Sentimental Hair Art

“Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look to to Heaven and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say: ‘I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now.’

Godley’s Lady’s Book, 1860

Hair is a transcendent material. It has the ability to capture all the essence of a loved one, the colour to the very smell, and be able to transform into a piece of art. Sentimentality in fashion comes at a cost. Be it a dress that could be created or customised to be in mourning through to a jewel that could made for love, there’s no finer material for the loving keepsake. It literally is a piece of the loved one, without any elaboration to extend its value.

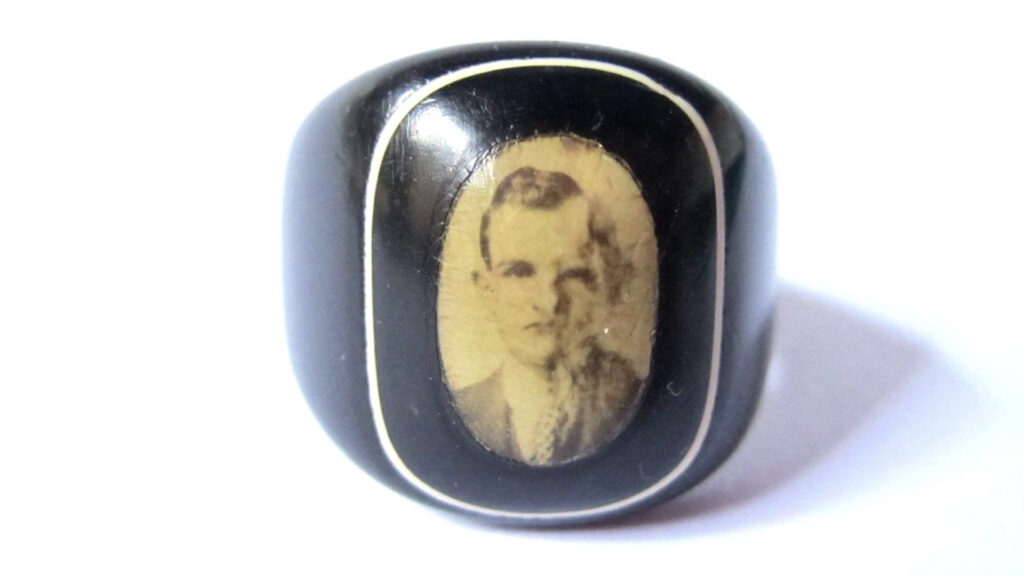

As it was a simple to use material, its adaption to jewellery and art exist from the household to the professional. In the scenario depicted in this hair art piece, there is all the trappings of love on display, with no element being unused for the unconditional message of love and sentimentality.

Cultures were highly mobile in the mid 19th century, much more so than any other time in history. From rail to faster shipping, taking a piece of oneself to another country and relocate was more attainable for those not expelled through persecution or wealth. Taking a piece of that culture to another land was essential to identity, and mourning is one of the primary identifiers of what makes an individual have a set of cultural values. Be it through religion and what the consideration is after death, to how one would appear in mourning, fashion in death displays what one’s value system is. With the changing borders of the 19th century into the 20th, having a ubiquitous representation of death that allowed itself to be free from religious value required the style to be an amalgamation of what had come before.

What is most remarkable is that these hair art pieces are similar in Switzerland, England, France, Prussia, America and Australia. the symbolism of mourning was becoming standardised and what was seen was what was cemented cross-culturally. These French pieces are beautifully produced, but could be transported across continents and still identified as mourning symbolism.

Hair and Art

Prisoners of the Napoleonic War in the early 1800s resided in Tunbridge Wells, Kent and bought with them skills and knowledge of hair working. Their skills were influential to the growth of the hair working industry, as the focus was applying the material to weaving in jewellery.

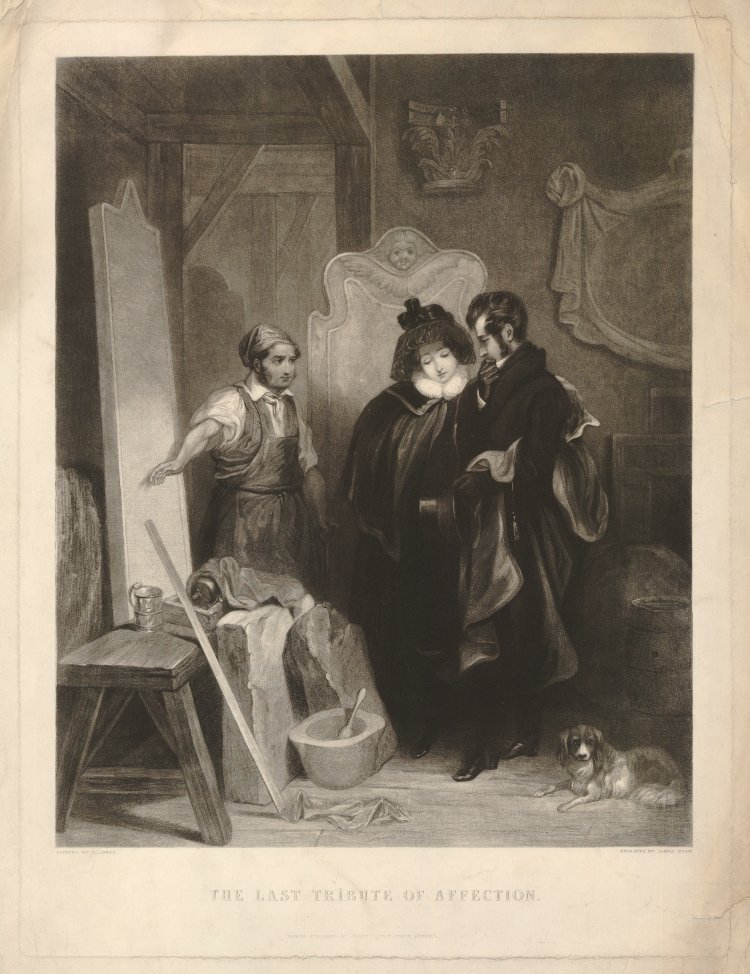

William Holford and Charles Young founded a firm based in Clerkenwell based around the creation of hair work jewels and art. In their 1864 book titled Jewellers Book of Patterns of Hair Work, they displayed the designs which can be seen in the works of art that are the subject of today’s article. Willow trees, memento mori skulls, scythes, anchors, hearts, padlocks, yews and graveyards show the variation of the mid 19th century, which had taken the history of mourning symbolism and standardised its essential iconography to be what we identify today. Note the change from the early 18th century and its memento mori influence of clear identifiers of death and decay for mourning (the skull, skeleton, hourglass) to the Neoclassical, which had done away with much of this, to display idyllic settings of love and Greco-Roman sentimentality.

The urn, willow and mourning female had replaced the skeleton and the finality/judgement of death. By the 19th century, much of these symbols relate to how culture and technology covered a wider reach of culture. Mass transit, international communications and technologies led to mass production, leaving lesser degrees of cultural identity in death. What was fashionable in England or France would be fashionable in Australia or America, as these symbols were identifiable. More influence came back upon religion or country, which defines culture in communities that were populating highly through colonisation and emigration. Major waves of art styles to promote change became led by the wealthy, rather than permeate through the culture from the ground-up or simply be led by a monarch, hence mourning standardisation became set in its Western identity. What we see in the hair art produced in todays pieces reference this. The literal depiction of the grave, urn and willow were the most popular symbols of the Neoclassical period of the 18th century, so its adaption into hair art in the mid 19th century is simple. There’s no challenge to personal identity through it; it simply exists to show a non denominational scenario of mourning.

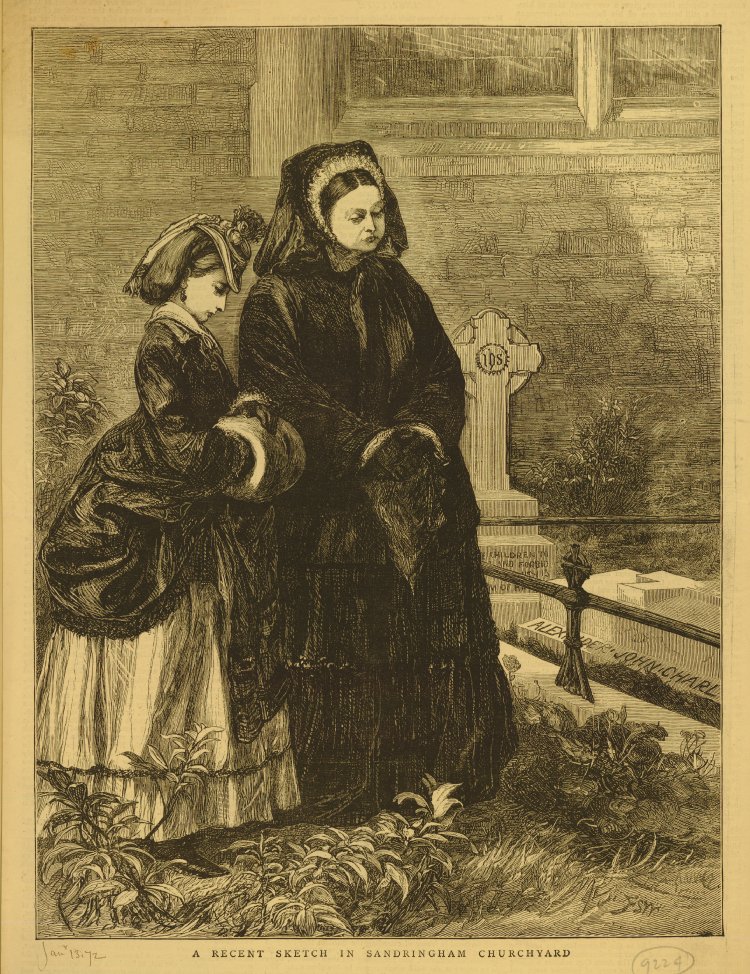

In the Paris Exhibition of 1855, a life-size portrait of Queen Victoria was created, a worthwhile homage to a queen who appreciated the sentiment of hairwork so much. Indeed, with such a cultural importance on the value of hair as a material, the French were the epitome of style and to use such a material in a gesture shows just how widespread hair was used in mainstream fashion. In 1858, fashion magazine La Belle Assemblè referred to the French hairwork artist Limmonièr in a revolutionary light. La Belle Assemblè expands on the association with hairwork as a sentimental device and identifies it as a jewellery construction material in its own right, not simply “in which some beloved tress or precious curl is entwined”.

“(Old styles) gave the appearance of having been designed from a ‘mortuary tablet’. Have we not all met ladies wearing as a brooch, by way of loving remembrance, a tomb between two willow trees formed of the hair of the individual from whom their crepe was worn, and which from its very nature must be laid aside with it? But the new hair jewelry made by Limmonièr is an ornament for all times and places. He expands it into a broad ribbon as a bracelet and fastens it with a forget-me-not in turquoise and brilliants; weaves it into chains for the neck, the flacon, or the fan; makes it into a medallion, or leaves and flowers; and of these last the most beautiful specimens I have seen have been formed of the saintly white hair of age. This he converts into orange flowers, white roses, chrysanthemum and most charming of all, clusters of lily-of-the-valley.”

La Belle Assemblè

La Belle Assemblè provides a very good advertising spiel for Limmonièr but also provides an insight into how the French perceived hairwork in 1858. By the latter half of the 19th century, hairwork was nearing a phase of unpopularity in France, though this article shows how hairwork was removed, or was attempted to be removed, from mourning and memorials. The article ridicules prior styles of hairwork, as being designed from a “mortuary tablet”, and the stale nature of the depictions of hairwork. By 1858, many of these symbols were not being heavily used in mainstream mourning jewellery, being widely used in the late 18th century / early 19th century with the popularity of neo-classical art. However, the point is made, that hairwork is a beautiful material when combined with Limmonièr’s artistry.

Mourning Fashion in the Mid 19th Century

Crepe was the primary material used in mourning fashion from the 19th century, being non-reflective and symbolic of the first stage of mourning under court mandate. Widows had to wait one year and six weeks, with the first six months in black wool. Lord Chamberlain and Earl Marshall both ordered shorter periods of mourning in France and England respectively. By the 1880s in Britain, twelve weeks of mourning were ordered by the death of a king or queen, six weeks after the death of a son or daughter of the sovereign, three weeks for the monarch’s brother or sister, two weeks for royal nephews, uncles, nieces or aunts and ten days for the first cousins of the royal family. Foreign sovereigns were mourned for three weeks and their relatives for a shorter time. Mourning was divided up into First, Second and Court mourning.

It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning: ‘the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crepe hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crepe fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crepe hatbands and black swords and buckles.’ For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear. Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this Industrial Revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels.

Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crepe gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act.

Wood engraving

Their decline came in 1886, with the 1880-82 period of fabric being ordered at 46,000 packets of fabric to 30,000 in 1892-94. This is a steep decline that relates to the end of the mourning industry and its fashion. The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways. Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

On the continent, however, much of the exports of Courtaulds’ sales were to France, as in 1899, more packets of crepe, known as ‘Crepe Anglais’, were sold than had been previously seen. Courtaulds offered a softer crepe, which was popular, rather than the stiffer fabrics, and was advertised as such. By 1921, ‘Latin Countries’ were the major exporter of crepe, which speaks to the change in dominating mourning styles from the ecclesiastical to the fashionable. Being in popular fashion, mourning was challenged; not something that was mandated as it had been, particularly through the period of the First World War and its high mortality. The pomp surrounding mourning reduced to be personal. Mourning and its stages weren’t enforced and not an indictment on the family, so what a person felt was more allowable to be presented within society for mourning ritual. As to the crepe and its exports, this was more popular in Catholic cultures, which still retain formality around public mourning.

Being two pieces of hair art related to individuals, these are the personal and reflect the nature of what the value system of the family was. Being pieces that can connect cultures through their symbolism and methodology open them up to being grand statements of the 19th century. Simple elements connect to grander thought and identity, leading to how and why people undertook the mourning rituals.

These are still relevant today, as Western values haven’t changed from what people identify with, humans have simple adapted to technology. Through mass transit and ways of cross-cultural pollination, the values of these art pieces will always be prominent; the grave, the weeping willow and the idea of death remain consistent forever.