Fatherly Love

Love of a father represents the paternal aspect of a family which had been seen as the provider and the flagstone of the family as a concept. When the father passes on, the family enters deepest mourning and this represents the values of a father. Understanding mourning custom for males and those in a family who lose a father is often taken for granted, as it is the female subject who wore the jewellery and became the symbol of mourning for a family.

Men were not excluded from the affectation of mourning, as their fashion adapted to respect the stages of mourning, but it was much more sedate. It is the stoic concept of the patriarch that resonates through much mourning culture, with outpourings of grief not the common theme of the male in mourning. Only from the Enlightenment was the male more aware of the identity of the self and allowed to present themselves in deep stages of mourning through jewellery, a theme that can be seen in the Neoclassical period of the post 1760s.

By the Victorian period, the ‘Christian family’ had been established. Many of our Western rituals that we still sustain today, such as Christmas, were established during this period, with much of this having to lend itself to Queen Victoria’s British stability during a time of unrest in Europe and in the United Kingdom. The tokens and affectations of sentimentality are built into social identity, so if a person was expected to present themselves in society in a particular way, then the industry surrounding it would produce the items it required.

Mourning, by 1832, was changing its perception and values in British society. Governments, particularly in times of political instability, can utilise a public mourning period to mass produce materials for a departed monarch, aristocrat or war hero. Jewels and peripheral items made for Princess Charlotte in 1817 led to a mass production of accessories and mourning items due to the massive public outpouring of emotion for her. Lord Horatio Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar denoted an important milestone in British history with the victory over Napoleon’s forces being symbolic. When a public event is referenced by a government, its significance is remembered, to the point where a memorial item might be replicated in future times to reignite the memory of the occasion and what it means for cultural unity and identity. Nelson’s mourning rings have been replicated on the anniversary of the battle and once more, the memory retains.

The 19th century was a period where the need to maintain a stable culture was paramount to survival. The Napoleonic Wars and change in society through the Industrial Revolution caused massive population increase in industrialised towns, which leant towards a larger issue for governments to face destabilisation. Larger populations in smaller areas could carry a message and lead to another Terror, so the investment in creating an identity was desperately needed.

While the Crown had not had the command it once had since the Reformation, as most of the decisions went to the parliament, resentment of George IV through the excessive spending on arts and the treatment of a popular figure such as his daughter, Charlotte, government needed to adhere to something which could stabilise a diverse kingdom. This was ushered in through the Gothic Revival period and its use of the Rococo styling that was can be seen in architecture (such as cornices) and furniture design. Its use, combining floral and acanthus motifs, are decorative and dominating, imposing a style which was opulent upon a society that was moving away from the excess of the Regency Era and towards the simpler pre-Enlightenment Christian values. Dominance in style is a reflection of the majesty of God and final judgement, where a life lived in piety would be rewarded with entrance into heaven.

Much of this thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

With the establishment of a style of mourning that could be popular, it needed industry to accommodate it. During the 19th century, rules became more convoluted. A mix of reasons led to this high level of detail, ranging from the value of the mourning industry and economics, through to social control in an unstable environment. Economically, there was a mourning industry that became a legitimate strength in its own right. Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crape gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act. £40,000 to £450,000 is a major leap in a short period of time and shows just how powerful the mourning industry had become. Economics also led to new materials and concurrent industries to link into the mourning industry through fashion and mandate. Jet is a good example of this, as in Sylvia’s Home Journal it was stated for a widow in the first year of mourning (1881) that ‘no ornaments except jet’ could be worn.

In jewellery, it only took innovation to deliver a higher output of jewels. This can be seen in the Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys in jewellery. Pinchbeck and other alloys are common in jewels which identified with the look of what mourning was trying to achieve. Cheaper jewellery that looked large, with the elaborate black enamel, could be worn in costumes that were becoming larger and more voluminous. Identity, driven by politics and delivered by industry is the surest way to sustain a population through visual control. Judging by the growth of these industries during the 19th century, this pendant from 1832 has a solid tale of its message to tell.

Style doesn’t require a catalyst. It is an evolution of understanding and concepts which can challenge ideas, but not fully require an entire population to change a look overnight. Age and identity mean that a style of a grandparent may be worn for the rest of their years and a contemporary look is fleeting. Mourning jewellery is adaptable in its style, but its message generally stays the same. This is why the style of jewellery is so important as to define a time or social change.

From the Neoclassical period, allegorical statements of love and death made their way into jewellery through depictions painted on ivory or vellum. In this case, it is recessed in gold through black and white enamel. What can be seen here is a literal representation of the body and decay, through the use of hair woven into the plinth, it is literally a piece of the loved one in a tomb. The willow which overhangs is the primary statement of mourning for jewels of the Neoclassical period.

Wearing a style of ring like this in the 19th century, from a male perspective, would replace the Neoclassical scenario on top with woven hair and, by the latter 19th century, place the hair underneath the ring. In the case of a lady, it would be prominent. Jewellery was not exclusive for females during the 19th century. Men, wearing monograms and bolder gems, would wear rings that denoted social relevance, the wedding ring being another prime example of this, which is still in practice today. Contemporary thought often leads the wearing of hair to be directly death, but a gentleman wearing a watch chain made of hair or a ring with a hairwork compartment was quite sentimental and typical.

Men’s costume in the 19th century evolved from the opulence of the 18th century to the armband. As discussed, women became the focal point for mourning and the household, men’s regulations were freed from their previous obligations. By the turn of the century, men removed all gilt buttons, buckles and Court swords and replaced them with black ones. Cloaks were worn to funerals, until they were replaced in the latter century with diagonal sashes in black or white crape. These cloaks were often only worn by the undertaker’s men post 1860, but had gone out of fashion by 1890. In a stark contrast to women’s mourning wear, only the black armband was necessary with a black suit. The black suit was not necessary for mourning, as the armband was representative enough.

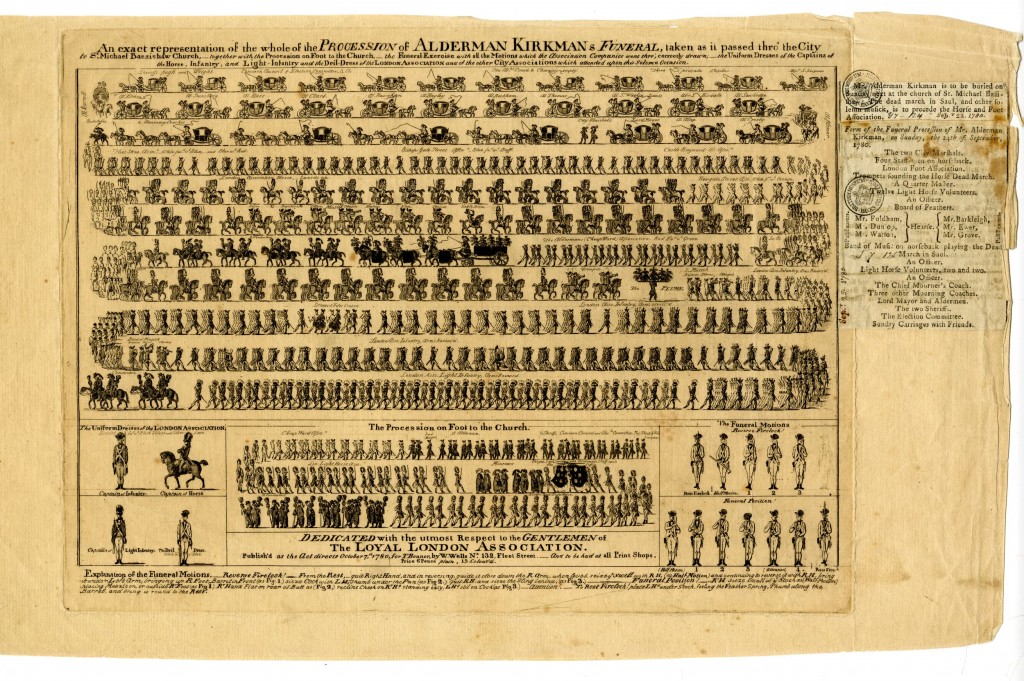

Men faced a difference in representation in mourning during the 19th century. From the above funeral procession through London, each row shows a different stage of the procession, from carriages to aldermen to infantry. Its detail shows all the elements of uniforms worn and what the funeral motions were. When relating this ceremony to the reflecting mourning male, the image becomes more striking. He is drawn at an individual moment of mourning that is quite private to be seen. This is at the stage of the funeral, and considering that the photograph seen earlier in this article is nearly a century apart, the ceremony has a similar narrative, but not the same grandeur. Men are used in the same capacity, but the fashion has changed greatly to bring together daily wear and the trappings of mourning.

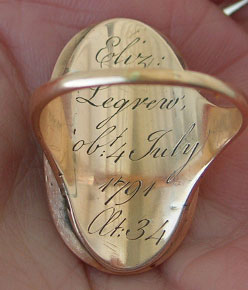

The male in mourning rings of the late 18th century and the Neoclassical period is a rare and important symbol, as it can tell us much about the jewel with which it is placed.

The woman, being the idealised romantic and symbolic centre of mourning for the family and the individual who would be wearing the jewels depicting grief, is the most standard mourning character of the time. Often wearing the white Neoclassical mourning attire, she is often standing or sitting next to a tomb or plinth, flanked with symbols of death and surrounded by the weeping willow. Often, these pieces were pre-created and sold with minor customisations to the person who acquired them, others, however, are of a higher quality and are purely commissioned for the person in mourning. These can be seen for their differences within the mourner herself; faces and costumes can often reflect the wearer and the jewel is almost a portrait, capturing the individual in a Neoclassical setting and depicting their grief.

While many miniature portraits of the time were created with a Neoclassical ideal and many facial features were standardised (eyes being an important one), the male in mourning depictions is too small within the jewel to standardise and not prolific enough to create many of, then sell them for a profit. The gentleman is often wearing the fashion of the day, the hairstyle would be that of the person who was wearing it and the more minute features would be accommodated by the miniaturist.

The scene of the gentleman beneath the willow and the plinth are designed in tandem. We have the larger willow hanging lower than many concurrent pieces (where the willow would flank the border of the ring) and notice the lettering of ‘WEEP NOT’ – it’s designed around the leg of the gentleman, rather than being intersected. The wider urn is on display here, slightly to the left of the centre of the plinth, putting the focus on the gentleman. This is important, as often the urn would be the centre of the piece, making the reason for its being the person who was passed, but this ring seems to put the emphasis on the gentleman himself. The gentleman, as well as wearing the piece to show his grief, is depicting himself within himself to be in mourning, which seems to deflect the focus away from the Elizabeth Legrew.

It’s interesting to note that the period of 1790 saw the height of the Neoclassical sepia and mourning depictions with the highest degree of variance. Location and fluctuating styles had much to do with the kind of a jewel that was produced for its time; you’ll note in mourning jewellery that the customs, visual preference and style can be completely different from city to city.