Photography, Part 4

The precedent for post-mortem photography verges on the ancient, with funeral and post-mortem imagery linked to early cultural development. For the modern era, there was a renewed interest in deathbed paintings in the 1620s and 30s, with mourning as a social signifier entering the modern psyche. Post-mortem photography, however, began as quickly as the technology was adapted. In the United States, families were also changing from the community aspect to the smaller, family unit. During the 18th century, these Puritan communities would feel the loss of a single person as a loss to the community, whereas this had been restricted to the immediate family in the 19th century. Due to this and the greater freedom of the daguerreotype process in the United States (due to lack of patent control), post-mortem photography was widely prolific, more so than in Europe.

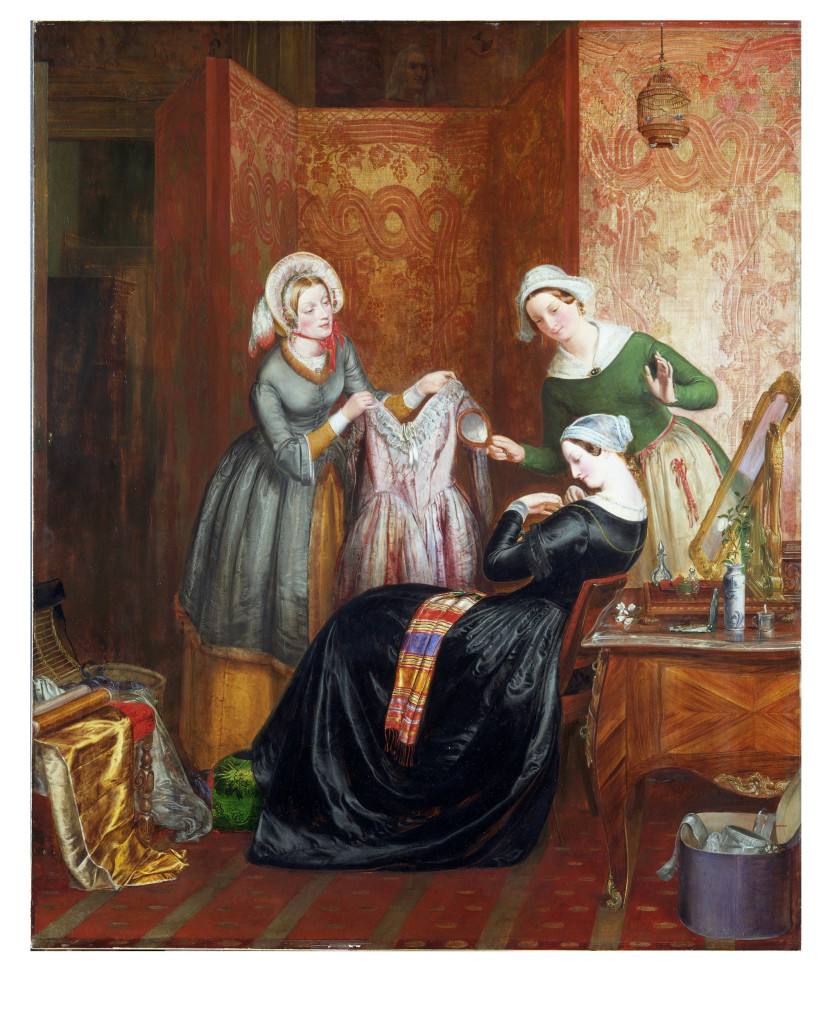

Early photographs were crude and the subjects were often not prepared correctly, but in a short period of time, the process was refined to studios and travelling photographers. As the style developed, the subjects became positioned and personal items of the deceased (or symbols of love) were placed around the body. Children are often the primary focus of post-mortem photographs and a great effort was made to make the subject look alive. For the photographer, making the subject look ‘asleep’ was one of the easier methods to do this, though studios specialised in ways to prepare the body for photography. These may be retainers to hold the bodies in position, massage to the limbs, rouging of the cheeks, ‘affixing the mouth closed with a forked stick placed under the chin and against the breastbone, closing the eyes with coins, and preserving the features by placing ice under the body.’ Different concepts were used in this method, but the primary focus was the same; to hold on to the memory.

‘…parents evidently desired to represent their dead children in all kinds of attitudes in order to express their intense grief and their passionate desire to make their children survive in memory and in art, to exalt the children’s innocence, charm, and beauty.’ Phillipe Ariès