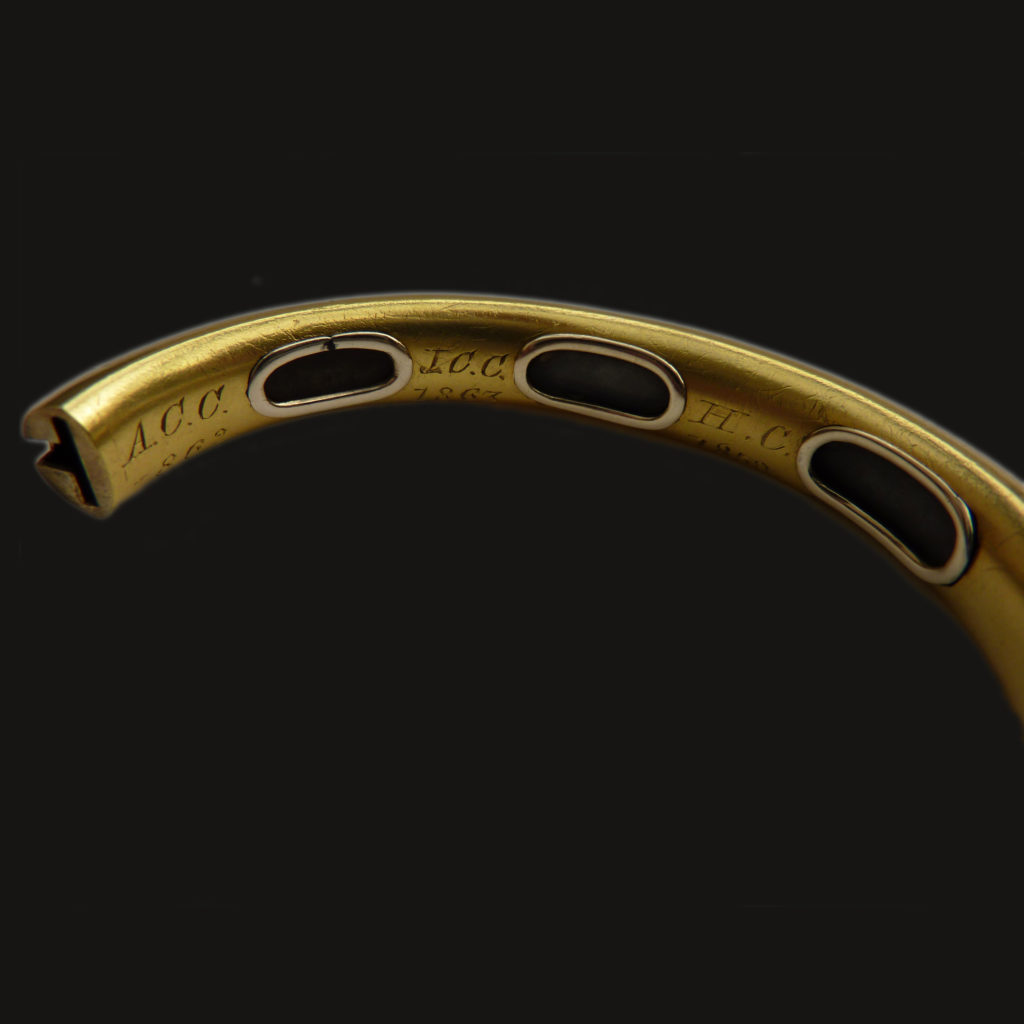

Victorian Enamel and Hairwork Bracelet

There is an unusual amount of fine construction in this bracelet that sets it apart from more common pieces in its clasp and enamel work. The fine weave of the hair is a tribute to its manufacture as well. Using white and blue enamel and featuring a hinged (and marked) clasp, this piece show fine 19th century Rococo revival scroll-work and is a fine piece for its time.

Flower symbolism conveys messages that are engrained within our culture, through the last two centuries of re-enforcing their statement as symbols. The 18th and 19th centuries Romantic movement helped establish a push away from the paradigms of ecclesiastical and traditional worship, while putting the focus back upon the natural world around and the passions of the human experience. Hence it is only natural (pun intended) that as the 19th century absorbed much of the cultural shift back to traditional values during the Gothic Revival period, that many of these concepts would remain and be elaborated upon, but not revolutionised. What do I mean by this? Simply that the interpretation of flora into symbolism was aesthetically pleasing, symbolically safe (often with roots back to religious concepts) and were easy to interpret in jewellery design. The motifs worked well within the Christian concepts and symbols, so where many other symbols may cause the viewer to think twice, flora was defined and catalogued for easy interpretation and use.

“Forget-me-not, O Lord!” is what a poor German knight shouted as he fell into a river. He and his lady were picking flowers by the side of the river at the time, no doubt enjoying the beautiful day around them, and yet as fate would have it, the knight’s armour dragged him down to the bottom as he fell in. Upon his cries to the Lord, he threw the blue posy of flowers to his loved one and promptly drowned. This little tale reportedly dates to around the 15th century, but no doubt had different permeations along the way, as romantic stories often do. Hence, the concept of remembrance, eternal love and faithfulness grow from this.

Another fable is that of the baby Jesus playing magician with his mother Mary. He was quite an articulate lad and thought how wonderful it would be if everyone could see her beautiful eyes forever. He touched her eyes and waved his hands over the ground below and then the magnificent blue forget-me-nots sprung from the earth. Relating back to my earlier points of how floral symbolism was safe in the context of religion, here we have the eternal memory symbolism not only implied with its name, but infused with solid Christian concept.

Now that we have the tales out of the way, the symbolism of the forget-me-not is obviously implied within its name. It should also be noted that the flower grows quite ubiquitously in Europe, America and Asia. Its first use in English literature is reportedly from c.1532 and is otherwise named Myosotis (mouse’s ear). Interestingly enough is the rise of the flower’s popularity c.15-16th centuries. This is what we, as jewellery historians, need to understand. From this, we have the popularity of the posy ring and its use as a love token in jewellery. The posy (poesy, posie, posey) emerged at a time when modern society was developing through a shift back to the personal and emerging from the middle ages and its strict adherence to ecclesiastical living. Giving a ring with an inscription on the inside as a token of love was a profound statement, it showed that relationships were increasingly interpersonal and not decreed before god. It was between the couple. Hence, the forget-me-not was used as a decoration (often crude) in some of these rings to denote its message of love and remembrance.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the use of the forget-me-not didn’t change, however, it did blend in well with the Rococo and Baroque excess of design well enough that it could balance with other flowers and leaf motifs. By the time of the Neoclassical period, its use was relegated more towards being a footnote in memorial jewel depictions painted on ivory. During this time and the rise of hairwork weaves becoming mainstream and popular, the forget-me-not did become a symbol used to create floral depictions from hair.

The 19th century is when the forget-me-not truly found its place as a central motif. Many rings, bracelets, brooches and mourning/sentimental peripherals showcased the forget-me-not as a primary motif, often boldly displayed on enamel. Often, other symbols (buckle/belt/serpent/cross) would complement the forget-me-not, rather than it being a symbol used as a design flourish or in repartition. Where the flower was used in more decorative areas of jewellery was in the Rococo Revival period, especially the latter 19th century, and lasted into the 20th century with its reliance on its romantic roots. Its use in the 20th century became much softer; in the Edwardian period, the romantic movement adopted the symbol and applied it (often in enamel) to lockets and by the time of the First World War, its relation to the remembrance of soldiers (carried through by poetry) and into the Second World War was assured.

Today, the forget-me-not is still as resonant as it was one hundred years ago and you can still find it as a popular motif in jewellery to give to a loved one.