The Art of Hair Collection

The Art of Hair was originally a series of articles written in 2012 as the format of Art of Mourning developed. This collected edition features some edits as well as having the opportunity to have all the text in one location for reference and for those who are discovering how hair was woven, why it was such a popular material and how it was utilised in jewellery with symbolism. Please enjoy The Art of Hair:

Art of Hair 1: Victorian Hair Fob Chain With Serpent Clasp

Discovery is one of the most enlightening and exciting elements to collecting and understanding anything antique. With jewels, there is no limit to what data and learning we can extrapolate from their construction, their design, their materials and how that brings us one step closer to a time long forgotten.

One of the more overlooked elements in jewellery, and as a material in general, is hair work. Hair art holds a fascination with some and a the macabre with others; the irony being that the majority of woven hair jewels produced were for sentimental reasons and not mourning.

It was a material that could be worked to become as fine as silk or as strong as any rope, a durable keepsake for a loved one that could be presented as a fine jewel or worn as a daily accessory. This is why hair work needs to be understood in a greater capacity by not only us, but by those around you.

So, let’s begin in the most humble of places. Let’s look to this 19th century fob chain and learn how it was made, as well as how to spot the jewel and put it to a year that will fit right into your collection! For this, we will acquire the help of Mark Campbell and the brilliant ‘The Art of Hair Work’ (1875) to help us along the way.

The first thing to look at with fob chain, ring, necklace, bracelet or any other form of hair working jewel are the fittings that surround it. There is so much to be extrapolated from the style; it could be Gothic Revival, Rococo Revival, Etruscan or any other form at the time; these are the elements that at least will put the jewel in the era that you can define it.

What is the first element we can see on this clasp? Certainly, it has to be the serpent! This symbol is an ancient one and if you’re a collector of the mourning and sentimental, chances are you’ve seen it in jewellery going back to the 17th century. The serpent can be found swallowing their own tail, which represents eternity, often to ‘love another for eternity’ (if the piece is dedicated to someone or from someone), also rebirth and immortality.

Powerful statements of love and powerful statements for the self.

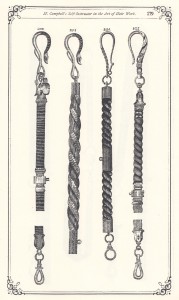

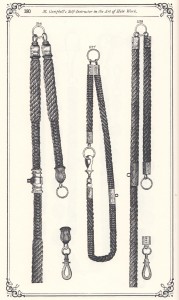

Let’s now look to Mark Campbell’s catalogue for the fitting type and we can see a remarkable similarity with styles that were popular at the time. Obviously, the serpent is the most prevalent, yet we have the twist, seen in f.255 with the could around the base of the clasp and the tighter coil that relates to f.254. Yet the head of the serpent is much like f.252/3 in that it should the actual serpent winding up the clasp itself. This is a standardised style, a style that had been engrained with the mainstream fashion, no doubt with any help from Queen Victoria, who had a keen affection for the sentiment.

Following this, the braid comes into examination. From here, it’s best to look to Campbell as the entwining details are in the construction:

“Double Rib Chain Braid.

TAKE twenty-six strands, sixty hairs in a strand, and place them on a table like pattern. Commence at A and B: Take Nos. 1 and change places by swinging them around the table to the left; then take the third strands to the right of A and B, and change places by swinging them around the table to the righto then take the fourth strands to the right of the ones last taken, and change places by swinging them around the table to the left, and so on, working around the table to the right; first swinging the strands to the left, and then to the right, taking alternatively the third and fourth strands to the right of the ones last used, until the braid is finished.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire , and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire to the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end of keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

And here we have the methodology of the hair work itself. We have an understanding of its construction and why it would be used as a chain, with enough elasticity to hold heavy objects; such as a pocket watch or male accessory. Always look to the hair work in your jewel to identify it; Campbell gives some wonderful insights into the advancement of hair work, as well as the era of their respective constructions.

Art of Hair 2: Directions for New Beginners

Hairworking, as a practice, was something that could be done in the home or in a proper profession. Indeed, it was one of the earliest, early-modern, female professions within an industry, as women would be employed to weave hair. Mark Campbell’s excellent ‘The Art of Hair Work’ (1875);

“THE hair to be used in braiding should be combed perfectly straight, and tied with a sting at the roots, to prevent wasting. Then count the number of hairs for a strand, and pull it out from the tips, dip it in water, and draw it between the thumb and finger to make it lie smoothly. Then tie a solid single knot at one end, the same as you would with a sewing thread.”

The methodology of hair art is in its simplicity as a keepsake. This is a token of love that could be given to a person of affection with a simple lock of hair. Where Campbell’s instructional guide justifies the use of hair as a legitimate material for jewellery production is in how it provides a balance between this and technicality. Campbell writes in a way that makes hair working incredibly simple for the beginner; as long as one has the instruments for its construction.

There is also an assumption based upon the weaving style that there are various difficulties in the more elaborate patterns of hair working.

Campbell goes on to describe the bobbin next. The bobbins cut defines the braiding pattern from fine open work, to tight braiding. No. 1 can be used from one to four hairs in a strand, while No. 2 is for five to twenty.

Following on from the change in complexity of hair work, the use of the bobbins suggests the differentiation of the difficult to the simple. Certainly, one must have skill to weave the difficult and more elaborate styles of multiple strands of hair, whereas one who could work in two to four hairs could weave simpler patterns of hair.

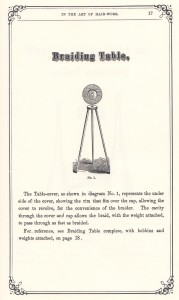

The essential element here is the table. The tripod table has a cap and a rim, which revolves. There is a hole through which the braid and weight can be passed through.

Here is the most important piece of the hair working instrumentality. This table is the centre of the hair working method; defining the outcome and providing the basis of the professional hair working industry. With this table, the amateur hair worker could accomplish the designs that could be done within the profession of hair work.

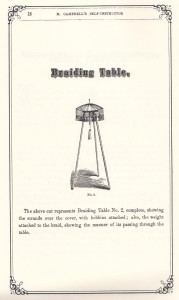

In this image, we can see the strands of hair over the cover with the bobbins attached and the weight attached to the braid. This enhances the weight of the hair to be passed downwards and braided into the desired shape.

These lead bobbins are for braiding rings and chains from two to forty hairs. The smaller, No 1. is used for a few strands of hair, while No 2. is for higher numbers, due to its size. Most interesting is the need to;

“prepare the bobbin, wind it with thread, as shown in the cut, leaving the thread some three inches long with a solid knot tied at the end”

Certainly, the hair worker’s craft was a delicate one; a craft which required (and still does) patience. A patience that can acknowledges the reason for importing great quantities of colour-matched hair for use in the industry. This is the reason for many sentimental jewels having greater amounts of hair than what was given to the jeweller for usage in a jewel and also for the maintaining of a proper industry that could turn over high numbers within a short period of time.

The lead weight was the counter balance to the hair working operations. It could ‘draw the world through the centre of the table as fast as braided, and to balance the bobbins’, which would essentially change the braid from being loose, light or rough. Weights could be added as desired.

Such was the profession of the hair working industry in London, that advertisements of competing hair workers were common. This alludes to any contemporary fashion rivalry in the media and gives us a great insight as to Campbell’s demystification of hair weaving in the 1870s:

“Hair jewellery, Artist in Hair. Dewdney begs to inform Ladies or Gentlemen that he beautifully makes, and elegantly mounts in gold, Hair Bracelets, Chains, Brooches, Rings, Pins, Studs, etc. and forwards the same, at about one-half the usual charge. A beautiful collection of specimens handsomely mounted kept for inspection. An illustrated book sent free. Dewdney, 172 Fenchurch St. London.” (Advertisement, Illustrated London News, May 1862).

These are the forms for braiding over, which would define tight to open weave braids. For collectors, you may find hairwork jewels with the form showing out from frayed hair. This happens most of all around the clasp and the fittings; you will often find the interior being exposed to these jewels and accessories. It doesn’t make a great deal of impact to their sentimental value, but from a collecting standpoint, these jewels are not repairable in a way which wouldn’t compromise their original construction.

Be sure that your hair work is protected and kept out of the light and moisture. Discolouration of hair, as well as the very susceptible nature of hair to grow mould are very common within antique hair work worn today. Bacteria grows within the weave strands quite easily and can spread to other jewels if stored together, so do be careful if you choose to wear your jewel. Many of the style were worn over clothing, as opposed to against the skin, which can equate to why mistakes have been made today (as necklaces are more commonly worn under the clothing) and treatment of the hair isn’t proof that it won’t contract any mould.

And it is the weave that defines. As seen in the previous article, there is a great correlation towards how we can identify a jewel. Often, many have been appropriated for other reasons, the most common of which being a fob chain turned into a necklace.

Bracelets have much more different and open weaves, so they are easier to spot. Elasticity is important for stretching over a wrist (more important in the latter 19th century due to fashion), but it is necessary to analyse the jewel to be sure of its intent.

The most obvious things to look out for are the fittings. If there are obvious fittings in the centre for a fob chain, then it most certainly wasn’t originally a necklace, but a jewel can be worn for many purposes, so that is the prerogative of the wearer.

Art of Hair 3: Victorian Hair Fob Chain With Locket

Charms and accessories on hair fob chains and necklaces are as bespoke to the piece as the hair itself. It is important for the collector to understand that these are the elements of daily fashion that a gentleman or lady (depending on the accessory) could adorn themselves with to remind them of their loved one. One element here to demystify is that they were used predominantly for mourning purposes and this couldn’t be further from the truth. As we have seen with hair as a material, this was fashionable and a way to show ones love and still keep that functional.

The design of the centre clasp is one of the more important features to focus upon when we look at this particular fob chain. Here, we look to Mark Campbell’s Art of Hair Work to match it close enough to approximate its date and how it was integrated into the chain.

Looking at the page, you can see the similar elements to f.265; yet this chain fitting tapers within the centre and has the loop for charm attachment. There is also the random floral design flourish to the edge of the chain’s fitting that carries through the elements also seen on the locket charm itself.

This is a motif that can be traced to the 1810s, when there was experimentation of the floral Rococo elements in jewels, particularly flanking the bold, Gothic Revival styles, but it survived and maintained in sentimental jewellery throughout the 19th century and many of these elements are still popular in jewels and symbolism today. Note the two forget-me-nots within the design of the locket, which is an important symbol to match with the hair work itself:

Flower symbolism conveys messages that are engrained within our culture, through the last two centuries of re-enforcing their statement as symbols. The 18th and 19th centuries Romantic movement helped establish a push away from the paradigms of ecclesiastical and traditional worship, while putting the focus back upon the natural world around and the passions of the human experience. Hence it is only natural that as the 19th century absorbed much of the cultural shift back to traditional values during the Gothic Revival period, that many of these concepts would remain and be elaborated upon, but not revolutionised. What do I mean by this? Simply that the interpretation of flora into symbolism was aesthetically pleasing, symbolically safe (often with roots back to religious concepts) and were easy to interpret in jewellery design. The motifs worked well within the Christian concepts and symbols, so where many other symbols may cause the viewer to think twice, flora was defined and catalogued for easy interpretation and use.

“Forget-me-not, O Lord!” is what a poor German knight shouted as he fell into a river. He and his lady were picking flowers by the side of the river at the time, no doubt enjoying the beautiful day around them, and yet as fate would have it, the knight’s armour dragged him down to the bottom as he fell in. Upon his cries to the Lord, he threw the blue posy of flowers to his loved one and promptly drowned. This little tale reportedly dates to around the 15th century, but no doubt had different permeations along the way, as romantic stories often do. Hence, the concept of remembrance, eternal love and faithfulness grow from this.

Another fable is that of the baby Jesus playing magician with his mother Mary. He was quite an articulate lad and thought how wonderful it would be if everyone could see her beautiful eyes forever. He touched her eyes and waved his hands over the ground below and then the magnificent blue forget-me-nots sprung from the earth. Relating back to my earlier points of how floral symbolism was safe in the context of religion, here we have the eternal memory symbolism not only implied with its name, but infused with solid Christian concept.

Now that we have the tales out of the way, the symbolism of the forget-me-not is obviously implied within its name. It should also be noted that the flower grows quite ubiquitously in Europe, America and Asia. Its first use in English literature is reportedly from c.1532 and is otherwise named Myosotis (mouse’s ear). Interestingly enough is the rise of the flower’s popularity c.15-16th centuries. This is what we, as jewellery historians, need to understand. From this, we have the popularity of the posy ring and its use as a love token in jewellery. The posy (poesy, posie, posey) emerged at a time when modern society was developing through a shift back to the personal and emerging from the middle ages and its strict adherence to ecclesiastical living. Giving a ring with an inscription on the inside as a token of love was a profound statement, it showed that relationships were increasingly interpersonal and not decreed before god. It was between the couple. Hence, the forget-me-not was used as a decoration (often crude) in some of these rings to denote its message of love and remembrance.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the use of the forget-me-not didn’t change, however, it did blend in well with the Rococo and Baroque excess of design well enough that it could balance with other flowers and leaf motifs. By the time of the Neoclassical period, its use was relegated more towards being a footnote in memorial jewel depictions painted on ivory. During this time and the rise of hairwork weaves becoming mainstream and popular, the forget-me-not did become a symbol used to create floral depictions from hair.

The 19th century is when the forget-me-not truly found its place as a central motif. Many rings, bracelets, brooches and mourning/sentimental peripherals showcased the forget-me-not as a primary motif, often boldly displayed on enamel. Often, other symbols (buckle/belt/serpent/cross) would complement the forget-me-not, rather than it being a symbol used as a design flourish or in repartition. Where the flower was used in more decorative areas of jewellery was in the Rococo Revival period, especially the latter 19th century, and lasted into the 20th century with its reliance on its romantic roots. Its use in the 20th century became much softer; in theEdwardian period, the romantic movement adopted the symbol and applied it (often in enamel) to lockets and by the time of the First World War, its relation to the remembrance of soldiers (carried through by poetry) and into the Second World War was assured.

“Take eighteen strands, eighty hairs in a strand, and place them on table like pattern. Commence at A and B: take Nos. 1, and swing around table to the right, and place the No. 1 from A. over the Nos. 2 and 3 at B, and the No. 1 from B over the Nos. 2 and 3 at A; then go to C and D, take the Nos. 1 and change the same; then go to E and F, and change the same; then go to B and A, and change as at first (all the time taking the Nos. 1 and swinging to the right, for when you lay them over the Nos. 2 and 3 it makes them Nos. 3 and makes Nos. 2 Nos. 1) and so on, until the chain is finished.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire, and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire on the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end to keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the numbers of hair in a strand.”

Note the process of setting the hair by boiling and baking it, then adding shellac. This is the most common aspect of hairworking that is necessary to set the shape. As to the twist chain style of this chain, it is one of the more common styles that you will find to many fob chains in varying degrees of condition. This is mostly due to the durability of the weave and the popularity of hair as a material.

Art of Hair 4: Victorian Hair Fob Chain With Acorn Charms

There are several elements here that are intrinsic to Victorian style and fashion that represent the person, that involves not only hairwork, but symbolism itself.

With this fob chain, a fashion accessory that was as essential to men’s fashion as would be the presentation of mourning (though this is a sentimental piece), there are pieces which combine to create a whole. There is the pearl, the garnet, the acorn and the hairwork, forming a union between symbolism and material that could be used as a part of daily fashion. But why was it constructed, how was it constructed and why was it worn?

Let’s first look to the fittings, the first thing that a collector should be analysing. Here, we have signs of wealth, due to the use of the pearl and garnets, as well as the bespoke charms. It should be noted that this is requested by the person who bought the piece, as each element could be chosen from the catalogue to assemble the desired combination of sentimentality for the chain. A gentleman’s accessory was built around the fob chain, as this housed many of the essential elements for daily use, such as the pocket watch, hence the use of hairwork is the primary element that draws this back to sentimentality and its purpose in late Victorian culture.

WIth higher catalysts for change in fashion during the 18th and early 19th centuries, the latter 19th century had a very fixed view of mainstream fashion, with many underlying and peripheral art movements growing in their own right. Yet, just because movements happen over a period of time (such as the Arts and Crafts movement), this does not mean there is a clear change in fashion over a short period due to a single event. Generations grew up with the paradigm of fashion (royalty) dictating the nature of fashion and with Queen Victoria remaining in mourning from 1861, we have expansion of an Empire at an exponential rate, but only elements of this showing through within the culture. This is within the areas annexed and bought into the British Empire that could influence the culture (such as India); everything from food and fashion was affected by this. Though there was bleed-though from to the tastes of the aristocracy, it did not affect the proper nature of what could be worn at court or presented as the fungible way in which a person presented themselves in a passionate way, be it mourning or sentimentality.

Hence, this is why such a simple fob chain can be seen as a culturally important element of daily life for its time. This is how a gentleman would be presented and the smaller pieces to this fob chain reflect that persona.

The fob chain is an important as it was functional and defined fashion. Indeed, men’s fashion could be discerned by the number of button holes that shown the provided the anchorage for the chain. This would denote the number of accessories attached to the chain, and hence, the wealth of its wearer by the number of accessories and how the tailoring of the costume could be defined around it.

“The way in which watches have been worn has changed ver the years and they are as much an indication of wealth today as they were in the sixteenth century. From the time of Henry VIII it was fashionable for a monarch to wear a watch as a pendant at waist level. A skilled watchmaker could even make the watch in the form of wring. In the seventeenth century Samuel Pepys reflected in his diary that how a watch was worn gave an indication of the wearer’s character. Since its invention the watch, with its chain and attachments, has been the most decorative item worn by a gentleman. From Georgian times the chain was worn diagonally with a bolero style of vest (later called a waistcoat). The chatelaine (an ornamental chain hanging from the waist to which ,keys, seals and similar objects were attached) was worn by both men and women at this time and the skills of jewellers and goldsmiths were lavished on it.” (Gentleman’s Dress Accessories, Eckerstein, Firkins, 1987)

So, now let’s look to the acorn motif and let it reveal itself upon the gentleman.

Great oaks from little acorns grow, and with that sentiment in mind, we look at this unassuming, yet very popular symbol – the acorn.

Found as a charm on fob chains and bracelets, the acorn is often seen an ancillary motif in jewellery, balancing other symbols or complimenting a mourning sentiment, but more rarely being the prominent, singular motif used for a piece.

Often seen on military tombs, the acorn can stand for power, authority or victory, however it is also a statement of longevity, strong new growth and new life.

From its fitting, we can approximate it to Mark Campbell’s Art of Hair Working (1875) f.256, which shows the undulating pattern to the the charm clasp and the Rococo Revival pattern. Note that the style of the fitting is fundamentally important to identification in these fob chains. An incorrect assumption could throw out the date of a chain by over thirty years, and in an era of very heavy standardisation, this could change the purpose and perception of the jewel.

The eight-square chain braid is another factor in the quality and how its construction is important in hairwork and as a token of affection:

“TAKE sixteen stands, eighty hairs in a strand, and place them on a table like pattern. Commence at A: take Nos. 1 strands, lift across the table and lay down inside of Nos. 1 at B, and bring back Nos. 2 from B to A; then lift Nos. 3 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 3 from B to A; then lift Nos. 4 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 4 from B to A; then commence at Nos. 1 again, and repeat until the chain is completed.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire, and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire on to the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end to keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

There is a rhythmic complexity in the braiding of the chain and quite a lot of hair used shows how the effort of the love token not only aids its strength in construction, but the thought of the sentiment that the wearer would represent for their loved one.

Certainly, this is a chain that has endured the test of time. One of the disappointing factors of the chain is that there were few areas for personal dedications and inscriptions, unless there were charms attached. While the hair lives on, the personal statement is lost.

Art of Hair 5: Victorian Hair Fob Chain With Black Enamel Fittings

Symbolism in watch chains and their fittings are primarily the key identifier when it comes to many of the surviving chains today. The identification can lead us to note the quality of the piece and its value.

From catalogues of the 1860s to the end of the century, each element within a preview of the desired piece could be mixed at matched to its fittings. These fittings could be chosen by the person who commissioned the chain to personalise it with their desired sentiment.

As these fittings ranged in quality, from pinchbeck and lower grade alloys, to higher gold content, this is what we have to take into account for how this piece could have been worn within its social level.

From this, we look to the hairwork and see just how incredible and detailed the weave is, and also to note is the colour. Predominately, brown is the most typical of hair found commonly today, followed by darker tones, while blonde or red are on the other end of the scale.

This very charming piece has blonde hair, gold fittings (with a good deal of weight), inlaid

enamel acorn motifs and the wonderful buckle to the loop itself. As we know, the acorn motif was found as a charm on fob chains and bracelets, the acorn is often seen an ancillary motif in jewellery, balancing other symbols or complimenting a mourning sentiment, but more rarely being the prominent, singular motif used for a piece.

Often seen on military tombs, the acorn can stand for power, authority or victory, however it is also a statement of longevity, strong new growth and new life.

The cable twisted chain braid has a secondary loop around the main cable of hairwork, giving the piece an extra dimension and really showing off just how the level of delicacy over simpler weaves resonated with the fashion of how it was worn. Certainly, this piece is as decorative as it is function. As noted by Godey’s A Series of Papers on The Hair (1855): “Among the many curious occupations of the metropolis of London, is that of the human hair merchant. Of these there are several, and they import between them more than fifty tons of hair annually.” Colour matching the hair was as important as the weave itself, ensuring ease of construction for the hair weaver and that the client gets a product back which reflects the hair given to the weaver. This blonde piece is remarkable in that it still retains its original lustre and softness.

“TAKE sixteen strands, eighty hairs in a strand, and place them on the table like pattern. Commence at A and B, take No. 1 at A in righthand and No. 1 at B in left hand, and swing them around to the left and change places with them ; then take successively Nos. 3, 5, 2, 4, 6, 3, 5, 7, 4, G, 8, and change the same; then commence as at first with No. 1, so on repeating until the braid is finished.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire and push the braid together on the wire; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry then take it out and slip it oft’ of the wire on to the cord, and sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end to keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

Finally, let’s look at the belt/buckle/garter motif. The closest in Mark Campbell’s ‘Art of Hair Work’ matches with these styles, yet uses its motif in the loop well:

Often a symbol can be so ubiquitous that it disappears from sight. It’s commonly used, often present with other symbols and it’s just accepted that it’s there.

Let’s turn those ideas around on themselves and clasp together the meaning of the belt/buckle in jewellery symbolism. If you’re a collector of mourning and sentimental jewels, there’s a good chance you’ve got several pieces with this symbol on it, be it a bracelet, ring, locket – the buckle can be seen in just about every form of jewellery. This is a symbol that became popular in the 19th century and its meaning is actually quite simple.

The simple answer is that the belt/buckle is much like the serpent, it represents eternity, fidelity/loyalty, strength and protection. As the symbol curves around and threads back into itself, creating an eternal loop, it threads through the buckle and tightly overlaps itself.

As an object of use, the belt dates to the prehistoric, basically as necessity dictates the use of a way to either hold up any clothing below the waist or fasten objects to the waistline for ease of access. This could be as practical as holding up a pair of pants or as precious as holding a ceremonial/ ecclesiastical object for decoration. The device is a perfect marriage of form and function. And to accompany this, as long as humans have been mining metals, at least recorded to the Iron Age, the buckle has accompanied the belt to hold fast to the waist.

From a high level perspective, the belt and buckle split the body in two, creating a clear delineation through the waist from the northern and southern halves of the body, but also holding the body together through this middle separation through its interconnecting and tight nature. As we move on, you’ll see how this relates to its context with other symbols.

Essentially, the buckle/belt motif relates back to this unbreakable strength of upholding loyalty and in turn, memory forever. Its eternal loop is combined by its strength with which it holds up the virtue that it contains. When related back to the family as a unit, a loved one who is lost would ordinarily break down the family and cause untold grief and sadness, however, the presentation of this symbol from a loved one as representation of the person who has passed on only intensifies the eternal strength and love for the person, as well as the strength of the family to stay together. This symbol also relates to love tokens, for this eternal loving strength can obviously be applied to the living; it is a symbol that is all encompassing. So, while many rings and bracelets took on the shape of the buckle in the 19th century, they don’t necessarily denote mourning or death.

There is where we have to look at the symbol when it is combined with other symbols to discover its nature in relation to the piece. Look at this particular piece with the upside-down torch. Note how the buckle is not only a decorative border, but it is in fact wrapping itself around the life cut short and strengthening this with an eternal loop that forever holds tight. This is important, as the love and gravity of the symbol are enhanced by the buckle.

When the buckle is worn as a complete motif, as it becomes the ring in this case, think of how it is worn. This buckle is tight around the finger, the sentiment of love becomes part of the body, in effect, creating that bond of eternal love around the very person. The person becomes the symbol.

Late 19th century rings are wonderful showcases for the depiction of the buckle – be it mourning or sentimental token.

Different constructions involving hinged buckles that open to reveal hair or enclosed hair with letters of a person’s name or dedication sentiment would be placed in panels over the hair itself, all creating the belt/buckle motif.

It should be noted that you can find the belt/buckle motif on rings as secondary symbols in enamel, not just making the band itself. As it was a multi-purpose symbol, you can also find them in silver and other materials quite commonly from the latter 19th century into the 20th. For many sentimental jewels, the garter as a symbol does infringe upon the buckle symbol from time to time, in those particular cases, it becomes a symbol of chastity and virtue.

Moving back into the idea of the belt/buckle in context with other symbols, this particular piece shows the buckle with the ‘In Memory Of’ sentiment. This once again reflects the eternal strength of memory and in this case, the dedication itself becomes the symbol, which has become enhanced by the belt/buckle. This is quite common from the mid 19th century on, the rise of the belt/buckle had become part of the cultural lexicon.

In the case of this bracelet, you can see how its decoration once again turns the wearer into the symbol of strong affection and love. Wrapped around the wrist, it promotes a strong connection of the wearer to the person who commissioned it.

As with all these symbols, loyalty and fidelity relates to the tightness of the eternal love motif that the wearer promotes through their keepsake.

And there we have it. From the simplest of accessories, and one of the most common, we have taken a look at how hair was braided, the industry from which it came, the fashion which made it necessary and the Victorian view on love and sentimentality.