The Collector

A collector’s passion can be driven by the simplest things. There’s the sheer joy and thrill of finding an object that mystifies the inner self and demands the attention to spark an element of joy and makes one want to chase that thrill again and again. For others, there’s the need for accumulation and gathering to compete for the goal of having the most. For others, there’s the narrative of what the combination of what these things mean and how they all interlock.

Mourning and sentimental jewellery has a profound affect upon people. For some, there is the morbid aspect of shock and its affect on other people, as one accumulates the affectation of it. For others, there is the exceptional notion of love being the intrinsic element that makes us want to remember a loved one or stay within a moment that is lost to time. There’s also the clinical view of history, as these jewels are very much tied to the past, which makes the historian tie together the threads of time and provide a narrative which opens a door into history.

All of these elements are sparked by the fascination of love as a concept, be it empathy for the one who has gone before, the construction of the jewel or a need to go back in time.

In this collection from Barbara Robbins, there is a narrative of jewellery that ties together the modern period of human development through fashion. There are enough jewels here, which have been the exemplary designs for their time, to those which have been re-appropriated for their very token of love. Messages of love from a person to another are intrinsic to what a memorial jewel’s meaning is. The jewel is created as a totem to another person, so capturing that message within in important for a particular style in time.

Posey rings, such as the piece in this image, are the foundation of the message that would be developed in memorial and sentimental jewels. They are simple jewels, representing a way of passing on a message that is inherently personal. Having the inscription on the inside offers the wearer an element of mystery, in the same way a closed locket can maintain a personal message. They were not necessarily jewels of high value, but they were attainable to a burgeoning middle class that could afford basic elements of fashion.

Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written inside the posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content. Here, the relation of the ring to the popular literature is the key factor in understanding just how the posie’s relation to society. They were jewels that could be for the commoner, but also transient as a style of love token through society because of their simple statements.

From a design perspective, posie rings are very random in their styles. Without a popular and fluid fashion/art movement to adapt to and no major industry to produce the affectations of fashion throughout a multi-structured society, the designs are disparate and may contain popular elements or may be basic bands. This makes identification of the simple bands difficult, unless the language can be identified, but within a bracket of the 16th to early 18th centuries, elements can be identified within a set number of years.

In this example, the 18th century can be seen through several elements. The crystal that encompasses the bezel is colloquially known as ‘Stuart Crystal’, a reference to it being a popular element in jewels during the reign of the Stuart era in British history. The facet of the crystal reflected like that of a diamond, yet it was attainable, so the commonality made it accessible. It is in a rectangular format, which developed post c.1700 and remained until c.1760. The Baroque style, which was popular during the 17th century, carried through the 18th century, until it was replaced by the growing Rococo fashion, integrating organic designs into jewellery. Baroque’s dominance, in its straight lines and opulent flourishes of floral design elements made it a very strong and powerful style for its time. The message, seen in jewels that were bold, particularly in the memento mori style, were supposed to be dominant, as there was the element of ecclesiastical judgement that a person would eventually face. This judgement, which lingered across fashion and art, gave society a context of their mortality and established social and political governance. With the Rococo period, the humanist element started to integrate into jewels. This ring shows the Baroque style, but only in its shoulders, which are decorated with a subtle pattern. It would not have been a jewel of high value for its time, but an important one for an individual.

Turning the ring over, the rosette shape in the bezel and its diminutive size are qualities that grew common through the 18th century. By the c.1740s, this was typical in jewellery design, for both morning and sentimental jewels. It was reflected in other jewels, from fobs to pendants, but developed from the c.1680s. Most notably, the important factor is the inscription around the band, “This and the giver is thine forever”. A sentiment of this kind of personal love is so personal and dedicated, that its message and the hair under the bezel are only amplified by it.

“Fear God Love me” is what this ring states, but it also poses a larger question; is it a jewel of its time, or is it a marriage between two? The message itself is one of piety and love, one can almost imagine this ring being slid over the finger of a loved one as a token of remembrance. Yet, the band and the bezel are not consistent. Posey rings and the inscription inside the band eventually found their way to the outside of the band in the 18th century, becoming common in sentimental jewels, usually set in enamel. Interior inscriptions remained, but were consistent with cursive font design, which remains today in jewels with dedications of love. This ring shows the early cursive font that was typical of the 17th century, yet the bezel is clearly a product of the early 19th century.

Seed pearls, set in this way, with the rectangular compartment in the bezel for hair, was a common design element of the early 19th century (c.1810-1830), so this could have been appropriated for another time. This would be typical, as sentimental jewels have always been reused through their life cycle, by a singular family or by many. When a jewel has a neutral dedication of love, without a person being directly referenced, their popularity through history retains the message and gets used again and again.

Fob charms, chains and seals are all important elements to a lady or a gentleman’s daily fashion. These were the functional items that attached to the body and their sentiment would have been referenced in daily use. Their elements encompass the identity of the wearer, as the attachments weren’t seen as necessarily a ‘fashion’.

The fob chain is an important as it was functional and defined fashion. Indeed, men’s fashion could be discerned by the number of button holes that shown the provided the anchorage for the chain. This would denote the number of accessories attached to the chain, and hence, the wealth of its wearer by the number of accessories and how the tailoring of the costume could be defined around it.

“The way in which watches have been worn has changed ver the years and they are as much an indication of wealth today as they were in the sixteenth century. From the time of Henry VIII it was fashionable for a monarch to wear a watch as a pendant at waist level. A skilled watchmaker could even make the watch in the form of wring. In the seventeenth century Samuel Pepys reflected in his diary that how a watch was worn gave an indication of the wearer’s character. Since its invention the watch, with its chain and attachments, has been the most decorative item worn by a gentleman. From Georgian times the chain was worn diagonally with a bolero style of vest (later called a waistcoat). The chatelaine (an ornamental chain hanging from the waist to which ,keys, seals and similar objects were attached) was worn by both men and women at this time and the skills of jewellers and goldsmiths were lavished on it.” (Gentleman’s Dress Accessories, Eckerstein, Firkins, 1987)

Wearing chains is important for status as much as it was for function. Combining a charm with the chain relates it to being more personal for the wearer. This mourning seal is as fashionable as it was a token of sadness. For the Neoclassical period, Romanticism and death blurred a line between what was popular fashion and what was genuine grief. The inscription reads “Affection Survives the Tomb” and depicts the mourning figure in repose in front of the urn.

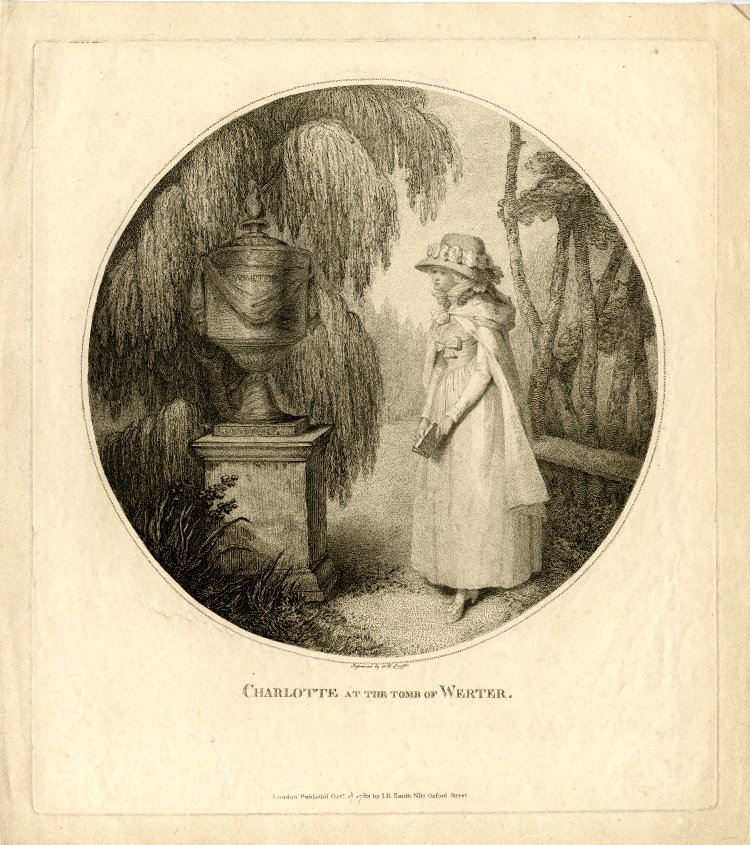

Popular culture was intrinsic to the rise of fashion and art in the 18th century. As previously seen in the Handel jewel, elements of mourning cross-pollinated from literature, music, art and fashion into jewellery design. In the above stoneware with blue jasper dip and applied white stoneware relief, the ‘tomb of Werther’ was based in popular culture. Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787 was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow and urn here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

For the c.1780-c.1820 period, sentimentality was based in popular culture in a more literal sense than previously seen. New wealth and the access to media influenced popular culture and could create jewels, such as the fob seen in here. It’s a difficult issue to put jewels like these into context; on one hand they are genuinely designed for the sake of being in mourning and remembrance, on the other, it was fashionable to wear the trappings of popular mourning symbols. For a daily item that would be a personal identifier, the wearer must have been quite vocal about their reason for carrying such an item.

Faith and hope are central themes in this ring, which encapsulates the Neoclassical period so perfectly. What is remarkable about this ring is that it is a construction of several mourning symbols as well as being a combination of personal grief elements. The ring is confident in its design style, which developed from the c.1760 period and the large swing towards Neoclassical symbolism. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought.

Two people died and the sentiment of this ring states “My Dear Friends Are Gone”. One passed away in 1775 and the other in 1781, making this ring based in the 1780s in terms of design. It shows, as the navette style, with its large north-to-south shape becomes the bezel and the shoulders show the dimpled indents that were typical of the time. By the 1790s, this navette shape became taller and the shoulders morphed more organically into the bezel.

Its symbolism is directly focused upon the mourning figure, who is the encapsulation of the human ideal, standing in the centre of the stage and holding the anchor. She is the heart of the emotion of the ring, and the anchor is faith and hope. A willow surrounds the border to her right shoulder and to her left, the broken branch of the tree represents a life cut short. The personal dedication of ‘my dear friends are gone’ is an interesting look into relationship status during the 1780s, as this isn’t for family, it’s for friends. The amplification of having a mourning jewel for friends transcends the family unit and becomes a fashionable thing to wear and display.

Some unusual styles have always taken fascination due to their sentimentality and oddity. The “lover’s eye” or ‘Georgian eye” is one such curiosity. Eye portraits are considered to have their genesis in the late 18th Century when the Prince of Wales (to become George IV) wanted to exchange a token of love with the Catholic widow (of Edward Weld who died 3 months into the marriage) Maria Fitzherbert. The court denounced the romance as unacceptable, though a court miniaturist developed the idea of painting the eye and the surrounding facial region as a way of keeping anonymity. The pair were married on December 15, 1785, but this was considered invalid by the Royal Marriages Act because it had not been approved by George III. Fitzherbert’s Catholic persuasion would have tainted any chance of approval. Maria’s eye portrait was worn by George under his lapel in a locket as a memento of her love. This was the catalyst that began the popularity of lover’s eyes. From its inception, the very nature of wearing the eye is a personal one and a statement of love by the wearer. Not having marks of identification, the wearer and the piece are intrinsically linked, rather than a jewellery item which can exist without the necessity of the wearer. Use of materials developed along with the size of the settings of eye miniatures, as pieces were surrounded by precious stones and became larger due to altering fashion. A good reference for the evolving trend of the shape of early 19th century jewellery can be seen in the Rings section, where settings and the shape of the mementos changed quite dramatically from 1790-1830.

The teardrop from the eye puts this particular jewel in the category of being for mourning purposes, but it doesn’t have the other embellishments of the black enamel or clear dedication. They were jewels meant to be anonymous, so giving an adequate answer is nebulous. Eye miniatures are the kind of cultural curiosity that has led future generations to copy the style, as it is the sentiment that means the most. Collectors have replicated many so perfectly that is is difficult to tell the provenance of a piece. This jewel is a wonderful example of its time and a benchmark for reference when viewing a good eye miniature.

By the early 19th century, the standardised symbols of Neoclassical mourning had set into the popular lexicon. They were popular in fashion, art and literature, to the point where they were understood without consideration of recognition.

In this excellent miniature, the design is perfectly laid out, with confidence in its construction. From the top of the tomb, the spirit of the child is breaking free and flying to the heavens, where the female mourner, perfectly reclined in her Neoclassical costume, acknowledges the child. The heavens are painted in soft blue and white, clearly articulating the sky and its serene nature. Cypress trees point to the heavens and the background scenario of other tombs is an unusual addition to the jewel. Compare this to the 1780s depiction in the ring and the maturity of the design is apparent. The tomb is designed in high-relief ivory and gold, with seed pearl articulation. Even the broken pieces of the tomb to the feet of the mourning lady are designed so pristinely that there’s no mistaking how direct the artist intended the piece. From this, we can see the development of art and design through the 18th to the 19th centuries.

Leading to this last piece from the collection, the clarity of the message and the reason for the jewel’s place is society is outlined. Black enamel, Gothic lettering, dominant acanthus and floral interior design and pearl surround set this jewel out in start contrast to itself. The black and the white point from the outside in direct the eye to the flower in the centre, which the border decries ‘CUT DOWN LIKE A FLOWER’. The Gothic Revival period was not known for its subtlety, which is why its message of either being in mourning or eventual death was powerfully used to reign in a growing and changing society.

In the 1820s, many influences upon society offered greater cultural flexibility within the social structure. The excesses of George IV and his investment in the arts bought new influences into the United Kingdom. From the death of Princess Charlotte who died in 1817, mortality was absorbed as a cross-cultural, kingdom-wide event, imposing values of the affectations of mourning on people which would resonate for the remaining 19th century. The values that were appropriated to show this in fashion led to the Gothic Revival being the identifier for grief and virtue, due to its return to religious values and simplicity that takes that pomp away from the fact of death.

The Gothic Revival period of the early 19th century is an extremely pronounced period of obvious consequences in art and architecture, but also heavily affecting in morality and cultural lifestyle. It is a period that overlapped other forms of mainstream style to eventually become the dominant visual presence, particularly in memorial jewellery and had left its mark for the greater part of the 19th century.

Firstly, we must look at this emerging style to conflict directly with the ideals of the Neoclassical period. Though the Neo-Gothic movement had begun c.1740, it took around sixty years for it to reach mainstream thought, a time when Neoclassicism was at its height.

Much of this thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

What can be gathered from a collection like this? There’s an intentional connection of historical threads that have led to the development of mourning symbolism. There is also a combination of beautiful jewels, which have a story to tell on their own. On top of this, there’s the excess of gathering them all in one place, which is commendable for anything outside of a museum. What it does denote is a pure focus on the element of love, which is either from the person who loves them at their time in history, as they will simply pass into another’s hands one day, as well as the love for the people who they were made for. Collecting lives and their messages is a lifetime affair and, if you have made it to the end of this article, you have shared the lives and discovered the development of how that was represented in modern history.