Onyx and Silver ‘IMO’ Victorian Hairwork Pendant

The second half of the 19th century saw the combination of mainstream fashion and mourning fashion. High mortality rates and a monarch who had entered perpetual mourning after the death of Albert, Prince Consort, in 1861 set in motion the iconic garments and jewellery that is identified as ‘mourning’ today. The abundance of black, both in costume and in jewellery, is highly identified for this time and it can make viewers lead to assumptions about any fashionable object that was black being strictly for mourning. Materials such as jet and vulcanite hit their peak during this period, but the vast majority of trinkets were for sentimental purposes and worn as such.

Utilising onyx as a material for mourning, as this locket does, establishes this piece to be of a higher fashion. Onyx was popularised in French mourning jewels, making their identification much easier than unmarked onyx pieces that were worn for their fashion. In the subject of this article, there is a perfect example of a fashionable mourning item, consisting of onyx, silver and an intricate, interlocking coral branch ‘IMO’ (‘In Memory Of’) design.

“Lockets, such as this superb quality mourning locket, were at the height of their popularity from the 1860s to the 1880s. They were even described as ‘indispensable’ in magazines in 1870 and 1871. They could commemorate a wedding as well as a death: in March 1871 Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Louise (1848-1939) gave a locket to each of her attendants at her wedding. E.W. Streeter, a leading London jeweller, offered a discount of ten per cent on bridesmaids’ lockets when ordered in multiples of six.”

“Onyx mourning jewels found favour in the highest circles. In March 1861 Queen Victoria ordered a number on the death of her mother, Victoria, Duchess of Kent (1786-1861), and more after Prince Albert’s death in December 1861. In 1872, to commemorate her half-sister, Feodora, Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, she gave a banded black and white onyx mourning locket to one of her granddaughters.” – British Museum

Style and status are the elements of the materials used in jewels from the second half of the 19th century. Previously, the advancing Neoclassical style had utilised gems and pearls, as access and cost would allow, creating smaller jewels with greater importance on hair as the primary sentimental token. Much of this was due to the impact of the Napoleonic Wars and having the market flooded with gems from broken up aristocratic collections in the European Continent.

With colonisation and empire building, access to materials allowed for artist to rise. Investors and new wealth began to advance beyond what was only attainable for the aristocracy, changing the perception of style following on from the nature of a queen or king. While these do remain popular catalysts today, makers such as Cartier and Lalique could create jewels utilising cheaper materials, such as diamonds and silver, which weren’t easily attainable.

From the 1860s to the 1920s, the world saw change like no other time in history, with continents drawn into conflict and cultural visibility and influence defining how one presented themselves within society. How this locket relates to this is by using the finer value of its time and becoming something that is highly fashionable and sentimental.

The Mid-Late 19th Century and Jewellery

Innovation led by Albert, Prince Consort cannot be understated for its values and impact upon society. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened. Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society, which is a progressive step and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

The 1850s led much of this standardisation, with the family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art. Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing.

Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century.

Bolder style was in its element during the 1860s. This can be attributed to the mourning of Queen Victoria from 1861, but also tells of the evolution in costume and everyday dress.

The larger styles of the mid-Victorian era had taken hold, with female fashion becoming larger and the jewels needed to adapt.

By the latter century, costume and function were tightly connected for women. Dresses of separate bodice and skirt were worn in bombazine covered in crape. Underwear was often white chemises, drawers and under petticoats slotted with black ribbon. Black caps, crape trimmed bonnets, and long veils.

c.1870. ‘In Memory Of’ Brooch with Onyx

First mourning lasted one year and a day, outdoor garments for this would be shown by the plainness and amount of crape, jet jewellery was permitted. After one year and a day, Second stage was introduced. This involved less crape and its application to bonnets and dresses became more elaborate. It was frowned upon if this period was entered into too quickly and it lasted nine months in all. The Third stage (or Ordinary stage), introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted.

Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months. The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life. Hats, shawls, mantles, gloves, shoes, fans all changed during mid century, and pagoda sleeves from 1850-70 were fashionable, designed to be stitched to the outer sleeve to cover modesty from the lower arm and wrist. Wide skirts from the 1850s-70s, tie back fashions of the late 1870s and the ‘S-bend’ look of the early 1900s all were adapted to mourning fashion, without a clear definition of difference between them. Throughout the post 1880s decline, in the 1890s, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure.

Onyx and Chalcedony

Use of onyx dates back to the ancient, with reported usage in second dynasty Egypt, but most typically Greek and Roman. It is a banded form of chalcedony, with its most popular colours being black and white, yet there are multiple variations of colour found in its bands. It shares the similar jewellery carving hardstone qualities as agates, jade and rock crystal. Because the bands of onyx are aligned with each other, carving the cameo in high relief makes for highly detailed jewels.

In the case of this ring with the urn and willow, there is considerable detail to the urn itself, with a very sharp styling to the willow. Note the etching to the depth of the leaves and the branches of the willow for how detailed the design is. Artists of quality could define a depiction with elaborate detail to a cameo or intaglio, where even high-relief profiles were carved to perfection. In this case, however, the carving is detailed, but not delicate, utilising many strong, sharp lines and little use of curves.

Chalcedony is a term that refers to many varieties of cryptocrystalline quartz gemstones, ranging from sard, plasma, parse, bloodstone, onyx, sardonyx, carnelian, agate and many more. Early human use has been found for knives, tools, vessels and other such primitive tools. Later examples carried through history, from the creation of cylindrical seals in Mesopotamia in from the 7th century B.C.E, through to Mediterranean-based civilisations in buttons, cameos and intaglios. For these brooches, one must consider the necessity of the style in fashion and how this material could benefit its use in jewellery.

As is the case with many influential materials in jewellery construction, the access to cheaper materials often define the style which comes from it. The town of Idar-Oberstein became popular in the 19th century for its processing and carving of Chalcedony, with cheap importation of mining from Latin America. Due to its history dating back to Roman times, Idar-Oberstein provided raw agate and jasper, with a lapidary industry appearing in the 15th century to finish the materials.

Leading to The 1920s

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

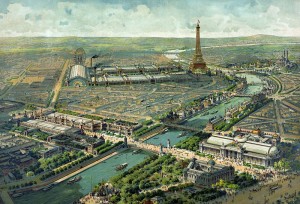

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

This is why the Paris Exhibition was so fundamental in disseminating new styles throughout mainstream culture. Wealth from America and driven by industry was empowering artists to go beyond the Court/aristocratic styles that hadn’t had the early 19th century monetary drive and lockets such as this ampersand piece could thrive. Look to the design of this piece; the Nouveau elements, from the organic curve to the floral outcrops.

Post War Mourning & Sentimentality and Photography

The decline of the mourning and sentimental industries was not exclusively ‘mourning’ related, but an actual change in fashion and social taste. How to present sentimentality and love in a public forum through a jewel was very different in the post 1901 environment than it had been since 1861. Two generations had passed under a very static monarchy, which originally had been the cultural impetus for fashion and art. Society would look to the monarchy for various elements to adapt, the most noteworthy being George IV, but Queen Victoria had established the ‘ideal’ family unit under a Christian value system and then fallen into perpetual mourning. Despite the underpinning realities which may contradict this, it was then, and still remains, a value system that Western cultures still use today. Everything from the establishment of wedding ritual to Christmas rituals and their surrounding affectations are built from the 1840s, yet there was a rebellion in society that needed to create its own style and movement to break apart from what was considered a rigid perception of mainstream fashion. This change came about in the 1890s.

Throughout the post 1880s decline, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure. While this perception is very affecting to mourning, the sentimental industry and its production of jewels as tokens of love were changing rapidly. There were art movements, such as the Arts and Crafts movement, which built upon the ‘natural’ elements of beauty and design to be interpreted in architecture and industrial design. This was a counter-reaction to the industry that had dominated 19th century life, by moving back to organic styles. This is much the same as the Rococo movement in the early 18th century, which reacted against the dominant Baroque styles with organic flourishes. This, in conjunction with the Enlightenment, led to new perceptions of the self in the Neoclassical movement and in the late 19th century, we see the same revolution in cultural style.

Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 created the catalyst which led to the new generations establishing their own styles as the new social revolution. From an inward-out perspective, the English looked to France and America as being the leaders of influence in style and these adaptations had a massive impact on jewels of the time.

But that is not to say that jewels of the 19th century ceased to have their impact. The gypsy-set jewels of the late 19th century were still popular, as well as many of the existing styles which could be purchased in catalogues. Hairwork and mourning jewels suffered, while a new Romantic movement led to miniature portraits, love tokens (heart shapes, particularly) and narrow brooches with simple and direct symbols set with gems. The difference here is that the Edwardian jewels were built around the artist and designer. Jewels that were a step beyond the catalogue-bought styles focused upon new artists, such as René Lalique, and the rise of competing art movements to represent these styles in jewels.

Even for World War I, with an estimated thirty-seven million casualties, a mourning industry to rekindle the previous generation, did not happen. Different sentimental elements, such as the giving of a watch chain to wear as a necklace, became sentimental keepsakes, rather than a proper dedication in a ring.

Photography is the final key factor in the depiction of the self. Its impact on jewellery design cannot be understated, as the capturing of an image of a loved one overcame the capturing of a piece of that loved one in hairwork. Much of this change is why the perception of having the hair of a loved one in a jewel is considered morbid today. Why have hair when a photograph was nearly instantaneous and within the budget of a working class individual? Better technologies led to photographs having smaller sizes and that led to smaller jewels being constructed around this form factor. In this jewel, we see the elements of the heart and the photography combined with a cameo of the female denoting a loving piece for its time.

A Solid Statement of Mourning

As can be seen through the story of this pendant, the sentimentality of the onyx being a statement of eternal mourning and the ‘In Memory Of’ statement (woven from the coral sentiment meaning ‘thy choicest jewel is thy heart’), the pendant is a time capsule for developing society. Much like communication, our methods of mourning and grief don’t change, it is only the way we adapt with the materials we have around us. This pendant speaks the same today as it was when it was created, but perhaps without the instant recognition of the ‘IMO’ statement. This was fashion and grief bought together for the purpose of a loved one trying to keep a memory alive.