Looking at Victorian Bracelet Clasps

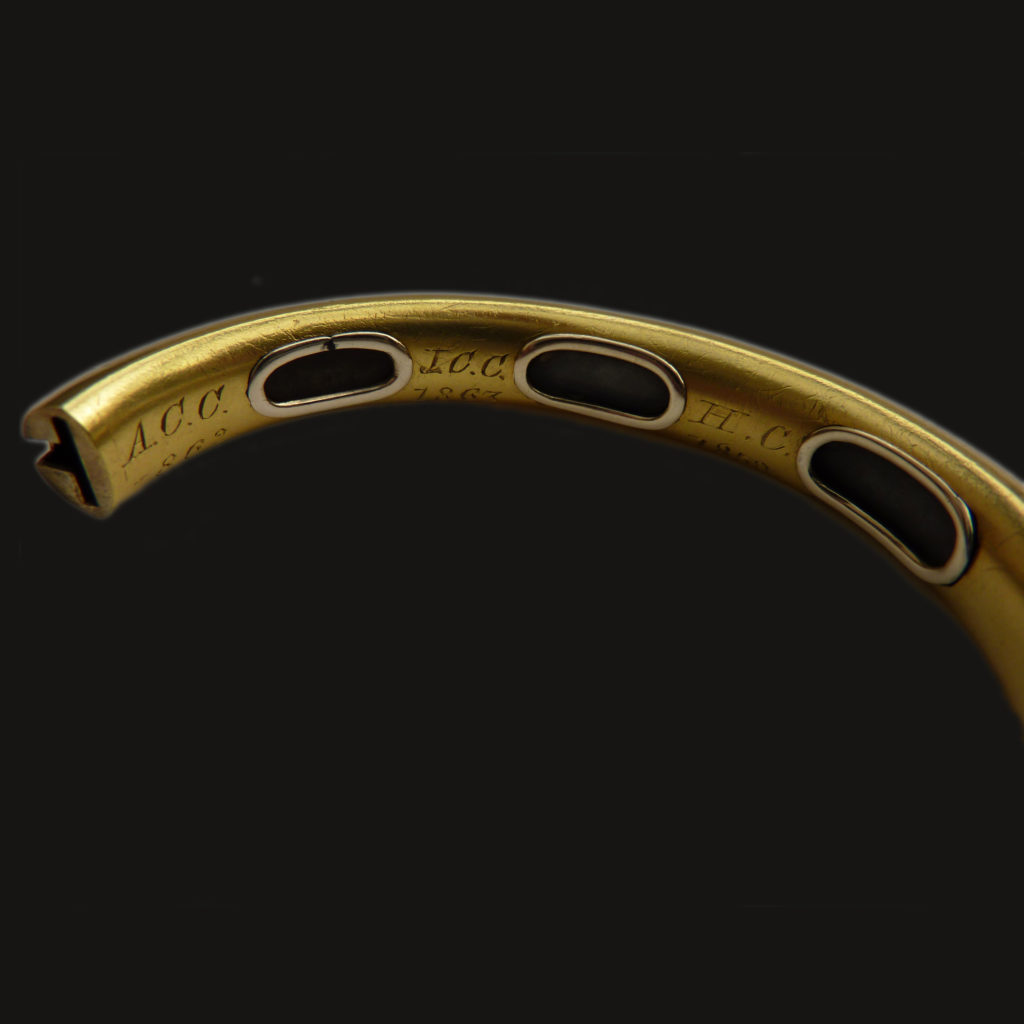

Clasps can define the age of a piece or make it more desirable than another. Many hairwork bracelets have been destroyed over time in order for jewellers to retain the gold fittings and remake them into other bracelets. Above, the example has a twist clasp that is quite difficult to open.

Bracelet clasps are often the most important part of the hairwork bracelet itself. This is the connection between the hair with unifies and creates the loop. This is what symbolically can reflect what the wearer of the bracelet is trying to convey. In this example, the eternity knot substantiates the loving bond between the wearer and the giver of the hair.

Knots in jewellery and their particular focus as a symbol of eternity and love rare ancient concepts that span both the East and West. We’re blessed with how prolific they are in mourning and sentimental items for the very nature of their symbolism, but their appearance in different permutations in cultures is ubiquitous and strangely correlating with concurrent meanings.

Why would this be so? Well, let’s take a look at the knot itself. The symbol itself is woven in on itself, enough to consider that two individuals are tying together to establish an interwoven union where two become one in the symbol. Next, there is the understanding of the knot becoming tighter as the two ends become further apart. Once again, distance only makes two people closer through its very nature. The knot also loops around on itself and travels in an eternal twist, for the love between the couple is forever undying. Put all these together and you have a rather special and beautiful symbol, one that encompasses much of the basis of what sentimental jewels are created for.

“In the seventeenth century, one or two of the bride-favours were always blue. These were knots of coloured ribbons loosely stitched on to the wedding gown, which were plucked off by the guests at the wedding feast, and worn as luck-bringers in the young men’s hats.”

However, we’re here for jewellery, so where can you find the knot and what would you expect?

For Neoclassical pieces, you can’t go much further than the depiction above that explicitly uses the knot as a primary symbol and sentiment. Look for the knot to appear in many Neoclassical mourning and sentimental depictions, either as an overt statement or relegated to a symbol being held by a central figure or as a flourish depicted in the art. Often, this can be as subtle as a knot painted onto a plinth or tomb.

In hairwork, the knot is quite often displayed with the hairwork of a couple being interwoven and the symbol itself is implied without appearing as the primary focus of the symbolism itself. This is quite common from around the 1780s to the late 19th century in bracelet clasps, brooches, rings and other forms of peripheral jewellery that would house a hair memento.

So, there you have it! The knot is quite a popular and commonly used motif today as it was then. Much of this has to do with its very eternal nature and pure connotations, free from everything but the most simplistic concepts of love and affection.