Jet

Due to its black colour and easy translation into mourning costume, jet is a material which suffers from mourning connotations, when however it is one of the oldest jewellery constructing materials used and a fashionable material to wear. In actuality, mourning has a very small role to play in jet jewellery when one considers the scale of the industry and contemporary fashions, hence why it’s not a subject I cover often on Art of Mourning. However, it is a fascinating material and it does have a strong role to play if your focus is on 19th century mourning, so an analysis of jet is important for historian and collector.

What is Jet?

Jet is actually a type of brown coal, or fossilised wood of an ancient tree, containing around 12% mineral oil with aluminium, silica and sulphur. The trees which grew to produce this were similar to modern Araucaria trees and date from around 180 million years ago. Upon its death, a tree which fell/was carried to a body of sea water would become broken and waterlogged, then sink to the bottom and remain there to be covered by sediment. As it remained there, it would become compacted by the pressure and over time the wood would convert to jet. Chemical analysis has shown that jet was formed under sea water, however it has been suggested that softer jet was formed under fresh water.

Despite the names of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ jet, there is not a great difference in density between soft and hard, simply that soft jet is quite brittle and often cracks when heated.

The Romans coined the term ‘black amber’ for jet, as in the 19th century they had considered jet to be a hard resin. Jet conducts static electricity when rubbed on silk or wool and is also light, but under intense magnification, jet shows its origins as a product of wood.

Found in Russia, Germany, Turkey, France, Spain, Portugal, North America and of course, England, various densities of jet were mined and used, however the finest is considered to be from Whitby. Mining jet in Whitby began c.1840 and lasted to 1920, peaking in the 1870s with between two hundred and three hundred miners.

Early History

‘It is black, smooth, light and porous and differs but little from wood in appearance. The fumes of it, burnt, keep serpents at a distance and dispel hysterical affections… A decoction of this stone in wine is curative of toothache…’ – Pliny, Natural History, 1st century AD

Jet’s history dates to the prehistoric, as it was a material used for various artefacts (amulets, shaped as animals, beads, combined with amber, bones, teeth, etc) dating back 10,000 years in the France, Germany, Switzerland regions. More complete pieces have been found from Yorkshire to Scotland from 4500 years ago.

Romans used jet for rings, bracelets, dagger handles, necklaces, hairpins and die and excavations have found workshops dedicated to jet production in York (Eburacum). Pieces of possibly York origin have been found and are on display in Cologne.

In America, Pueblo Indians (around the Utah and Colorado regions) produced jet jewellery, combining it with shell and turquoise, which, in light of the Spanish jet industry, pre-dates the Spanish arrival in the area.

As a popular and reasonably simple material to carve and construct items from, jet never completely disappeared as a usable material. It leant itself well to medieval construction, due to its properties of keeping away evil spirits and ecclesiastical jewellery used jet as a material liberally. By the 14th century, a jet industry emerged in, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany. Jet turners and carvers formed separate guilds, producing mostly ecclesiastical jewellery, declining only by the point of the Reformation.

Late History

Despite the lack of a large jet industry in Whitby post-Roman times, jet was known and referenced during the 18th century, but products tended to be mostly crude.

Muller argues that the transition from lighter Regency-era dresses to the heavier crinolines and larger styles of the 1850s and 1860s required larger jewellery to work with them, hence jet’s lightweight appeal and larger size provided to perfect accompaniment. Jet was presented to the public at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its popularity grew exponentially, facing almost immediate Royal patronage from France, Bavaria and of course, England. Thomas Andrews was the ‘jet ornament manufacturer to HM the Queen’ from 1850, and this would be a most prodigious position to hold, as upon Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria only allowed jet jewellery to be worn at court. Society followed on from court etiquette and mourning fashion and culture swiftly became part of mainstream culture.

By the 1870s, the annual turnover of the Whitby jet industry was said to be over one hundred thousand pounds, with a jet craftsperson earning between three and four pounds a week. From 1832, there were only two shops employing twenty-five people to 1872, where two hundred shops employing fifteen hundred women, men and children, taking over the landscape of Whitby. Development of machinery, such as the lathe, also helped to facilitate the growth of jet production meeting the high public demand for jet pieces. However, demand was so high that soft jet was imported from Spain and France, mainly for beading (as previously mentioned, soft jet tended to crack and many surviving pieces reflect this today), giving the jet trade what was considered to be a ‘bad name’, hence the attempt in 1890 to trademark ‘Whitby’ as a quality of jet. Jet was also seeing great competition in lesser-quality imitations which were far cheaper and by 1936, only five craftsmen were left. By 1958, the last Victorian trained jet carver had passed on.

But was it just the competition of imitation jet that started its decline? The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways. Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

Use in Mourning Costume

Jet was a wonderful material for use in mourning, obviously for its black nature and how that relates to the 19th century stages of mourning. First mourning lasted one year and a day, outdoor garments for this would be shown by the plainness and amount of crape, jet jewellery was permitted. After one year and a day, Second stage was introduced. This involved less crape and its application to bonnets and dresses became more elaborate. It was frowned upon if this period was entered into too quickly and it lasted nine months in all. The Third stage (or Ordinary stage), introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted. Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months. The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life. Hats, shawls, mantles, gloves, shoes, fans all changed during mid century, and pagoda sleeves from 1850-70 were fashionable, designed to be stitched to the outer sleeve to cover modesty from the lower arm and wrist. Wide skirts from the 1850s-70s, tie back fashions of the late 1870s and the ‘S-bend’ look of the early 1900s all were adapted to mourning fashion, without a clear definition of difference between them. Throughout the post 1880s decline, in the 1890s, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure.

Use in Jewellery

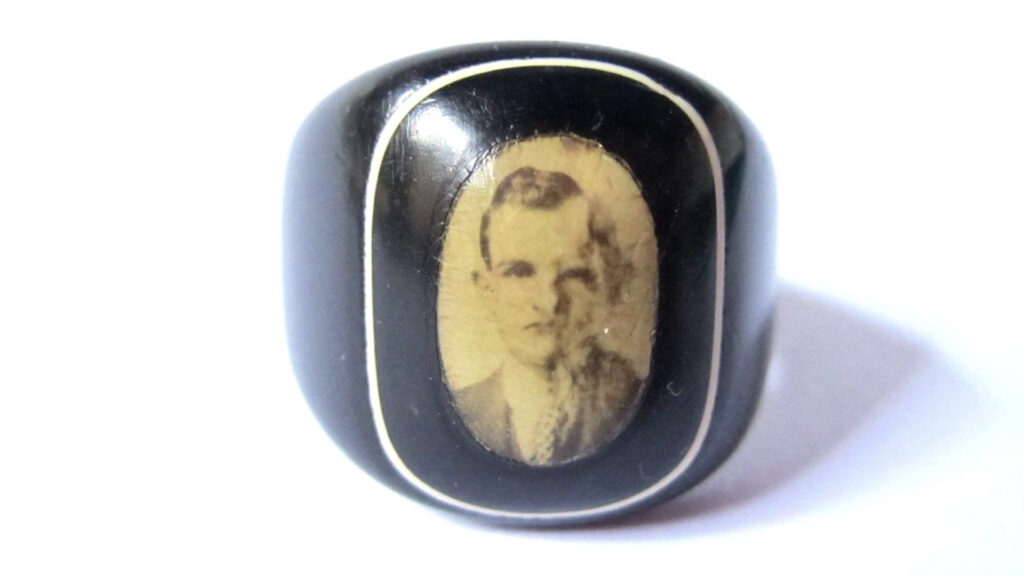

One thing that is important to note is that jet wasn’t simply a mourning material, which is often a common misconception. It was another jewellery material and quite fashionable, hence giving tokens made from jet doesn’t in any way denote death. Often its black nature and use in early stage mourning gives the impression that it automatically defaults to death. However, brooches from the 1870s, pendants, lockets, trim, beading, necklaces and personalised mementos (such as pins) are quite commonly found as love tokens and items held in high fashion, with only a small percent being used directly for mourning. Jet was also used as a secondary material in many rings, such as jet beading surrounding a ring’s hair memento, creating wonderful embellishments. The ability for jet to be highly polished made it a lustrous and attractive material.

What to Look For

One of the problems with jet come from the multitude of imitations made to replicate it. Once can discover the origins of a jet piece, as it produces a brown streak when rubbed against porcelain, is warm to touch (as it is a poor conductor of heat and a glass imitation would be cold in comparison) and if you heat a needle and put it to a piece, it will give off the faint smell of sulphur. Look for imitations of jet where the piece looks like it’s moulded – jet was carved and couldn’t take the obvious rounded shapes of horn or Vulcanite.

Further Reading

Hellen Muller’s exceptional book Jet from Butterworths is a collectors primary point of reference to learn more about this remarkable material. Muller is without a doubt the leading historian on Jet and its history, so if you can track down a copy, prize it in your collection. I would also like to thank Muller for without whom, this article would not be possible.