Family Bracelet: The Importance of the 1840s and 1850s Part 1

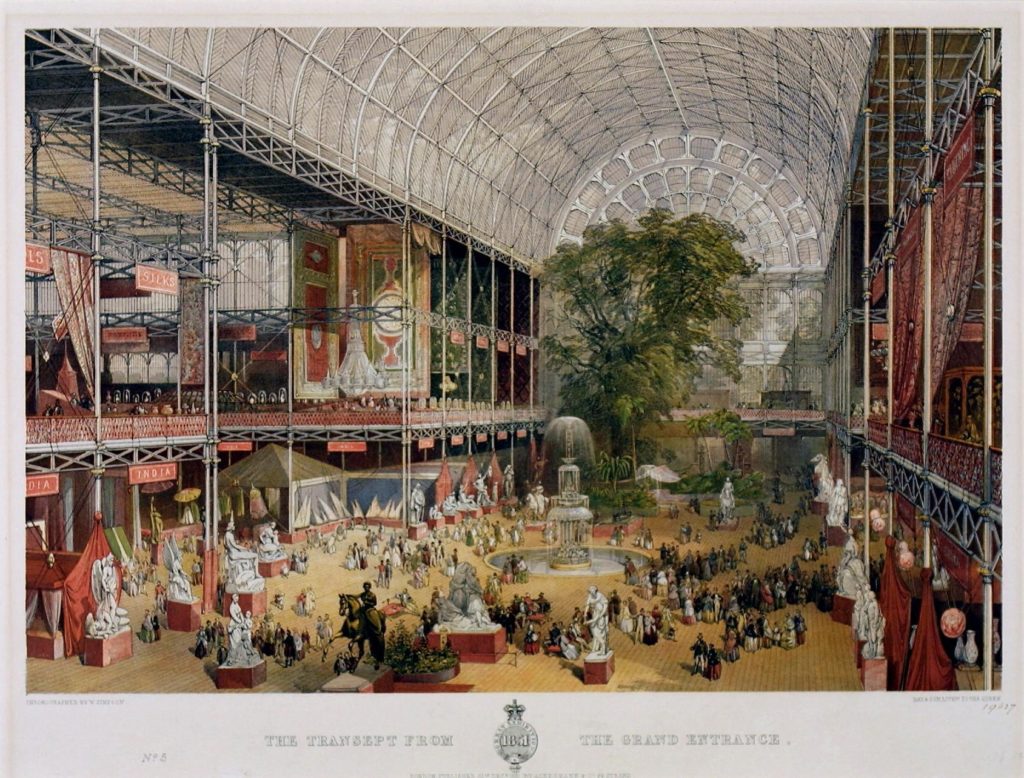

In terms of human identity and the roots of western modern culture, the 1850 period was the most important decade to establish social behaviour. From technology and its showcasing in the Great Exhibition of 1851, to the parameters of social behaviour for families and how that was popularised by the British Monarchy and seeded through popular culture by authors such as Charles Dickens, it was a time of colonisation and international representation.

Jewellery and fashion are interlinked to the DNA of society, as how people dress represents the culture in which they live. From the importance of a wedding or a mourning ring, to the colour of a dress; these values represent a family, religion and how one should behave in a society.

There is no one catalyst in history, but a series of evolving events that establish these things. Previous to the 1850 period, the 1840s were very destabilised, with a cascading wave of revolutions in 1848 that began in France and moved across the German Confederation, the Netherlands and provided a platform for Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to write the Manifesto of the Communist Party. It was the working class and their exploitation in the businesses of the Industrial Revolution that led to a wave of dissatisfaction. Urbanisation helped fuel their voice, as people moved from an agrarian communities into cities.

Rural areas also became more populated and this led to an 1840s famine, with society taking an even greater burden due to the 1846 potato blight. Poor treatment, unregulated industry and famine made politics and the upper classes face a series of events that hadn’t occurred since the c.1780s. Consider that this had happened once in the lifetime of a person, hence it was still fresh in the mind of those who had lived through it.

The 1850s were not without their challenges. The Crimean War (1854-56) was fought between the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire and Russia. In 1857, the Indian Mutiny was a revolt against British colonial rule and Bleeding Kansas saw the results of America’s feelings towards slavery, as a series of confrontations between 1854 and 1861 led to two separate governments in Kansas – one pro slavery, the other against.

Something needed to be done to reaffirm the status of the British Monarchy and what it was to be a member of the British Empire. Between the 1st of May to the 15th of October, the Great Exhibition of all Works of Industry of all Nations was an initiative led by Prince Albert, consort to Queen Victoria. It championed the role of Britain as the leader of modern industry in the world, sparking a high level of nationalism throughout society.

Coinciding with this was the Ballarat Gold Rush in the colony of Victoria, Australia, which led to a massive spark of international interest in relocating to the state for instant wealth. Within ten years, Melbourne, the capital of the colony, grew from 75,000 people to over 500,000.

Nationalism is incredibly important to the solidarity within a culture. It establishes the behaviours and social expectations of how a family behaves. At this time, the Gothic Revival art movement hit its peak in the 1840s, a style championed by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, an architect, designer and English Catholic who influenced jewellery and art design to revive the ‘Gothic’ period of style. This style was a push back into a different time, where people were under the eyes of god and judged when they died for permission to enter heaven. It was a style that dominated and made people feel that living a simpler, pious life was important. This was important for families, as well. Consider the design of a Gothic Cathedral and the flying buttresses, gargoyles, height and sharp lines. If one were to also think about the massive Industrial Revolution happening concurrently and the urbanisation that was occurring, it is plain to see how one is designed to counteract the other. Work harder and simpler, then be judged when you die to enter heaven.

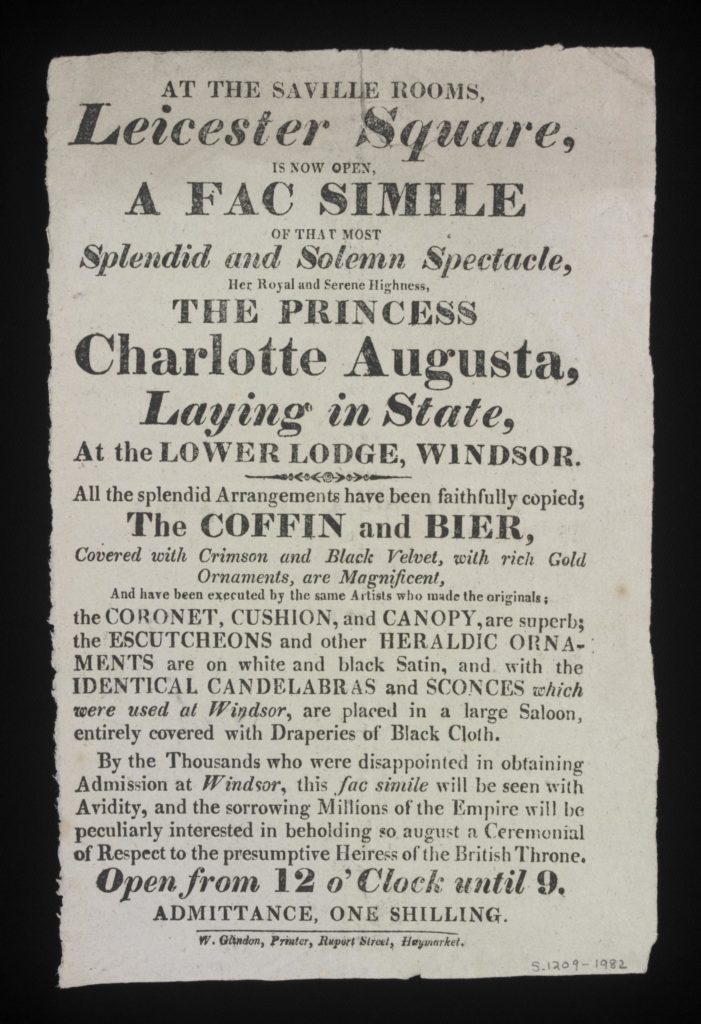

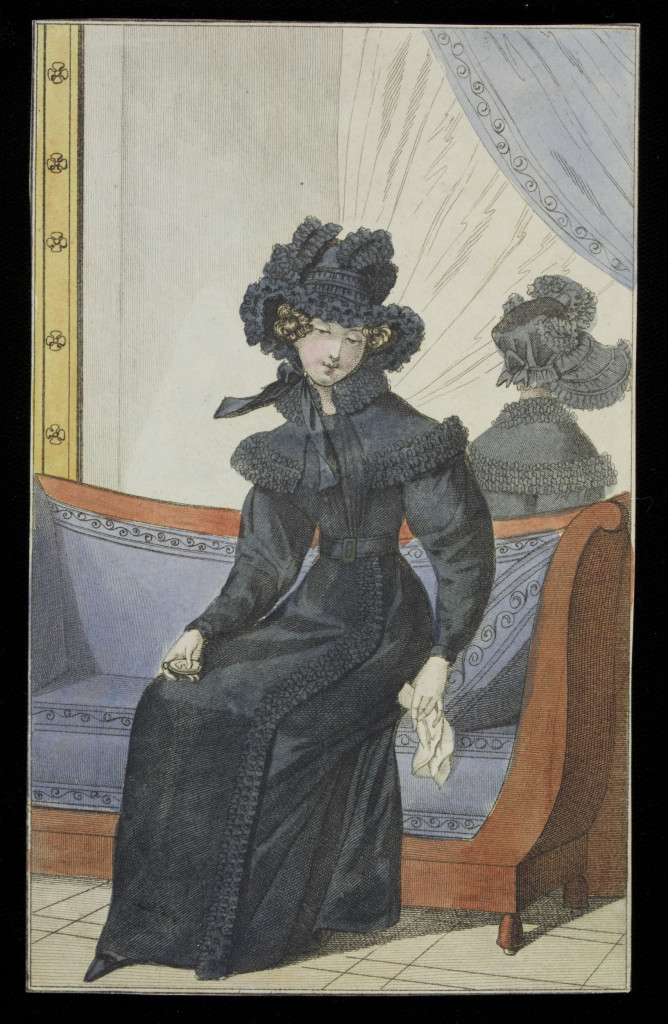

In 1829, the Catholic Emancipation Act allowed for Catholics to sit in Parliament, but the Church of England was, and is, the predominant church, with the Supreme Governor being the monarch. This has been the case since Henry VIII, but that does not mean a Catholic design could not be the main influencer of style for the 1840s. Jewellery design accommodated this well, as mourning jewels were displayed at the neck, wrist and fingers, mostly stating the bold, black enamel and ‘IN MEMORY OF’ sentiment. Where someone walked and was in grief, they were advertising the death values of the British culture and this was established behaviour. Since the death of Princess Charlotte of Wales in childbirth in 1817, the Lord Chamberlain rewrote the expectation for court mourning that would be adapted through 19th century fashion.

Mourning regulation went through different permeations in the 19th century and became longer and more rigid. It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning:

‘…the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crape hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crape fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crape hatbands and black swords and buckles.’

For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear. Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

Regulation of fashion, globalisation, mass production and industrialisation led to the 1850s being the consistent way that modern western culture behaves. From the happenings of the 1840s, such as Queen Victoria wearing a white dress to her wedding, we have the white wedding being popularised in the 1850s. Demand for Charles Dickens during the 1850s was high, as his serialised formula for publication disseminated ‘behaviours’ of the wealthy and poor to a massive audience internationally. Established behaviours in wearing mourning jewels and the stages of mourning were taken from the previous generation of the c.1817 period down to the new generation, who spread these customs out across the world. In 1861, Prince Albert would pass away and Victoria’s perpetual mourning popularised mourning fashion in court and in public, but the groundwork for this was already established in 1850s culture.

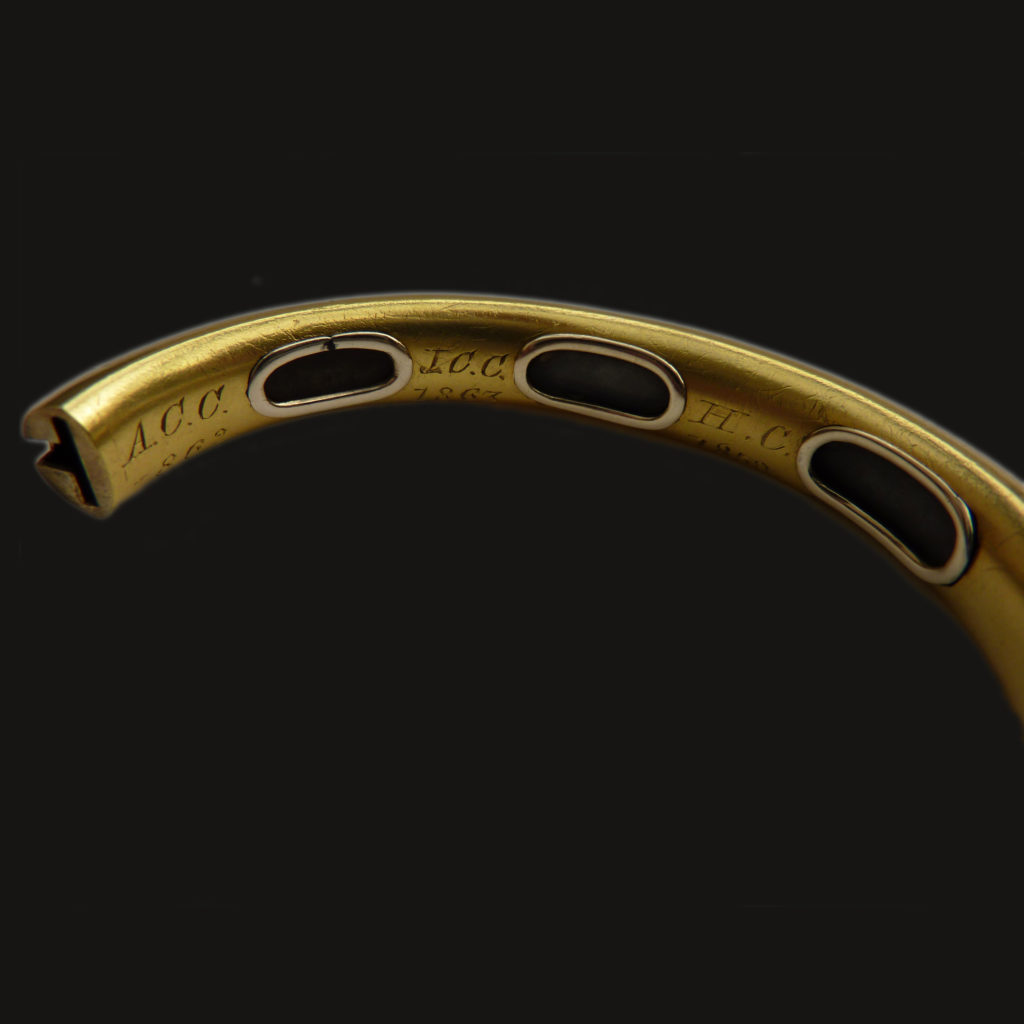

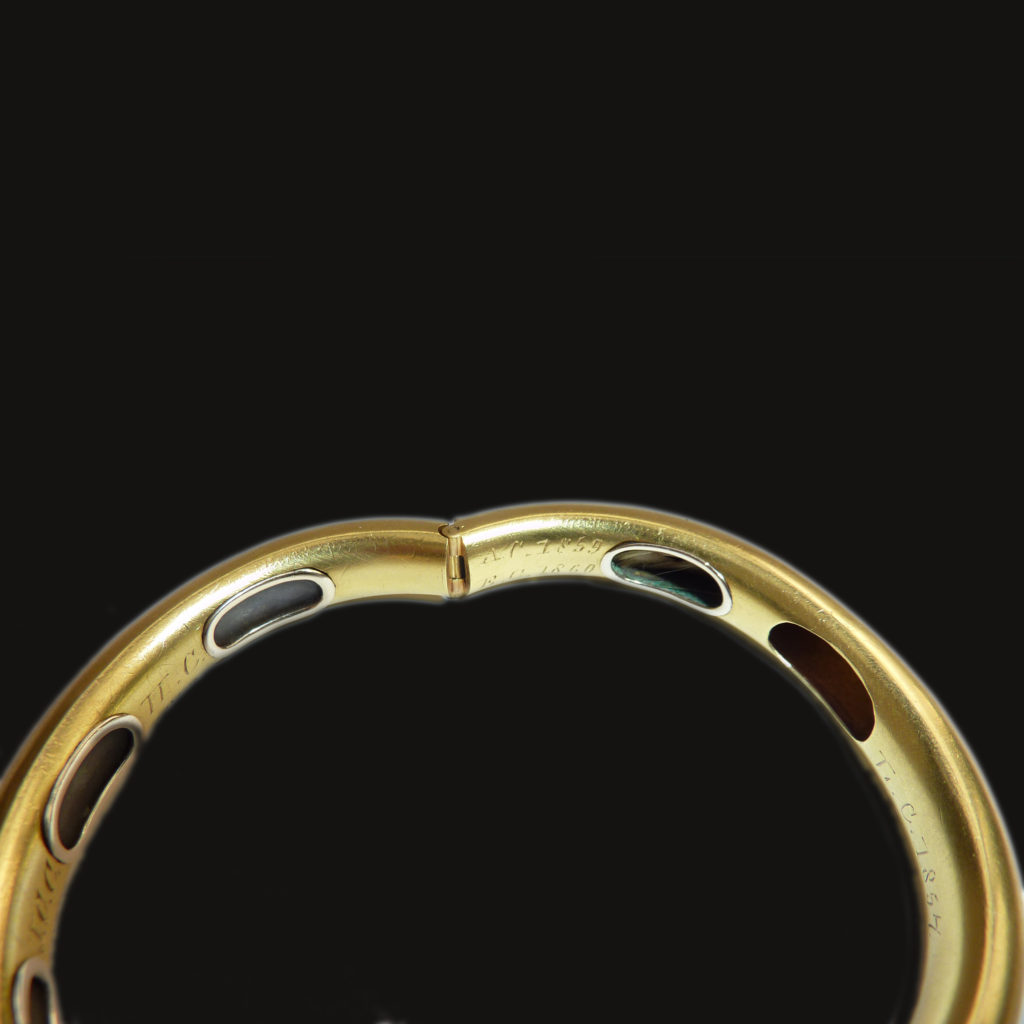

In the next part of our discovery of the 1840s and 1850s, we will travel into the design of this bracelet and why all the elements of its history created a remarkable piece of historical sentimental jewellery.