A French Mourning Pendant in 1787 For A Child

One of the most difficult concepts to gasp when identifying and appreciating mourning jewels is trying to separate the emotional context from the facts of the piece. In most cases, a simple evaluation can extrapolate what the jewel is, when it was created and who it was created for. These jewels are monuments, fashionable tombstones that are worn within a culture to depict the very nature of grief.

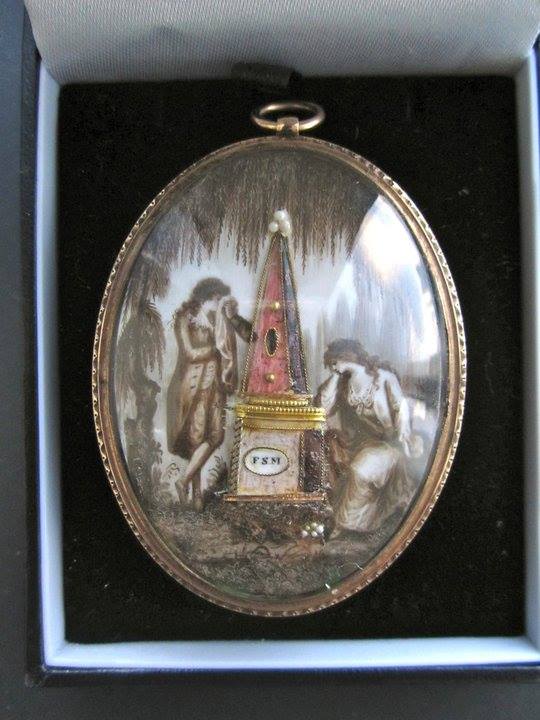

If that gravity was ever felt, today’s mourning miniature is laden with the raw emotion of the very people who held it. It is a snapshot of an era which focused upon what it was to be human, after generations of venerating an all-encompassing God as the singular method of living. The requirements of this miniature are so granular in their detail that its owners are captured in grief; the husband and wife flanking the plinth and obelisk. Tomb scenarios are the cornerstone of the Neoclassical mourning experience (c.1760-c.1820); consistently being the central object of mourning symbolism used across every form of jewellery that could accommodate its design. Jewellery could easily accommodate this symbol, as it was the tomb and the urn scenario which led to the expansion of jewellery size. Jewels became a canvas for the art of the Neoclassical period, not just a housing for a gem, a jewel could tell a tale.

The tale this mourning miniature had to tell was the following. Translated from the French inscription:

“Francoise Antoinette Elizabeth Martin, adored daughter of Francois Martin and Marie Susanne. Died in the arms of her father and mother on February 22nd, 1787, age 11 years, 4 months and 22 days.”

Two years before the French Revolution, this symbol of personal grief was created and houses a variety of different symbols to make up its whole. Its existence is due to the fact that Elizabeth Martin passed away on February 22nd, 1787 at the age of 11, which makes the miniature worth more than any of the materials in its construction. Indeed, not one of these elements can overcome its fact.

Catholic influence within French society contrasted with the Neoclassical (and in general, fashion leading) values that were represented within society. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought.

By the time that this miniature was created, it has the input of Neoclassicism being popular for around thirty years, which is enough time to perfect its craft, as well as Catholic challenge through Protestantism and the rediscovery of classical heritage for well over a century. The humanistic approach to this jewel is not uncommon for its place and time, nor is it a challenge to its understanding of religion and values, but it is at the forefront of what mourning fashion was and how it was adapted. British values added more symbolism into the style of this piece, but this piece would dictate what that style was. Making the human element so prominent, right down to the physical costume of the mourning couple, use the canvas of the jewel to represent the time in a naturalistic way. It is what it is for the value of capturing a moment, not adhering to the values of Neoclassicism for its affectation. In much the same way as a photograph would capture a moment today, this miniature did the same. This is shown in how the miniature would have been handled, as well. Not necessarily worn (sometimes at the neck), but kept within a compact when travelling or displayed in the home, they were keepsakes for remembrance.

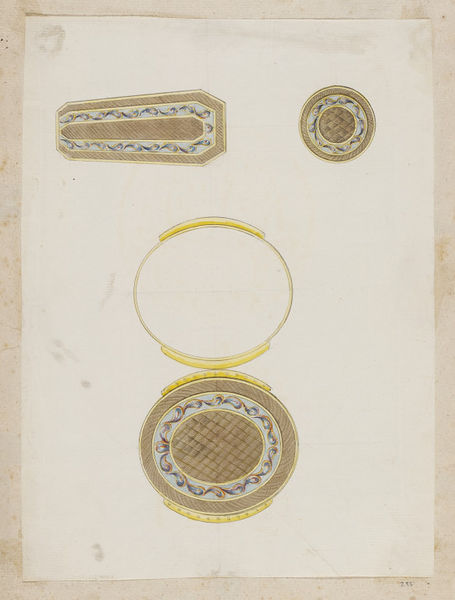

Jean Ducrollay, mourning set consisting of a miniature case for attachment to a ribbon, a coffin-shaped snuffbox, and a small circular box

Jean Ducrollay (1710-1787) designed the above late in life, which date from an album which includes snuff boxes, scent holders, watches, spoons, fan/mounts, swords, chatelaines and watch cases. It shows a mourning set of a miniature case for an attachment to a ribbon and a snuff box in the form of a coffin. Here, we see the values of memento mori aspect of what life’s meaning equated to in a contemporary time. Given that these designs were created close to when the mourning miniature was created, there is an element of style which connects the previous memento mori (“remember you will die” / 16th-mid 18th century) mentality to the Neoclassical. Fashion is the true driver here, as the aspects of the coffin-related snuff box are adorned with the white enamel pattern of the late 18th century. It’s a mix of the value of Catholicism and Protestantism as shown through the light of Neoclassicism, though this piece is more fundamental to the former.

Take into light the above design for a French mourning pendant cross, c.1780. It was possibly made for an elite client of the Court of Louis XVI (King of France from 1774-1792). It is inscribed ‘Cristaux. noir’ (‘black crystal’ with carat weights). As this cross was going to be decorated with black crystals, it was used for the ritual surrounding death. Once again, we have the connection of the ecclesiastical in death, this time, much closer to the crown itself. Just as the Ducrollay snuff box, there’s the element of death and God being connected through judgement, rather than what this miniature offers, which is the immediacy of mourning through the individual. The miniature of this article doesn’t consider what comes next, it simply deals with the grief of parents.

Jewellery dictated its form through the styles of popularity at the time. As this French, Neoclassical ring shows, the 1780s France adorned style with natural representation. Other than simply utilising every classical symbol for personal representation, here the gold urn in seed pearls shows the floral forget-me-nots and elaborate decoration in fine form. Fashion of fine gold and the access to seed pearls from the Orient made for highly detailed and inexpensive jewellery. Large enough to be seen and influenced by the Neoclassical style, this was a society adapting to the hardships that they were surrounded by. The seed pearls, as seen as decoration in the mourning miniature at the tip of the obelisk and foot of the tomb aren’t precious, but easier to access, hence they are seen in many of the jewels of the time, just as this ring shows them in its excessive three-dimensional design. The urn comes to life through the pearls, which begin to take on a sentimental narrative for their usage (tears).

Enamelled gold ring set with a watercolour on ivory silhouette and on the back, a panel of woven hair under glass

‘I cherish even her shadow’, speaks this ring to the viewer. The ring shows a silhouette set in ivory with a royal blue enamel border and a panel of woven hair under glass on the reverse, c.1780. It is said that the name ‘silhouette’ was taken from Étienne de Silhouette, an amateur artist who was also the French Controller-General of Finances under Louis XV. As a method of ridicule, the name was used to parody his management of finances after the Seven Years’ War, reduced spending and taxes. Hence, the method of cut paper shades being ‘cheap’ were called ‘silhouettes’, but the term was not commonly used until the early 19th century. This ring is an example of how the silhouette presented the immediacy of death to the wearer, without any other connection between life and death; it simply captured a moment. French fashion has been a modern pillar of style, with the Revolution creating a wide dispersal of fashions and the creation of new ones. In 1804, the Napoleon’s Empire was announced and luxury trades were renewed with vigour. Bijoutiers, who worked in ordinary materials and joailliers, who worked in precious stones benefitted from this rise in luxury, with Napoleon requesting the jewels from the former kings of France to be set in the Neoclassical style, essentially connecting him to the Greco-Roman empires. His coronation crown was decorated with cameos and his passions for the antique world led him to establish a school of gem engraving in 1805. If ever there was a height for the Neoclassical period, it was this connection to it. How other societies would reflect this moment is seen in their contention or support of Napoleon. Here is a person who is appropriating the classical world in a time where it had been in mainstream thought and fashion for around forty years. International tension would only lead to the decline of this style, as cultures needed to obtain their own identities in jewellery fashion. A great push to the Gothic Revival style in England has its roots in this.

By its very nature of wealth, jewellery was seen as a status symbol in France; an identifier for aristocratic status. During the Terror, the very possession of jewels or belt buckles may be enough to condemn one to the guillotine, while those who gave their jewels to the cause were seen as supporters and others simply hid theirs away for financial security if fleeing the country.

Jewels that were sold off following the Terror flooded the European market and dropped the prices of gems. In Paris, the only jewels to remain popular were souvenirs of the Terror itself. Simple iron relics inscribed with commemorations about the storming of the Bastille, or pieces containing stone or metal from the Bastille. Jewellery, by essence is a token. A reminder for memory to signify a time or a relationship in time that others can identify you by. When a culture suffers such a dramatic change, the utilisation of jewellery to promote a political message is not only important for the person’s connection to a community, but for their very safety itself.

In 1797, the Paris Company of Goldsmiths was reinstated, after being abolished in 1791, reintroducing many of the goldsmiths from the reign of Louis XVI. By 1798, hallmarking was established in France, making it compulsory to stamp jewels under three standards of purity; 750, 840 and 920 parts per 1000. They were also stamped with a maker’s mark (the maker’s or sponsor’s initial) and symbol in a lozenge-shaped stamp.

Filigree jewellery and fine detail to gold work had its inception here, as there was as shortage of money and goldsmiths became inspired by French peasant jewellery to produce finely detailed gold with lesser materials. Seed pearls, basic gems (such as agates) were also popular, as seen in the previous seed pearl ring and the access to the Orient.

Fashion in the time of 1780s France is represented in this miniature through the immediate depiction of the parents in mourning. The gentleman is clutching his kerchief to his face and dressed in a style reminiscent of the above fashion plate from c.1780. The waistcoat, breeches, powdered wig and lace cravat are shown in high detail (something unique and very resonant of the quality within the miniature). Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow and urn here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

Post 1760, the Neoclassical movement had crept into the previously fashionable Rococo style of costume fabrics. Elaborate Rococo floral motifs moved to simple stripes or smaller motifs. Side hoops were discarded and lighter silks and cotton was introduced, with much influence being from the aristocracy. Marie Antoinette was painted in La reine en gaulle, by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 1783, introducing a new style that reflected the peasantry, showing a muslin chemise, straw hat and belt at the waist. Some of this style can be seen within the art of the miniature itself.

The 18th century welcomed in greater convention for mourning fashion and began to see the rise of the mourning industry. This became so much so that mourning dress was becoming desirable and the difference between mourning and non mourning dress was narrowing. Much of the fashion in this century was dictated by the fabric rather than the cut, and the silk industries in France and England held major influence on mourning wear because of this. It was Ordre Chronologique des Deuils de la Cour, (1765) where details of Court mourning in France were published, giving precise tailoring instructions. From their first days in mourning, men were permitted to appear in Court, unless it was after the death of a parent from whom they had received inheritance.

Widows had to wait one year and six weeks, with the first six months in black wool. Lord Chamberlain and Earl Marshall both ordered shorter periods of mourning in France and England respectively. Bombazine dresses trimmed in black crape, black silk hoods and plain white linen were worn with black shammy leather shoes, glove and crape fans. Jewellery was not permitted. Second mourning consisted of black dresses, trimmed with fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black or white shoes, fans and tippets and white necklaces and earrings as necessary. Grey lusterings, tabbies and damasks were acceptable for less formal occasions.

Ordre Chronologique des Deuils de la Cour was specific and influential enough to decide upon women’s fashions, as. It was specific enough to specify that; ‘dress was cut with a train and turned back with a braid attached to the side of the skirt, which was pulled through the pockets.’ This is where the overskirt is turned to the back and lifted up, revealing the petticoat underneath, called; robe retrousee dans les poche, the centre front robings were joined with hooks or ribbons. Cuffs were cut with one fold and deep hems, the waist was held in place by a crape belt that was tied on. This left two ends hanging down to the hem of the skirt.

A woman’s accessories were a crape shawl, gloves, shoes with metallic bronzed buckles, a black woollen muff and a black crape fan. Head dresses of black crape and white batiste were referenced. For much of the century, however, ‘paniers’ were fashionable, but in the French style, with loose pleating falling from the shoulders to the back. The English manner of this was with the back pleats stitched down as far as the waistline. Also popular were lace ruffles at the neck and the cuff, embroidered stomachers, silver gilt lace, appliqué work and small aprons. None of these were permitted for mourning wear. Mourning wear for women still remained consistent in that it remained plain, black or sometimes white fabric.

Grief

There is no doubting the level of individualisation that’s painted within the watercolour scenario of this ivory, gold and pearl miniature. As can be seen, the willow is depicted in heavy detail, along with the cypress in the background (pointing towards the heavens) and all colour is drained from the image, apart from the tomb itself. This is the focus of the jewel and this is why we are discussing it today. Francoise Antoinette Elizabeth Martin passed away on February 22nd, 1787 at the age of 11 and this piece respectfully captures the emotion of the family, while embruing it with the Neoclassical values of the time. It is a beautiful sentiment for one so young, but also a powerful statement for a family that needed to hold on to an object to remember their child.