Jewels, Memory and Photography

Despite the title of this dissertation in mourning and sentimental jewellery being ‘Art of Mourning’, the primary message of the jewels that are discussed is based firmly in the elements of love and memory. A jewel being worn for someone alive or deceased is not the interest that should be discussed, rather, it is the importance and value of the person who wore them. In this article, let us look at a photographic collection of jewels and how they were worn to discover the fashion and cultural values of sentimentality throughout the 19th century.

Through this article, we will visit a brief history of photography and the technologies that popularised it throughout the 19th century. Photographic technology was one of the main catalysts for the decline in miniatures in the 19th century. It correlates to the availability of the technologies and the decline in cost of photographs. Naturally, the ability to capture the image of a loved one, or even a collection of loved ones, is an even closer way to connect to the subject of love and memory. During the 19th century, the following technologies developed for dominance in an increasingly lucrative market:

- Daguerreotypes

- Ambrotypes

- Tintypes

- Cartes de Visite

- Cabinet Cards

Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre popularised his patented photographic technology through being a talented promoter. Having a history in commercial art and theatre production, Daguerre received a French government grant for a pension to be recognised as the inventor of this technology. The popularity of the daguerreotype led to over 70 photographic studios in New York City in 1850, a massively rapid uptake since its inception in 1839. As such, the daguerrotype reigned as the most popular photographic technology, until ambrotypes took the market lead, due to their being less expensive and easier to produce. By the 1860s, daguerrotypes were considered obsolete.

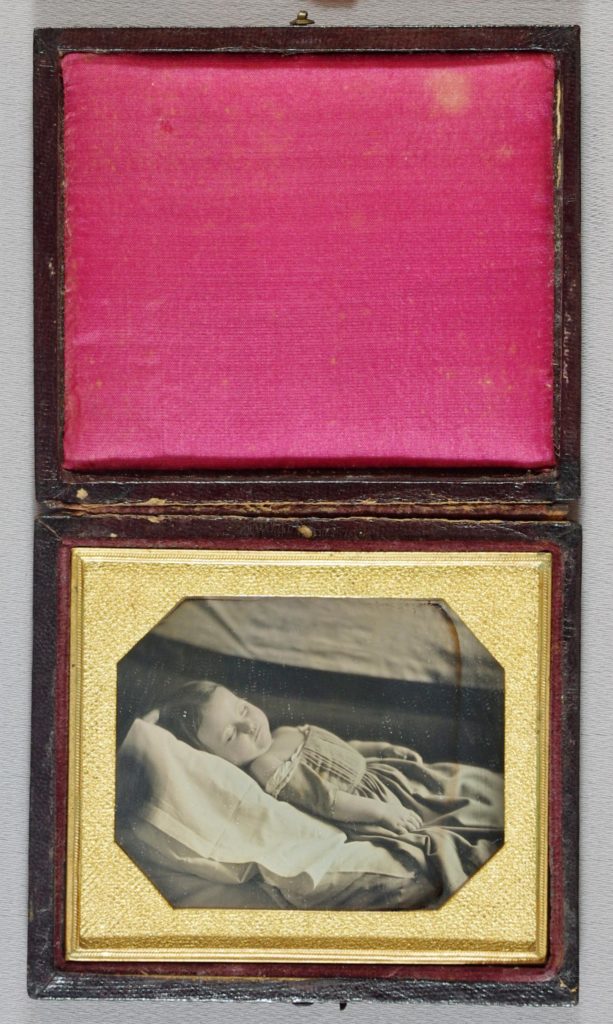

c.1845-1855, slightly hand-coloured sixth plate daguerreotype mounted in hinged wood embossed leather case.

While still fragile, the ambrotype had a short lifespan, which was the late 1850s-1860s. In 1854, the American James Cutting patented a process that produced an impression on glass. High quality glass was treated with light sensitive collodion, then exposed in a camera, this produced a glass negative. The reverse of the glass was coated with a black varnish, or a black mat, which produced the ‘positive’ image. Coloured glasses were used to replace clear glass in the late 1850s, producing a rich image, which also made the blackening of the glass reverse redundant. Out of the coloured glasses that were popular, ruby was the colour of choice. Due to sensitivity, tintypes, daguerrotypes and ambrotypes were sold under a layer of glass to preserve them from crayon, pastel and oil paint colours, when colour was applied to the image, as seen in several of the images in this article.

Colouring a photograph for a grander sentimental effect can be seen in the below portrait of a lady. Her necklace, brooch, bracelets and ring are all highlighted with gold, denoting status and the importance of the jewels. Sentimentality, when worn on the body, is important for place and time. These artefacts are a window into the life of the 19th century person, from the fashion, to the importance of status in what was worn.

More colouring to the photograph shows once again the importance of the gold to the jewellery. Her cheeks are also highlighted, bringing an animated life to the image. She appears facing the camera in a very natural pose, which makes the subject alive and engaging with the viewer. With her situation combined with the jewellery, the sentimentality is apparent. She wears a wedding ring on her left hand, which is highlighted by the gold, and the large brooch to her neck is the height of fashion. Crinolines and large, voluminous sleeves needed to be balanced with larger jewellery, causing styles to become larger. The Hallmarking Act of 1854 allowed for the use of alloys in jewellery, which made other options like Pinchbeck to become popular, as they appeared solid and large, yet were light and cheap to produce. Here, the costume balances well with the low collar and the brooch at her neck, a brooch which seems flat and large, indicating that it could indeed be solid and quite expensive for its time.

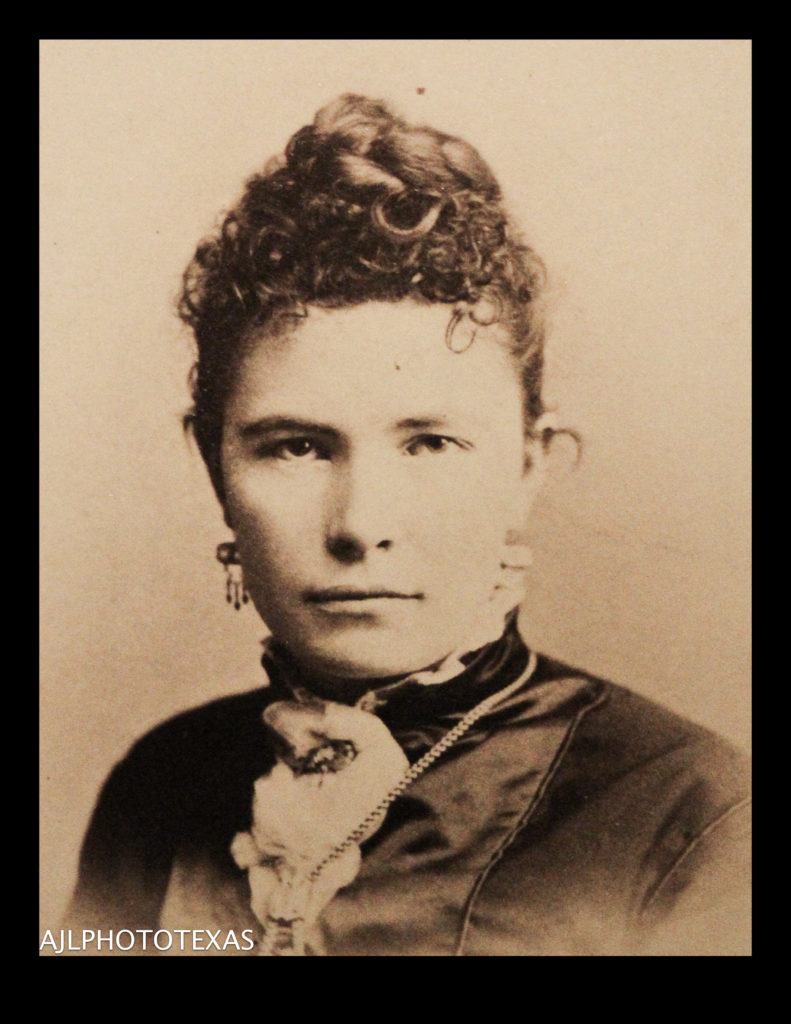

Possibly the most arresting element to this photograph is the sentimental brooch she wears at her neck. The brooch is large and fits in appropriately with the style set in c.1860 for popular sentimental jewels. These are generally hollow, with a classical cameo in the interior, photograph, or a placement of hair under glass. Her long drop chain necklace and ring on the index finger are also highlighted, making them the focus of the image. These are important identifiers of status for their time, making the combination of jewels not only sentimental in intent, but fashionable for a lady. There’s no clear indication of marriage in this image, but the portrait could have been given as a loving token of memory for a loved one.

Brooches were at the height of fashion in the mid to late 19th century, due to their size and position of wearing. Commonly worn at the neck, brooches would take the status of a personal value system, as they could denote the person being in love, mourning or just simply fashionable. It is interesting to see how the brooch evolved through the 19th century, from the smaller, oval and rectangular shapes, which could be pinned at the bodice, to the larger, neck position. As previously stated, the 1850s allowed for alloys to be used in fashionable jewels, where they could be lighter and larger for larger sized fashions.

Domed skirts grew larger with flounces, which were cascading ruffles, creating a larger and fuller skirt. In 1856, the steel cage crinoline enhanced the oval shape of the dress and eventually removed the flounces, offering a smoother skirt over a petticoat. What is important to note is that the conservative Christian values implemented in the 1840s required a level of modesty in costume that had not previously been in place. Covering more of the body with clothing correlates with the necessity of jewellery. Having more values that place jewellery in a sentimental paradigm for status relates directly back to social implications. Hence, the values of where one wore jewellery and how one wore jewellery were more necessary than previous generations.

Look at the previous images and see how they all justify a certain style of their time. They are fashionable, but they are all contextually relevant. For the pieces in the mid 19th century, the brooch, ring, earring and necklace combination all work within the fashion that is similar throughout each image. In the latter 19th century images, the high collar and pinned brooch all are similar in their status, without much variation. These are the things to observe when looking through images in the 19th century.

By the mid-century, photography had become the affordable token of remembrance and sentimentality that jewellery rapidly adapted to. Technologies, such as the tintype, were an incredibly popular photographic method in the 19th century, being produced into the 20th century, notably as souvenirs. The process for developing the tintype were much the same as the ambrotype, but iron was used instead of glass. An iron plate was coated with a black lacquer to provide a smooth surface, on which the image would be developed, this same lacquer would prevent the iron from rusting. Due to the misnomer of the tintype being actually iron, they were also referred to as ferrotype and melainotype.

To be successful, popular sentimental tokens need to be faster to produce and more cost effective. As a token of affection and a personal souvenir, the carte de visite was an economical alternative to the tintype, as the image is developed on paper. High quality paper was coated with albumen (made from egg whites and sensitised with a silver solution), which yellows and gives images the image sepia hues. Originally mentioned in Photograph Manual: A Practical Treatise (1862), they were eventually refined into cabinet cards.

By the 1880s, cabinet cards became the preferred photographic method until the end of the 19th century. These were nearly double the size of carte de visite’s, yet were made through the same format. Though the spatial area was larger, the quality was the same, however, camera, paper technologies and improvements in the 1880s led to better definition in image.

Seeing jewels in-situ brings us back to the central conceit of why they were worn. Memory is the most powerful, yet fleeting, factor of the human condition, with a constant drive to recall a time, a moment or a person. The photograph allows us to look back in time and see the pride, love and fashion that was on display when a person proudly wore a jewel on their body. As can be seen from this collection is that these all have consistency in the importance each subject imbued within the photograph. There’s nothing arbitrary about the costume, poise or stage that the photograph maintains; each and every one is a loving testament to memory and love.