Photography and Death

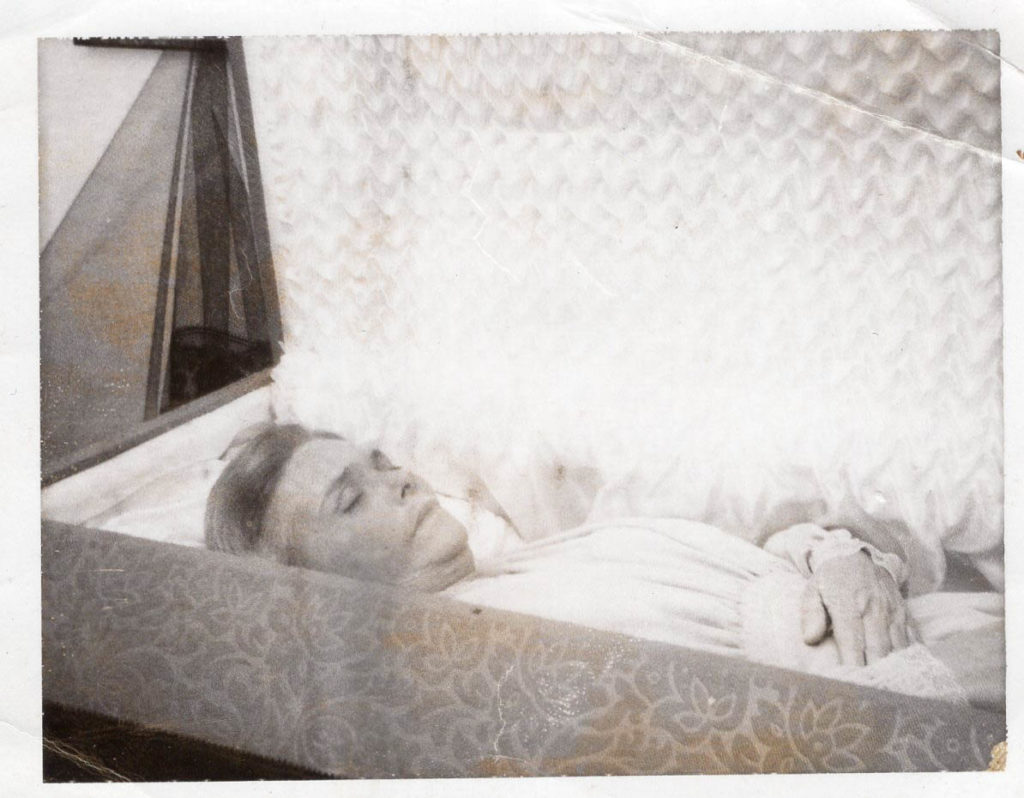

“The unusual example of the ‘double portrait’, housed in one case of the elderly woman alive and deceased makes a powerful comparative pairing. The subject’s resting pose of her crossed hands in the life portrait is intentionally and aptly echoed in the post mortem image.” – V&A Museum

For those who may be sensitive, this article contains graphic content. Please be advised to click away now or please read on.

Capturing the image of a loved one in their final moments before burial is the last moment for family and friends to hold a visual memory of them. This practice dates to the ancient, be it for a memorial to a deceased person in a monarchy, or for a loved one to be painted in-situ.

In the early-modern era, there was a renewed interest in deathbed paintings, particularly in the c.1620s and 30s, with mourning as a social signifier entering the modern psyche. Mourning practice and its industry developed in Protestant communities to reflect back onto the ‘self’, depicting memento mori symbols of death and decay to replace the Catholic Christian symbols. Mourning identity became more personal and focused on the desecration of the body, influencing a burgeoning middle class to remember that they will die, so live life to its fullest.

Funeral and post-mortem photography is linked to modern cultural development. The development of camera technology in the c.1840s allowed for a last memory of a person to be captured while they were lying in state, for personal purposes and the more sensational purposes, which relate to the 20th century. Displaying the body of an infamous deceased person in public had been popular throughout many moments in history, but the photography of photojournalists, such as Weegee (Arthur [Usher] Fellig), would also depict death to the public in a very confronting way.

Post-mortem photography began as quickly as the technology was adapted. In the United States, families were also changing from the community aspect to the smaller, family unit. During the 18th century, these Puritan communities would feel the loss of a single person as a loss to the community, whereas this had been restricted to the immediate family in the 19th century. Due to this and the greater freedom of the daguerreotype process in the United States (due to lack of patent control), post-mortem photography was widely prolific, more so than in Europe.

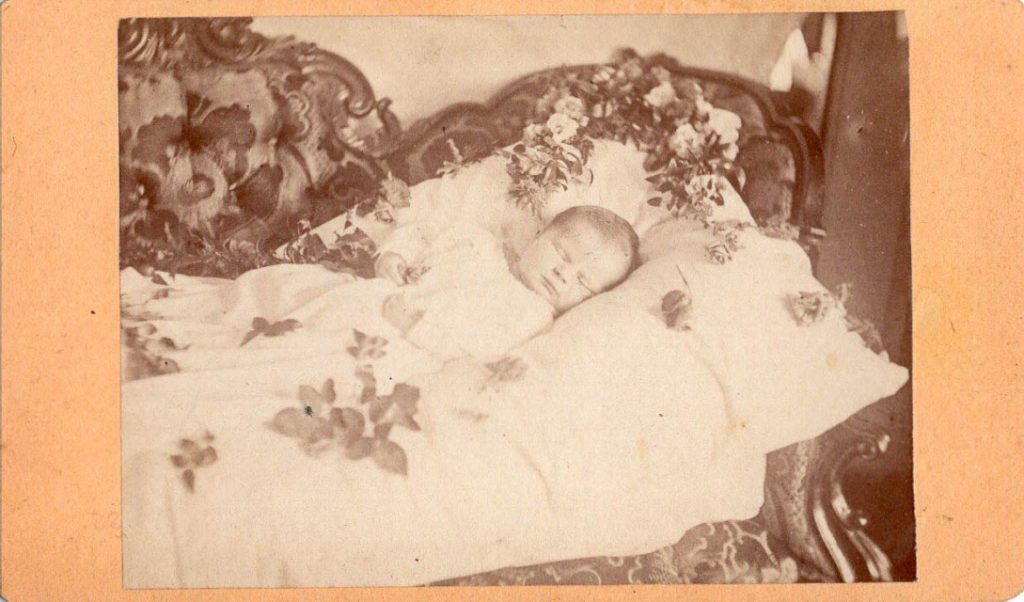

Early post-photographs were crude and the subjects were often not prepared correctly, but in a short period of time, the process was refined to studios and travelling photographers. As the style developed, the subjects became positioned and personal items of the deceased (or symbols of love) were placed around the body. Children are often the primary focus of post-mortem photographs and a great effort was made to make the subject look alive. For the photographer, making the subject look ‘asleep’ was one of the easier methods to do this, though studios specialised in ways to prepare the body for photography.

These may be retainers to hold the bodies in position, massage to the limbs, rouging of the cheeks, ‘affixing the mouth closed with a forked stick placed under the chin and against the breastbone, closing the eyes with coins, and preserving the features by placing ice under the body.’ Different concepts were used in this method, but the primary focus was the same; to hold on to the memory.

“‘…parents evidently desired to represent their dead children in all kinds of attitudes in order to express their intense grief and their passionate desire to make their children survive in memory and in art, to exalt the children’s innocence, charm, and beauty.’ Phillipe Ariès”

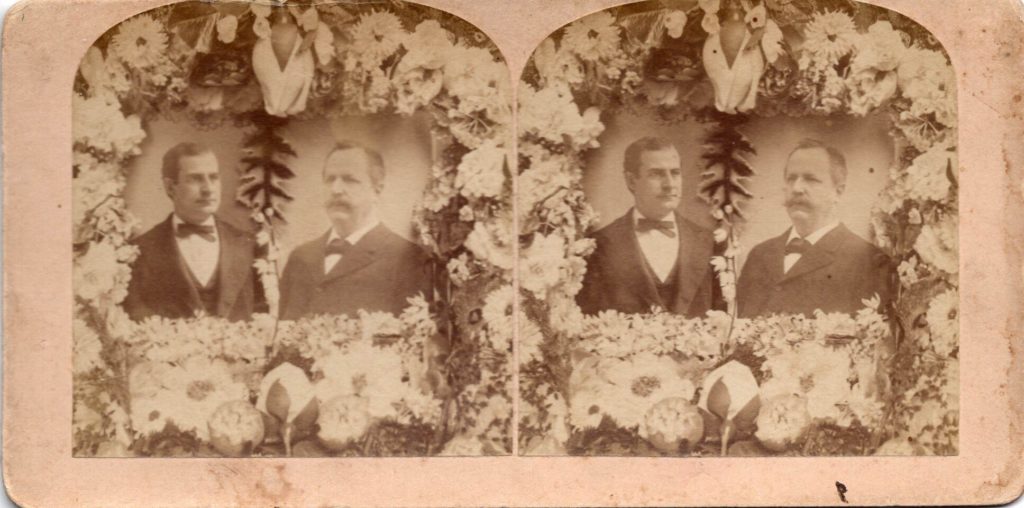

As print became affordable and accessible, items such as the Carte de visite and cabinet card were available with variations upon the post-mortem photograph. ‘Madonna’ images of the mother holding the deceased child, couples holding photographs of the deceased and more public cards showing the body of a famous person are all variations on the post-mortem photograph. One of the more interesting is the pre-mortem photograph, with the subject shown before death. This was an admittance of the mortality of the terminally ill by the family and these images are not prolific in the same way as their post-mortem counterparts. As soon as photography could be adopted as a viable means for mass print and accommodate customisation, memorial ephemera adopted the technology quickly. These often were images of the person in life, rather than in death, but the industry was large enough to adapt the photograph technology for different memorial purposes. Beginning in the 1860s, mourning (or funeral) cards are still used with personalised imagery today.

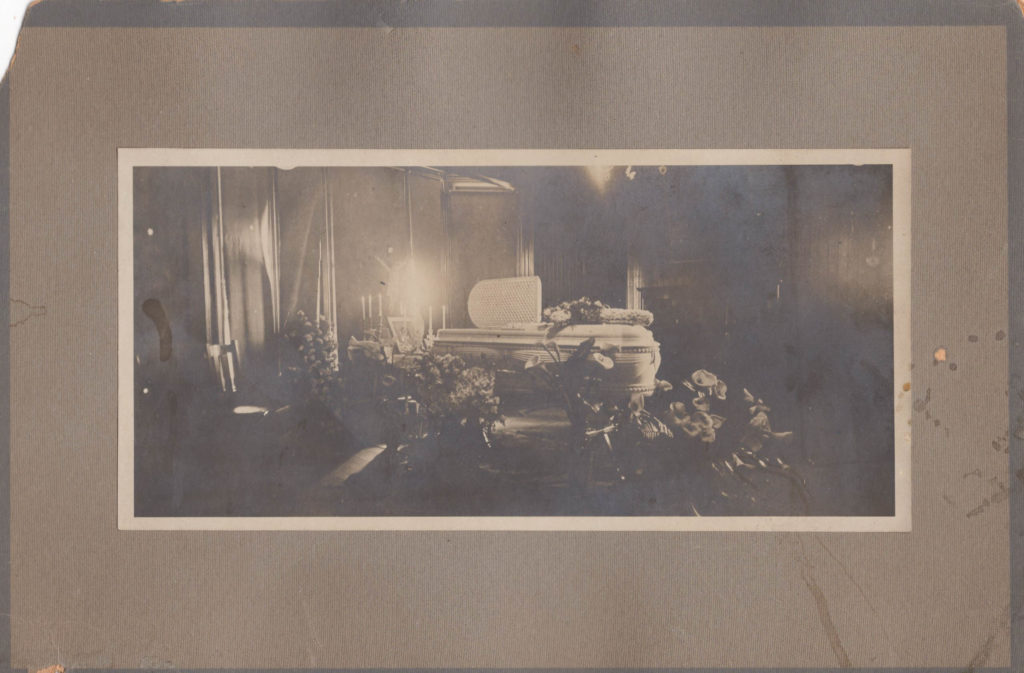

By the 1890s, post-mortem photography (as well as the mourning industry in general) was on the decline. Symbolism, such as the coffin, had replaced the body as the symbol of death and societies were distancing themselves from the image of death. Mortality rates were changing and the fact of death was evolving. Now, photographs were more inclined to show funeral arrangements or even the funeral itself. Perhaps the more melancholy imagery was that of the child’s empty shoes next to a memorial (though this was used during the height of post-mortem imagery as well). Post-mortem photography was kept until the early 20th century, yet more common were photographs of the deceased (while alive) used in memorials. The practice itself is a direct reflection of the family and incredibly personal to the family unit. Unlike jewellery or adhering to any form of mourning fashion to publicise the effect of mourning, the photograph held the memory of the person and should be seen as a powerful symbol of affection.