seen as a culturally important element of daily life for its time. This is how a gentleman would be presented and the smaller pieces to this fob chain reflect that persona.

The fob chain is an important as it was functional and defined fashion. Indeed, men’s fashion could be discerned by the number of button holes that shown the provided the anchorage for the chain. This would denote the number of accessories attached to the chain, and hence, the wealth of its wearer by the number of accessories and how the tailoring of the costume could be defined around it.

“The way in which watches have been worn has changed ver the years and they are as much an indication of wealth today as they were in the sixteenth century. From the time of Henry VIII it was fashionable for a monarch to wear a watch as a pendant at waist level. A skilled watchmaker could even make the watch in the form of wring. In the seventeenth century Samuel Pepys reflected in his diary that how a watch was worn gave an indication of the wearer’s character. Since its invention the watch, with its chain and attachments, has been the most decorative item worn by a gentleman. From Georgian times the chain was worn diagonally with a bolero style of vest (later called a waistcoat). The chatelaine (an ornamental chain hanging from the waist to which ,keys, seals and similar objects were attached) was worn by both men and women at this time and the skills of jewellers and goldsmiths were lavished on it.” (Gentleman’s Dress Accessories, Eckerstein, Firkins, 1987)

So, now let’s look to the acorn motif and let it reveal itself upon the gentleman.

Great oaks from little acorns grow, and with that sentiment in mind, we look at this unassuming, yet very popular symbol – the acorn.

Found as a charm on fob chains and bracelets, the acorn is often seen an ancillary motif in jewellery, balancing other symbols or complimenting a mourning sentiment, but more rarely being the prominent, singular motif used for a piece.

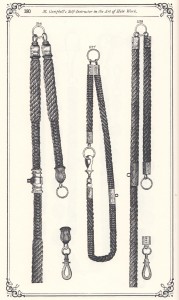

From its fitting, we can approximate it to Mark Campbell’s Art of Hair Working (1875) f.256, which shows the undulating pattern to the the charm clasp and the Rococo Revival pattern. Note that the style of the fitting is fundamentally important to identification in these fob chains. An incorrect assumption could throw out the date of a chain by over thirty years, and in an era of very heavy standardisation, this could change the purpose and perception of the jewel.

The eight-square chain braid is another factor in the quality and how its construction is important in hairwork and as a token of affection:

“TAKE sixteen stands, eighty hairs in a strand, and place them on a table like pattern. Commence at A: take Nos. 1 strands, lift across the table and lay down inside of Nos. 1 at B, and bring back Nos. 2 from B to A; then lift Nos. 3 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 3 from B to A; then lift Nos. 4 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 4 from B to A; then commence at Nos. 1 again, and repeat until the chain is completed.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire, and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire on to the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end to keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

There is a rhythmic complexity in the braiding of the chain and quite a lot of hair used shows how the effort of the love token not only aids its strength in construction, but the thought of the sentiment that the wearer would represent for their loved one.

Certainly, this is a chain that has endured the test of time. One of the disappointing factors of the chain is that there were few areas for personal dedications and inscriptions, unless there were charms attached. While the hair lives on, the personal statement is lost.