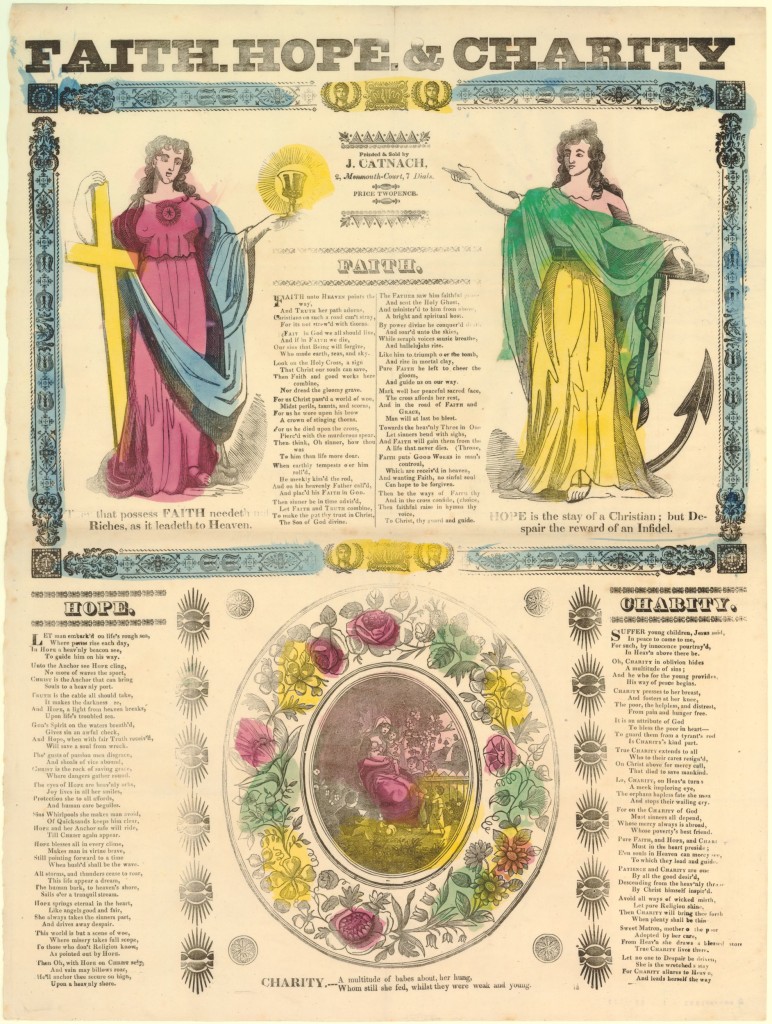

Faith, Hope and Charity

The allegory of faith, hope and charity are important symbols of the early modern period, becoming prominent from the late 18th century and still utilised today in jewels. Theology is one of the primary reasons for the creation of mourning and sentimental jewels, being a key identifier in someone’s understanding of the afterlife and their relationship virtues. In modern times, this has been disrupted through the questioning of faith under a system which did not honour the rules of the Bible, leading to a Protestant Reformation, which moved thought towards an understanding of the ‘self’ under god, rather than hierarchical devotion in practiced values.

Through the Enlightenment and the changing nature of industry and social mobility, regardless of faith under a ruler, the nature of Christianity still remained the fundamental connection in Europe. What is important during the post 1760 period is the Neoclassical movement. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the identity of death. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought.

Faith, hope and charity existed during these times, adapting to the modern fashion, and hence, remaining fashionable. Symbols became more streamlined and simple. Typically, these motifs were used and given in charms as a token of love and remembrance.

Hand-coloured woodcut and letterpress, 1800-1841

Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this Industrial Revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels.

Showing just how the 19th century marked a move back to the traditions of the Christian family, the ring above shows all the elements of pious faith, hope and charity symbols in situ. Jesus is shown in detail upon the front bezel, crucified. The allegory has changed, giving way to a true depiction of the suffering of Christ.

As attributed to the Apostle Paul, this quote from 1 Corinthians 13 shows the genesis of faith, hope and charity:

“And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.”

There is also the allusion to the holy trinity with the faith, hope and charity symbols, which links to another symbolism that is somewhat related. Not related, but important for the reason of its symbolism, there are two groups of martyred Christian Saints named ‘Faith’, ‘Hope’ and ‘Charity’ (love), denoting the three Christian virtues found in 1 Corinthians 13:13.

What is important is that these symbols blurred the line between allegory in the vision of a physical character representing them, or the basic symbols of what we identify as the cross, the heart and the anchor.

Faith

Representing the cross is faith, the belief in god, obedience and His revelation. The cross often stands taller than the other symbols when depicted in Neoclassical jewels, making use of the oval/navette shapes of the time. Faith and the cross symbol are generally hard to separate, even when the cross is used on its own, as it has the obvious connection to Christ. The cross had a renewed popularity in the 19th century as a symbol in jewellery, whereas its incorporation into Neoclassical pieces is often a little more covert. The Neoclassical period (in its basic form) was a revival of Greek/Roman/Early Western culture and art and it goes without saying that these were polytheistic societies. With greater social mobility, a shift away from the ecclesiastical lifestyle and putting more focus on the ‘self’, the use of heavy Christian symbolism was alluded to, relegated to peripheral symbols or painted at the request of person who commissioned the piece. This changed in the 19th century, with the re-establishment of Christian values and the cross became popular once more as a singular motif.

Faith is also the certainly that confidence brings in knowing that the reliance in faith is the strength to complete a larger task. Having the power of a deity to provide faith in that you and your loved ones will arrive at a higher existence of being is the ultimate security in religion. In the above pendant, the Victorian symbols of faith, hope and charity have come together in harmony. This is the style which characterises the identification of the symbols today, as is with most Victorian standard symbols. The anchor and the cross are perfectly unified in this pendant, with the heart being placed on top. Through this heart on top of the other symbols, the human quality shine through. Later in the article, the allegorical female will be seen in earlier jewels, but it is the heart which is human.

Hope

Hope, the anchor, can often be seen when combined with the cross to create the crux dissimulata (representing the church), but it lends itself to a more literal translation of the obvious anchor, meaning hope. During the Napoleonic wars, many of the mourning and sentimental jewels show the female with the faith, hope and charity symbols and the ship moving into the horizon. It was a relevant popular symbol at a time when seafaring meant that a loved one may never be seen again. Many times people can be confused with the anchor, it is also seen on its own and some see that as simply a seafaring relationship. When it comes to mourning and sentimentality, hope is a powerful statement on its own merits.

In the faith, hope and charity ring with the literal depiction of Jesus being crucified, the etched anchor can be seen in the amethyst. The anchor to moor the ship gives solace and comfort to the wayward ship, as it finds a home. Hope is fundamental to the principals of what it is to believe in a better future.

Flying the Union Jack flag, this print from 1797 shows ‘Hope’ as an allegorical female figure, shown full-length standing on a sea-shore, leaning on an anchor and gesturing out to right, a spotted scarf looped around her, from a set of Faith, Hope and Charity.

This print was created in 1798 and reads:

‘Bless’d Hope will surely lend her Aid, / When most of comfort we’re afraid, // Do not despair Tho’ World’s may frown, / For Virtue shall with Joys be Crown’d.’ and ‘Design’d by // B.t Reading. // Published July 16th,, 1798 by P & J. Gally, No,, 3 Leather Lane, Holborn, London.’

Hope for the loved one to return safely home is essentially the personal sentiment that the symbol can relate to. At a time when danger was typical for travel and Europe was in conflict, the hope that a loved one could apply towards another was the basic human connection.

Introducing the classically dressed female into the symbolism brings it into the contemporary times of the late 18th century. The female would often be the symbolic focus of sentimental and memorial art, being the representation of the ‘self’ in the piece, and here is a perfect depiction of how the lady leaning against the symbol treats religion with humanity.

Dating from March, 1788, this brooch for Sarah Honlett was created for the purposes of mourning. She was aged 14. As in the 1798 print, the figure is integrating with the symbolism, but here, the cross is designed more into the anchor itself. The lady is pointing upwards towards the heavens, denoting death and flanked by the willow. Be it the willow or the sea and the ship, the balance of mourning/sentimental symbols with faith, hope and charity are constantly the addition to the personal religious sentiment of virtue.

Utilising the female character brings humanity back into a very ecclesiastical sentiment. As the prints in this article have shown, the female character can represent a person or state, but its identity connects other symbols together.

As can be seen in the costume of the allegorical female ‘Hope’, she is prepared for a confrontation, which is unsurprising during a time of the War of the Second Coalition, where Britain, Austria, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Naples and Portugal attempted to contain the growing republican France. Having faith would be a benefit to the person who wore the symbol, understanding mortality and how strength through belief in a god or monarchy would be a mark of solidarity.

Faith and hope are the common personifications of the symbols. The below bracelet clasps by Sir Joshua Reynolds show the two figures in detail:

Hope, with her arms outstretched is at the mercy of fate, longing for the elements and the heavens to deliver her prayers. Faith is shown with direct piety towards the heavens, with the cross clearly seen behind her. As these clasps fit into the Neoclassical period, they show the classical figure in costume, with high definition to the layering of the fabric on the figure. The reality of how these artistic pieces could be viewed in society deliver that human connection of emotion first. A strong message of piety which reverberates through to the message of faith and hope and what their definition meant in the ecclesiastical sense.

Charity

Charity is represented by the heart, which is often depicted as burning, seen in the jewel above. Charity/love are represented by the heart, which is a derivative of ἀγάπη (agapē), the world used by the English translation of the Bible in the 16th century. It was only in the Challoner Douay Rheims Bible of 1752 and the King James Version of 1611 that the term ‘charity’ was used for the similar ideal of Christian love. The heart is one of the most commonly used symbols in Western society and also one of the most timeless. Charity is love and affection and you will no doubt see this symbol a lot on your travels. Defying any strict religious connotation, the heart motif has transcended nearly all of the evolving art styles upon sentimental jewellery. These pieces were created with the intention of love, so what is love without a heart? The development of the heart will be discussed further in the article, but it is important to see how the nature of ‘charity’ could be seen as a physical being.

Suckling and carrying her young, giving nourishment and smiling beneficently down upon her young, the allegorical female figure is flanked with the emotional symbols of nature in flora. As stated, love and affection through charity is the Christian way of showing benign love, rather than that of a physical passion, which would be seen in other more sentimental loving jewels of the time. The heart, however, is a burning one; one that longs for another and burns throughout eternity.

During the 19th century, the sentiment remained unchanged. Love is the concept which only grew in a deeply symbolic way through the 19th century, particularly in the heart.

Note the etched burning heart in the faith, hope and charity ring, depicting the figure of Jesus. Its style hadn’t changed, meaning that by the 19th century, the symbol of the heart was well and truly identifiable and represented love in the manner that it does today.

When the heart was worn for a loved one who was alive, it was a symbol of betrothal, marriage or love and affection, or if dead, grief for the departed. With the rise of cupid in sentimental jewels, the heart was a popular motif from the 17th to 19th century, but one which obviously resonates just as strongly today, as the production of heart-shaped pendants and lockets is still a popular design in jewellery. The heart has its origins in jewellery from the 15th century, but was enhanced in the 17th through the Enlightenment and the reflections of the humanist movement, but could also be appropriated for religious undertones when necessary. It is important to note that the heart shape which we understand today is still reflected in these jewels with the broad element of the shape. Upon viewing, the north of the pendant doesn’t have the sharp dovetail into the centre of the pendant, but rather curves around itself.

The familiar shape is seen at the south of the pendant, with the edges coming to the familiar shape of the heart that we recognise today. Elements of the heart shape had been perfected by the early 17th century, but the adaptation of the shape was common for sentimental jewels through the 18th and early 19th century, due to many other factors of the design flanking the shape and adding to its form. As written about extensively at Art of Mourning, the heart is one of the most important sentimental love symbols in early-modern history. Its obvious symbolism resonates today in tokens of love and affection, moving beyond religious and social values to be the most purely recognised understanding of love. With an anthropomorphic design, the heart symbol became popular in the 17th century with its romantic undertones of giving ‘your’ heart to another.

As earlier discussed, the heart is human. With other symbols that remain mysterious in their intent, from the anchor to the cross without the context of their meaning, the heart is a literal representation of our own anatomy. Used in symbolic jewels and still popular today, a heart is the empathic love that can be shared with others, meaning that charity is the one element to bring together faith and hope. Without the heart, one cannot have these or share oneself with another.

Faith, Hope and Charity Every Day

By the second half of the 19th century, the symbols had become standard and common charms to wear between men and women. There was no need to wear the symbols balanced with a female allegory; they could be given as independent symbols in the heart, cross or anchor as small tokens of affection.

A typical chatelaine or fob chain could house several charms, as well as items of daily use. This has four gold chain strands, each holding a 9 carat gold charm – a dog clip fastener, a horseshoe charm, an anchor, cross & heart shaped fob (faith, hope and charity), a hand carved translucent agate cross charm and a Breguet type watch key fob. Daily items which have regular purpose, yet the small love token appears as a personal sentiment of love.

Construction of the interlocking cross and anchor in this charm show the simplicity that its design could bring to a simple love token. It doesn’t need to be constructed from pure gold to be a love token, but something passed between loved ones to remind them of an occasion. Being worn in this way does not take away from the sentimental nature of the faith, hope and charity symbols, but makes them more common in the mindset of Victorian society.

Many of these charms are still produced and given today, but worn as pendants or more practical modern jewels. The symbols may have simplified, but they remain popular in Western culture.

Christianity is the basis for the early modern jewellery of mourning and sentimentality because these are the societies that have created modern Western values. Without being explicit, a symbol can mean many things, as well as being an appealing visual. When several symbols come together, their sentiment can amplify, particularly at times when the symbols aren’t readily identifiable. Be it for the purposes of fortitude, long life, hope or giving; faith, hope and charity remain popular symbols together or apart, regardless of their basis.