Family Bracelet: The Importance of the 1840s and 1850s Part 2

In the first part of this series on a remarkable bracelet, we discovered just how important the 1840s and 1850s were to modern culture. The weddings, funerals and jobs we go to were defined by the social establishments of those times.

As the impact of 1840s and 1850s culture led to nationalism and globalisation, the technologies developed during those times became the bedrock of how people travel and communicate. Jewellery and fashion needed to adapt to reflect this. Travellers and those who relocated around the planet needed to adapt to new climates, which led to anthropological fashion. Colder, warmer, humid and dry climates affected how people would dress, as well as how they would work.

Jewellery adapted along with these fashions and due to the Industrial Revolution and mass production, jewels could be made with one consistent style internationally. Souvenir jewels and tokens of love became instantly accessible. As more literature was published romanticising the practice of gift giving, as in the works of Charles Dickens or regularly printed periodicals, educated people copied the behaviour of gift giving.

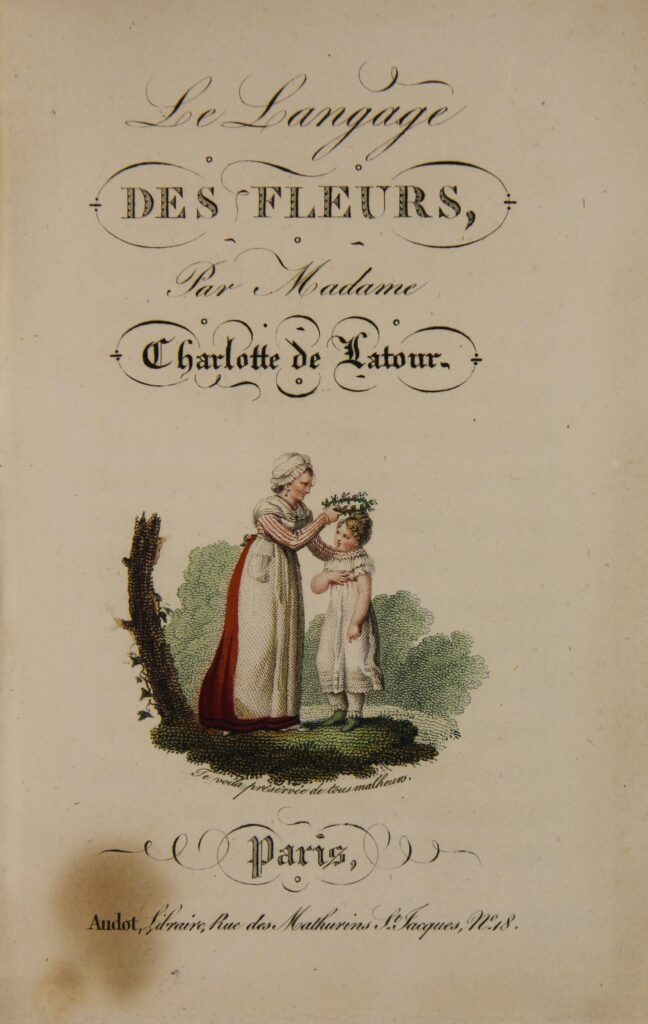

Floriography was popularised in Anna Christian Burke’s ‘The Illustrated Language of Flowers’ (1856), which documented the sentimental meaning of flowers for people to understand. Tokens of love and sentimentality flourished, they could be mass produced and the Victorians held dearly to these designs for their sentimental messages. Previous to this, Louise Cortambert, who was writing under the pseudonym of ‘Madame Charlotte de la Tour, wrote ‘Le Langage des Fleurs’, which has been attributed to being the first dictionary to identify the meaning of each flower.

The first transatlantic telegraph cable became operational in 1858, removing the barriers of communication between continents. In the same way that modern communications are instant and international, the 1850s was the first decade to implement this as something which would control modern daily life. Sharing international fashion through rapid transit and the ability to have a vacation, which was something a growing middle class could do, would bring back new styles into a population.

In 1850 the population of the United States was 23,191, 876 and an estimated 11,300 of these were ‘ocean-bound tourists’. The influx of international sharing and communications challenged design, but also allowed for societies to borrow from cultures that were deemed as the more established for their fashion, such as France and the United Kingdom. The crinoline was important for this time, as it was adapted internationally and accessorised jewellery also needed to adapt.

Hollow construction of c.1850s jewellery correlates with fashion change and a very important watermark in legislation; the 1854 Hallmarking Act. This act allowed for the use of lower grade alloys in jewellery, which is why we have materials, such as Pinchbeck (a blend of copper and zinc) being used to create many of the jewels from the 1854 onwards. In fashion, it was the crinoline, with is large, hooped skirts and the large, voluminous sleeves, being the reason for why jewellery needed to be larger and lighter.

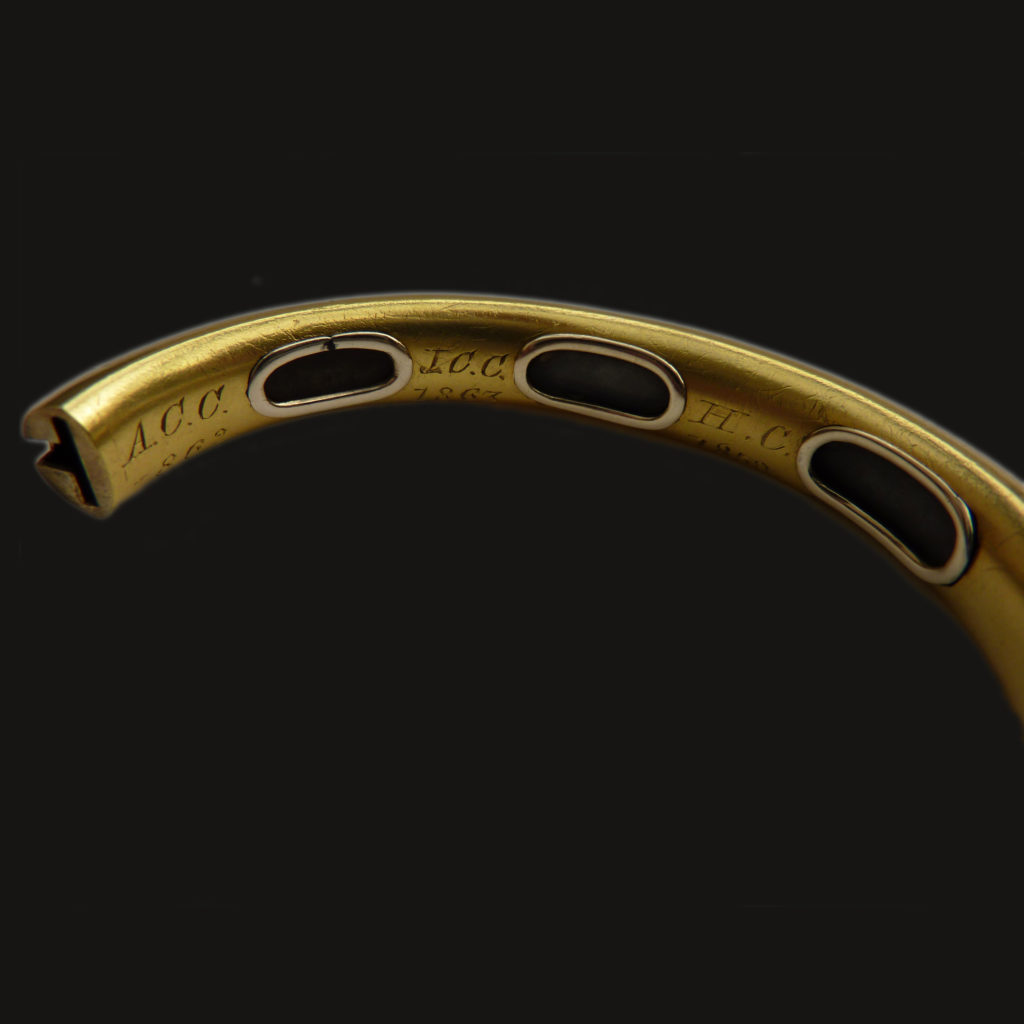

The bracelet that is the focus of this article is remarkable for its construction method and design. It is narrow, worn tightly at the wrist. It is of a high gold carat content and it features the most remarkable three compartments for the child’s hair to be placed inside bracelet. The bracelet is elegant with its use of the compartments, which align more to the geometric lines more familiar during Regency jewellery design. It is a remarkable sentiment in a time that was abundant in design elements for flowers and classical revival styles to be so simple and direct in its message. Considering that the bracelet was made with six direct compartments, the jeweller’s brief must have been very specific. This isn’t a jewel that would have appealed to a mass market, due to its specificity in design.

This bracelet covers off the following dates that correlate with the hair compartments:

- 1858

- 1859

- 1860

- 1861

- 1863

Which are quite broad dates, but were typical for jewels to have additional sentiments designed for them during this time. Today’s bracelet is more special in that it couldn’t be adapted over time.

In this silver bracelet, which was given to Queen Victoria in 1854, the portraits in the above segments between the double-winged putti show the children who were alive at the time. Princess Beatrice was not yet born, so her addition is in the suspended segment, which drops from the bracelet.

Gift giving and tokens of affection were now more accessible than any other time in early modern history. Alloy construction allowed for cheaper jewels to be produced at a higher volume, letting lower and middle classes have access to jewels that looked far superior. Jewels were produced internationally with the term ‘souvenir’, from Norway to South America. These jewels were produced for a multitude of reasons and in different qualities. Many souvenir jewels of this time followed a similar design language to the bracelet in this article. The clasp, which inserted into its counter housing relied on expanding to lock into place.

Jewels in this period followed this design during the mid 19th century. Souvenir jewels were particularly popular for the Great Exhibitions, where people of the middle classes could purchase cheaper jewels and wear them to the exhibition. Some were filled with plaster or wood to give them weight, which was not advertised by the retailers, but as a way of displaying wealth.

National souvenirs were especially popular, as well. The Australian goldfields in the state of Victoria in the mid 19th century produced many jewels with nationalistic Australia flora and fauna, with the combination of the pick axe and shovel to denote the miners.

In the following example, a souvenir jewel commemorates the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1871), which plunged France into depression. 15,000 square kilometres of territory was part of the war reparations given to Prussia and the nationalistic loss made jewellers focus on creating nationalistic souvenir jewels.

Two shields that bear the coat of arms of the Alsace-Lorraine region that was lost. Notice how they are divided, with the ivy representing temperance and the anchor for hope. Souvenir jewels still retain all the sentiment of a higher quality jewel, and in the case of the Australian goldfield’s jewels, could even be produced at a higher level of quality with the gold that was dug from the fields. This French piece is oxidised silver-plated metal, with plaques of enamelled gilt metal and stands out more in its design than its materials.

Gifts for travellers have been common throughout the early modern period, but now with the higher level of international travel, industries could exist on tourism money. This Swiss pendant and chain was likely created for British tourists, as it is possibly part of a Göllerketten (collar chains), which are unique to Switzerland and parts of southern Germany. Jewels that maintained a cultural design were popular trinkets to take back home when travelling, something that had always been popular in areas linked to ancient Mediterranean cultures, but now smaller cottage industries represented local culture.

One challenge to sentimental jewel gift giving was the advent of the photograph. As photography became cheaper and more accessible, its uptake into society forced sentimental jewels to adapt and grow with them. Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre popularised his patented photographic technology through being a talented promoter. Having a history in commercial art and theatre production, Daguerre received a French government grant for a pension to be recognised as the inventor of this technology. The popularity of the daguerreotype led to over 70 photographic studios in New York City in 1850, a massively rapid uptake since its inception in 1839. As such, the daguerrotype reigned as the most popular photographic technology, until ambrotypes took the market lead, due to their being less expensive and easier to produce. By the 1860s, daguerrotypes were considered obsolete.

This bracelet houses 13 sepia portrait photographs behind convex glass. On the reverse is the word and date ‘SOUVENIR 1868’. Souvenir jewellery, photography and a very high quality piece are all in one. There’s a lot of balance between the bracelet that is the object of this article and this particular bracelet. Where the hair was used in 6 compartments in that jewel, this one uses photography in the same way. Their sentiment is no different, however, but it would be interesting to see how people of the day reacted to one or the other. This bracelet is part of the Royal Collection, so it was gifted to the Royal family at some stage of its life.

In such a simple bracelet, there is so much context. The 1840s and 1850s are an inexhaustible wealth of cultural history that is tied to modern times and this bracelet shows that, right down to the integration of the names, which speak to family values. It is for this very reason that humans connected through all the technologies and systems of the mid 19th century; to create communities. Nationalistic pride took the forms of new wealth, the Great Exhibitions took pride in displaying the various levels of invention and quality that a nation could provide, communication became global and rapid transit took people to their destinations faster.

Every time you appreciate a jewel, consider its context and how something so small can open a door to an earlier time, when we were no different than today.

Bracelet courtesy Animal Antique Jewelry